Effects of Discharge Planning and Compliance With Outpatient Appointments on Readmission Rates

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined whether patients discharged from inpatient psychiatric care would have lower rehospitalization rates if they kept an outpatient follow-up appointment after discharge. METHODS: Complete data were collected in 1998 on 3,113 psychiatric admissions in eight Southeastern states; 542 were readmissions. Patients' health care was managed by United Behavioral Health of Georgia (UBH-GA), which encouraged inpatient facilities to ensure that an outpatient appointment was scheduled for all discharged patients. UBH-GA contacted outpatient providers to determine whether patients kept at least one appointment. Rehospitalization rates were calculated for 90, 180, 270, and 365 days after discharge to examine effects over time of keeping an initial appointment. RESULTS: Of the 542 patients who were rehospitalized, 136 kept at least one outpatient appointment after discharge from their initial admission; 406 did not. For patients who did not keep an appointment, rehospitalization rates increased over time, ranging from 15 percent to 29 percent. For patients who kept an outpatient appointment, the rehospitalization rate remained the same over time, about 10 percent. The 270- and 365-day rehospitalization rates and the aggregated annual rates were significantly higher (p>.01) for patients who did not keep an appointment. CONCLUSIONS: Patients who did not have an outpatient appointment after discharge were two times more likely to be rehospitalized in the same year than patients who kept at least one outpatient appointment. Aggregated annual rates indicated that patients who kept appointments had a one in ten chance of being rehospitalized, whereas those who did not had a one in four chance.

Readmission rates for psychiatric care have been under close scrutiny since the 1980s, when lengths of inpatient stays began to decrease sharply as a result of both the philosophy of deinstitutionalization and the rise of managed health care. Concern has been expressed that managed care has lost sight of the needs of patients while concentrating instead on cost containment (1234). Arguably, managed care has changed the focus of inpatient hospitalization to acute stabilization of the patient rather than primary treatment. Once the patient is stabilized, care is received from outpatient providers at less acute levels of treatment.

Rehospitalization rates have long been used to determine the effectiveness of inpatient treatment. Readmission is a cause for concern, as it is not only a step backward in treatment but also a costly alternative to effective and efficient outpatient care. Given the current concerns about shorter lengths of stay, readmissions call into question the quality of care initially received; specifically, they raise the issue of premature discharge. The results of studies have been contradictory; some have found length of stay to be a predictor of readmission (123,5), whereas others have reported that it is not a factor in readmission (6789).

Lyons and colleagues (8) postulated that data on length of stay is confounded because no empirical research has been done to determine whether readmission actually represents a failure of the initial hospitalization. Their study clearly demonstrated that readmissions do not indicate failure of the index hospitalization or premature discharge; they suggest instead that recidivism may be due to a failure in discharge planning and outpatient follow-up. To date, few studies have examined the impact of discharge planning; however, the majority have found that noncompliance with outpatient follow-up is a strong predictor of readmission (6,10111213).

Most of the research examining predictors of readmission has focused primarily on factors associated with the index hospitalization and not with risk factors associated with aftercare services, such as those provided at community mental health centers or by private mental health care providers (1234567,910111213). The failure to look at aftercare services seems surprising, because inpatient care has shifted from being long-term care to crisis stabilization, with continued care coordinated through outpatient services.

United Behavioral Health of Georgia (UBH-GA) currently coordinates behavioral health benefits for 900,000 members insured by United HealthCare in eight Southeastern states. In 1997 an increase in the readmission rate of UBH-GA members coincided with UBH-GA's acquiring new members in new states. The rising readmission rate was a cause for concern, as it meant that some members were not progressing in treatment but were decompensating.

Based on the literature and anecdotal cases, it was hypothesized that the increased readmission rate for UBH-GA patients was not due to failure of the initial hospitalization or to premature discharge, because patients were stable at the time of discharge. Rather, it was attributed to a failure in discharge planning. Because of the recently acquired membership in new states, UBH-GA did not have long-standing relationships with the providers. Thus it was conceivable that these providers were not extending care beyond hospitalization.

Readmission rates are commonly used in the health care field as a quality indicator; specifically, rates of readmission 30, 90, and 180 days after discharge are examined. The standard quality-of-care marker used in the industry is a readmission rate lower than 15 percent in 30 days. However, little research exists on predictors of readmission in the private managed care sector. In part, tracking patients is difficult because of the lack of oversight of admissions and the range of choices of facilities available to the insured population. UBH-GA is structured as a health maintenance organization, with precertification required for all levels of service; UBH-GA provides clinical oversight of the choice of facilities and treatment planning. Because of these factors, large-scale interventions can be more easily implemented in an effort to improve the health and well-being of members and to contain medical costs. The structure also facilitates the measurement of the efforts of these interventions.

This prospective study was undertaken to increase the rate of outpatient appointments after discharge and to determine whether keeping at least one outpatient appointment would have an effect on patients' rehospitalization rates. We hypothesized that patients who kept an outpatient appointment after discharge from the index admission would have lower rehospitalization rates at 90-, 180-, 270-, and 365-day intervals than patients who did not keep an outpatient appointment. The expanded window of time for examining rates— instead of the 30-day industry standard— was used to determine the long-term impact of discharge planning.

In essence, we hypothesized that when continuation of care after discharge was ensured, patients would progress in treatment instead of decompensating and needing rehospitalization. The effectiveness of keeping outpatient appointments was determined by comparing rehospitalization rates of patients who kept an appointment after discharge and those who did not using differences in proportions testing (14).

Methods

All members whose coverage was managed by UBH-GA in 1998 were eligible for this study. Active participants were those who were admitted for inpatient care for a psychiatric condition at any time in 1998. UBH-GA asked facility staff to begin discharge planning with patients at the time of admission, which included educating patients about the importance of continued treatment after discharge and scheduling patients for a follow-up outpatient appointment with an appropriate care provider. Partial hospitalization programs were considered an inpatient level of care. For patients placed in partial hospitalization programs after inpatient treatment, the partial hospitalization program was asked to do the discharge planning and appointment scheduling. The outpatient intervention, which was not controlled for, ranged from intensive outpatient programs to individual therapy to medication management sessions.

At discharge, the facilities communicated the time and date of the outpatient appointment and the provider's name to the member and to UBH-GA. Within three days after the scheduled appointment, UBH-GA contacted the outpatient provider to determine whether the member had complied with the discharge plan. When a member had not complied, or when no outpatient appointment had been arranged for the member before discharge, UBH-GA contacted the member to encourage him or her to continue in treatment and, if the member requested it, to schedule an outpatient appointment. UBH-GA then followed up on these patients to determine whether they kept the outpatient appointment. Compliance with at least one appointment after discharge was tracked for all admissions.

Because receipt of insurance benefits requires precertification (or certification within 24 hours for emergency care), UBH-GA is able to collect data for all rendered services. In addition, because of its network of facilities and outpatient providers, UBH-GA has been able to form collaborative relationships in coordinating care by having inpatient facilities arrange for outpatient intervention and by receiving confirmation of compliance from the outpatient providers.

Data were collected on every member hospitalized in 1998. The dataset included demographic variables, admission date, discharge date, facility, attending psychiatrist, diagnosis, type of outpatient intervention, outpatient appointment date, and compliance with outpatient treatment. Hospitalizations that were readmissions— that is, patients hospitalized again at any point in 1998— were coded. The index or initial admission for each rehospitalized patient was identified.

Results

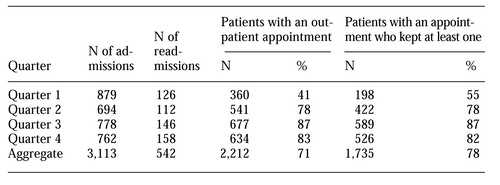

During 1998 data were collected on a total of 3,234 admissions. Data were missing for some admissions because of exhaustion of benefits, termination of the policy, or discharge to jail, and data were incomplete for 164 admissions. Complete data were available for 3,113 admissions. Table 1 shows the number of patients admitted and readmitted for each quarter of 1998 as well as the number of patients for whom discharge planning was done — that is, for whom an outpatient appointment was made— and the number who complied with an initial outpatient appointment.

At the end of the first quarter of 1998, data indicated that only 41 percent of all hospitalized patients had an outpatient follow-up appointment scheduled for them at the time of discharge. As we believed from the outset, the failure to arrange follow-up care was mostly due to a lack of coordination of care within the provider networks for the new membership. UBH-GA communicated the need for discharge planning to the contracted facilities early in 1998. As Table 1 shows, scheduling of outpatient appointments before discharge increased to 87 percent by the third quarter (an average of 71 percent for the year).

Annual aggregated data shown in Table 1 indicate that among the 2,212 patients for whom an outpatient appointment was scheduled before discharge, 1,735, or 78 percent, kept the appointment.

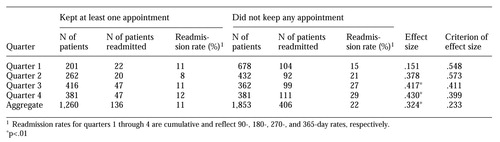

Of the 3,113 hospitalizations that occurred in 1998, a total of 542 were readmissions following an index admission that same year. To determine whether compliance with follow-up care affected rehospitalization rates, rates were calculated for patients who kept at least one follow-up appointment after the index admission and for those who did not. Of the 542 patients who were rehospitalized, 136 kept at least one outpatient appointment after the index hospitalization, and 406 did not.

The mean±SD age of the patients who were compliant and that of those who were not compliant with the appointment were virtually identical (39.2±11.2 years and 39.6±9.6 years, respectively). Most patients in both groups were female; 81 patients (60 percent) who kept their appointment were female, compared with 211 (52 percent) of those who did not. Significance testing using a two-tailed nonparametric test showed that the gender differences between the two groups were not significant. Data on race were not obtained.

The mean±SD length of stay for the patients who kept an appointment was greater than that for those who did not (5.5±.4 days versus 4.8±.6 days). However, a one-tailed nonparametric t test indicated that length of stay did not differ significantly between the two groups. The most common diagnostic categories were the same for each group: alcohol dependence and major depression.

Data were analyzed cumulatively to examine the impact over time of keeping at least one outpatient follow-up appointment. Cumulative readmission rates were calculated, yielding 90-, 180-, 270-, and 365-day readmission rates for the two groups. As shown in Table 2, patients who did not keep an appointment after the index admission had higher rates of readmission at all time points than patients who did. Over time, the rate of readmission increased for patients who did not keep an appointment, while the rate remained constant for patients who kept an appointment. That is, the longer a patient went without an appointment, the greater was the likelihood of readmission. As Table 2 shows, significant differences in readmission rates were found between groups.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study indicate that hospitalized patients who did not comply with at least one outpatient appointment after discharge were two times more likely to be rehospitalized than those who kept at least one appointment after discharge. The study found strong associations (p>.01) between keeping an outpatient appointment and being less likely to be rehospitalized during the third quarter of 1998 (the 270-day rehospitalization rate) and the fourth quarter of 1998 (the 365-day rehospitalization rate). A similar strong association was found for the 1998 aggregate rate of readmission. These results indicate that the positive benefit of keeping an outpatient appointment was sustained over time.

More important, time appeared to be a more critical factor for patients who did not keep an appointment. For this group the rate of rehospitalization increased as the time since the initial admission increased; no such increase in rates over time was found for patients who kept at least one outpatient appointment after discharge.

The results of this study support the benefits of continued outpatient care for recently hospitalized patients, at least for those who keep one appointment. The results also reinforce the need to look at rehospitalization due to the lack of outpatient follow-up, not only at factors associated with the inpatient stay. As discharge planning improved at the inpatient facilities in this study, so did rates of patients' compliance with outpatient follow-up. Most likely the increase in compliance can be attributed to the personal communications UBH-GA had with members who were initially noncompliant.

This study is not without its limitations. Most notably, keeping an outpatient appointment after discharge from the index admission did not prevent patients from being rehospitalized. Although the readmission rate did not increase over time for patients who kept an outpatient appointment, 11 percent of these patients were readmitted. These cases may have been medically complicated, or the patients may have been more chronically ill and unstable than the patients who were not readmitted.

In addition, an outpatient follow-up appointment was not in place for all patients at discharge. It is nearly impossible to schedule appointments for patients who leave against medical advice or who refuse aftercare. However, UBH-GA's performance standard is for inpatient facilities to have an outpatient intervention in place at discharge for 90 percent of patients.

Furthermore, the study did not control for the type of outpatient appointment. This point alone demands further study, as the variation in type and intensity of aftercare plans could have a strong impact on the continued stabilization and treatment of recently hospitalized individuals. In addition, patients' compliance with discharge planning was not followed beyond the first outpatient appointment; thus patients who went to the first appointment may have subsequently dropped out of treatment.

Because of the relationship between time and rehospitalization discussed above, the elapsed time between discharge and the outpatient appointment might also be related to the subsequent readmission. Although the goal was to make appointments within 72 hours of discharge, in reality the dataset showed that a number of patients waited several weeks between discharge and outpatient follow-up. In part, the extended times were due to patients' canceling and rescheduling appointments and not having transportation, and to some providers' not being able to see patients for several weeks.

Questions remain, but the data are compelling. Keeping an outpatient appointment after hospital discharge has an impact on the rate of rehospitalization. Stabilization from inpatient care appears to be sustained over time for patients who keep follow-up appointments. The rate of rehospitalization increased over time for patients who did not keep an appointment but not for patients who kept one. On the basis of the 365-day rehospitalization rate, patients in this study who kept an appointment had a one-in-ten chance of being rehospitalized; for patients who did not keep an appointment, the chances were one in four.

Examining rates of readmission beyond the industry standard of 30 days revealed the sustained effect of discharge planning for hospitalized patients. It appears essential that psychiatric inpatients have postdischarge outpatient appointments in place to minimize relapse. Health care clinicians involved in the treatment of hospitalized patients need to ensure continuation of care through outpatient services. Aggressive outreach efforts should be considered for patients who are noncompliant with discharge planning.

Furthermore, researchers examining rehospitalization should focus on discharge planning, not just factors associated with the admission. The 30-day rehospitalization rate may be the best indicator of the effectiveness of the care received during an admission, but it does not capture the impact of outpatient interventions after discharge. The results of this study support the need to look at the continuum of care in relation to rehospitalization rates and to accomplish that by using rehospitalization rates of longer than 30 days.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brian Cuffel, Ph.D., and Saul Feldman, M.D., for insightful and constructive reviews of the manuscript. They also thank Mary Gueh, Felisa Paul, and Joyce Tolson for following up on the outpatient appointments.

The authors are affiliated with United Behavioral Health. Dr. Nelson is regional clinical operations director and Dr. Axler is regional medical director in Atlanta, and Dr. Maruish is director of quality improvement in Minnetonka, Minnesota. Send correspondence to Dr. Nelson at United Behavioral Health, 4170 Ashford Dunwoody Road, Suite 100, Atlanta, Georgia 30319 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Number of admissions and readmissions per quarter for 3,113 patients hospitalized in 1998, the number for whom a follow-up outpatient appointment was made, and the number who kept at least one appoinment

|

Table 2. Readmission rates among 3,113 patients hospitalized in 1998, by whether or not they kept at least one outpatient follow-up appointment after discharge

1. Appleby L, Desai PN, Luchins D, et al: Length of stay and recidivism in schizophrenia: a study of public psychiatric hospital patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:72-76, 1993Link, Google Scholar

2. Swett C: Symptom severity and number of previous psychiatric admissions as predictors of readmission. Psychiatric Services 46:482-485, 1995Link, Google Scholar

3. Gruber JE: Paths and gates: the sources of recidivism and length of stay on a psychiatric ward. Medical Care 20:1197-1208, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Panzarino PJ, Kellar J: Integrating outcomes, quality, and utilization data for profiling behavioral health providers. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow 8:27-30, 1994Google Scholar

5. Rosenheck R, Massari L, Astrachan BM: The impact of DRG-based budgeting on inpatient psychiatric care in Veterans Administration medical centers. Medical Care 28:124-134, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, et al: Predicting the "revolving door" phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:856-861, 1995Link, Google Scholar

7. Swiggar ME, Astrachan B, Levine MA, et al: Single and repeated admissions to a mental health center: demographic, clinical, and service use characteristics. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 37:259-266, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Lyons JS, O'Mahoney MT, Miller SI, et al: Predicting readmission to the psychiatric hospital in a managed care environment: implications for quality indicators. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:337-340, 1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Knights A, Hirsch SR, Platt, SD: Clinical change as a function of brief admission to hospital in a controlled study using the Present State Examination. British Journal of Psychiatry 137:170-180, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Marken PA, Stanislav SW, Lacombe S, et al: Profile of a sample of subjects admitted to an acute care psychiatric facility with manic symptoms. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 28:201-205, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

11. Polk-Walker G, Chan W, Meltzer A, et al: Psychiatric recidivism prediction factors. Western Journal of Nursing Research 15:163-176, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Casper ES, Romo JM, Fasnacht RC: Readmission patterns of frequent users of inpatient psychiatric services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1116-1117, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Colenda CC, Hamer RM: First admission young adult patients to a state hospital: relative risk for rapid readmission. Psychiatric Quarterly 60:227-236, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar