Efficacy of Continuing Advocacy in Involuntary Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The effectiveness of an experimental model of personal advocacy for involuntarily hospitalized psychiatric patients was examined. In the model, a personal advocate represented the needs and best interests of patients throughout the period of involuntary hospital treatment. METHODS: The sample consisted of 105 involuntarily hospitalized psychiatric inpatients in Canberra, Australia. Fifty-three consecutive patients received personal advocacy, which started soon after they entered the hospital and lasted through the commitment process to the time of discharge from involuntary care. The outcome of this group was compared with that of 52 consecutive patients in a control group who received routine rights advocacy from hospital entry through the commitment hearing only. RESULTS: The experimental and control groups were similar in demographic characteristics, diagnosis, and severity of illness. At the start of hospital care, satisfaction with care was similar in both groups; however, it improved significantly in the experimental group while it declined in the control group. Aftercare attendance was significantly better in the experimental group. The experimental subjects' risk of involuntary rehospitalization was less than half the risk of control subjects, and community tenure was significantly increased. Clinical staff reported that the experimental advocacy facilitated management of patients. CONCLUSIONS: Compared with routine rights advocacy, the experimental advocacy based on patients' needs and best interests, which was maintained throughout the patients' involuntary hospitalization, significantly improved patients' and staff members' experience of involuntary treatment. Better compliance with aftercare among patients receiving personal advocacy led to a statistically and economically significant reduction in rehospitalization.

Involuntary hospitalization and coerced treatment is a frightening experience even when a patient can see the benefits later (1). Coercion and the derogation of autonomy leave many patients unwilling to accept the follow-up treatment and services that may prevent their relapse and rehospitalization (2,3).

The impact of coercion seems to be mitigated if patients feel "respectfully included in a fair decision-making process" (4) and their autonomy is respected as far as possible (5). Patients feel unfairly coerced when they believe that their interests have been ignored. Clinical staff may underestimate the importance that patients place on inclusion in treatment planning (6) and the degree to which the reaction against coercion affects treatment and outcome (7,8,9). Generating and maintaining a cooperative clinical relationship will be difficult for services that provide coerced treatment because they may have to override patients' objections. In that situation it is rare that the treatment provided preserves patients' sense of autonomy and of inclusion in treatment planning, which may strengthen a therapeutic alliance (10).

In many Western countries, careful commitment processes have been built around involuntary hospitalization. These processes have ensured procedural justice when patients are admitted to a hospital. This approach may soften the impact of coercion and communicate the respect that fosters continuing cooperation with treatment.

However, in most Australian jurisdictions, advocacy and rights protections cluster around the point of hospital admission and rarely continue for the course of hospitalization, even though commitment licenses the hospital to repeatedly coerce patients during the hospital stay. Generally, there is no mechanism to ensure that respectful inclusion in decision making continues throughout the period of coercion. Equally important, usually no mechanism is in place to ensure that patients' needs are recognized when the treating team does not see these needs (11). Unlike voluntary patients, who are generally free and able to speak out, involuntary patients are often silenced by their illness and their status. Unassertive patients or the many patients who have no idea of their rights will not gain access to advocacy programs that only react to complaints (10).

The study reported here examined the efficacy of a particular experimental model of personal advocacy. In the model, an advocate joins the patient at the gateway to commitment and accompanies the patient throughout the period of compulsory care. Use of such an advocate was designed to supplement the usual advocacy and legal representation of the patient, which routinely occurs at the point of commitment. The study measured the effect of personal advocacy on patients' and hospital staff members' experience of hospitalization, on patients' cooperation with aftercare, and on patients' community tenure after discharge.

Methods

The advocate's experimental role

The advocate filled a carefully described role that had elements of conservatorship as well as advocacy. At the time of the study, the advocate was a woman. She was not part of the treating team and was employed by the local Office of the Community Advocate, an independent government body with rights and powers to represent citizens' interests in legal and administrative decisions of government. The advocate reported to a board independent of the hospital.

The advocate represented the patient's individual interests and was asked to attempt to create the "dialectic" or negotiation of consent between an involuntary patient and a treating clinician as would occur between a voluntary patient and a clinician. The advocate acted as the patient's voice in the negotiation of treatment. Thus she sought treatment options from clinicians and voiced the patient's current preferences or reported the patient's previous experience of treatments. The advocate pointed out particular needs or problems that may not have been addressed. She also watched for unnecessary infringements on the patient's autonomy.

The advocate was responsible only for the patient's best interest and not the best interest of the public, the state, or the hospital. When patients were mute or made demands that were clearly not in their best interest, the advocate was required to come to some understanding of patients' contexts and values to guide her own best judgment of what patients would choose if they were able to perceive their own best interest.

The advocate was not a friend who represented the patient's wishes and was not responsible for delivering treatment, which was provided by the clinical staff. The advocate was responsible for negotiating about treatment and for establishing a continuing representation throughout the period of compulsory care.

The advocate saw the patient at least every other day and sat in on case discussions with and without the patient present. When a patient resisted medication that was clearly necessary and in the patient's best interest, the advocate would not argue against treatment but put forward the reasons for the patient's objections, report the patient's previous experience, and try to negotiate a treatment regimen acceptable to the patient. The advocate would clearly indicate to the patient why she had not argued against treatment so the patient would know the treatment had been negotiated rather than simply enforced.

The advocate

The advocate was recruited in 1996 by a public advertisement that described the position as a time-limited research position. The position was well paid within the pay scales of the Australian Public Service. We were able to select an advocate (the third author) who was a qualified lawyer with a background in health policy and who had knowledge and skills that would otherwise had to have been taught to an advocate.

Advocacy procedures at commitment for all patients

Most involuntary subjects are admitted urgently. The local mental health law allows up to 72 hours of involuntary emergency care and treatment, during which time the circumstances of the admission are examined by a member of the Mental Health Tribunal, the body responsible for the administration of the mental health law. The tribunal member may confirm the continuation of involuntary hospitalization and treatment and schedule a commitment hearing by the three-member tribunal within the subsequent seven days. For the hearing, the patient is attended by an advocate who is not a lawyer from the Office of the Community Advocate and may request free representation by an attorney, although this request is rarely made. This routine advocacy is seen to play a "watchdog" role over the procedures of the state in detaining the patient and does not continue after the hearing. Further advocacy is available only if the patient requests it.

Setting

The Canberra Hospital is the principal hospital in Canberra, the capital city of Australia. It is a city of 300,000 people in an independent administrative region, the Australian Capital Territory, which has its own legislature and administration. The city has the highest average income and education of any state in Australia. The Canberra Hospital is the only hospital in Canberra authorized to receive, hold, and treat involuntary patients. The nearest such hospital is approximately 100 kilometers away in an adjoining state. On average, about 500 people annually account for 800 hospitalizations in the 32-bed psychiatric unit. Usually, at least one of the patients on the unit has been involuntarily committed. During the study period, no more than four involuntary patients were on the unit at any given time.

Subjects

Subjects were included in the study if they were admitted involuntarily, their detention was confirmed by a tribunal member, and they consented to take part. When hospital staff judged a patient incompetent to provide informed consent, the patient's consent was considered by the tribunal member who confirmed detention.

Between October 1996 and July 1997, a total of 105 consecutive individual patients completed the study as control or experimental subjects. Twelve potential control subjects and four potential experimental subjects declined to participate. Sixteen subjects (nine control subjects and seven experimental subjects) withdrew in the course of the study. Twenty-two subjects (14 control subjects and eight experimental subjects) were not reenrolled when they were readmitted to the hospital within the study recruitment period.

Study procedure

Consecutive subjects were assigned first to the control group until the requisite number of 50 for the group was exceeded. Next subjects were assigned to the experimental group until there were more than 50 in that group. The control group received routine advocacy, as described above, which consisted of representation by an advocate from the time of confirmation of involuntary admission (within 72 hours of urgent involuntary admission) to the formal commitment hearing (usually within seven days). Further advocacy was available during hospitalization only if the patient requested it.

The experimental group received the same routine advocacy and representation; however, from the time of confirmation of involuntary status, they also received personal advocacy from the specialist advocate. The personal advocacy continued actively up to the time of discharge from involuntary treatment, which usually coincided with hospital discharge; however, some patients stayed in the hospital as voluntary patients.

The study followed an A-B-A-B (control-experimental-control-experimental) design. Combining patients who had different advocacy regimens in the same hospital unit was neither feasible nor reasonable. Thus the control and experimental groups were hospitalized consecutively, not simultaneously. We used an A-B-A-B design rather than A-B to reduce the influence of nonrandom effects, such as seasonal effects; to equalize the duration of follow-up; and to reduce the tendency for frequently hospitalized subjects to fall into one group.

All consenting control and experimental subjects completed the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) within three days of admission. At the same time, one of several trained hospital nursing staff completed the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) for each patient so that the severity of illness of patients in the control and experimental groups could be compared. At the time of discharge, staff reported the impact of advocacy on their care of the patient. These measures are described below.

Approximately four weeks after discharge, a research assistant contacted all subjects to complete the CSQ and to report on their compliance with aftercare. At that time, service records were examined, and one of the clinicians responsible for aftercare was contacted to rate compliance with attendance and medication.

From the time of the index admission, repeat hospitalizations at Canberra Hospital and at regional hospitals were documented from hospital records. The length of time a subject was at risk of readmission varied from four to 12 months depending on when the subject entered the study. The mean±SD risk time for the patients in the study was 7.9±3.2 months in the control group and 6.5±2 months in the experimental group.

Measures

Health of the Nation Outcome Scales. The HoNOS (12) was developed in the United Kingdom for use as a routine measure of service outcome in the areas of psychological and social functioning. The 12 observer ratings in the scale are for disruptive or aggressive behavior, suicidality, self-injury, substance abuse, cognitive problems, physical debility, hallucinations and delusions, depressed mood, social relationships, living conditions (self-care), occupation of time, and other problems.

Raters are trained to ensure consistency in application, but the scale is not technical and does not demand clinical interpretation. In this study, the research officer was trained to use the scale; the officer then trained the hospital nursing staff who administered the scale.

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire. For the study, the 15-item CSQ (13,14,15) was reduced to nine items, each scored on a 4-point scale. Scores on the items were summed. Possible scores thus ranged from 0 to 36, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. The scale was reliable (Cronbach's alpha=.70).

The impact of advocacy. At hospital discharge, the physician and nurse principally responsible for each patient were asked whether routine advocacy and experimental advocacy made management of each subject easier (scored as +1), had no effect (scored as 0), or made management more difficult (scored as -1).

Compliance with aftercare. After examining the outpatient notes and questioning the responsible clinician, the researcher rated each patient's follow-up attendance and medication compliance as poor (rated 0), fair (rated 1), or good (rated 2).

Statistical analysis

The control and experimental groups were compared using appropriate t tests and chi square tests. When cell numbers were small, Fisher's exact test was used. Time between hospitalizations was analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards model, which allows for multiple hospitalizations of different lengths (16). This approach was appropriate for subjects in this study, who may have been hospitalized more than once.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

The sample of 105 subjects consisted of 63 men and 42 women. Their mean ±SD age was 36.3±14.3 years. Seventy-five subjects (71 percent) had never married, and 12 (11 percent) were divorced or widowed. Fifty-three subjects (51 percent) had a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia, and 43 (41 percent) had an affective disorder. The mean±SD HoNOS score for the total sample was 13.7±6.1.

No significant differences were found between the experimental and control groups in sex, age, marital status, diagnostic composition, or severity of disturbance as measured by the HoNOS. A larger proportion of the control group had experienced involuntary hospitalization before the study, but this difference was not statistically significant.

Satisfaction with hospital care

CSQ scores were first recorded three days after hospital admission. The scores reflected subjects' satisfaction with ordinary hospital care up to the time at which personal advocacy started. The mean±SD satisfaction scores for the experimental and control groups were very similar at this time (16±7.3 and 15.5±8.5, respectively).

At follow-up, an average of four weeks after discharge, patients used the CSQ to rate their satisfaction with hospital care. The mean±SD score of 18±6.4 for the experimental group indicated that satisfaction had increased. The control group's score of 14.7±8.9 indicated that it had deteriorated. The improvement in satisfaction in the experimental group was highly significant (Mann-Whitney U=977, p=.001)

Impact on care

Nursing staff reported that personal advocacy made patient management easier; their mean±SD rating was .5±.5 on a scale from -1 to 1. The mean rating of physicians was .7±.5, indicating a greater positive impact on patient management. Both groups reported no impact from routine advocacy (ratings of 0 for both).

Outcome

Duration of hospitalization. The mean±SD length of stay was 29±25 days for the control subjects and 24±16 days for the experimental subjects. This difference was not significant and was explained by the prolonged stays of three control subjects.

Compliance with aftercare. The measure of compliance with attendance during follow-up, which was rated from 0 to 2, indicated that attendance was significantly better in the experimental group than in the control group (means of 1.6±.7 and 1.2±.8; t=2.5, df=96, p=.01). The difference in medication compliance was not significant (1.4±.8 for the experimental group and 1.2±.9 for the control group).

Community tenure and rehospitalization. Twelve of the 53 experimental subjects (23 percent) and 23 of the 52 control subjects (44 percent) were involuntarily rehospitalized in the follow-up period (χ2=5.5, df=1, p=.02). The 12 experimental subjects had 16 rehospitalizations, a rate of 1.3 per person; the 23 control subjects had 45 rehospitalizations, a rate of two per person. As noted, the control group had a greater history of involuntary hospitalization before the study, but the difference was not significant. The control group and the experimental group had similar rates of voluntary rehospitalization; five experimental group members (9 percent) and eight control group members (15 percent) were rehospitalized voluntarily during the follow-up period.

Analysis of variance indicated that personal advocacy was the most significant factor in the lower rehospitalization rate in the experimental group; (F=5.9, df=1, 102, p<.02, for the effect of advocacy; F=4.9, df=1, 102, p<.03, for the effect of previous hospitalizations).

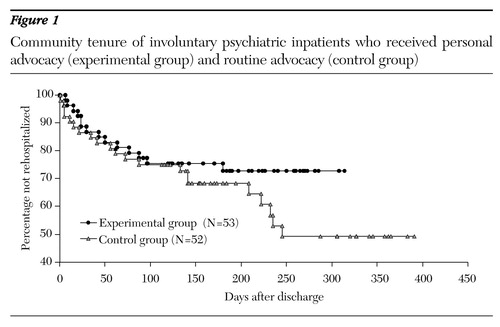

Figure 1 shows the survival curve for community tenure—that is, the percentage of subjects who were not rehospitalized.

A Cox proportional hazards model with multiple hazards per subject (16) showed that the relative risk for involuntary readmission among the control subjects was 2.08 times higher than the risk for the experimental subjects (p<.004).

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, a group of psychiatric inpatients who received personal advocacy during the whole period of involuntary hospitalization was compared with a group who received routine advocacy and legal rights protection at the gateway to commitment for involuntary treatment. The effects of the personal advocacy approach were striking. Both groups were similar in demographic characteristics, diagnosis, and severity of illness. Before and after hospitalization, all subjects were approached identically by the health system; the clinicians responsible for aftercare rarely knew whether the subject had received personal advocacy. The type of advocacy was the only significant difference between the two groups.

The most impressive findings were the experimental group's greater satisfaction and their lower rate of involuntary rehospitalization. During the follow-up period, 12 of 53 experimental subjects (23 percent) were involuntarily rehospitalized, compared with 23 of 52 control subjects (44 percent). In both groups some subjects were rehospitalized multiple times; however, the number of rehospitalizations in the control group was three times the number in the experimental group. Survival analysis underscored this finding, indicating that the odds of rehospitalization for the experimental subjects were less than half the odds for the control subjects. In the seven months of follow-up, the control subjects spent 250 more days in the hospital, at a cost of approximately $150,000 (Australian).

What accounted for the improved compliance and lower rehospitalization rate among the experimental subjects? The subjects' initial satisfaction and the length of the index involuntary hospitalization were about the same for both groups. Yet patients in the experimental group were significantly more compliant with attendance at aftercare, and they were significantly less likely to be rehospitalized.

The difference in compliance with aftercare appears to be a consequence of the difference in the experience of hospital treatment. For the experimental subjects, satisfaction with hospital care improved with the passage of time, whereas for the control subjects it deteriorated. The difference in satisfaction between the groups was significant.

Secondly, the subjects were highly aware of the continuing personal advocacy but much less aware of the routine advocacy and legal representation that protected their rights at commitment. Routine advocacy was delivered when the subjects were most ill, and their recollection of this time was often hazy. We also believe that routine advocacy addressed only the part of patients' needs that the institution felt was important. The needs that were more important personally to the patient were for information about and involvement in treatment decisions. Their wider personal and social needs, which are often overlooked in the treatment of acute illness, also needed attention. The personal advocate became a companion through an alien and frightening experience of illness and institutional treatment.

The positive attitude that clinical staff developed toward personal advocacy was unexpected. Many had been hostile at the project's inception, viewing it as an intrusion and an implication that they ignored patients' rights and needs. Staff approval, along with patients' increased satisfaction and better compliance, suggests that advocacy reduced the antagonism between staff members and patients. The question of why hospital case management may not address such antagonism and may neglect some patients' needs is an interesting one. We have observed this situation too widely to attribute it to weaknesses of a particular hospital. We believe that negotiation of consent is a vital ingredient of high-quality care (8), and it is often negated by the processes of involuntary detention.

The data collected do not allow us to conclude that the positive effects we observed flowed from the particular model of advocacy used. The personal advocacy model was compared with a model of routine rights advocacy, which did not continue beyond the gateway to commitment. The effectiveness of personal advocacy may come from the continuity of advocacy or the presence of an interested companion throughout the period of involuntary care. The model itself may thus be irrelevant. The professional advocate in the study was senior, confident, well qualified, and well supported. Other applications of the personal advocacy model may not be able to employ such a well-qualified advocate, which may affect patients' outcome. These questions can be resolved only by research that compares different models.

However, the experience of others (10,11) suggests that the model of advocacy will be important and that the model studied here is an effective one. It is effective because the advocacy is provided in a proactive negotiation driven by needs rather than being an adversarial reaction to a complaint after rights have been infringed. The advocate in this project was well trained in a well-described role and operated within the hospital but answered to an independent body (10).

Overall, the results appear to confirm the hypotheses that prompted this study. The personal advocacy approach described here represents the patient's needs and best interests and accompanies the patient through the course of compulsory treatment. This approach was associated with measurable improvements in treatment satisfaction, compliance, and, especially, the rate of involuntary rehospitalization. The study also showed that personal advocacy is justified not only on the grounds of ethics, justice, or rights; it also appears to improve the quality of care and the experience of both patients and staff. This approach to advocacy may save money by improving compliance with aftercare and reducing hospital use.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Commonwealth of Australia as part of the innovative grants project of the National Mental Health Strategy (grant 23012). During this project Dr. Rosenman and Ms. Newman were employed by the Government of the Australian Capital Territory.

Dr. Rosenman is a visiting fellow and Ms. Korten is research officer at the Centre for Mental Health Research at the Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 0200, Australia (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Newman is policy officer in the Health Department of Western Australia in Perth.

Figure 1. Community tenure of involuntary psychiatric inpatients who received personal advocacy (experimental group) and routine advocacy (control group)

1. Greenberg WM, Moore-Duncan L, Heiron R: Patients' attitude toward having been forcibly medicated. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law 24:525-532, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

2. Friese FJ: The mental health service consumer's perspective on mandatory treatment. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 75:17-27, 1997Google Scholar

3. Kaltaila-Heino R, Laippala P, Salokangas RKR: The impact of coercion on treatment outcome. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 20:311-322, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lidz CW, Hoge SK, Gardner W, et al: Perceived coercion in mental hospital admission. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1034-1039, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Svensson B, Hansson L: Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric care. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 90:379-384, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Spiessl H, Spiessl A, Cording C: Die "ideale" stationar-psychiatrische Behandlung aus Sicht der Patienten ["Ideal" inpatient psychiatric treatment from the viewpoint of patients]. Psychiatrische Praxis 26:3-8, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

7. Bennett NS, Lidz CW, Monahan J, et al: Inclusion, motivation, and good faith: the morality of coercion in mental hospital admission. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 11:295-306, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Etchells E, Sharpe G, Walsh P, et al: Bioethics for clinicians: I. consent. Canadian Medical Association Journal 155:177-180, 1996Google Scholar

9. Stewart MA: Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Canadian Medical Association Journal 152:1423-1433, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

10. Olley MC, Agloff JRP: Patients' rights advocacy: implications for program design and implementation. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:368-376, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Stone AA: The myth of advocacy. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 30:819-822, 1979Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Wing J, Curtis R, Beecor A: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales. London, Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1996Google Scholar

13. Atkisson CC, Zwick R: The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire: psychometric properties and correlation with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning 5:233-237, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Greenfield TK, Atkisson CC: Progress toward a multifactorial service satisfaction scale for evaluating primary care and mental health services. Evaluation and Program Planning 12:271-278, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al: Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning 2:197-207, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Korn EL, Graubaud BI, Midthune D: Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: choice of the time scale. American Journal of Epidemiology 145:72-80, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar