Symptoms Predicting Inpatient Service Use Among Patients With Bipolar Affective Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Symptoms that were risk factors for hospital readmission among psychiatric inpatients diagnosed as having bipolar affective disorder were evaluated. METHODS: Subjects were 100 persons consecutively admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit at a university-affiliated hospital who met Research Diagnostic Criteria for bipolar I or II disorder or schizoaffective disorder, manic type. Patients were assessed using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) within one week of discharge, and their hospitalization status was documented by monthly phone contacts over a period of 15 months. RESULTS: Twenty-four patients (24 percent) were rehospitalized within six months of discharge, and 44 (44 percent) were readmitted within 15 months. Survival analysis using the Cox proportional hazard regression model demonstrated that patients with high scores on a BPRS-derived mania factor were at significantly decreased risk of rehospitalization, whereas those scoring high on a factor consistent with neurovegetative depression were at significantly increased risk. A greater number of previous psychiatric admissions and younger age were also associated with significantly increased risk of rehospitalization. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that patients with bipolar disorder presenting with a depressive episode characterized by prominent neurovegetative features should be treated more aggressively with both pharmacotherapy and intensive outpatient services to reduce the relatively high risk of rehospitalization that appears to be associated with this type of depression.

Studies aimed at identifying risk factors for early or frequent readmission of persons with chronic mental illness to psychiatric hospitals have focused on patients' behavior, sociodemographic characteristics, and previous use of mental health services. Behaviorally, poorer treatment compliance (1,2,3) and aggressive behavior (4,5,6) increase the likelihood of readmission. Lower socioeconomic status and financial problems (7,8), older age (9,10,11), single marital status (8,10), and female gender (2,7,8) are sociodemographic factors that increase the risk of rehospitalization. A greater number of previous psychiatric admissions also increases the risk (1,9,12,13,14), as does a shorter length of stay (13,15).

Recent investigations have also demonstrated that both the degree and type of symptoms that characterize the presenting episode of illness are associated with the likelihood of rehospitalization. For example, Lyons and associates (16) reported that patients readmitted within six months of discharge had higher global levels of symptom severity at the outset of the previous admission. Similarly, Swett (12) found that higher scores just before discharge on the thought disorder factor of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and on the BPRS self-neglect item predicted readmission within 30 days of discharge.

Studies have also found that comorbid disorders or problems, including substance use disorders or substance-related problems (3,17,18) and sexual and impulse control problems (8), increase the likelihood of readmission. By contrast, primary psychiatric diagnosis has generally not been a significant predictor of readmission (17,18).

Because identification of specific symptom constellations that place patients at risk for rehospitalization might better inform clinicians' choice of treatment and disposition, studies of symptoms that are predictors of rehospitalization are of particular relevance for mental health service providers.

Most studies assessing the relationship of symptoms or diagnosis to risk of rehospitalization have been conducted in mixed-diagnosis samples. Although use of diagnostically heterogeneous samples sheds light on the chronic mentally ill population in general, use of such samples might obscure factors predictive of rehospitalization in a single-diagnosis group, resulting in a type II error. This limitation may be particularly applicable to the investigation of clinical or symptom predictors of readmission.

Although some studies have focused on readmission of patients with schizophrenia (9), to our knowledge symptom risk factors for readmission in a sample of patients with research-diagnosed bipolar affective disorder have not been investigated. Because studies of high users of inpatient psychiatric services have shown that bipolar affective disorder is overrepresented among recidivist samples (19), identification of symptom risk factors for rehospitalization of patients with this diagnosis could have important social and economic, as well as clinical, ramifications.

Evidence from two different lines of research on the course of illness in bipolar affective disorder suggests that symptoms of the illness may influence rehospitalization. First, researchers have found a differential course of illness for diagnostic subgroups within the bipolar spectrum. Most relevant, in the Collaborative Study of Depression conducted by the National Institute of Mental Health, patients with bipolar I disorder were more likely to be rehospitalized during the follow-up period than patients with bipolar II disorder (20). Second, the different types of episodes— manic or depressed— have been associated with differing rates or degree of recovery, with most studies finding that patients recover more slowly or less fully from depression than from mania or hypomania (21,22).

To study the impact of symptom presentation on subsequent psychiatric hospitalization, we assessed psychiatric inpatients with bipolar affective disorder that had been diagnosed based on Research Diagnostic Criteria, and we followed their hospitalization status prospectively for a period of 15 months after discharge. Based on the results of previous studies, we hypothesized that the nature of symptom presentation at hospital discharge would predict the likelihood of rehospitalization over the 15-month follow-up period.

Methods

Subjects

The study sample consisted of 147 subjects consecutively admitted to an acute psychiatric inpatient service who were age 16 or older and who met Research Diagnostic Criteria (23) for several disorders. These disorders were bipolar depression with mania (bipolar I disorder), hypomania (bipolar II disorder), or schizoaffective disorder, manic type, based on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) (24). Because the study reported here was carried out as part of a study on family burden in bipolar illness (25), only patients whose family members consented to the large study were included.

Patients were enrolled in the study between October 1993 and September 1995, and follow-up data were collected for 15 months after discharge (approximately through December 1996). A total of 100 persons completed the 15-month follow-up, and this group was the sample in the study reported here.

The 32 percent attrition rate is equivalent to the 32 percent rate observed for the Collaborative Study for Depression (26). Comparison of the 100 subjects who completed the study and the 47 noncompleters did not reveal any significant differences in baseline sociodemographic and clinical variables.

Measures

Within one week of discharge, patients were assessed on diagnostic measures using the SADS-L. In addition, the expanded version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (27), which was developed by Lukoff and colleagues (28) to incorporate the psychotic and affective symptoms associated with bipolar disorder, was used to rate symptom type and severity. The 24-item instrument uses a 7-point scale and is administered by patient interview. An intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated for the four raters based on two videotaped interviews, using all 24 scales. Coefficients for tape 1 were .83, .82, .85, and .96; for tape 2, coefficients were .88, .87, 1, and .90. Internal consistency for the BPRS was acceptable (Cronbach's alpha=.76).

Data on the number and timing of previous psychiatric inpatient admissions were obtained from the SADS-L interview. Data on months of community tenure and on psychiatric rehospitalization were collected over 15 months of follow-up by monthly phone or in-person contact with patients. When patients were not available, the contact was with a family member.

Analyses

The frequency and rate of subsequent psychiatric readmissions for the sample as a whole were calculated. A principal components analysis was performed on the 24-item BPRS data for purposes of data reduction. Although the BPRS has previously been factor analyzed, past studies either employed the original 18-item scale or used a general sample of severely mentally ill persons (29,30) and the results were thus not suited to the aims of this investigation.

Survival analysis using the Cox proportional hazard regression model (31) was employed to describe the relationship between all predictor variables (the BPRS symptom factors and other covariates) and time to rehospitalization over the 15-month follow-up period. This method allowed us to use all available data, including censored observations (that is, data for patients who were not hospitalized during the 15 months). Time to rehospitalization was measured in number of months from the month of the index discharge until the month of the initial rehospitalization.

In this study, a hospital readmission was the outcome variable of interest, and a community stay without readmission for the 15-month study period was a censored event. Hospital readmissions occurring before day 25 within the month of discharge were considered to be equal to a half-month. Preliminary bivariate analyses were conducted using the Pearson r product-moment correlation coefficient to help select variables for the model.

To maximize power, we limited our model to include the four BPRS factors, sociodemographic variables (age, gender, socioeconomic status [32], and living or not living with the identified family caregiver [25]), the total number of previous psychiatric hospitalizations, and whether or not the index episode met SADS-L criteria for major depression or mania versus minor depression or hypomania. The latter variable was included to control for the overall level of psychopathology—that is, to ensure that an observed effect of one or more of the specific BPRS factors was not simply a reflection of the patients' overall severity of illness.

Two additional SADS-L variables, a diagnostic variable that classified patients as schizoaffective, manic type, versus all others SADS-L diagnoses and a variable that classified the index episode as either mania or hypomania versus major or minor depression (pole of index episode), were not significantly associated with the dependent variable at the bivariate level and thus were not included in the model. Similarly, the BPRS total score was not significantly associated with the dependent variable and was not included in the model. Because we were interested in evaluating the contribution of the four BPRS factors while controlling for the effects of sociodemographic variables and overall level of psychopathology, all covariates were entered simultaneously. SPSS software programs (33) were used to perform the analyses.

Results

Sample characteristics

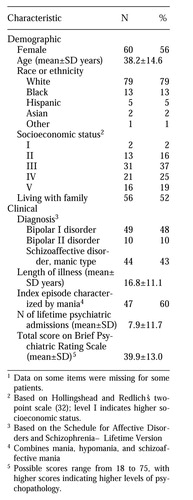

Characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. As a group, subjects were representative of the more chronic end of the bipolar spectrum, having been hospitalized on average almost twice a year during their 16.8 years of illness. Patients of both genders, those with manic as well as depressive index episode poles, and those with schizoaffective disorder as well as bipolar I or II subdiagnoses were well represented in the sample. Most patients were Caucasian and middle class and lived with one or more family members. Age was well distributed in the study sample.

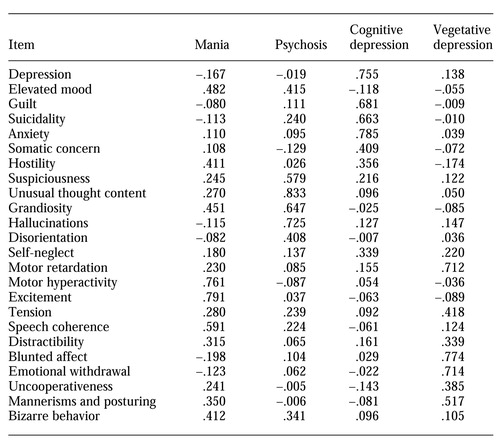

BPRS factor analysis

The principal components analysis yielded four factors accounting for a cumulative variance of 46 percent. As shown in Table 2, factor 1, mania, had high loadings (>.45) on excitement, motor hyperactivity, speech coherence, and elevated mood. Factor 2, psychosis, had high loadings on unusual thought content, hallucinations, grandiosity, and suspiciousness. Two depression factors were found. Factor 3, cognitive depression, had high loadings on anxiety, depressed mood, guilt, and suicidality, and factor 4, vegetative depression, had high loadings on blunted affect, motor retardation, and emotional withdrawal.

Rehospitalization

Forty-four of the 100 patients in the sample had at least one psychiatric hospital admission during the 15 months of follow-up, and 56 stayed in the community without rehospitalization. Of the patients who were rehospitalized, 15, or 34 percent, were admitted within the first three months of the study; 24, or 55 percent, were admitted within the first six months; and 39, or 89 percent, were admitted within the first year.

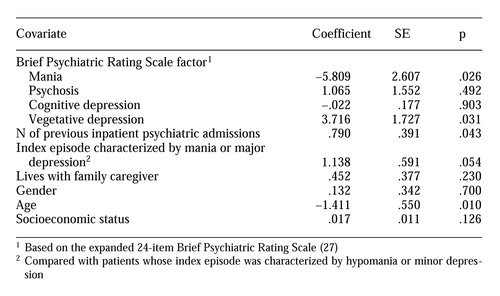

Overall, the variables in the model were highly effective at predicting rehospitalization (χ2=31.32, df=10, p<.001). Table 3 presents the regression coefficients for the predictor variables in the model and related statistics. Older patients and those with manic symptom profiles had a significantly higher probability of not being rehospitalized over the 15 months, while patients with symptom profiles consistent with neurovegetative depression and a greater number of previous psychiatric admissions were at significantly greater risk for rehospitalization. Patients whose index episode met criteria for a major affective episode of any type (major depression, mania, or schizoaffective disorder) were at marginally greater risk for rehospitalization (p<.06) than patients whose index episode met criteria for hypomania or minor depression. These effects were independent of one another.

By contrast, psychotic symptomatology and a more cognitively characterized depressive symptom pattern were not significant predictors of time to rehospitalization. Patient gender, socioeconomic status, and living situation (living or not living with the family caregiver) were also not significantly associated in this model with rehospitalization.

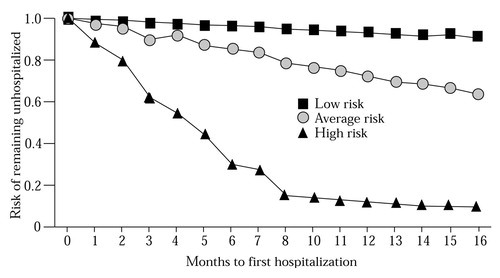

Figure 1 plots the probability of remaining unhospitalized as a function of the number of months postdischarge for a patient at average risk of rehospitalization (mean of covariates) and at high and low risk of rehospitalization. High and low risk patterns were generated by assigning values one standard deviation above and below the mean of each covariate with a p value of less than .06 while assigning the mean value to all other covariates in the model.

Because just over half (55 percent) of the sample members were rehospitalized at six months, this interval offers a useful point of comparison. Compared with a patient at average risk of rehospitalization, who has an .85 probability of remaining unhospitalized at six months, a patient at high risk has a probability of remaining unhospitalized of only .30. A patient at low risk has a probability of remaining unhospitalized at six months of .98.

Discussion

Rate and model of rehospitalization

Forty-four percent of the sample of 100 patients who met Research Diagnostic Criteria for bipolar I or II disorder or schizoaffective disorder, manic type, were rehospitalized within 15 months of discharge. This rate is consistent with the results of previous investigations of rehospitalization among patients with bipolar disorder, which reported 12- and 18-month rates of rehospitalization ranging between 58 percent and 60 percent (34,35,36).

The Cox regression model was highly effective in identifying patient characteristics predictive of residing in the community without rehospitalization. A change in value of the significant covariates in the model of just one standard deviation around the mean produced a spread in the probability of a patient's remaining unhospitalized that was greater than 50 percent.

Predictors of time until rehospitalization

We hypothesized that the nature of symptom presentation at discharge would predict time until rehospitalization. The results of this study demonstrate that symptom profiles consistent with mania significantly decreased the likelihood of rehospitalization in the 15 months after discharge, whereas those consistent with a neurovegetative type of depression significantly increased the likelihood. By contrast, symptom profiles consistent with psychosis and a more cognitively characterized depression did not significantly alter the risk of rehospitalization during this time frame.

One possible explanation for these findings is simply that the BPRS mania factor is elevated primarily among patients with less severe forms of the illness (hypomania or bipolar II disorder), while the vegetative depression factor taps into a more severe form of the illness (schizoaffective disorder). However, the mania factor was not significantly associated with whether a patient's index episode was major (manic) or minor (hypomanic). Moreover, it was significantly, although modestly, associated with having a lifetime diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder (r=.175, df=141, p=.036). Thus its protective effect is not likely to be explained by an association with a milder form of illness.

Similarly, because the vegetative depression factor was not significantly associated with a lifetime diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, the increased risk of rehospitalization among patients' scoring high on this factor does not appear to reflect the presence of the negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia. Although the vegetative depression factor was marginally and positively associated with having an index episode characterized by major depression (r=.160, df=141, p=.056), it was still significant in the multivariate analysis, which controlled for this association. Thus we do not believe that the predictive power of the mania factor and the vegetative depression factor can be explained as purely a function of their association with severity of illness.

It is of interest that in contrast to the BPRS symptom factors, the SADS-L variables—a lifetime diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder versus bipolar I or II disorder and the polarity of the index episode—were not significantly associated with time until rehospitalization. The relatively low predictive utility of the SADS-L variables may reflect the challenges posed by diagnostic classification in bipolar illness, which is complicated by the occurrence of mixed states as well as by problems in determining the presence of schizoaffective symptoms (37,38,39). Our results from the BPRS factor analysis suggest that even within one pole—for example, the depressive pole—different subtypes exist that may further complicate, and potentially help refine, the prediction of outcomes such as rehospitalization.

In light of this complexity, scaling patients' symptoms along multiple dimensions—manic, depressive, and psychotic—may represent a more useful approach, at least to the prediction of rehospitalization. A logical extension of the findings reported here would be to use the symptom factor data in conjunction with cluster analytic methods to identify subgroups of patients at high and low risk for rehospitalization. Identification of such subgroups would enable clinicians to implement more strategic, symptom-targeted pharmacotherapies for patients with bipolar illness, such as the use of maintenance antidepressant medication or concomitant atypical neuroleptics. Identification of symptom subgroups of patients at high risk for rehospitalization might also provide a rationale for use of intensive outpatient treatment, such as day treatment, for more patients with bipolar illness or for use of multiple treatment modalities, such as combining family with individual or group treatment.

Based on a retrospective case analysis of 100 consecutive readmissions to a psychiatric inpatient unit, Talbott (6) concluded that 40 readmissions might have been prevented by more intensive staff involvement with the patient or the patient's family. Although use of intensive outpatient mental health services is generally based on the overall severity of patients' illness, these data indicate that the presence of a neurovegetative depression may provide a better rationale for use of intensive treatment, because overall symptom severity as assessed by the BPRS total score was not significantly associated with time until rehospitalization. These data suggest that in the short term, patients presenting with a depressive episode characterized by prominent neurovegetative features should be treated more aggressively with both pharmacotherapy and intensive outpatient services to reduce the relatively high risk of rehospitalization that appears to be associated with this type of depression.

In contrast to previous investigations, our study did not find that female gender, lower socioeconomic status, or older age was significantly associated with increased risk of rehospitalization; in fact, in our study older age had a protective effect. These discrepancies are likely due partly to differences in patient samples, because the previous investigations mainly examined samples of patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia, in which, for example, the distribution of socioeconomic levels is more often skewed toward the lower end.

Interestingly, the association of age and time until rehospitalization, although positive at the bivariate level (r=.290, df=41, p=.057), was negative when the analysis controlled for the effects of illness chronicity (the number of previous psychiatric inpatient admissions) on age in the multivariate context (r=−.170, df=130, p=.052). Other studies reporting that the risk of rehospitalization increases with age have not uniformly partialled out the effects of chronicity of illness on the association between age and rehospitalization.

These findings raise additional research questions that cannot be answered within the limitations of the design of our study. First, information about the clinical course and treatment of the patients over the 15-month follow-up is needed to identify variables that may mediate or moderate the associations of the symptom factors with time until rehospitalization. For example, it is not clear whether the association of the vegetative depression factor with rehospitalization is mediated by an association of vegetative depression with relapse, or whether high scores on this factor may have defined a subgroup of patients who did not fully recover from their depressive index episode.

Incorporation into our model of such constructs as the adequacy of the prescribed pharmacotherapy, patients' treatment compliance, attitudes toward illness of patients' family members, and the help provided by patients' support networks may help explain the findings. For example, it is possible that the apparent protective effect of mania is related to the availability and use of more effective treatments for mania than for depression.

Second, although the expanded version of the BPRS (28) has become a standard instrument in studies of treatment and outcome in bipolar affective disorder (40,41), its use here limits comparison of our findings with studies of unipolar affective disorder, for which the Hamilton Rating Scale (42) is used almost exclusively. Research on unipolar depression has established that patients with different types of depression (mild or severe) respond differentially to the same treatment regimen (43), and it would be useful to compare the two BPRS depression factors identified in this study with other, established classification schemas for depression.

A third research question raised by the findings is that the stability of the factor scores for individual patients must be evaluated over time to determine whether the BPRS factors are measuring trait- or state-dependent attributes. Because state- and trait-dependent types of depression may respond differentially to somatic and psychotherapeutic interventions (44), this information has clinical relevance.

Fourth, the generalizability of the findings is limited to inpatients. In addition, although we found no significant differences in baseline demographic or clinical variables between the study sample and the patients who did not complete the 15 months of follow-up, the noncompleters may have differed in other respects not measured. Future research should attempt to replicate these findings in an outpatient sample, incorporate symptom measures specific to mania and depression, and examine treatment variables and intermediary outcome variables that may help explain the associations observed between symptoms at discharge from the hospital and the likelihood of rehospitalization over the next 15 months.

Acknowledgment

This paper was supported by grant MH-51348 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Perlick and Dr. Rosenheck are affiliated with the Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the West Haven Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516. Dr. Perlick is also affiliated with the department of psychiatry and Dr. Rosenheck with the departments of psychiatry and epidemiology and public health at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Clarkin, Dr. Sirey, and Dr. Raue are with New York Hospital-Westchester Division and the department of psychiatry at Weill Medical College of Cornell University in White Plains, New York.

Figure 1. Probability of remaining unhospitalized among low-, average-, and high-risk patients with bipolar disorder during 15 months after hospital discharge

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 100 inpatients with bipolar disorder followed for 15 months after hospital discharge1

|

Table 2. Loadings on four factors resulting from a factor analysis of the expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale

|

Table 3. Results of Cox regression analysis of time to rehospitalization among 100 patients with bipolar disorder

1. Davis EB, Egri G, Caton CLM: Outcomes of care systems for chronic patients. Journal of the National Medical Association 76:67-73, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

2. Casper ES: Identifying multiple recidivists in a state hospital population. Psychiatric Services 46:1074-1075, 1995Link, Google Scholar

3. Green JH: Frequent rehospitalization and noncompliance with treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:963-966, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Holmes W, Solomon P: Organizational and client influences on psychiatric admission. Psychiatry 44:201-209, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA et al: Characteristic hostility in schizophrenic outpatients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:163-170, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Talbott JA: Stopping the revolving door: a study of readmissions to a state hospital. Psychiatric Quarterly 48:159-168, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Gruber JE: Paths and gates: the sources of recidivism and length of stay on a psychiatric ward. Medical Care 20:1197-1208, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Polk-Walker GC, Chan W, Meltzer AA, et al: Psychiatric recidivism prediction factors. Western Journal of Nursing Research 15:163-176, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hoffman H: Age and other factors relevant to the rehospitalization of schizophrenic outpatients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:205-210, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rabinowitz J, Mark M, Popper M, et al: Predicting revolving-door patients in a 9-year national sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 30:65-72, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Horowitz A: The pathways into psychiatric treatment: some differences between men and women. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 18:169-178, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Swett C: Symptom severity and number of previous psychiatric admissions as predictors of readmission. Psychiatric Services 46:482-485, 1995Link, Google Scholar

13. Appleby L, Desai PN, Luchins DJ, et al: Length of stay and recidivism in schizophrenia: a study of public psychiatric hospital patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:72-76, 1993Link, Google Scholar

14. Rosenblatt A, Mayer JE: The recidivism of mental patients: a review of past studies. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 44:697-706, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Brown GW: Schizophrenia and Social Care: A Comparative Follow-Up Study of 399 Schizophrenic Patients. London, Oxford University Press, 1966Google Scholar

16. Lyons JS, O'Mahoney MT, Miller SI, et al: Predicting readmission to the psychiatric hospital in a managed care environment: implications for quality indicators. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:337-340, 1997Link, Google Scholar

17. Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, et al: Predicting the "revolving door" phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:856-861, 1995Link, Google Scholar

18. Goodpastor WA, Hare BK: Factors associated with multiple readmissions to an urban public psychiatric hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:85-87, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Goldfinger SM, Hopkin JT, Surber RW: Treatment resisters or system resisters? Toward a better service system for acute care recidivists. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 21:17-27, 1984Google Scholar

20. Coryell W, Keller M, Endicott J, et al: Bipolar II illness: course and outcome over a five-year period. Psychological Medicine 19:129-141, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Angst J: The course of major depression, atypical bipolar disorder, and bipolar disorder, in New Results in Depression Research. Edited by Hippius H, Klerman GL, Matussek N. Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1986Google Scholar

22. Endicott J, Nee J, Andreasen N, et al: Bipolar II: combine or keep separate? Journal of Affective Disorders 8:17-28, 1985Google Scholar

23. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:773-782, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:837-844, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Perlick DA, Clarkin JF, Sirey J, et al: Burden experienced by care-givers of persons with bipolar affective disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar

26. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:971-983, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J: Manual for the expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:594-602, 1986Google Scholar

29. Guy W: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacological Research. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976Google Scholar

30. Burger GK, Calsyn RJ, Morse GA, et al: Factor structure of the expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology 53:451-454, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Cox DR: Regression models and life tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 34(series B):187-220, 1972Google Scholar

32. Hollingshead A, Redlich FC: Social Class and Mental Illness: A Community Study. New York, Wiley, 1958Google Scholar

33. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences: Advanced Statistics 7.5. Chicago, SPSS, 1997Google Scholar

34. Dickson WE, Kendell RE: Does maintenance lithium therapy prevent recurrences of mania under ordinary clinical conditions? Psychological Medicine 16:521-530, 1986Google Scholar

35. Strober M, Morrell W, Lampert C, et al: Relapse following discontinuation of lithium maintenance therapy in adolescents with bipolar illness: a naturalistic study. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:457-461, 1990Link, Google Scholar

36. Prien RF, Caffey EM, Klett CJ: Factors associated with treatment success in lithium carbonate prophylaxis: report of Veterans Administration and National Institute of Mental Health collaborative study group. Archives of General Psychiatry 31:189-192, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Akiskal HS, Puzantian VR: Psychotic forms of depression and mania. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2:419-439, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Winokur G, Clayton PJ, Reich T: Manic Depressive Illness. St Louis, Mosby, 1969Google Scholar

39. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

40. Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ, Nuechterlein KH, et al: Expressed emotion, affective style, lithium compliance, and relapse in recent onset mania. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 22:628-632, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

41. Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ, Nuechterlein KH, et al: Family factors and the course of bipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:225-231, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 23:56-62, 1960Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Thase ME, Greenhouse JB, Frank E, et al: Treatment of major depression with psychotherapy or psychotherapy-pharmacotherapy combinations. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1009-1015, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Thase ME, Fasiczka AL, Berman SR, et al: Electroencephalographic sleep profiles before and after cognitive behavior therapy of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:138-144, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar