Characteristics of Representative Payeeship Involving Families of Beneficiaries With Psychiatric Disabilities

An estimated one million individuals with psychiatric disabilities do not receive Social Security Administration (SSA) benefits directly. Because they are deemed unable to manage money, their support is handled through a representative payee who ensures their basic needs are met for food, shelter, clothing, and medical expenses ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). Although SSA data indicate that over 70% of payees of adults with psychiatric disabilities are family members ( 1 , 2 ), family payeeship has received relatively little attention in the empirical literature. The purpose of this study was to provide data describing representative payeeship involving family members of consumers with psychiatric disabilities.

A review of the research shows that, for persons with psychiatric disabilities, payees can be instrumental in promoting residential stability, basic health care, and engagement in psychiatric treatment ( 4 ). Representative payeeship has been shown to be associated with reduced hospitalization, victimization, and homelessness ( 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ). Treatment adherence is better among consumers with payees than those without ( 9 , 10 ). Payees who used monetary reinforcement increased abstinence among consumers with dual psychiatric and substance use disorders ( 11 ), although this effect has not always been found ( 6 ). In a recent study, payeeship for persons with psychiatric disabilities was associated with reduced substance abuse, improved quality of life, and better money management ( 12 ).

However, studies suggest that payeeship may be used coercively and may thwart consumer self-determination. Although discretionary funds may sometimes be used by payees to support treatment adherence ( 13 ), payees can also use contingent money management in ways that increase conflict and have no shared therapeutic purpose ( 14 , 15 , 16 ). This finding was verified in a study of financial coercion experienced by people with psychiatric disabilities ( 17 ). In another study, over half of consumers surveyed agreed with the following statements: "My payee has too much control over me," "I was pushed to appoint a payee," and "I do not agree with the spending decisions that have been forced on me" ( 18 ).

In addition, representative payeeship may exacerbate dependency fostered by disablement and reduce incentives to work. Studies show consumers experience less incentive to work when they receive disability benefits ( 19 ). The inability to control one's money could further exacerbate a dependency role fostered by the disability process. Unless consumers are provided a means to set a goal of terminating the representative payeeship and managing their own funds—which they typically are not—they are vulnerable to remaining dependent on their payees indefinitely ( 20 ). This situation may, in part, be due to misunderstandings of the payee arrangement; SSA audits indicate limited understanding among both consumers and payees about representative payeeship ( 21 ).

Finally, representative payeeship may increase interpersonal conflict and precipitate violence in families. Consistent with research showing that finances are among the most common reasons for arguments within caregiver relationships ( 22 , 23 ), consumers with psychiatric disabilities have been shown to act aggressively toward a family member on whom they are financially dependent ( 24 ). One study found family representative payeeship doubled the odds of serious family violence, even after relevant covariates were controlled for; if the consumer had frequent contact with the payee, the risk of family violence quadrupled ( 25 ). Another study found that when discussing issues concerning management of funds, 44% of case manager payees reported incidents in which consumers became verbally abusive ( 26 ).

Relatively few of these studies focused on family payeeships. One study showed that consumers with family payees were younger than consumers with nonfamily payees ( 27 ), but overall very little is known about family payeeships, and many questions remain: Do consumers and their family payees report experiencing the aforementioned benefits and problems of payeeship? Are there consistent limitations in knowledge of payeeship among consumers and payees, perhaps some that might encourage dependency? If payeeship is associated with conflict, what are the contributing factors? Do payees have better basic money management skills than consumers whose money they manage? This study aimed to address these questions in order to gain a better understanding of family representative payeeship when a family member has psychiatric disabilities.

Methods

Sample

One hundred participants (50 dyads of consumers with psychiatric disabilities and their family representative payees) were interviewed between October 2005 and January 2007 to collect data on perceived benefits and problems of the payeeship, knowledge of payee guidelines, the consumer-payee relationship, arithmetic and money management skills, and payeeship characteristics. Consumer participants were enrolled in a previous research study where they were randomly selected from comprehensive, deidentified lists provided by two mental health centers in North Carolina of all clients who met the following inclusion criteria: age 18–65; chart diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, other psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder with psychotic features; and current receipt of community-based treatment. For this study the additional criterion for inclusion was having a representative payee who was a family member.

Procedure

All of the consumers meeting the above criteria were initially contacted by a research interviewer to confirm eligibility and obtain informed consent. Using the study's informed consent document, the interviewer explained the nature and the purpose of the research, standard protections for human participants, and risks and benefits of the study. If the consumer consented and reported currently having a family representative payee, we then obtained informed consent from that family member. If either the family member or consumer declined informed consent, we considered this a refusal and enrolled neither person in the study. Basic demographic and clinical descriptors and a checklist of reasons for refusal were collected from persons who declined to enroll.

With use of the aforementioned approach, recruitment was successful 74% of the time. There were no significant differences in diagnosis, type of payeeship, gender, or ethnicity between consumer-payee dyads that consented and those that refused to enroll. Despite our initial concern that consumers or family payees might be reluctant to participate in a study about personal finances, very few declined for this reason. Instead, the most common reason that anyone declined was that family members reported that they were not interested in participating in research studies. After providing informed consent, the consumer and family payee were interviewed separately by a trained research technician for approximately one hour each. Consumers and family payees were paid $25 each for their participation.

Instruments

Because few studies have examined family representative payeeship when a family member has psychiatric disabilities, we constructed questions aimed at identifying consumers' and payees' perceptions of the arrangement. Specifically, we created questions on perceived benefits, perceived downsides, knowledge of payeeship, and payee characteristics. When measures were available, such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT 3), we used them. When measures were lengthy, such as money management tasks derived from validated instruments, we created a condensed version. Our measures were tested for feasibility with three consumers and three family payees whose data were not included in analyses. All pilot participants found that responding to questions was easy and that the interview was not burdensome, taking a maximum of 60 minutes to complete.

Demographic and clinical data. Data collected for both consumer and payee included age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, current employment, and education. Data for consumers included psychiatric diagnosis and data from the BPRS ( 28 ), which were analyzed as a four-factor model measuring thought disturbance, anergia, affect, and disorganization ( 29 ). Payees rated their own mental well-being.

Payeeship characteristics. Consumers and payees answered questions about how the payee and consumer were related, whether consumers lived with their payees in the past six months, and how long the payee arrangement had been in place (measured in months). Consumers were also asked to rate how well they trusted the payee (from 1, strongly agree, to 4, strongly disagree) and how satisfied they were with working with the payee in the past month in terms of taking care of disability income (from 1, extremely satisfied, to 6, fairly dissatisfied).

Perceived benefits of payeeship. Consumers and payees were asked whether payeeship improved treatment adherence, reduced hospitalizations, reduced homelessness, reduced alcohol use, reduced illicit drug use, and ensured medical bills were paid. Each item was coded dichotomously; participants who responded "always" or "often" were coded as endorsing the benefit of payeeship, whereas those who replied "sometimes" or "never" were coded as not endorsing the benefit of payeeship.

Perceived problems of payeeship. Consumers and payees were asked whether payeeship was implemented coercively, led to family conflict, made the consumer feel embarrassed, and made the consumer feel not in control of his or her life. In addition, respondents indicated whether they thought they needed more information about payeeship, better budgeting within the payeeship, and greater input from consumers on daily money decisions. Each item was coded dichotomously; responses of "always" or "often" were coded as endorsing a problem in the payeeship, whereas responses of "sometimes" or "never" were coded as not endorsing a problem in the payeeship.

Knowledge of payeeship. Consumers and payees were asked five true-false questions based on information in Social Security Administration Guidebook for Representative Payees provided by the SSA to disability recipients and their payees ( 3 ). A composite score was created on the basis of the number of correct answers.

Arithmetic and money management skills. The arithmetic section of the WRAT 3 was administered to both consumer and payee ( 30 ), which created a grade-level equivalent for math abilities. A brief money management skills task was adapted from a more comprehensive money management assessment ( 31 ). The current task involved a credit card bill that listed a previous balance and cost of three purchases that needed to be summed with the aid of a calculator. Participants also were asked to write a check to the credit card company and to stamp and address an envelope to the credit card company. A total score of each of the items correct is denoted below as "money skills." The items on this exercise showed good internal consistency for consumers ( α =.90) and payees ( α =.87), suggesting that the exercise reliably tapped into the construct of money management skills.

Analysis

Univariate statistics were used to describe characteristics of consumers and their family payees. When data were skewed, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney nonparametric procedures were used to test for group differences. Variables indicating skewed distributions were transformed into dichotomous variables that were split at the median. This transformation was necessary to determine both consumer trust in the payee and consumer satisfaction with payeeship. Chi square analyses were used to compare consumer and payee responses to perceived benefits and problems, knowledge of payeeship, and items on the money management task. Student's t tests were used to compare consumers' and payees' overall scores on the WRAT 3 and money management exercise. Four payees and three consumers did not want to complete the WRAT 3 or the money management exercise; therefore, their data were considered missing for descriptive analyses of these two variables and were replaced with the mean scores on these two variables for multivariate analyses.

Finally, three multivariate analyses were run to ascertain predictors of conflict and coercion in the payeeship. Dependent variables included consumer perception of not controlling one's life, consumer perception of conflict and arguments, and payee perception of conflict and arguments. Independent variables included demographic and clinical data, payee characteristics, perceived benefits and problems, composite knowledge of payeeship, and composite money management skills. Stepwise logistic regression analyses were used in which independent variables were excluded from subsequent analyses if they did not meet a probability level of .10. Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests showed adequate goodness of fit for the three logistic regression models we used.

Results

Half of the consumer-payee dyads involved a parent as the representative payee, and 28% involved a sibling as the payee. The remaining dyads involved two payees who were consumers' grandparents (4%), five spouses (10%), and four other relatives (8%). About half (48%) of the consumers lived with their payee in the past six months. Thirty-seven payees (74%) were women, and the mean±SD age of payees was 58.00±14.48 (range 27–83). A total of 27 consumers (54%) were men, and the average age of consumers was 44.80±10.07 (range 26–64). Twenty-nine payees and consumers (58%) were African American, and 21 (42%) were Caucasian. With respect to consumers' education level, 15 (30%) dropped out of high school, 22 (44%) completed high school only, and 13 (26%) took college courses; only two consumers reported having graduated from college. With respect to payees' education level, 12 (24%) dropped out of high school, 19 (38%) completed high school only, and 19 (38%) took college courses; eight payees (16%) reported having graduated from college. Twenty-five (50%) payees reported working for pay in the past month, whereas only six (12%) consumers reported any employment. Twenty-one payees (42%) were currently married, and only five (10%) consumers were married.

Clinically, 39 (78%) consumers had chart diagnoses of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder, eight (16%) were diagnosed as having bipolar disorder, and three (6%) had major depressive disorder with psychotic features. Payees generally rated their own mental health as excellent (14, or 28%) or good (30, or 60%), with six (12%) indicating poor or fair mental health. With respect to payee characteristics, the average length of payeeship was 8.75±8.29 years, ranging from one month to 25 years. In terms of payee relationships, most consumers strongly agreed (30, or 60%) that they trusted their payee and were extremely satisfied (28, or 56%) with how they and the payee work together.

Consumer and payee perceptions of benefits and problems associated with representative payeeship are presented in Table 1 . About one-third of consumers and payees believed payeeship helped reduce substance abuse and improve consumer treatment adherence. About half of consumers and payees also reported that payeeship lowered the risk of homelessness and ensured that medical bills were covered. With respect to problems, more than one-third of payees and consumers reported that money was withheld from the consumer. Significantly more consumers than payees endorsed that payeeship leads the consumer to feel not in control of his or her life (26% versus 8%; χ2 =5.74, df=1, p<.05). Most consumers and payees cited areas for improvement in the payeeship, including a need for more payeeship information, education about budgeting, and more consumer input into daily money decisions. Half of the payees and more than one-third of consumers indicated that the payee relationship frequently leads to arguments and conflict.

|

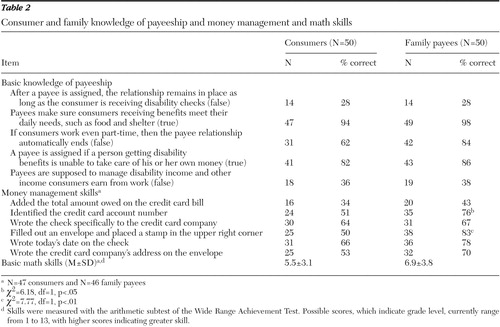

Table 2 provides descriptive data on knowledge of payeeship, money management skills, and math skills. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of knowledge of payeeship. Only 28% of payees and consumers knew that payeeship did not last indefinitely, and a little more than one-third knew that payees managed only disability funds and not other income that consumers earned from work. A total of 38% of consumers incorrectly thought that if they worked the payeeship would end. Regarding the money management skills exercise, the total number of correct answers did not differ between consumer and payee. Less than half of both groups were able to correctly add the total on a credit card bill. Payees were more likely to correctly fill out the envelope (82% versus 50%; χ2 =6.18, df=1, p<.05) and identify the credit card number; χ2 =7.77, df=1, p<.01) than were consumers. Math abilities between consumers (mean±SD=5.5±3.09 grade level, range=1–13 or higher) and payees (6.9±3.75 grade level, range 1–13 or higher) did not differ to a level of statistical significance.

|

We also examined factors associated with payee problems ( Table 3 ). Consumers' perceptions that payeeship led to their feeling less control over their lives was positively predicted by the length of the payeeship (odds ratio [OR]=1.01) and negatively predicted by a consumer's reported trust in the payee (OR=.08). Consumers' perceptions that the payeeship led to frequent conflict was negatively predicted by their satisfaction with the payeeship (OR=.35) and positively predicted by their money management skills (OR=1.74) and their level of disorganization on the BPRS (OR=1.48). Finally, payees' perceptions that the payeeship led to frequent conflict was negatively predicted by their having graduated from high school (OR=.09) and by consumers' reported trust in the payee (OR=.17). Of note, diagnosis and arithmetic skills did not affect these three outcomes.

|

Discussion

Given the prevalence of representative payeeship, legal scholars have called it "the nation's largest guardianship system" ( 32 ). In this study, we examined basic perceptions and knowledge of consumers with psychiatric disabilities and their family payees. We found that most consumers and payees believed payeeship led to greater living stability; however, nearly half reported it was also associated with arguments and conflict. Many consumers also felt embarrassed by the arrangement and thought payeeship reduced autonomy, although payees were less aware of this. Perhaps the most salient finding was that we failed to find differences between payees and consumers with respect to knowledge of payeeship and basic money skills. Instead, we found that both consumers and payees showed gaps in knowledge of payeeship, with only 28% demonstrating awareness that payeeship did not last indefinitely. Also, both groups showed deficiencies in basic arithmetic and money management skills.

Although payeeship was seen to have benefits, the data revealed potential problems and gaps in knowledge and skills among consumers and payees. Of note, the results confirmed that risk of family conflict was associated with payeeship, consistent with other research ( 24 , 25 ). Our multivariate analyses suggest that when payees have less education and consumers have better money management skills, then the payeeship is more likely to lead to conflict. To assign a payee, the SSA runs a criminal background check and credit report on potential payees but does not formally evaluate the ability of the payee to manage finances or consider at all the payees' level of education. As a result, consumers may find their disability checks controlled by family members who have limited money management skills of their own. Indeed, the basic descriptive findings on level of abilities among payees was somewhat surprising and signals a need to screen family payees so that the SSA does not inadvertently create circumstances that exacerbate family stress, strain, conflict, and even violence.

Treatment providers who encounter family payeeships should investigate whether there is a disparity between payee and consumer in terms of money management, specifically whether the payee is able to manage disability checks. If this is not the case, these data indicate a significant risk of conflict. However, even though some people with psychiatric disabilities may be better at financial management than their payee, providers should recognize that consumers may not have better judgment regarding how to handle their disability funds. Thus assessing both basic skills and financial judgment is important.

Another finding regarded the relative lack of basic knowledge among consumers and their payees. The fact that most payees and consumers thought the payeeship lasted indefinitely is of concern because this belief could contribute to dependency on an arrangement that is no longer necessary. Policy changes at the SSA regarding educating payees and consumers could help address this problem ( 21 ), perhaps by meeting with candidate payees or tailoring brochures to the level of understanding of the payee. Further, follow-up evaluations over regular time intervals of a consumer's ability to manage his or her own money could be useful in terms of detecting when payeeship is no longer necessary. Although payees' skills and knowledge did not predict outcomes in our multivariate models, if payees' skills or knowledge were to improve, then one would expect other outcomes to improve that were not examined in this study, including termination of unnecessary payeeships or increased encouragement of the consumer to work.

With respect to psychiatric services, clinical efforts to improve accurate knowledge of payeeship seem warranted. For example, helping payees and consumers recognize that a consumer can manage his or her own earned income from work seems very likely to improve a consumer's incentive to work in the first place. In light of the common use of payees for consumers receiving assertive community treatment ( 33 ), clinicians could help educate payees as well as consumers that the arrangements are not indefinite and are based on mutual agreement about the need for third-party money management. Indeed, a recent review of family money management provides specific clinical case illustrations of how service providers can help to improve trust between payees and consumers ( 34 ).

Overall, one significant SSA policy change could be to ensure that the payees pass some type of test to demonstrate basic ability to manage personal finances. But this raises the possibility that a consumer will have no family member with the knowledge base to properly manage finances. The SSA could find someone who is not a family member with the required knowledge to be a payee, but that might expose a consumer to a payee he or she is not associated with—and who might be more likely to exploit the consumer's funds because the payee is not a family member. Therefore, because there may be cases in which a consumer would be unable to find a trusted person to act as payee who also has the required abilities and knowledge, the SSA may need to seriously consider investing in more institutionally based payees to serve this group of consumers ( 35 ). Regardless of how this would be done, our findings indicate that a useful first step would be to develop a process by which payees with inadequate competency could be identified.

From a clinical perspective, the data provide several clues for improving family payeeship arrangements. Both payees and consumers reported a need for consumer involvement in money decisions; clinical efforts to increase collaboration between payees and consumers could help address problems of payeeship ( 36 ). Further, both groups indicated needing help with budgeting and reducing debt. For these reasons, the findings suggest that by facilitating collaboration on money matters, increasing SSA knowledge, fostering collaborative and effective money management, and developing plans for financial decision making, treatment providers can promote independent functioning and family support for many individuals with psychiatric disabilities.

It is important to recognize that this study was cross-sectional; therefore, causal relationships between factors and perceived problems of payeeship cannot be determined. The main limitation of the study is the potentially limited generalizability of findings to other family representative payee arrangements. The distribution of consumers' diagnoses in this study generally agreed with other published studies on the characteristics of consumers who have payees ( 27 , 37 ). Further, the type of representative payee arrangement was parallel to that reported by the SSA for people with psychiatric disabilities ( 1 , 2 ). Finally, although the sample was not representative of the U.S. population in terms of ethnicity and it is unknown whether age was representative, data from a recently published report by the National Research Council Committee on Social Security Representative Payees show that the payees in this study closely resemble payees nationally in terms of education levels: "The educational level of representative payees is somewhat lower than the national average with 76.6 percent having graduated from high school and only 13.3 percent having a college degree. For comparison, in 2003, nationally, 84 percent of people 25 years and older had at least graduated from high school and 27 percent had a bachelor's degree or higher" ( 38 ). Future research is needed to determine whether our findings can be replicated in different regions or in payee arrangements involving different types of disabilities.

It is important to note that these consumers were randomly selected from all clients who received services at the local mental health centers and had the aforementioned psychiatric diagnoses. Further, it was somewhat surprising to uncover evidence that payees had poor knowledge of payeeship and lacked basic money management skills. Although it could be argued that the money management exercise may have been too challenging (for example, maybe consumers would not have credit cards), one would then expect that payees would perform better than consumers. However, as described above, we did not find this. Relatively poor basic financial skills are also consistent with results from the WRAT 3 arithmetic subtest. Future efforts are therefore needed to interview more consumers and family payees to determine whether the patterns revealed in these data are replicated for larger samples or whether certain factors predict better or worse outcomes (for example, do consumers who work have a better understanding of payeeship?). Such research would also be important to more fully describe any commonalities or differences between payee relationships involving different family member roles.

One final limitation of this study was an inability to accurately detect whether intentional payee abuse occurred given that our measures relied on self-report. Data from the SSA indicate that such abuse occurs in less than .01% of payee arrangements ( 39 ); instead, the findings illuminate an arguably more common problem of unintentional misuse of payeeship, which may occur if consumers or payees lack an accurate understanding of how the arrangement works.

Conclusions

For people with psychiatric disabilities, family payeeship poses potential problems but also holds great promise. On the one hand, one of every three adults who receive SSA income for psychiatric disabilities has a payee, and family payees represent a valuable, yet largely untapped, resource to help consumers with psychiatric disabilities maintain living stability, build independent living skills, use money for socialization rather than substances, and strive toward realistic life goals. On the other hand, the data indicate that a representative payee appears to be associated with perceptions of potentially negative consequences, including conflict, coercion, and dependency. Consumers and payees may lack basic knowledge of payeeship and money management skills, and if misunderstood or misused, payee arrangements could undermine rehabilitation efforts. Therefore, this study confirms that efforts to address possible downsides of this prevalent legal mechanism could improve the lives of a substantial number of people with psychiatric disabilities as well as their families.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. 2004 Annual Statistical Report. Washington, DC, Social Security Administration, 2005Google Scholar

2. 2004 Annual Statistical Report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program. Washington, DC, Social Security Administration, 2006Google Scholar

3. A Guide for Representative Payees. Washington, DC, Social Security Administration, 2004Google Scholar

4. Luchins DJ, Roberts DL, Hanrahan P: Representative payeeship and mental illness: a review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 30:341–353, 2003Google Scholar

5. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Conrad KJ, et al: An agency-based representative payee program and improved community tenure of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:1218–1222, 1998Google Scholar

6. Rosenheck R, Lam J, Randolph F: Impact of representative payees on substance use by homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:800–806, 1997Google Scholar

7. Stoner MR: Money management services for the homeless mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:751–753, 1989Google Scholar

8. Hanrahan P, Luchins DJ, Savage C, et al: Representative payee programs for persons with mental illness in Illinois. Psychiatric Services 53:190–194, 2002Google Scholar

9. Ries RK, Comtois KA: Illness severity and treatment services for dually diagnosed severely mentally ill outpatients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:239–246, 1997Google Scholar

10. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS: Effects of legal mechanisms on perceived coercion and treatment adherence among persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:629–637, 2003Google Scholar

11. Shaner A, Roberts LJ, Eckman TA, et al: Monetary reinforcement of abstinence from cocaine among mentally ill patients with cocaine dependence. Psychiatric Services 48:807–810, 1997Google Scholar

12. Conrad KJ, Lutz G, Matters MD, et al: Randomized trial of psychiatric care with representative payeeship for persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 57:197–204, 2006Google Scholar

13. Monahan J, Bonnie RJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Mandated community treatment: beyond outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 52:1198–1205, 2001Google Scholar

14. Marson DC, Savage R, Phillips J: Financial capacity in persons with schizophrenia and serious mental illness: clinical and research aspects. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:81–91, 2006Google Scholar

15. Cogswell SH: Entitlements, payees, and coercion, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment: A New Frontier in Mental Health Law. Edited by Dennis DL, Monahan J. New York, Springer, 1996Google Scholar

16. Rosen M, Desai R, Bailey M, et al: Consumer experience with payeeship provided by a community mental health center. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 25:190–195, 2001Google Scholar

17. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS: Psychiatric disability, the use of financial leverage, and perceived coercion in mental health services. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 2:119–127, 2003Google Scholar

18. Rosen M, Bailey M, Dombrowski E, et al: A comparison of satisfaction with clinician, family members/friends, and attorneys as payees. Community Mental Health Journal 41:291–306, 2005Google Scholar

19. Estroff SE, Patrick DL, Zimmer CR, et al: Pathways to disability income among persons with severe, persistent psychiatric disorders. Milbank Quarterly 75:495–532, 1997Google Scholar

20. Rosenheck R: Disability payments and chemical dependence: conflicting values and uncertain effects. Psychiatric Services 48:789–791, 1997Google Scholar

21. Monitoring Representative Payee Performance: Roll-Up Report, vol 2004. Washington, DC, Social Security Administration, 1997Google Scholar

22. Saunders JC: Families living with severe mental illness: a literature review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 24:175–198, 2003Google Scholar

23. Baronet A-M: Factors associated with caregiver burden in mental illness: a critical review of the research literature. Clinical Psychology Review 19:819–841, 1999Google Scholar

24. Estroff SE, Swanson JW, Lachicotte W, et al: Risk reconsidered: targets of violence in the social networks of people with serious psychiatric disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33(suppl):S95–S101, 1998Google Scholar

25. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al: Family representative payeeship and violence risk in severe mental illness. Law and Human Behavior 29:563–574, 2005Google Scholar

26. Dixon L, Turner J, Krauss N, et al: Case managers' and clients' perspectives on a representative payee program. Psychiatric Services 50:781–786, 1999Google Scholar

27. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al: Characteristics of third-party money management for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 54:1136–1141, 2003Google Scholar

28. Woerner MG, Mannuzza S, Kane JM: Anchoring the BPRS: an aid to improved reliability. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 24:112–117, 1988Google Scholar

29. Mueser KT, Curran PJ, McHugo GJ: Factor structure of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale in schizophrenia. Psychological Assessment 9:196–204, 1997Google Scholar

30. Snelbaker AJ, Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ, et al: Wide Range Achievement Test 3 (WRAT 3), in Understanding Psychological Assessment. Edited by Dorfman WI, Hersen M. Dordrecht, Netherlands, Kluwer Academic, 2001Google Scholar

31. Loeb PA: Independent Living Scales Manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, Harcourt Brace, 1996Google Scholar

32. Skoler DL, Allbright AL: Judicial oversight of the nation's largest guardianship system: caselaw on Social Security Administration representative payee issues. Mental and Physical Disability Law Reporter 24:169–174, 2000Google Scholar

33. Rosenheck RA, Neale MS: Therapeutic limit setting and six-month outcomes in a Veterans Affairs assertive community treatment program. Psychiatric Services 55:139–144, 2004Google Scholar

34. Elbogen EB, Wilder C, Swartz M, et al: Caregivers as money managers for adults with severe mental illness: how treatment providers can help. Academic Psychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar

35. Conrad KJ, Matters MD, Hanrahan P, et al: Representative payee for individuals with severe mental illness at Community Counseling Centers of Chicago. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 17:169–186, 1999Google Scholar

36. Elbogen EB, Soriano C, Van Dorn R, et al: Consumer views of representative payee use of disability funds to leverage treatment adherence. Psychiatric Services 56:45–49, 2005Google Scholar

37. Conrad KJ, Matters MD, Hanrahan P, et al: Characteristics of persons with mental illness in a representative payee program. Psychiatric Services 49:1223–1225, 1998Google Scholar

38. National Research Council Committee on Social Security Representative Payees, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education: Improving the Social Security Representative Payee Program: Serving Beneficiaries and Minimizing Misuses. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2007Google Scholar

39. Fraud and Abuse in the Supplemental Security Income Program. Washington, DC, Social Security Administration, 2004Google Scholar