A Survey of Hospital Practices Related to Pelvic and Rectal Examinations of Psychiatric Inpatients

Abstract

Fifty-three inpatient units in Texas and Massachusetts—15 freestanding psychiatric hospitals and 38 units of general hospitals—responded to a survey to determine current practice in conducting pelvic and rectal examinations of psychiatric patients. Pelvic examinations were never done at 15 of the facilities (28 percent), and rectal examinations were never done at 12 (23 percent). The other facilities did these examinations selectively based on patients' clinical history. Because selective use of these examinations is consistent with recommendations of the American Psychiatric Association and because hospitals that conduct examination selectively have received approval by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, it appears that selective rather than routine pelvic and rectal examinations are now considered reasonable practice.

Psychiatric patients admitted to hospitals are expected to be given a physical examination. A frequent charting defect noted by reviewers from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) is the absence of documentation in patients' records of pelvic and rectal examinations. This portion of the physical examination is often listed as "deferred" or "refused." However, JCAHO reviewers point out that additional attempts should be made to complete these examinations, or the record should justify why such attempts are not made.

A review of the literature for the years 1970 to 1993 on this topic found that no papers had been published during the past five years. Few of the papers published more than five years ago addressed the specific question of the benefits of providing pelvic and rectal examinations to psychiatric patients, especially in acute freestanding hospitals with short stays and a rather young group of patients.

Assessment of physical illnesses among psychiatric patients has focused largely on the role these illnesses play in exacerbating or causing psychiatric disorders. The prevalence of such assessments among psychiatric patients varies considerably, depending on the setting— inpatient or outpatient— and the type of screening used; it especially depends on the opinions of the examining physicians that by remedying the physical illness, the psychiatric disorder might be ameliorated. Much of the older literature on this approach has been summarized in a previous review (1).

In one typical study an effort was made to determine the prevalence of medical disorders in a cross-sectional sample of psychiatric patients housed in 25 California county-operated mental health programs and a state hospital (2). Among 509 patients evaluated, 200 (39 percent) had at least an active physical disease. Only two instances of unspecified gynecological abnormalities were reported. From this study, investigators developed an algorithm using combinations of laboratory tests and physical findings to reduce the chances of not detecting physical illnesses to a suitably low level (2). Personal communication with the lead author revealed that neither pelvic nor rectal examinations were done during that survey.

In surveys we found that reported on the general health of women psychiatric patients, the question of whether routine pelvic or rectal examinations were done was not clear. Thus it is difficult to judge what the diagnostic yield of such examinations would have been. A few surveys were reported that specifically looked for gynecological problems among psychiatric patients. The most extensive covered the period between 1958 and 1964, during which time slightly more than 14,000 women were examined (3). However, this study was done during the days of long-term inpatient stays and is not pertinent to current practices.

A survey of psychiatrists' practices relating to physical examinations was conducted in Rochester, New York, in 1976 (4). The 204 respondents were faculty members and residents at the Rochester Psychiatric Center. Thirteen percent of the faculty members examined inpatients, but only 8 percent examined outpatients. Examinations were purposely omitted by 32 percent of the faculty. Among faculty members who were out of residency for more than five years, this figure rose to 43 percent. The usual reason given for omitting examinations was that patients had been examined by other practitioners.

That pelvic and rectal examinations have been purposely neglected among psychiatric patients— and still are— is unquestionable. No doubt the neglect is due to the perception of many psychiatrists and hospitals that providing psychiatric care is not the same as providing primary care. In fact, psychiatry is not recognized as a primary care specialty by current health care coverage programs, despite past efforts by the American Psychiatric Association to obtain such recognition. Ambiguity about whether psychiatry is a type of primary care is manifested by the great uncertainty among psychiatrists (not to mention residents just out of medical school) about their ability to do an adequate pelvic-rectal examination.

This paper describes a survey of inpatient psychiatric facilities to determine their practices in providing pelvic and rectal examinations.

Methods

To determine current practices related to pelvic and rectal examination of psychiatric patients, we sent a simple questionnaire to 200 psychiatric inpatient facilities, 130 in Texas and 70 in Massachusetts. The eight-item questionnaire was mailed in May 1998. Responses were anonymous.

Results

Replies were received from only 53 of the 200 inpatient psychiatric facilities, for a response rate of 27 percent. Respondents included 15 freestanding psychiatric hospitals and 38 units of general hospitals. Despite this low response rate, there was no reason to believe that the responses were skewed. Thus we consider the survey responses to be a reliable reflection of current practice.

The 15 freestanding facilities reported an average daily census of 35; for the general hospital units this figure was 15. The average number of women in the daily census was 18 for the freestanding hospitals and eight for the general hospital units.

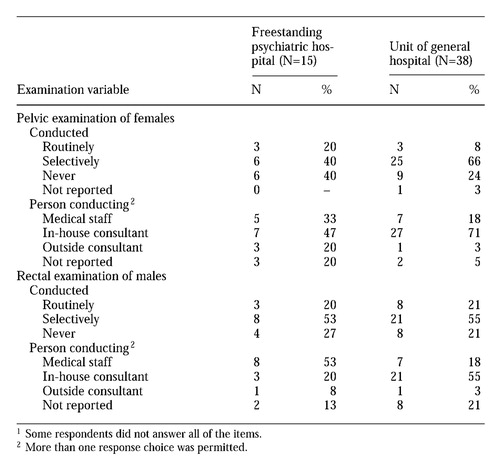

As Table 1 shows, pelvic examinations were never done at 15 of the facilities (28 percent). At six facilities (11 percent) this type of examination was routinely done, and at 31 facilities (58 percent) it was selectively done based on clinical history. The general hospital units were much more likely to use in-house consultants to do these examinations, presumably because of the availability of gynecologic clinics. The freestanding psychiatric hospitals were more likely to rely on in-house staff, whose qualifications were not specified.

Among male patients, rectal examinations were not done in 12 facilities (23 percent). This type of examination was done routinely among male patients at 11 facilities (21 percent) and selectively at 29 facilities (56 percent). As with pelvic examinations, the freestanding psychiatric hospitals had to rely more heavily on medical staff to accomplish rectal examinations, while the units affiliated with general hospitals had easier access to in-house consultants.

Even though some facilities never conducted pelvic and rectal examinations and others did so only selectively, it is notable that only three facilities reported any difficulty with examiners from JCAHO in relation to these examinations. Whether this failure to experience problems represents a more relaxed attitude of the JCAHO or of individual JCAHO reviewers could not be determined from the survey data

Discussion and conclusions

By chance, just as our own hospital's ad hoc committee had begun its deliberations on the subject of pelvic and rectal examinations for psychiatric inpatients, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) published practice guidelines for the evaluation of psychiatric patients (5). In describing the physical examination, no specific mention is made of pelvic or rectal examinations. Rather, the guidelines suggest that an examination should be made of "any body area or organ specifically mentioned in the present illness or review of systems." Furthermore, our literature review offered precious little in the way of justification for routine examinations by psychiatrists.

Selective rather than routine pelvic and rectal examinations for psychiatric inpatients seem to be reasonable medical practice. If such examinations are urgently indicated— for example, if there is bleeding or other signs— referral should be made while the patient is still hospitalized. In nonemergency situations when further examination is indicated, postdischarge referral should be made for such examinations either through the patient's primary care physician or directly to the appropriate clinic. If such policies are followed, the problem of pelvic and rectal examinations for psychiatric patients will no longer be vexing.

The authors are faculty members in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Texas-Houston Medical School. Dr. Varner is professor of psychiatry and medical director of the Harris County Psychiatric Center, 2800 South MacGregor Way, Houston, Texas 77021 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Hollister is professor emeritus of psychiatry and former research medical director of the center.

|

Table 1. Responses by 52 psychiatric facilities to a mailed survey about pelvic and rectal examinations of psychiatric inpatients1

1. Hall RCW, Beresford TP: Physical illness in psychiatric patients: areas of inquiry. Psychiatric Medicine 2:401-415, 1985Google Scholar

2. Sox HC Jr, Koran LM, Sox CH, et al: A medical algorithm for detecting physical disease in psychiatric patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1270-1276, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

3. McBurney RD: Gynecological care at a state hospital for the mentally ill. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 95:345-349, 1988Google Scholar

4. McIntyre JS, Romano J: Is there a stethoscope in the house (and is it used)? Archives of General Psychiatry 34:1147-1151, 1977Google Scholar

5. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for psychiatric evaluation of adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 152(Nov suppl):1-80, 1995Google Scholar