Health and Self-Care Practices of Persons With Schizophrenia

Abstract

Data on the self-care and health-related practices and health status of 22 outpatients with schizophrenia were collected from interviews using a series of health survey instruments and a review of patient records. The patients practiced fewer health-promoting behaviors than nonpsychiatric samples described in the literature and were at risk for premature death primarily due to overeating and smoking. They were most similar to persons with chronic physical illness in their perception of the locus of control of their health. More than half of the patients had physical conditions requiring medical management.

High morbidity and mortality rates have been consistently documented in psychiatric populations (1). Researchers have identified several factors that contribute to increased risk of physical illness in this population, including poor judgment about health needs, low socioeconomic status, and inadequate detection of physical illness by providers (1). People with schizophrenia are at increased risk for multiple and chronic social, cognitive, and behavioral deficits that may lead to inadequate health and self-care practices.

Although substantial evidence has supported the relationship between healthy lifestyle and health outcomes in nonpsychiatric populations, we could find only one published study that examined self-care behaviors of people with severe and long-term psychiatric illness (2). Most of the 58 study participants had received a physical examination within the past year, and more than half made regular dentist visits. With respect to lifestyle, 81 percent of the study participants reported moderate or no alcohol use, and 66 percent smoked cigarettes. Other health-related characteristics such as amount of sleep and exercise, weight, and eating habits were not reported.

An understanding of the health behaviors of people with schizophrenia is necessary to guide clinical treatment and program development to reduce morbidity in this population. The study reported here examined several health and self-care behaviors of outpatients with schizophrenia, described the incidence of morbidity in this group, and compared the findings for this group with those reported for other samples.

Methods

A convenience sample of 22 adults under age 40 with a diagnosis of schizophrenia was recruited in 1992 and 1993 from a psychiatric outpatient clinic serving high-risk clients with prolonged mental illness. The sample consisted of 13 men and nine women, with a mean age of 32 years. Seven were African American, one was Hispanic, and 14 were Caucasian. Three had not finished high school, ten were high school graduates, eight attended some college, and one was a college graduate. Seventeen subjects were unemployed due to disability, four worked in unskilled jobs, and one reported a job as a professional or manager.

Each subject was given a questionnaire packet that was completed in the presence of a researcher at the outpatient clinic. The questionnaires were administered orally to three subjects who reported difficulties with reading.

Behaviors that enhance health and well-being were assessed using the Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile (HPLP) (3). Self-care activities were assessed using the Denyes Self-Care Practices Instrument (DSCPI) (4). Risk for preventable death and chronic illness was assessed using the Health Risk Appraisal (HRA) (5). Perception of control over one's health state was measured by the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale Form B (MHLC-B) (6). Locus of control was conceptualized as internal or external, and external control as control by a powerful other or by chance. Additional data were obtained from psychiatric records.

All subjects had primary psychiatric diagnoses of schizophrenia. Five subjects had additional diagnoses of alcohol or substance abuse, and seven had a secondary personality disorder. The median number of previous hospitalizations was between five and six, with a range from 0 to 37. Scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale ranged from 30 to 70, with a median score of 55 and a mean of 52. Thus there was a broad range of global functioning ability in the sample.

On level of functioning, 13 of the subjects were rated as severely impaired by psychiatric symptoms. Seventeen had received relatively continuous treatment since their initial diagnosis. Medication regimens consisted of antipsychotics for 19 subjects, antidepressants for three subjects, antiparkinsonian medications for 15, and lithium for eight.

Results

To evaluate health-related behaviors in this sample, comparisons were made with findings from other published studies. Regarding lifestyle factors measured using the HPLP, sample subjects felt less self-actualized than subjects in a sample of blue-collar workers (7) (t=3.4, df=198, p<.001), reported fewer positive nutritional habits (t=2.9, df=198, p<.01), had less interpersonal support (t=2.2, df=198, p<.05), and practiced fewer health-enhancing behaviors (t=3.9, df=198, p<.01). No statistically significant differences between the two groups were found in health responsibility, exercise, or stress management. Subjects in the study engaged in fewer self-care behaviors, measured using the DSCPI, than young adult women under stress (8) (mean=58.4 for the study subjects, compared with 64.6 for the comparison sample).

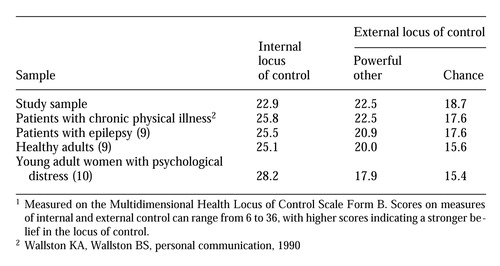

As Table 1 shows, sample subjects had a lower score on the measure of internal locus of control of their health (mean=22.9) compared with other groups, indicating a stronger belief that their health was not within their control. Sample means for the measures of external control were generally higher (mean=22.5 on the scale attributing control over health to powerful others and 18.7 on the scale attributing control to luck or chance), compared with the means for other groups. Sample subjects scored higher on measures of external control than healthy adults (9) and young adult women with psychological distress (10). Sample subjects were most similar in locus-of-control scores to groups with a diagnosis of epilepsy (9) and diagnoses of chronic conditions (Wallston KA, Wallston BS, personal communication, 1990).

The HRA examined exercise, nutrition, smoking, and alcohol use. In this sample only ten subjects reported adequate exercise, 18 reported eating adequate high-fiber foods, and 11 reported avoiding high-fat foods. Eighteen subjects were current smokers. Fifteen subjects reported sleeping ten or more hours a night.

Only five subjects admitted using small amounts of alcohol weekly. However, chart reviews revealed records documenting histories of substance abuse for 14 subjects. For nine subjects, substance abuse was a current treatment focus. Self-reported alcohol use and clinician observation differed; evidence suggested problems with excessive alcohol consumption for more than half of the sample.

As for self-assessment of health status, eight subjects rated their health as poor to fair, seven as good, and five as excellent. However, according to the HRA, a total of 18 subjects required changes in health behaviors to reduce the risk of premature death— 16 subjects needed to quit smoking and 13 subjects needed to reduce their weight.

A review of the psychiatric records revealed a considerable number of health risk factors, based on current and previous life stressors and effects of psychotropic drugs. During the past year, six subjects reported personal losses, and 16 had experienced psychosocial stressors that were rated severe to extreme by the clinicians who prepared the records. A history of physical trauma was documented in the records of three subjects. Physical health problems, documented in the psychiatric records of nine subjects, included mild to severe obesity, congenital deafness, premenstrual syndrome, hypertension, acne, and severe sleep apnea requiring a permanent trachea tube. Psychiatrically related medical conditions noted for four additional subjects included excessive water intake, elevated prolactin levels, and early tardive dyskinesia.

Discussion and conclusions

The study findings suggest that long-term psychiatric patients are less likely to perform self-care or health promotion activities, compared with nonpsychiatric populations. Compared with nonpsychiatric working-class subjects, subjects with schizophrenia had similar scores on three HPLP subscales and significantly lower scores on HPLP measures of self-actualization, nutrition, interpersonal support, and overall health promotion. On the DSCPI, sample subjects scored approximately 10 points below the mean for young women experiencing psychological distress.

On the MHLC, scores for patients with schizophrenia were similar to those for persons with chronic illnesses—lower on measures of internal locus of control and higher on measures of external locus of control. However, a lack of congruence between the MHLC scales and lifestyle practices has been reported (10). For people with a chronic illness who experience episodic, unexplainable symptom fluctuations, an adaptive coping mechanism may be to modify health beliefs toward an external locus of control. Based on HRA criteria, the most common negative health habits of this sample were smoking and overeating. Excessive alcohol consumption was also identified as a risk through record review, although subjects appeared to be reluctant to report this problem.

This study of health behaviors among young adult outpatients with schizophrenia points out several health behaviors likely to contribute to higher morbidity and mortality in this population. The evidence also suggests that other contributors to poor health include ongoing psychiatric symptoms, a high level of psychosocial stressors, and prior physical trauma. Although limited by a small, homogenous sample, this study suggested the potential contribution of poor health practices to the well-established association between psychiatric illness and deteriorated physical health. Further studies are needed to determine the validity of these findings and to identify predictors of healthy behavior in persons with severe mental illness.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by a grant from the University of Rochester Alumni Association and Sigma Theta Tau International.

Dr. Holmberg is affiliated with the Indiana University School of Nursing, 111 Middle Drive, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Kane is with the University of Virginia School of Nursing in Charlottesville.

|

Table 1. Mean scores of a study sample of 22 outpatients with schizophrenia and comparison samples on perceived locus of control of health1

1. Felker R, Yazel JJ, Short D: Mortality and medical morbidity among psychiatric patients: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:1356-1363, 1996Link, Google Scholar

2. Lieberman AA, Test MA: Health care practices and health status of the mentally ill in the community. Health and Social Work 12:29-37, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Walker SN, Sechrist LR, Pender NJ: The Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile: development and psychometric characteristics. Nursing Research 36:76-80, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Denyes MJ: Using Orem's theory for health promotion: directions for research. Advances in Nursing Science 11:13-21, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Doerr BT, Hutchins EB: Health Risk Appraisal: process, problems, and prospects for nursing practice. Nursing Research 30:299-306, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wallston KA Wallston BS, DeVellis R: Development of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) scales. Health Education Monographs 6:160-170, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Weitzel MH: A test of the health promotion model with blue collar workers. Nursing Research 38:99-104, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Campbell JC: Nursing study of two explanatory models of women's responses to battering. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Rochester, NY, University of Rochester, School of Nursing, 1986Google Scholar

9. DeVellis RF, DeVellis BM, Wallston BS, et al: Epilepsy and learned helplessness. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 1:241-253, 1980Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Schank MJ, Lawrence DM: Young adult women: lifestyle and health locus of control. Journal of Advanced Nursing 18:1235-1241, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar