Case Managers' and Clients' Perspectives on a Representative Payee Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Clients with severe and persistent mental illnesses often require a representative payee to help manage benefit funds. This study compared the perceptions of clients and clinical case managers about the benefits of and problems with the representative payee relationship. METHODS: Fifty-four clients receiving assertive community treatment completed an interview that assessed satisfaction with their experience of having a representative payee and the resulting impact on their substance use, budgeting, and housing. The clients' clinical case managers completed a similar questionnaire. Analyses examined associations between providers' and clients' responses and clients' gender, race, diagnosis, previous experience with a representative payee, and duration of the current representative payeeship. RESULTS: Clients and case managers recognized benefits of the representative payeeship in the areas of housing, substance use, and budgeting. Although little evidence was found that the payeeship pervasively interfered with the therapeutic relationship, 44 percent of case managers reported incidents in which clients verbally abused them over management of their funds. Clients' satisfaction with the representative payeeship was initially low but grew over time. Longer duration of the current payeeship and clients' previous experience with representative payeeship were associated with greater satisfaction and fewer problems. Case managers overestimated clients' initial satisfaction and underestimated their current satisfaction. CONCLUSIONS: Findings suggest that both mental health professionals and clients value the representative payee process as helpful in improving outcomes, although the benefits of the arrangement may be more evident with time and experience.

In 1993, a total of 26 percent of recipients of Social Security Disability Insurance and 29 percent of recipients of Supplemental Security Income qualified for benefits due to a mental illness (1). About 47 percent of these two groups use a representative payee. In such programs, a person or agency is appointed to receive and disburse benefit income because a client has a substance use disorder or has been deemed incapable of managing his or her money due to medical or psychiatric impairments. The payee budgets money for rent, food, clothing, and other necessities.

Given the frequency with which persons with severe mental illness have a representative payee, remarkably little is known about the impact of these programs. Previous studies have suggested that having a representative payee leads to declines in homelessness, victimization, and arrest (2), enhanced participation in treatment (2,3), and reduced hospitalization (4), but not reduced substance abuse (5).

No previous studies have systematically investigated the perceptions of and understandings between the client and therapist payee with regard to the representative payee relationship. The potential administrative and ethical dilemmas for the therapist, detriments to the therapeutic alliance, and transference and countertransference inherent in the role of representative payee are considerable (6). One hypothesis is that the relationship causes conflict between the client and the therapist due to the nature of the arrangement, which may be coercive, and that these conflicts lead to poor outcomes and ability to carry out representative payee functions. An understanding of providers' and clients' perceptions of the representative payee relationship might help improve outcomes related to use of representative payees.

The objective of this study was to describe and compare clients' and case managers' perceptions of the impact of a representative payee program delivered as part of an assertive community treatment program in a community mental health setting. We examined satisfaction with the program, impact on outcomes, and effects on the therapeutic relationship as a function of the representative payee's time and previous experience as a representative payee. We hypothesized that time and experience would improve the functioning of the representative payee relationship.

Methods

The study site was an inner-city assertive community treatment program serving homeless clients with severe mental illness. The team's effectiveness in reducing hospitalization and homelessness was documented in a randomized controlled trial (7). The operations of the team and its representative payee program have been described extensively (8,9). Subjects were also drawn from a companion program, a mobile treatment unit, that uses a similar model; it serves patients who are not homeless but who have frequent hospitalizations and use of crisis services.

The study was conducted between March and May 1996 and included all clients in the assertive community treatment program and the mobile treatment unit for whom these entities had been the representative payee for at least three months. The mean±SD age of the 54 clients who participated in the study was 41.1± 10.58 years. Twenty-eight clients (52 percent) were men. Nineteen clients (35 percent) were Caucasian, and 35 (65 percent) were African American. At the time of the interview, 35 clients (65 percent) resided independently in their own accommodations—that is, not with family or other caregivers.

The medical charts provided psychiatric diagnoses. Treating physicians diagnosed 33 clients (61 percent) as having schizophrenia, 18 (33 percent) as having an affective disorder, and three (6 percent) as having a substance-induced mental disorder. Thirty-five clients (65 percent) had a substance use diagnosis.

Primary clinical case managers who were paired with clients in the representative payee program were interviewed; a total of 54 case manager-client pairs were included. Nine of the 11 case managers were women. Four were nurses, four were social workers, and three were trained in other disciplines. Five had a master's degree, five had a bachelor's degree, and one had an associate degree. Although the program was the officially designated payee, the clinical case managers fulfilled most of the day-to-day duties of the payee.

Staff members who were not involved in the direct care of the client interviewed the client as part of a quality assurance program. Clients were asked two questions about their overall satisfaction with their representative payee experience: How did you feel when the [assertive community treatment team or mobile treatment team] became your payee? and, Overall, how do you feel about the program being your payee now? Responses were coded on a 5-point scale from 1, very unhappy, to 5, very happy. Clients were asked if they agreed or disagreed with the following statements: The program acting as my representative payee has helped me maintain my housing; the program helped me control my substance use; and the program helped me make my money last the entire month.

To assess the impact of the representative payee program on the therapist-client alliance, clients were asked if they agreed or disagreed with these statements: I come to the [assertive community treatment program or mobile treatment unit] only to receive money, and, I can't talk to my therapist about my feelings or symptoms because he or she controls my funds.

Clinical case managers completed a questionnaire that was similar to the client interview. They were asked if they thought that the client had wanted the program to act as a payee, and if the client benefited from the representative payeeship in the areas of housing, substance abuse, and money management. Additional questions asked about the impact of the representative payee on the therapeutic relationship and incidents in which clients verbally abused the case manager over management of their funds. Case managers were also asked about reasons for establishing a representative payee relationship with the client.

Data analysis

Chi square analyses for categorical data and nonparametric between-group tests for ordinal data were conducted to assess the associations of clients' gender, race, diagnosis, previous experience with a representative payee, and length of the current representative payee relationship with client satisfaction and perceptions. Responses of the case managers and concordance and discordance between responses of the case manager-client pairs are summarized as frequencies and percentages.

Results

Not unlike participants in representative payee programs previously studied (5), clients had a representative payee for several reasons. Thirty-eight (70 percent) had one for psychiatric problems, 28 (52 percent) for substance use, and 36 (67 percent) for homelessness. More than half (33 clients, or 61 percent) had a representative payee because of multiple problems. Twenty-four clients (44 percent) had previously had a representative payee, and for 32 clients (59 percent) the current program had acted as representative payee for more than a year.

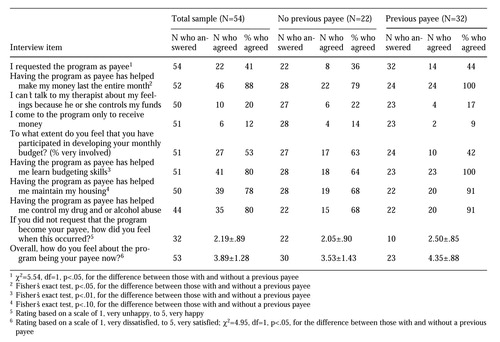

Table 1 presents the clients' views about the helpfulness of having the assertive community treatment team or the mobile treatment unit as a representative payee. For the majority of clients, initial satisfaction with having the program act as a representative payee was low; however, their current satisfaction was high. Most clients reported that they did not ask that the program become their representative payee. Of the 32 clients who did not ask the treatment program to act as payee, two (6 percent) reported that they were initially happy or very happy with the program as payee. At the time of interview, 22 of the 32 clients who did not ask that the program become the payee (69 percent) were happy with the program as payee.

Overall, clients agreed strongly with items indicating that they felt the representative payee program was helpful; their responses also indicated that they did not perceive the payeeship as interfering with the therapeutic relationship. Gender, race, and diagnosis were not related to clients' perceptions.

Clients for whom the program had acted as payee for more than a year reported greater current satisfaction with the representative payeeship. The mean±SD satisfaction score for clients in the payee program for more than a year was 4.16±1.13, compared with 3.50±1.40 for clients in the program for less than a year (χ2=4.15, df=1, p<.05). Clients with a payee relationship of longer than a year were more likely to agree that this mechanism helped them control their substance abuse; of the 25 clients with a relationship longer than a year, 23 (92 percent) agreed with that statement, compared with 12 of the 19 clients (63 percent) whose payee relationship had lasted less than a year (χ2=5.52, df=1, p<.05). The numbers do not add to 54 due to missing data for three clients.

As Table 1 shows, clients with previous experience in a representative payee program were more satisfied with the current payee program at the time of the interview than clients with no previous experience with a representative payee. In addition, clients who previously had a representative payee were more likely to agree that the current representative payee helped them make their money last all month, learn budgeting skills, and maintain their housing.

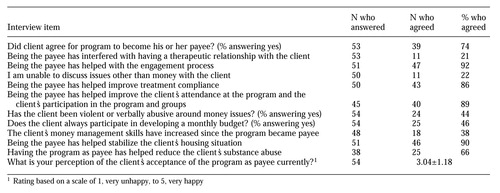

Table 2 shows the clinical case managers' views about their representative payee role. Clients' gender, race, and diagnosis were not related to the perceptions of the case managers. Case managers of clients who had been in the current representative payee program for less than a year were more likely to agree with the statement, You are unable to discuss issues other than money with the client. For the 20 clients who had participated in the representative payee program for less than a year, eight case managers (40 percent) agreed with that statement, compared with three case managers of the 31 clients (10 percent) who had participated for more than a year (Fisher's exact test, p<.05).

Case managers perceived clients who had payee relationships longer than one year as more accepting of the payee relationship; on the 5-point scale, case managers' mean±SD rating of the acceptance of clients in this group was 3.38± 1.10, compared with a rating of 2.54±1.14 for clients who had had a payee for less than a year (χ2=6.53, df=1, p<.05). A significantly greater proportion of clients with previous representative payee experience were perceived by case managers to have agreed to the current payeeship; of the 24 clients who had previous experience with a representative payee, 23 (95 percent) were perceived by case managers as having agreed, compared with 16 of 29 clients (53 percent) with no previous representative payee experience (Fisher's exact test, p<.01). For one client, previous experience with a representative payee could not be definitively determined.

Case managers reported that 24 of the 54 clients in the sample (44 percent) engaged in verbal abuse of the case manager that was attributable to the representative payee relationship. Such clients were more likely to have a substance use disorder; of the 24 clients who engaged in incidents of verbal abuse, 19 (79 percent) had a substance use diagnosis, compared with 16 of the 30 clients (53 percent) who did not engage in verbal abuse (χ2=3.90, df=1, p<.05). Verbal abuse was not associated with clients' or case managers' ratings of satisfaction with the representative payee program.

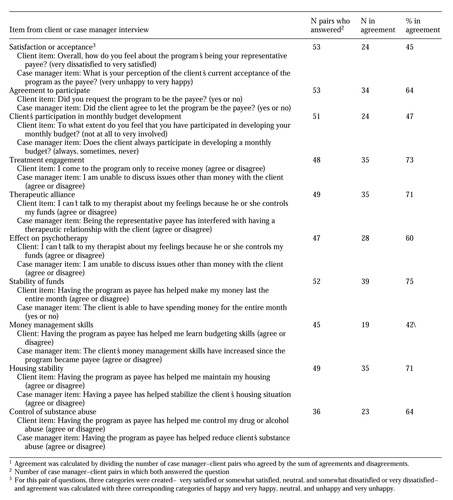

Table 3 shows the percentage of agreement or concordance between case manager-client pairs on similar items in the interviews. Overall, concordance ranged from 47 percent to 75 percent. Concordance about the client's desire to have the treatment program act as payee was 64 percent. Case managers overestimated clients' agreement to have the program act as payee (Table 1 and Table 2). Concordance about the client's current satisfaction with payeeship was only 47 percent. In this case, case managers underestimated clients' current satisfaction (Table 1 and Table 2). Lower levels of concordance (less than 50 percent) were found for clients' participation in budgeting and the impact of having a representative payee on budgeting skills.

Discussion and conclusions

Results of the exploratory study indicate that clients and clinical case managers viewed the representative payee program favorably and appreciated its impact on areas of housing stability, substance use, and money management. Little evidence was found to support the assertion that representative payeeship pervasively interferes with the therapeutic relationship. Although a subgroup of clients with a high rate of substance abuse engaged in verbal abuse of their case manager that was attributable to the payee relationship, the high rates of satisfaction and perceived benefit suggest that issues raised by having a representative payee were managed by most of the case manager-patient dyads.

The data suggest that clients may initially reject a representative payee but over time become more satisfied with the arrangement. The association of higher satisfaction and better outcomes with clients' previous experience with a representative payee and longer duration of the current payeeship suggests that both clients and case managers may learn how to work more effectively with the representative payee process. A growing therapeutic alliance fostered by attention to multiple domains may strengthen the ability of case managers and clients to work on representative payee issues. Variability in clients' satisfaction with their representative payee may also be related to how clearly the policies involved in monetary disbursement are elucidated and how well they are understood by both parties (10).

The clinical case managers' initial overestimation of clients' willingness to have the team as a payee and their underestimation of clients' current satisfaction with having a payee is intriguing. Perhaps case managers initially do not appreciate clients' fears about losing control over their funds and the threat to autonomy that payeeship represents. As case managers' understanding of the client grows and they experience some of the stresses of being a representative payee, they may both overidentify with the client's objections to the arrangement and project onto the client their own dissatisfaction and discomfort with being a representative payee.

Although the study found relatively high levels of agreement between case managers and clients about the benefits of representative payeeship, it is noteworthy that the two items with the least concordance involve money—the extent of the client's involvement in budgeting and the client's acquiring budgeting skills. This finding suggests that the essence of the representative payee arrangement, client-case manager collaboration in money management, is one area where more effective communication is needed.

Limitations of this study include its reliance on retrospective reports and lack of objective evaluation of outcomes of the representative payee program. However, to our knowledge it is the first study to obtain clients' and providers' dyadic perceptions of representative payeeship. Both of the groups shared a favorable view of representative payeeship, although some threats to the therapeutic process were noted due to incidents of verbal abuse. Additional areas of concern include subtle shifts in the concordance between case managers and clients with respect to client satisfaction over time and the lack of agreement between case managers and clients about the client's participation in money management and budgeting.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grant K20-MH-01250-01 to Dr. Dixon from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the Center for Mental Health Services Research of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland, 701 West Pratt Street, Baltimore, Maryland (e-mail, [email protected]). Parts of this work were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held May 30 to June 4, 1998, in Toronto.

|

Table 1. Responses of 54 clients interviewed about their current experience of having a representative payee, by whether they previously had a representative payee

|

Table 2. Responses of 54 case managers interviewed about their role as a representative payee

|

Table 3. Concordance between the responses of clinical case managers and clients to similar items in separate interviews about their experience in a representative payee program1

1. Kochhar S, Scott CG: Disability patterns among SSI recipients. Social Security Bulletin 58:3-14, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

2. Stoner MR: Money management services for the homeless mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:751-763, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Ries R, Comtois KA: Managing disability benefits as part of treatment for persons with severe mental illness and comorbid drug/alcohol disorders: a comparative study of payee and non-payee participants. American Journal on Addictions 6:330-338, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

4. Rosenheck R, Lam J, Randolph F: Impact of representative payees on substance use by homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:800-806, 1997Link, Google Scholar

5. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Conrad KJ, et al: An agency-based representative payee program and improved community tenure of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:1218-1222, 1988Link, Google Scholar

6. Brotman AW, Muller JJ: The therapist as representative payee. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:167-171, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Lehman A, Dixon L, Kernan E, et al: A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1038-1043, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Dixon L, Krauss N, Kernan E, et al: Modifying the PACT model for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:684-688, 1995Link, Google Scholar

9. Dixon L, Kernan E, Krauss N, et al: Assertive community treatment for homeless adults with severe mental illness in Baltimore, in Mentally Ill Homeless: Special Programs for Special Needs. Edited by Breakey WR, Thompson JW. New York, Harwood, 1997Google Scholar

10. Ries RK, Dyck DG: Representative payee practices of community mental health centers in Washington State. Psychiatric Services 48:811-814, 1997Link, Google Scholar