Relationship Between Maternal Church Attendance and Adolescent Mental Health and Social Functioning

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study compared maternal attendance at religious services with standard demographic characteristics such as race, type of religion, and mother's education in terms of their relative association with the behavioral and social functioning of young adolescents. METHODS: The Child Health and Illness Profile— Adolescent Edition and the Children's Depression Inventory were used to screen 445 youths age 11 through 13 who were randomly selected from two public middle schools in Baltimore. Based on the findings, the investigators selected a sample of 143 youths in which approximately two-thirds were at risk of having a psychiatric disorder and the remaining third were unlikely to have a psychiatric disorder. The youths and their mothers were interviewed at home to determine the mothers' frequency of participation in religious services and the youths' self-reported health and mental health status and social role functioning. RESULTS: Youths whose mothers attended religious services at least once a week had greater overall satisfaction with their lives, more involvement with their families, and better skills in solving health-related problems and felt greater support from friends compared with youths whose mothers had lower levels of participation in religious services. Maternal attendance at religious services had a strong association with the youths' outcome in overall satisfaction with health and perceived social support from friends, although family income was the strongest predictor of five other aspects of functioning, including academic performance. CONCLUSIONS: Frequent maternal participation in religious services was associated with healthy functioning and well-being in this sample of young adolescents. This association is as important as or more important than associations involving other traditional demographic variables, with the exception of family income.

The role of protective influences in the lives of adolescents is increasingly of interest to clinicians and the general community. Family and cultural norms and activities are gaining acceptance as critical influences in the development of competent and resilient youth (1,2). Despite the recognition that family routines and values are crucial to children's development, psychiatric research has rarely addressed the contribution of parental religious activities to children's mental health and social competence.

Other factors such as family income, parental marital status, family composition, and the child's gender are accepted as robust influences on the mental health of youth (3,4,5,6,7,8). Sociodemographic factors such as family structure have been shown to be risk factors for morbidity, behavior problems, school failure, and other negative outcomes among youth (9,10,11), but these factors are likely to be markers for complex mechanisms that influence child development.

We were interested in the possibility that level of participation in religious activities by mothers and adolescents may also be a useful indicator of child functioning and mental health outcomes. Religious activities have been shown to be a stable family sociodemographic characteristic. Gallup surveys done between 1939 and 1995 found that between 37 and 47 percent of adult Americans had attended church or synagogue in the seven days before the interview; however, between 1975 and 1995, the range was between 40 and 43 percent (12).

Longitudinal studies of child and adolescent development have suggested that infrequent church attendance by family members is related to unstable family patterns and is predictive of early sexual activity, teenage pregnancy, substance use and abuse, and delinquency among adolescents (13). In an urban population of African-American adolescents, the development of substance abuse was linked to low levels of church attendance by family members (14).

The study reported here examined the relationship between frequency of church attendance by mothers and the presence of positive self-concept and prosocial behaviors among young adolescents age 11 to 13. The study focused on two questions. First, what influence does maternal participation in religious activities have on young adolescents' symptomatology and social functioning? Second, how does the influence of maternal religious participation compare with that of standard demographic variables in the strength of association with variables measuring symptoms and social functioning among young adolescents?

Religious beliefs and attitudes were not assessed. Consequently, no inference can be made about the relationship between attendance at church or temple services and religious commitment.

Methods

In the initial stage of the research, a representative sample of urban adolescents in public middle schools was recruited and screened to identify a subsample that included youths at high risk for psychiatric disorders and a comparison group of youths at low risk for psychiatric disorders. In the second stage of the research, this subsample of youths and their mothers were interviewed at home by trained interviewers who inquired about the families' sociodemographic characteristics and the mental health characteristics and social role functioning of the youths.

This work was part of a larger study of social role functioning and need for mental health services among adolescents (15). The youths were assessed in the middle schools in October 1993, and the home interviews were conducted over the subsequent eight months.

Procedures

Setting.

Youths were recruited from two of the 32 public middle schools in Baltimore, Maryland. One middle school served predominantly working-class neighborhoods; 60 percent of the students were white. The other middle school served middle- and lower-income neighborhoods; 85 percent of the students were African American.

Representative school sample.

In both middle schools approximately 100 students were randomly selected from the class lists of grades six, seven, and eight. Parents were asked to provide written informed consent through the mail, and adolescents gave written consent in school. Consent allowed the completion of an in-school survey of health and functioning of the adolescent, a survey by telephone of the mother or mother surrogate, a home interview involving both the adolescent and the mother, and a one-year follow-up of the child. To be eligible for the study, adolescents had to have lived with their mother or mother surrogate at least 50 percent of the time during the past year. Respondents had to complete the interview in English.

A total of 604 students met eligibility criteria. Of those, 445, or 74 percent, completed the in-school survey. The 26 percent who did not complete the survey included 140 students whose parents refused to participate in the longitudinal study, five students who refused to participate, and 14 students whose parents could not be contacted. The in-school health survey was introduced, distributed, and collected by trained research assistants while the teachers were in the classrooms. The confidentiality of the survey responses was carefully maintained.

The mothers of all students with a completed health survey were called by trained research assistants and asked to complete a questionnaire about their child's behavior. Telephone surveys were completed by 85 percent of the mothers of youths who had completed an in-school health survey.

Stage-two sample.

A second sample of 143 adolescents and their mothers or surrogate mothers was selected from the 378 youths for whom both the health survey and the phone survey with the mother were available. Youths were selected in a stratified manner based on their school, grade in school, race (white, African American, or other), and scores on screening measures for psychiatric disorder, which are described below.

The threshold for determining risk for psychiatric disorder was set as one standard deviation above the median on any of the screening measures. Separate cutoff points were calculated for girls and boys. This process typically identified a group that was above the 80th percentile in severity of symptoms.

Two-thirds of the final sample was selected from the group assessed to be at risk of having a psychiatric disorder. The remaining third of the final sample was selected from among the youths who did not appear to be at risk of psychiatric disorder based on any of the screening measures.

Sixty-six percent of the youths were African American, and 31.2 percent were white. The remaining 2.8 percent included American Indians, Hispanics, youths of other ethnic groups, and biracial youths. The youths were from families of low and middle economic status, similar to the overall population of adolescents in Baltimore public schools.

Trained research assistants conducted the in-home interviews with the youths and their mothers, which took about two hours. In each household, the youth and the mother were interviewed at the same time by different interviewers in separate locations in the home.

Measures

Four scales, two completed by the adolescent in school and two by the mother in the telephone interview, were used to screen the youths into the second-stage sample. The youths reported on two scales of emotional distress— the Child Health and Illness Profile— Adolescent Edition and the Children's Depression Inventory. Based on evidence that parents' reports of problem behaviors are more accurate than adolescents' self-reports (16,17), mothers were asked to report on their children's problem behaviors. This information was provided through mothers' responses to the aggression and delinquency subscales of the Child Behavior Checklist.

Child Health and Illness Profile.

The Child Health and Illness Profile— Adolescent Edition is a comprehensive, reliable, and valid self-assessment of adolescent health (18). The subdomain of emotional discomfort was used in the screening procedure to assess emotional distress; its internal consistency reliability was good (alpha=.77).

Adolescents also reported on other areas covered by the profile, including overall satisfaction with health, self-esteem, physical discomfort or symptoms, limitations on activities, risk-taking behaviors, negative peer influences, threats to achievement (conduct disorder symptoms), involvement with their family, problem solving in the areas of social and health issues, and academic performance. Internal consistency reliability for these items was good (alpha=.71 to .81), except for academic performance (alpha=.63). Lower reliability for academic performance could be expected because this subscale assessed disciplinary actions as well as academic achievement and school honors.

Children's Depression Inventory.

The Children's Depression Inventory (19) is one of the most widely used measures of depression among youth and has good to excellent internal consistency and test-retest reliability (20), even in use with young adolescents. Internal consistency reliability in this study's sample was good (alpha=.89).

Child Behavior Checklist.

The aggression and delinquency subscales of the Child Behavior Checklist (21) effectively characterize the core aspects of aggressive and delinquent behavior among youth (22). The subscales were used with mothers in the telephone interview to screen for their childrens' behavior problems. Internal consistency reliability for both subscales was good (alpha=.87 for aggression and .71 for delinquency).

In-home interview

Adolescents responded to a questionnaire developed for this study that included questions on life events, delinquent behavior, family support, participation in organized activities, social support from friends, prosocial activities with friends and relatives, and the availability of a support person. They also completed two scales developed by Harter (23) that measure perceived competence in the areas of social acceptance by peers and romantic appeal to peers. The alpha coefficients for all of these scales ranged from. 69 to .80, with the exception of those for social acceptance by peers and romantic appeal to peers, which were .63 and .60, respectively.

As part of the in-home interview, mothers were asked how frequently they went to church or temple. Mothers were considered to have high participation in religious services if they attended services at least once a week, a frequency consistent with the definition of a high level of church service participation in a Gallup survey (8). Mothers who attended religious services less often than once a week, including those who never attended church or temple, were considered to have low participation.

Data on sociodemographic variables were based on information from the child's school survey and from the in-home interview. Six of those variables were tested for their effect on adolescent functioning. They were mother's religion (Protestant or Catholic), the adolescent's gender, race (African American or white), family structure (adolescent lives with biological parents versus all other family structures), mother's education (did not complete high school versus completed high school), and the average annual income per person in the household (greater or less than $5,000 a person a year).

Statistical analyses

T tests and chi square tests were used to compare the demographic characteristics of the mothers with high and low participation in religious services. The significance level for these tests was set at p<.05.

Bivariate analyses using t tests were done to determine the relationship between each of the dichotomous independent sociodemographic variables and the continuous variables measuring adolescents' behavioral and social functioning. Because of the multiple comparisons, a conservative significance value (p<.01) was used to interpret the bivariate analyses.

Subsequently, separate linear regression analyses were done for each of the adolescent outcomes that were significantly predicted at the p<.1 level by any sociodemographic variable. Separate regression models were used to investigate the effect of the variables on each outcome and to reduce the number of missing subjects that would result if multivariate analysis were used. (In multivariate analysis, respondents missing data on even a single variable would be dropped.) A small number of subjects who could not be categorized using the dichotomies for religious preference and racial or ethnic background were not included in those analyses.

In the analysis of demographic predictor variables, mother's education was omitted because its correlation of .54 with family income indicated an unacceptable level of overlap between the two variables. The regression analyses were intended to highlight the independent contribution of each of the sociodemographic variables to each aspect of adolescent health and functioning over and above the collective contribution of the other variables in each of the models.

Results

Among the mothers of the middle school students in the sample, 30.6 percent had high participation in religious services, and 69.4 percent had low participation. The mothers with high participation—those who attended church or temple services at least once a week—had significantly higher income and better education than the group with low participation (t=3.5, df=65, p=.001, and t=2.1, df=127, p=.037, respectively). In addition, the mothers in the high-participation group were more likely to be living with the child's father (t=2.37, df=74, p=.021). No differences between the two groups were found on other factors, such as race, number of individuals in the household, the gender of the youth, and school grade.

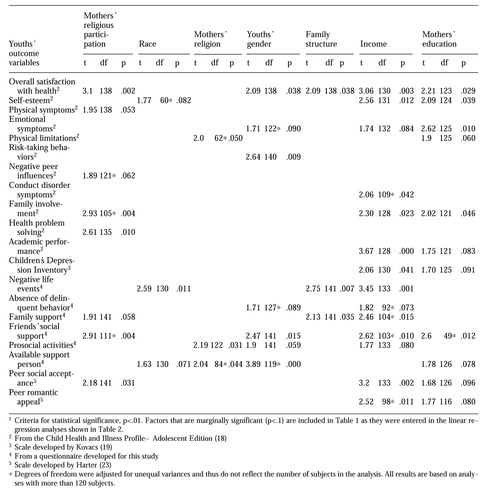

The bivariate analyses summarized in Table 1 show that high participation by mothers in religious services was significantly related to their child's social functioning on four dependent variables. Youths whose mothers were in the high-participation group reported a greater sense of overall satisfaction with their health, experienced greater involvement with their families, evidenced greater skills in solving health-related problems, and felt greater support from friends than children of mothers in the low-participation group.

The other sociodemographic factors were also associated with adolescent outcomes. In the one significant effect for race, white youths had a higher level of negative life events, and they were also marginally lower in self-esteem and marginally more likely to report having a supportive friend. There were no significant effects for type of religion. Boys reported significantly more risk behaviors than did girls, and girls were more likely to report having a supportive person to turn to.

Adolescents living in homes with both biological parents had significantly more negative life events and tended to be more satisfied with their life and experience more family support, compared with those living in homes with a different parenting structure. Youths who lived in families with an income greater than $5,000 per person had better outcomes in almost every variable considered, with the exception that they also had significantly more negative life events. Youths whose mothers had finished high school reported better functioning and well-being compared with youths whose mothers had not finished high school.

To summarize data shown in Table 1 in terms of the number of significant relationships (p<.01) with outcome variables observed for each of the sociodemographic independent variables, there were four for mothers' attendance at religious services, one for race, none for type of religion, two for adolescent gender, one for family structure, seven for income, and two for maternal education. The only sociodemographic characteristic that surpassed mother's religious participation in the number of significant relationships with adolescent outcomes was family income.

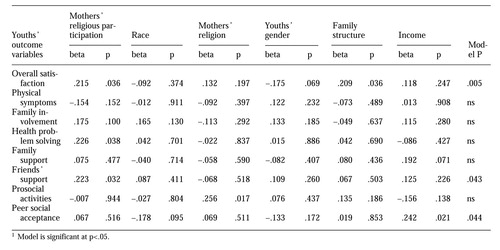

Table 2 summarizes the results of eight separate linear regression analyses, one for each dependent variable for which maternal participation in religious activities was significant in the bivariate analyses at the p<.1 level. The dependent variables are listed in the first column, and the independent sociodemographic variables that were analyzed in every model are shown at the top of subsequent columns. At the far right, the column labeled "model P" shows the overall significance of the multiple linear regression analysis for the full model of all the sociodemographic variables in relation to the specific dependent variable examined. Inferences should be made only for the models significant at the p<.05 level. For each cell in the analysis, the beta coefficient and the probability that the beta is significantly different from zero are shown. The beta demonstrates the strength of the contribution of the particular independent variable to the specific dependent variable while controlling for the contribution of all other independent variables.

Three aspects of social functioning were significantly explained by this model—overall satisfaction with health, support from friends, and peer social acceptance. Mothers' high level of participation in religious services was a significant predictor of adolescents' overall satisfaction with their health; only family structure also made a significant contribution to their satisfaction. Maternal participation in religious services was the only factor significantly associated with perceived social support from friends. Finally, youths' feelings of social acceptance by peers were significantly predicted only by family income.

Discussion

The data suggest that the frequency of maternal church or temple attendance is an important protective factor in the behavioral functioning of middle school youths from age 11 through 13. The results suggest that young teenagers are more likely to be satisfied with their lives when coming from a family where the mother participates in religious services at least once a week and where both parents are living at home. In addition, children are more likely to feel socially supported if they come from a family whose mother attends religious services at least once a week.

Not surprisingly, family income was overall the most powerful predictor of children's well-being and functioning. However, besides that important variable, maternal attendance at church was associated as strongly as or more strongly than the other traditional demographic variables with positive outcomes among these middle school children. This finding adds to the literature that identifies participation in religious activities as an important demographic variable in the study of child and adolescent mental health and illness.

Similar to the other sociodemographic characteristics associated with child mental health, church attendance is likely to be a marker for multiple mechanisms that influence family functioning and child development. It is likely that a third unmeasured factor acts both to increase the frequency of mothers' religious participation and to promote mental health and a sense of well-being among young adolescents. That third factor may be religious faith, but it may also be some other family characteristic such as family orderliness. Other major demographic factors such as maternal education, race, and type of religion did not significantly contribute to positive youth functioning in this study. The main contribution of the study is the identification of an easily assessed, stable parental characteristic that is associated with children's mental health and functioning.

In interpreting these findings, the study's limitations must be kept in mind. The study was done in an urban setting and involved a relatively small sample. However, our finding that 30.6 percent of the mothers attended religious services at least once a week is consistent with earlier reports that 31 percent of a sample of 4,028 adult Americans attended church or synagogue at least once a week (12). One limitation is that the in-school survey was completed by only 71 percent and 77 percent of students in the two schools. Nevertheless, that response rate was quite good for an informed consent procedure with parents, especially a study that called for participation over the course of a year (longitudinal data are not reported here). Nonparticipation was primarily related to the one-year duration of the study. Well-organized and healthy families may have been overrepresented in this sample, and these characteristics may be associated with both religious participation and with positive adolescent outcomes. This possibility is an important issue for future investigation.

It is worth noting that adolescents' reported frequency of their own participation in religious services did not have a significant effect on their functioning. Almost half of the middle school youths (49 percent) reported that they attended church at least once a week, whereas only about a third of their mothers reported this frequency of attendance. It is unclear why the youths reported higher rates of attendance at religious services. A contributing factor may have been that the interview with the mothers allowed for finer distinctions in levels of church attendance, discriminating between attending "every week" and "almost every week." Such distinctions were not available to the youths, whose choices in this range were "every week" and "about every month."

Youths age 11 through 13 years are at a particularly vulnerable and impressionable stage of development. Their emerging mental capabilities allow for more abstract thinking, creativity in problem solving, and awareness of the needs and feelings of others (24,25). This sophisticated cognitive ability gives them greater comprehension of the full emotional impact of real-world problems, which may explain the increased rates of psychiatric problems that emerge in the transition to adolescence.

Clearly, identification of parent or family routines or practices that are associated with better outcomes is important, especially in the challenging circumstances found in the inner city. Participation in religious activities by parents may be one way in which values and positive expectations are communicated to youth. On the other hand, mothers' church attendance may simply be a marker for families in which early adolescents function well. Further research is needed to clarify which interpretation is most informative.

Conclusions

The study results suggest that frequent maternal participation in religious services is associated with positive social functioning and well-being of children at the critical life phase of early adolescence. Furthermore, this association is stronger than that involving other traditional demographic variables with the exception of family income. Surveys of Americans indicate that the percentage of the population that attends religious services has been consistent since the mid-1940s and that the majority of Americans have some affiliation with religion and religious practices (12). Consequently, we suggest that participation in religious activities is an important, relatively stable sociodemographic factor that may be useful in understanding vulnerability and resilience of adolescents in studies of mental and physical health.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of a larger project funded by grant RO1-MH-47903 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Riley. The authors thank Lily Yu for assistance with data analysis.

When this research was done, Dr. Varon was a full-time staff member at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. He is currently medical director of the division of child and adolescent psychiatry at Sinai Hospital of Baltimore, 2401 West Belvedere Avenue, Baltimore, Maryland 21215 (e-mail, [email protected]), and instructor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. Dr. Riley is associate professor in the department of health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health and the department of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

|

Table 1. Bivariate analysis of influence of mothers' participation in religious services and other sociodemographic variables on middle school youths' self-reported well-being and social functioning1

|

Table 2. Multiple linear regression analysis including variables measuring youths' outcomes that were significantly related to maternal religious participation and other sociodemographic variables (p<.1) in bivariate analyses1

1. Nettles SM, Pleck JH: Risk, resilience, and development: the multiple ecologies of black adolescents in the United States, in Stress, Risk, and Resilience in Children and Adolescents: Processes, Mechanisms, and Interventions. Edited by Haggerty LR, Sherrod N, Garmezy N, et al. London, Cambridge University Press, 1994Google Scholar

2. Rutter M: Resilience in the face of adversity: protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 147:598-611, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, et al: Socioeconomic status and health: the challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist 49:15-24, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Alwin DF, Thornton A: Family origins and the schooling process: early versus late influence of parental characteristics. American Sociological Review 49:784-802, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Family income, in The State of America's Children, 1995 Yearbook. Washington, DC, Children's Defense Fund, 1995Google Scholar

6. Feinstein JS: The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: a review of the literature. Milbank Quarterly 71:279-319, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. McLeod JD, Shanahan MJ: Poverty, parenting, and children's mental health. American Sociological Review 58:351-366, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Williams DR: Socioeconomic differentials in health. Social Psychology Quarterly 53:81-99, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Angel R, Worobey JL: Single motherhood and children's health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 29:38-52, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cherlin AJ, Furstenberg FF, Chase-Lansdale L, et al: Longitudinal studies of effects of divorce on children in Great Britain and the United States. Science 252:1386-1389, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Zill N: Behavior, achievement, and health problems among children in stepfamilies: findings from a national survey of child health, in The Impact of Divorce, Single Parenting, and Step-Parenting on Children. Edited by Hetherington EM, Arasteh J. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

12. Princeton Religion Research Center: Religion in America. Princeton, NJ, Trenton Printing, 1996Google Scholar

13. Dryfoos J: Adolescents at Risk. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

14. Oyemade UJ, Washington V: The role of family factors in the primary prevention of substance abuse among high-risk black youth, in Ethnic Issues in Adolescent Menta1 Health. Edited by Stiffman AR, Davis LE. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1990Google Scholar

15. Riley AW, Ensminger ME, Green B, et al: Social role functioning by adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:620-628, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Bird HR, Schwab-Stone M, Andrews H, et al: Global measures of impairment for epidemiologic and clinical use with children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 6:295-307, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Hart EL, Lahey BB, Loeber R, et al: Criterion validity of informants in the diagnosis of disruptive behavior disorders in children: a preliminary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:410-414, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Starfield B, Riley AW, Green BF, et al: The Adolescent Child Health and Illness Profile: a population-based measure of health. Medical Care 33:553-556, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kovacs M: The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacology Bulletin 21:995-998, 1985Medline, Google Scholar

20. Kazdin AE: Childhood depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 31:121-160, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Achenbach T: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

22. Achenbach T, Conners CK, Quay HC, et al: Replication of empirically derived syndromes as a basis for taxonomy of child/ adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 17:299-323, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Harter S: The Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents. Denver, University of Denver Press, 1988Google Scholar

24. Offer D, Schonert-Reichl A: Debunking the myths of adolescence: findings from recent research. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 31:1003-1014, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Lapsley DK: Continuity and discontinuity in adolescent social and cognitive development, in From Childhood to Adolescence: A Transitional Period? Edited by Montemayor R, Adams GR, Gullotta TP. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1990Google Scholar