Use of Community Support Services by Middle-Aged and Older Patients With Psychotic Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study sought to determine the degree to which use of community services is related to predisposing, enabling, and need factors among older patients with psychotic disorders who live in the community and to assess whether high use of community services is associated with improving or declining psychopathology. METHODS: The sample consisted of 89 middle-aged and elderly community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders. Assessments at baseline and two follow-ups at six-month intervals included measures of psychopathology, well-being, and social adjustment, in addition to the frequency of use of 17 formal community services in three categories—psychological, social, and daily living services. RESULTS: Ninety-two percent of patients reported use of community support services. The mean number of annual service contacts per patient was 36.6 for psychological services, 81 for social services, and 39.7 for daily living services. High users of psychological services were younger and experienced more severe positive psychotic symptoms and depressive symptoms. High users of social services were of higher socioeconomic status, more likely to be female, and had a longer history of psychosis, more cognitive deficits, and more severe negative psychotic and depressive symptoms. Patients who used daily living services were older, had poorer functional health status and more cognitive deficits, and had more severe negative psychotic and depressive symptoms. A trend was noted for high users of social services to experience relief from depressive symptoms over time. CONCLUSIONS: Use of community services is common among older outpatients with psychotic disorders, but its frequency varies as a function of patient characteristics.

The cost of health care in the United States continues to increase exponentially, with current costs exceeding those in 1940 by 200 times (1). Schizophrenia, one of the most costly psychiatric disorders, results in the annual expenditure of $19 billion in treatment costs alone (2) and an additional $80 billion in lost productivity and other indirect costs. Paradoxically, spiraling costs have not coincided with increased accessibility to mental health care services. Fewer than 15 percent of individuals with alcohol, drug, and mental health disorders seek mental health treatment within a six-month time frame (3).

Community support services have long served as an important adjunct to physician care and treatment for patients with chronic mental illness. These services may be even more critical for older psychiatric patients, who may be experiencing functional health decrements or facing age-related reductions in social and family supports. Community services may play an important role for these patients by improving socialization, increasing social support, teaching skills, increasing mobility or activity levels, and providing opportunities for intrapsychic or interpersonal growth and insight.

Although community services can be quite variable in content and goals, they tend to share several prototypic features. They tend to be highly elective, usually requiring substantial patient initiative. They are promoted as being low-cost and readily available. They are often targeted at disadvantaged populations, are frequently offered by paraprofessionals, and typically have a group rather than an individual focus.

Previous studies of mental health services for patients with chronic mental illness have included services associated with acute, crisis-oriented support or custodial care, such as physician visits, hospitalizations, and medication management. Using these parameters, Faccincani and colleagues (4) reported that psychiatric symptoms and social functioning were not related to patients' use of services. However, other studies have suggested demographic and diagnostic correlates of high service use. In one study, repeat users of psychiatric emergency services were more likely to be young, male, unmarried, unemployed, and nonwhite and to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia (5). Similarly, Thornicroft and colleagues (6) identified predictors of increased service use among patients with schizophrenia. They included living alone, being unemployed, and being unmarried. None of these studies included older patients with psychotic disorders or examined community services as an adjunct to health care utilization.

Older Americans, in general, have been identified as heavy users of health care services (7). Higher use of health care and social services by elderly persons living in the community has been associated with increased frailty, older age, living alone, being an urban resident, increased depressive symptoms, and increased knowledge of, satisfaction with, and orientation to the formal service delivery system (8,9,10,11,12). Recent evidence suggests that elderly patients with schizophrenia incur substantially higher mental health care costs than middle-aged patients (13).

Older patients with psychoses may vary from their younger counterparts in their need for and use of community support services. First, older patients are more likely to live alone, have fewer surviving family members, and experience social isolation. Therefore, community support services may provide a more primary function of social support and interaction (14). The quantity of social support available has been shown to predict longevity among patients with schizophrenia (15).

Second, community support services may provide a referral network for older patients to obtain housing, financial and legal support, health information, and treatment for comorbid medical conditions. Service system integration has been shown to predict superior housing outcomes for persons with severe mental illness (16). Third, the emphasis of community support services on social and physical functioning may be particularly helpful for older patients whose psychotic symptoms have been stabilized after multiple trials of antipsychotic medications.

Greater use of community support services among community-dwelling elderly persons with psychoses may reflect both clinical improvements, such as less social isolation and more activity, and clinical declines. For example, psychotic symptoms may create an increased need for support services. Therefore, in studies of variables that predict service use, it is important to recognize various categories of variables. A model of service use proposed by Anderson and Newman (17) included three categorizations of predictor variables: predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors. Predisposing factors include demographic and background variables such as age, gender, educational background, and socialization. Enabling factors are those related to service costs, accessibility, and affordability. Need factors include measures of symptoms, medical status, disease severity, and distress.

The study reported here used a cross-sectional and a longitudinal design to address three primary questions. First, what kinds of community support services are used by older patients with psychotic disorders, and how consistent is their use across time? Second, what are the determinants of community support service use for these patients? Third, is high use of community support services associated with improving or worsening psychopathology?

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 89 consenting patients who had a psychotic disorder (most patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia) who were participating in a longitudinal cohort study at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), Clinical Research Center for late-life psychosis. The sample was recruited between 1993 and 1996 from the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Diego, the UCSD Medical Center and clinics, and the San Diego community. All the patients met DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria (18,19) for a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder at study entry and were at least 45 years of age. Patients needed to have sufficient physical and psychiatric stability to undergo periodic assessments required by the Clinical Research Center.

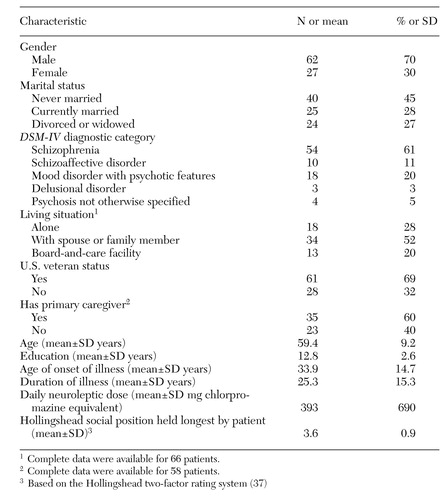

Exclusionary criteria were evidence of major neurologic disorders by history, current physical examination, or laboratory tests and a current diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence based on DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria. Two-thirds of the patients were on neuroleptic medication at the time of assessment. Approximately half of the patients were living with a spouse or a domestic partner. Nineteen patients (21 percent) were between ages 45 and 50; 24 (27 percent) were between ages 50 and 60; 33 (37 percent) were between ages 60 and 70; and 13 (15 percent) were between ages 70 and 80. Demographic and clinical variables are summarized in Table 1.

Procedures

Clinical assessments and psychosocial interviews, each lasting approximately two hours, were performed by trained staff interviewers at baseline and two consecutive six-month intervals.

Use of formal community services.

From a list of 17 possible formal community services, including psychological, social, and daily living services, the subjects were asked to name those used at least once during the past six months. Psychiatric appointments (including time spent with psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists) were included under the category of individual and family counseling unless the patient described the visits as medical management only. For each item endorsed, subjects also reported the approximate frequency of use: less than once a month, monthly, biweekly, weekly, two or three times a week, or daily. The number of services used was computed by multiplying each endorsed item by its estimated frequency over the previous six-month period. Test-retest reliability of the measure was assessed by readministering the questionnaire by telephone to 20 randomly selected subjects two weeks after the initial interview.

Other measures. The total number of negative life events reported during the preceding six months was assessed using the Psychiatric Epidemiologic Research Interview (PERI) (20,21). The Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SAPS and SANS) (22,23) were used to assess the severity of those symptoms. The 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) (24,25) was given to evaluate depressive symptoms. The Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB) (26) was used to assess overall quality of life (27). Social functioning and adjustment were evaluated by a modified Social Adjustment Scale (SAS), developed by Weissman and associates (28,29,30), which has been used widely in studies of patients with schizophrenia (31,32,33). To gauge subjects' access to emotional support, we used the mean score from a five-item scale developed by Pearlin and colleagues (34).

Statistical analyses

To test the ability of variables to predict community service use, discriminant function analyses were conducted using a stepwise algorithm with three sequential blocks representing predisposing, enabling, and need factors. In view of the exploratory nature of this first set of analyses, a somewhat liberal "F to enter" criterion of 1 was chosen for all steps in the analyses. An alpha criterion of .05, however, was chosen for the overall statistical significance of each discriminant function. Data transformations of independent variables to adjust for substantial deviations from the normal distribution followed the guidelines of Tabachnik and Fidell (35).

To assess the potential benefits of community service use for psychopathologic symptoms across three consecutive six-month assessments, we performed repeated measures 3 × 2 multivariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) (time periods by high or low service use) with a planned polynomial contrast. We hypothesized that more frequent users of community support services would experience a gradual improvement in psychotic and depressive symptoms over time.

Results

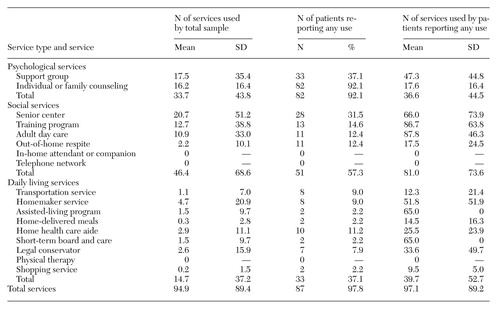

Test-retest correlations for data obtained two weeks apart with the subsample of 20 patients were high for psychological services (r=.98) and daily living services (r=.97), while social service use was replicated exactly (r=1). Table 2 shows the services used by the 89 patients over a one-year period, which was the sum of reported service use at baseline and at the first six-month follow-up. Subjects reported from 0 to 160 individual uses of formal community services.

The mean±SD number of service contacts was 94.9±89.4 for the year, or approximately two services per week. Of these, 36 percent were psychological services, 49 percent were social services, and 15 percent were daily living services. No significant differences in service use were found between patients with schizophrenia and those with other psychotic disorders, and these groups were combined for subsequent analyses.

Use of psychological, social, and daily living services were not significantly intercorrelated. When services use was compared across the three consecutive assessments, consistency of use was moderate to low. First and second assessments were correlated .65 for psychological services, .59 for social services, and .24 for daily living services. Second and third assessments were correlated .60 for psychological services, .64 for social services, and .42 for daily living services. In a subsample of 58 patients who completed an adjunct study investigating family support systems, the presence of a primary family caregiver (60 percent of the cases) was not significantly associated with use of community services.

A brief assessment of cognitive status with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (36) yielded scores from 17 to 30 of a possible 30 points. Higher scores indicate better cognitive functioning. Eight patients (9 percent) scored between 17 and 22, eighteen patients (20 percent) scored between 23 and 26, and the majority of patients (71 percent) scored 27 or greater. Mental status was weakly correlated with age (K=−.22, p=.038). Pearson correlations between service use, age, and cognitive status showed that psychological, social, and daily living services used over a one-year period were not correlated with either cognitive status or age. A dichotomous grouping of patients by age—patients under age 60 compared with those age 60 or older—also revealed no statistically significant differences in rates of psychological, social, or daily living services use.

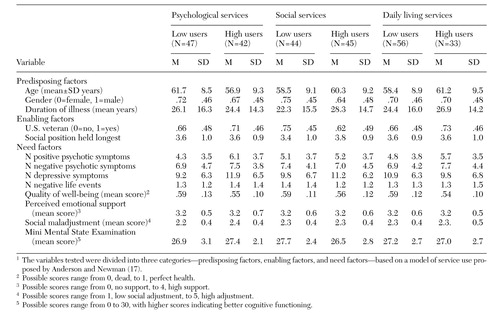

For each type of community service, the 89 patients were divided into high and low users based on median splits of the total number of services used over the one-year period. The cutoff numbers were 12 for psychological services, five for social services, and one for daily living services. This approach was suggested by the bimodal frequency distribution of service use. To assess the antecedents of service use, independent variables were first categorized as predisposing, enabling, or need factors according to the Anderson and Newman (17) model for service utilization.

Means and standard deviations for all predictor variables are shown in Table 3. The predisposing factors were age, gender, and duration of illness. Enabling factors were the longest held socioeconomic position using the Hollingshead two-factor rating system (37) and whether the patient was a U.S. veteran. Need factors consisted of eight variables assessing symptom severity, including positive and negative psychotic symptoms, depressive symptoms, cognitive status as measured by the MMSE, life circumstances (negative life events), well-being as measured by the QWB, perceived emotional support, and social dysfunction.

Discriminant function analyses were performed separately to predict use of psychological, social, and daily living services from the list of predisposing, enabling, and need factors. For psychological services, high users were younger, were more depressed, and experienced more positive psychotic symptoms (Wilk's lambda=.87, χ2=12.14, df=3, p=.007). High users of social services had higher socioeconomic status and longer duration of illness, were more likely to be female, and had more severe cognitive deficits, negative symptoms, and depressive symptoms (Wilk's lambda=.86, χ2=12.92, df=6, p=.044). Users of daily living services were older and had lower QWB scores (Wilk's lambda=.84, χ2=14.42, df=2, p=.013).

The patient sample had a fairly wide distribution of chronological age (45 to 80 years). Therefore, for the need factors that entered the discriminant function in the analyses described above, age interaction terms were tested as subsequent predictors. Two significant interactions with age were noted. First, the relationship between depressive symptoms and social service use varied by age (F to enter=3.86, p<.05). The association between more severe depressive symptoms and greater social service use was stronger for younger patients. Second, the relationship between severity of cognitive impairment and use of daily living services varied by age (F to enter=7.57, p<.05). Older age and cognitive impairment together produced a synergistic increase in the likelihood of using daily living services.

In a further exploration of age effects, an additional dichotomous variable—above or below age 60—was tested as a potential covariate or moderating factor for each of the multiple regression analyses predicting service use. This set of analyses was done to test whether middle-aged and older adults should be considered separately rather than assuming that age effects are linear. This dichotomous age categorization explained no additional variability in services used.

To assess the potential benefits of community service use on psychopathology across consecutive six-month assessments, a repeated-measures 3 × 2 multivariate ANOVA (time periods by high and low service use) was conducted to predict changes in depressive symptoms, positive psychotic symptoms, and negative psychotic symptoms. In these analyses, severity of psychopathologic symptoms did not vary over time by use of psychological services or daily living services. However, among users of social services, a trend was noted toward fewer depressive symptoms among high users compared with low users (t=1.80, df=78, p=.076).

Discussion and conclusions

Compared with the use of medical services, such as physician visits and hospitalizations, the use of community support services may require a greater level of patient initiative. Therefore, we chose a behavioral model for predicting service use. The service utilization model proposed by Anderson and Newman (17) includes predisposing, enabling, and need factors. The 89 patients who were recruited for this study reported a wide range of community service use, from none to almost daily use over a one-year period. The mean number of services used—two services a week—was high. The high mean use and the small proportion of patients reporting no service use indicate that community services play a prominent role in the lives of older patients with psychoses.

The rate of community service use found in this study is approximately twice the rate for normal subjects. Based on our assessment of the use of community support services among other geriatric populations, the number of services used by patients in this study is about the same as that used by community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer's disease (Grant I, Patterson TL, unpublished data, 1993–1998).

Frequency of service use varied considerably across consecutive six-month periods, with longitudinal correlations that were moderate (for psychological and social services) or low (for daily living services). This variability could not be attributed to poor reliability of the measure because two-week test-retest correlations were high. Therefore, patient demand for support services appeared to vary considerably with time, or else the supply of such services varied considerably. Part of this variability may be attributed to the cyclical environment in which many services are provided. Support groups, training programs, and other services that are designed around a short-term therapeutic model may predispose patients to regular three- to six-month shifts in participation, regardless of need.

In this sample of patients, service use was unrelated to gender, negative life events, or social maladjustment. Although use of psychological services was more prevalent among younger patients, older patients or those with a longer duration of psychotic illness were more frequent users of social services and daily living services. Therefore, older patients with psychotic disorders may follow an evolution of treatment that shifts from psychological to social services with increasing age and duration of illness. This pattern may represent an age-related transition in treatment focus from controlling symptoms to improving social well-being. However, we should note that this was not a long-term prospective study. An alternative explanation is that older patients with psychoses who have had symptoms for a longer time simply become disenchanted with support groups and individual counselors as a treatment milieu.

Age as a continuous variable was a significant factor in our analyses, and it had both direct and interaction effects. However, a dichotomous grouping of patients into middle-aged and older patients failed to explain any additional variance in service use. Therefore, although scientific investigations of older adults have traditionally included subjects age 65 and older to coincide with retirement and concomitant lifestyle changes, this demarcation may be less meaningful among patients with severe and persistent mental illness.

High users of services were also more depressed. This finding is consistent with previous findings in this patient cohort (27), which suggest that patients' well-being and life satisfaction are more closely associated with mood than with psychotic symptoms. Positive psychotic symptoms were more predictive of use of psychological services, whereas negative symptoms were more predictive of use of social and daily living services. Psychological services may be more likely to be initiated by family and formal care providers in response to increases in hallucinations, delusions, or bizarre behavior because they are viewed by others as more alarming or potentially dangerous. Negative symptoms, on the other hand, may produce greater distress among the patients themselves, leading to an increase in patients' perceived need for social and daily living services to combat social withdrawal and isolation.

Interestingly, social maladjustment had no unique predictive strength to discriminate high and low users of community services. One reason may be that the social maladjustment inherent in psychosis creates both a simultaneous need for support services (social isolation) and a deterrent from seeking them (paranoia or suspiciousness). These competing factors may also explain the surprisingly weak, but statistically significant, relationships of other need factors, such as psychotic symptoms, to service use.

Although our analysis of clinical benefits of service use involved only three assessments over a one-year period, a trend was found suggesting that high use of social services, but not psychological services, was associated with a relative reduction in depressive symptoms over this period. For older patients with psychotic disorders, social services may have some advantages over psychological services. Social services are more likely to be organized or led by peers, to be activity based, and to involve a heterogeneous mix of well elderly persons along with those who are physically or mentally ill. Therefore, older adults with chronic mental illness may benefit from these aspects of social services, which would provide both psychological support and increased self-efficacy for activity, mobility, and social integration.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. The study focused on patients who were living in the community, and thus it was not necessarily representative of severely ill inpatients. Nevertheless, as reported by Flynn (38), at least 80 percent of patients with schizophrenia live in noninstitutional community settings. The assessment of use of a limited number of community services without verification by collateral sources might also be viewed as a limitation. Nonetheless, given the social isolation of these patients and the limited availability of family caregivers, it may be difficult to find collateral sources of information about patients' use of services. Finally, we did not follow our patients longer than a year to assess the longer-term effects of community support services on psychopathology.

A future direction for this type of study is to examine patients' and family members' attitudes and beliefs about the accessibility and efficacy of services, as stressed by Wister (39). It will be important to determine if use of services is predominantly driven by perceived needs of patients, by accessibility of services, or by patients' knowledge and attitudes. Our data suggest that as patients with psychoses age, they may prefer, or be more frequently referred to, social support services as a form of treatment rather than to traditional group and individual counseling. The trend found in our data for use of social services to predict a decline in depressive symptoms provides additional support for such referrals. For clinicians caring for older patients with psychoses, integration of community social services in the psychiatric treatment plan is warranted by these preliminary data.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by grants MH-42840, MH-49671, MH-45131, and MH-51459 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); grant MH-49693, which supports the NIMH Geriatric Research Center in San Diego; the Sam & Rose Stein Institute for Research on Aging; and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Dr. Shaw is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, D.C. The other authors are with the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and with the San Diego Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Send correspondence to Dr. Patterson at the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92093-0680 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of 89 middle-aged and older patients with psychotic disorders

|

Table 2. Community support services used over one year by 89 middle-aged and older patients with psychotic disorders

|

Table 3. Mean values at baseline for variables that predicted low versus high use of three types of services among 89 middle-aged and older patients with psychotic disorders1

1. Kaplan RM: Quality of life, resource allocation, and the US health-care crisis, in Quality of Life in Behavioral Medicine Research. Edited by Dimsdale JE, Baum A. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 1995Google Scholar

2. Norquist GS, Regier DA, Rupp A: Estimates of the cost of treating people with schizophrenia: contributions of data from epidemiologic surveys, in Handbook of Mental Health Economics and Health Policy. Edited by Moscarelli M, Rupp A, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 1996Google Scholar

3. Regier DA, Shapiro S, Kessler LG, et al: Epidemiology and health service resource allocation for alcohol, drug abuse, and mental disorders. Public Health Reports 99:483-492, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

4. Faccincani C, Mignolli G, Platt S: Service utilization, social support, and psychiatric status in a cohort of patients with schizophrenic psychoses: a seven-year follow-up study. Schizophrenia Research 3:139-146, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Sullivan PF, Bulik CM, Forman SD, et al: Characteristics of repeat users of a psychiatric emergency service. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:376-380, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Thornicroft G, Bisoffi O, DeSalvia D, et al: Urban-rural differences in the associations between social deprivation and psychiatric service utilization in schizophrenia and all diagnoses: a case register study in northern Italy. Psychological Medicine 23:487-496, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Wolinsky FD: Health services utilization among older adults: conceptual, measurement, and modeling issues in secondary analysis. Gerontologist 34:470-475, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. McCaslin R: Reframing research on service use among the elderly: an analysis of recent findings. Gerontologist 28:592-599, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Schuckit MA, Tipp YE, Bucholz MC, et al: The lifetime rates of three major mood disorders and four major anxiety disorders in alcoholics and controls. Addiction 92:1289-1304, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Waxman HM, Carrier EA, Slum A: Depressive symptoms and health service utilization among the community elderly. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 31:417-420, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Zastowny TR, Roghmann KJ, Cafferata GL: Patient satisfaction and the use of health services. Medical Care 27:705-723, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Cafferata GL: Marital status, living arrangements, and the use of health services by elderly persons. Journal of Gerontology 42:613-618, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Cuffel BJ, Jeste DV, Halpain M, et al: Treatment costs and use of community mental health services for schizophrenia by age-cohorts. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:870-876, 1996Link, Google Scholar

14. Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Shaw WS, et al: The social networks of older schizophrenia patients. International Psychogeriatrics 9:89-102, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Christensen AJ, Dornink R, Ehlers SL, et al: Social environment and longevity in schizophrenia. Psychosomatic Medicine 61:141-145, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Rosenheck R, Morrissey J, Lam J, et al: Service system integration, access to services, and housing outcomes in a program for homeless persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 88:1610-1615, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Anderson K, Newman IF: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 51:95-124, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

19. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

20. Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP: Stressful Life Events and Their Contexts. New York, Rutgers University Press, 1984Google Scholar

21. Grant I, McDonald WI, Patterson T, et al: Life events and multiple sclerosis, in Life Events and Illness. Edited by Brown GW, Harris TO. New York, Guilford, 1989Google Scholar

22. Andreasen NC, Olsen S: Negative vs positive schizophrenia: definition and validation. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:789-794, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Andreasen NC: Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: definition and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:784-788, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Hamilton M: Standardised assessment and recording of depressive symptoms. Psychiatric and Neurological Neurochiropracty 72:201-205, 1969Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hamilton M: General problems of psychiatric rating scales (especially depression), in Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology. Edited by Pichot P, Olivier-Martin R. Basel, Switzerland, Karger, 1974Google Scholar

26. Kaplan RM, Anderson JP: A general health policy model: update and applications. Health Services Research 23:203-234, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

27. Patterson TL, Kaplan RIM, Grant I, et al: Quality of well-being in late-life psychosis. Psychiatry Research 63:269-281, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Weissman M, Paykel E, Siegel R, et al: The social role performance of depressed women: comparisons with a normal group. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 41:390-405, 1971Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Social Adjustment Scale Handbook: Rationale, Reliability, Validity, Scoring, and Training Guide. New York, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, 1990Google Scholar

30. Cooper P, Osborn M, Gath D, et al: Evaluation of a modified self-report measure of social adjustment. British Journal of Psychiatry 141:68-75, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Bellack A, Morrison K, Wixted J, et al: An analysis of social competence in schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 156:809-818, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Shaw WS, et al: Self-reported social functioning among older patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 27:199-210, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Paykel ES, Weissman MM: Social adjustment and depression: a longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry 28:659-663, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Pearlin L, Mullan J, Semple S, et al: Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 30:583-594, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Tabachnik BG, Fidell LS: Using Multivariate Statistics, 2nd ed. New York, HarperCollins, 1989, pp 86,347Google Scholar

36. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: "Mini-Mental State": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12:189-198, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Hollingshead AR: Two-Factor Index of Social Position. New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Press, 1965Google Scholar

38. Flynn LM: Schizophrenia from a family point of view: a social and economic perspective, in Schizophrenia: From Mind to Molecule. Edited by Andreasen NC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

39. Wister AV: Residential attitudes and knowledge, use, and future use of home support agencies. Journal of Applied Gerontology 11:84-100, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar