Changes in the Process of Care for Medicaid Patients With Schizophrenia in Utah's Prepaid Mental Health Plan

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Changes in the process of psychiatric care received by Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia were examined after the introduction of capitated payments for enrollees of some community mental health centers (CMHCs) under the Utah Prepaid Mental Health Plan. METHODS: Data from the medical records of 200 patients receiving care in CMHCs participating in the prepaid plan were compared with data from the records of 200 patients in nonparticipating CMHCs, which remained in a fee-for-service reimbursement arrangement. Using the Process of Care Review Form, trained abstracters gathered data characterizing general patient management, social support, medication management, and medical management before implementation of the plan in 1990 and for three follow-up years. Using regression techniques, differences in the adjusted changes between third-year follow-up and baseline were examined by treatment site. RESULTS: By year 3 at the CMHCs participating in the plan, psychotherapy visits decreased, the probability of a patient's terminating treatment or being lost to follow-up increased, the probability of having a case manager increased, the probability of a crisis visit decreased (but still exceeded that at the nonplan sites), and the probability of treatment for a month or longer with a suboptimal dosage of antipsychotic medication increased. Only modest changes in the process of care were observed at the nonplan CMHCs. CONCLUSIONS: Change in the process of psychiatric care was more evident at the sites participating in the plan, where traditional therapeutic encounters were de-emphasized in response to capitation. The array of changes raises questions about the vigor of care provided to a highly vulnerable group of patients.

To encourage innovation in health care financing and delivery, the Health Care Financing Administration grants waivers permitting state Medicaid programs to implement managed care approaches. In 1990 the state of Utah requested and received a freedom-of-choice waiver that allowed the state to develop the Utah Prepaid Mental Health Plan. Three of Utah's 11 community mental health centers (CMHCs) elected to contract with the state to provide mental health services on a capitated basis (1,2).

Our evaluation of the plan involved three components: analysis of Medicaid claims data, in-person interviews, and review of CMHC medical records. We have previously reported on the economic consequences and the changes in utilization of care that resulted from the plan's implementation (3,4). In this paper we compare measures of the process of care for Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia who were served by CMHCs participating in the plan and receiving capitated payments and for Medicaid beneficiaries who were served by nonparticipating CMHCs receiving fee-for-service reimbursement.

Methods

Sample

A total of 1,660 adult Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia, age 18 and older, were identified through review of Utah Medicaid claims data covering the period from July 1988 through November 1990. Beneficiaries qualified for inclusion in the study if they had either one inpatient admission with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or two outpatient claims with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia and if they remained eligible for Medicaid in November 1990. Excluded were beneficiaries with schizophrenia who received no treatment for that illness from Medicaid providers in the period under review and those who became eligible for Medicaid after November 1990.

Experience from an evaluation of a Medicaid demonstration program in Minnesota indicated that review of claims data reliably generates a sample of beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Lurie and associates (5) reported that a diagnosis of schizophrenia could be confirmed through provider interviews for nearly 90 percent of their sample, which was identified using similar procedures.

All 1,660 cases identified were used in the claims' data analysis component of the evaluation of the Utah prepaid plan. For the in-person interview component, the goal was to collect baseline data on 800 individuals from which the medical records study sample would be drawn. The 800 cases were approximately evenly divided between those served by CMHCs in the plan, whose care was reimbursed on a capitated basis, and those served by nonplan CMHCs, whose care was reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis.

Because only a small number of the potential study subjects lived in the predominantly rural CMHC catchment areas, we attempted to contact all of them for interviews. In the urban CMHC areas, individuals were randomly selected for interviews. The final interview sample consisted of 823 subjects, of whom 378 were receiving services from CMHCs in the prepaid plan and 445 were receiving services from nonplan facilities.

An additional 244 individuals who were contacted did not complete the interview process or were excluded because they were minors, their psychotic or physical illness precluded participation, they were no longer Medicaid beneficiaries, they could not be located due to their moving out of Utah or to another location in the state, or they refused to participate. A total of 105 of these individuals were served by CMHCs in the plan, and 139 were served by nonplan sites.

For the medical records study, a sample of 200 cases from plan CMHCs and 200 cases from nonplan CMHCs was randomly selected from the interview sample. Medical records were abstracted for the baseline year, July 1990 through June 1991, and three follow-up years, 1991- 1992, 1992-1993, and 1993- 1994.

Data collection

To guide the collection of data from medical records at the CMHCs, we developed the Process of Care Review Form (6). This instrument was designed for use by trained abstracters to gather data characterizing the general management of the patient, social support, medication management, medical management, psychiatric assessment, and psychiatric hospitalization.

We used the form to collect data over the five-year study period to assess changes in the process of psychiatric care provided to the clients with schizophrenia in the sample. The form enables documentation of CMHC practice patterns and is a vehicle for gauging change that may result from shifts in reimbursement methods.

Research design

The basic approach employed in the analysis of the CMHC medical records data was a pre-post comparison with a contemporaneous control group. Given the process used by the state for selecting CMHCs to participate in the prepaid plan, we were concerned that the catchment areas of these facilities might be systematically different from other CMHC catchment areas in ways that we could not control for. If the evaluation had relied solely on cross-sectional comparisons of beneficiaries in the two groups, then the estimated effects of being in the group from the prepaid plan might have been biased because the comparisons might have been influenced by unknown site-specific factors.

Because we had data on patients that predated the plan's implementation, we could remove the effects of any stable time-invariant individual and catchment-area characteristics that might confound the results by allowing each patient to act as his or her own control (7). However, a risk in a simple pre-post study design is that the method might confound other concurrent changes with the shift to capitation. Employing a comparison group from areas not participating in the plan removed these concurrent trends from the estimated effect of being served by a CMHC participating in the plan.

We used regression analyses to examine differences between beneficiaries served by plan CMHCs and nonplan CMHCs. We calculated the difference in values for specific measures between two waves (the third-year follow-up value minus the baseline value) as the dependent variable for continuous measures. For the analysis of dichotomous measures, we used regression techniques to obtain predicted probability values, adjusting for baseline differences in the plan and nonplan groups. Part of the adjustment used in the analysis of both the dichotomous and the continuous measures involved obtaining the predicted value of the dependent variable if it was assumed that the entire sample was in the plan sector or the nonplan sector. In other words, the adjustment sought to answer the question, What would be the value of the dependent variable if the entire population received care in a CMHC that participated in the prepaid plan? Or conversely, if they received care in a nonparticipating CMHC? (A discussion of the statistical techniques used to generate these predicted values is available on request from the first author.)

Results

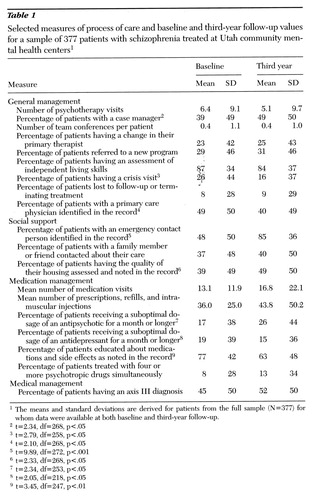

We examined 19 measures from the first four sections of the Process of Care Review Form. The section on psychiatric assessment was omitted because few patients received new assessments in the study interval. Likewise, the limited number of hospitalizations precluded examining this domain. Dichotomous measures were included in the analysis if there were enough responses in each cell to estimate the model. The measures correspond to events occurring from July 1 to June 30 of the respective study year and are defined in Table 1 together with both baseline and third-year follow-up values for the entire sample—that is, patients in the plan CMHCs and the nonplan CMHCs.

By year 3 of the plan's implementation, the participating CMHCs had time to complete the transition from fee-for-service to capitated payment for serving Medicaid beneficiaries. (Results of process measures including unadjusted values and adjusted differences for the baseline year and for each of the three follow-up years are available on request from the first author.)

Data from medical records were available for 377 patients in the sample for both baseline and year 3; data for 23 patients were deleted because the patients had no contact with their CMHC for one of these two study periods.

At baseline, several statistically significant differences were identified between the two groups, particularly with regard to general patient management. Patients in CMHCs in the plan were less likely than those in the nonplan facilities to have a case manager (31 percent versus 53 percent), their independent living skills were less likely to be assessed (82 percent versus 94 percent), and they were less likely to be lost to follow-up or to terminate treatment (6 percent versus 12 percent). Patients in the plan CMHCs were more likely than those in nonplan facilities to be referred to new programs (34 percent versus 22 percent) and to make a crisis visit to the CMHC (34 percent versus 16 percent).

At baseline, patients in plan CMHCs were less likely than those at nonplan sites to receive a suboptimal dosage of an antipsychotic for a month or longer (14 percent versus 22 percent) and more likely to receive a suboptimal dosage of an antidepressant for a month or longer (21 percent versus 15 percent).

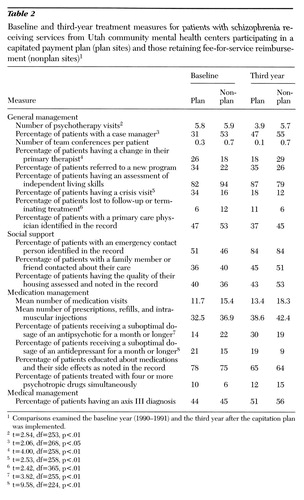

To determine if the population of Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia would have experienced a different pattern of care if all of them had received mental health services in nonplan CMHCs or in plan CMHCs, we compared the adjusted (for baseline differences) change between the third follow-up year and the baseline year for the nonplan CMHCs to the adjusted change between the third follow-up year and the baseline year for the CMHCs participating in the plan. It is this “difference of changes”that was used to determine if the experience of Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia was a function of the treatment site. Table 2 summarizes the results for the 19 measures.

The results for the dichotomous process measures are presented in terms of probabilities adjusted for baseline differences between patients in the capitated and noncapitated sectors. The adjusted probabilities are the probabilities if the entire sample received services in the noncapitated sector or the entire sample received services in the capitated sector. The analysis is done for the third follow-up year; the baseline year was 1990-1991.

Discussion

In this study four general areas of the Process of Care Form were examined: general patient management, social support, medication management, and medical management. In this section we discuss whether, for each of these areas, evidence was found that a more vigorous approach to the management of schizophrenia was provided at year 3 versus baseline in either the CMHCs that participated in the prepaid plan or the nonplan facilities.

The values presented in Table 1, both at baseline and year 3, for the total sample (N=377) provide an objective picture of the pattern of care rendered by CMHCs. To our knowledge, such data have not previously been reported as reference or anchor points. Quite apart from comparing care at plan and nonplan sites, these measures are instructive in their own right. To what extent such data from other states' CMHCs would be comparable is an open question.

We are fully cognizant of the limitations imposed on the analysis and on our interpretation of findings by the use of medical records data (8,9). For instance, some CMHCs may have more detailed protocols and requirements than others for what is to be recorded in the medical record. We also are aware that, taken individually, movements or differences in any single indicator may be open to different interpretations. By using a variety of indicators designed to reflect different aspects of patient care, using patients as their own controls, and comparing the differences in changes in the study measures, we have attempted to minimize the possibility of drawing conclusions that are unduly influenced by recording differences or ambiguities of interpretation.

General management

General management encompasses the frequencies of particular types of treatment, the establishment of treatment goals, assessment of the patient's condition, and measures of the stability of patient-therapist relationships. Given the variety of measures included under this heading, it is not surprising that the overall results about the impact of the capitated plan are mixed. At baseline at the plan CMHCs, less case management, less assessment of independent living skills, more referral to new programs, and more crisis visits were recorded than at nonplan sites. Also at baseline, patients at the plan sites were less likely to terminate treatment or be lost to follow-up. By the third year of implementation, evidence was found that service use had increased at the plan sites in some areas and decreased in others compared with the nonplan sites.

At year 3, the number of psychotherapy visits decreased at plan CMHCs, as did the probability of a crisis visit, while the use of case management increased. Less change in these measures was observed at the nonplan sites. Patients at the plan sites were less likely at year 3 than at baseline to experience a change in their primary therapist, whereas patients at the nonplan sites were more likely to experience this change. Conversely, the probability of a patient's terminating treatment or being lost to follow-up increased at the plan sites at year 3, while it decreased at the nonplan sites. No other significant differences between baseline and year 3 were found between the two cohorts for the remaining items in the general management domain.

Collectively, these observations indicate that at CMHCs participating in the plan, the general management of Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia de-emphasized traditional therapeutic encounters, increased reliance on case management, and led to greater numbers of patients being lost to follow-up than at the nonplan sites.

Social support

In contrast to general management, overall trends in social support seem much more consistent across the plan and nonplan sites. At baseline, indicators of attention to social support issues were similar for plan and nonplan facilities. For each indicator, an increase in attention to social support was noted at year 3 at both plan and nonplan sites, and relatively little difference between the two was evident in the third-year data. This finding likely reflects an increased appreciation of the importance of the social dimensions of mental health care, particularly for patients with schizophrenia.

Medication management

For patients with schizophrenia, decompensation and the resulting need for psychiatric hospitalization are most often explained as a function of the patient's noncompliance with neuroleptic medication. Accordingly, medication management may be the central element in care rendered to patients with schizophrenia.

Data from year 3 at both the plan and the nonplan CMHCs suggest an increased reliance on medication management compared with baseline. The number of medication visits and the number of prescriptions, refills, and intramuscular injections increased. For the nonplan sites at year 3, the mean number of medication visits per year was slightly more than 18, which roughly approximates a medication check at three-week intervals; the mean was 13 visits per year at the plan sites. Although the differences are numerically modest, five additional medication visits per year should create meaningful opportunities or options for the clinician. Alternatively, the greater number of visits at the nonplan sites could reflect the presence of patients with more variable presentations and clinical courses, requiring more vigorous attention.

The results pertaining to the use of suboptimal dosages of psychotropic medications are striking. At baseline, 22 percent of patients at the nonplan sites and 14 percent of patients at the plan sites were determined to be receiving inadequate dosages of antipsychotic medications. By year 3 this figure was 30 percent at the plan sites, which raises particular concerns. Although the number of medication visits and prescriptions increased, nearly a third of psychotropic dosages were judged suboptimal, exposing the patients to potential risks (side effects) with little or no likelihood of clinical gain. The inadequate dosages may reflect a greater reliance on nonphysicians and nonpsychiatrists for medication management at the plan CMHCs.

Judgments about suboptimal dosing were made in accord with a table of drug ranges derived from several reference sources in 1990, when the Process of Care Form was constructed. A recent article in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry's Expert Consensus Guideline Series confirms the continued appropriateness of the ranges (10). Although some of these values may be challenged or debated, the critical factor is that our criteria were applied uniformly to both the plan and the nonplan facilities, and differences were demonstrated. One criterion for suboptimal dosing required that the patient receive the low dosage for at least a month. The risks incurred in the use of suboptimal dosages are clear: lowering the dosage of neuroleptics too much exposes patients to a much higher risk of relapse or exacerbation of symptoms.

A number of patients with schizophrenia also received antidepressants, with sizable proportions receiving suboptimal dosages at baseline (15 percent in nonplan CMHCs and 21 percent in plan CMHCs). By year 3 the proportion receiving a suboptimal dosage decreased to a greater degree at the nonplan sites than at the plan sites. To the extent that antidepressants may have been used to treat panic symptoms or insomnia, these findings may be difficult to interpret. Regrettably, we did not address these considerations in our design of the medical record review.

Completing the medication management picture, use of multiple medications increased in year 3 at both the plan and the nonplan CMHCs, with bigger change occurring for nonplan patients. The use of polypharmacy appears to be an area in which both plan and nonplan sites failed to show improvement. At the outset, three-quarters of patients at both sites received education about medication usage and side effects. By year 3 these percentages had declined to about 65 percent. These activities may have decreased in importance because patients had received medication education in the past.

Medical management

Patients with schizophrenia are at risk for medical illness because of poor personal hygiene, nutrition, and self-care. Moreover, as a group they have a substantially increased mortality risk compared with the general population. This risk appears to involve both natural and unnatural causes (11). Comorbid medical conditions may exacerbate or intensify the course of schizophrenia. Vigorous care for patients with schizophrenia should include attention to their medical well-being. With this in mind, we endeavored to gauge the extent of medical care, as evidenced in records maintained by the CMHCs.

The records reflect comparable attention to axis III conditions at baseline. At year 3, attention increased by 12 percent at nonplan sites and by 6 percent at plan sites. Other measures of medical management that were examined included frequency of lithium level determinations, frequency of white cell counts for patients receiving clozapine, and frequency of other laboratory studies. Unfortunately, so few patients had such studies that meaningful comparisons were precluded. This finding, in itself, suggests less than vigorous attention to medical management at both plan and nonplan CMHCs.

Overall

By the third year, the plan sites had reduced their reliance on psychotherapy. Over the same period, attrition from therapy increased, and fewer changes of therapists were observed at these sites. There were fewer crisis visits compared with baseline, but the number of crisis visits at plan sites still exceeded those at nonplan sites. The number of medication visits increased slightly at plan CMHCs, although it should be noted that this increase was accompanied by an increase in the frequency of suboptimal neuroleptic dosages at plan sites. Attention to social support increased, but little focus was directed to medical care of these patients with schizophrenia.

Compared with plan sites, change at year 3 at nonplan sites was less pronounced. Use of case managers, number of team conferences, number of psychotherapy visits, and referral to new programs remained relatively stable at nonplan sites. No reduction was noted in reliance on psychotherapy, and, over the same period, a decrease in attrition from therapy and an increase in the number of individuals changing therapists were found. The number of crisis visits declined modestly at nonplan CMHCs, while increases were observed in medication visits, number of prescriptions, instances of multiple medication use, and attention to social support. General medical care received little attention, at least as was evident in medical records maintained by the CMHCs.

Conclusions

The data suggest that CMHCs modified their practice patterns in response to the introduction of a different payment mechanism. Fewer changes were seen at the nonplan sites, where fee-for-service reimbursement remained in effect.

What conclusions are to be drawn? Proponents of capitation will underscore how few of the process measures demonstrate that significant differences in the delivery of care followed the introduction of the plan. Moreover, they will note that changes in the process of care do not de facto lead to altered outcomes for patients. (The data at hand do not address outcomes as such.) Those who are opponents of capitation or skeptics will emphasize that the data point to inadequate neuroleptic coverage, increased attrition from treatment, continued reliance on crisis management, and the devaluing of traditional therapeutic treatment at the plan sites. They will argue that such changes must have a negative impact on patients and their courses.

From our viewpoint, only longitudinal data will afford a definitive answer. However, the data at hand should suffice to raise pointed concerns about the vigor of care provided to the most vulnerable of our patients in a capitated delivery system.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by National Institute of Mental Health grant MH-48998-03. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided by the Utah Department of Health's Health Care Financing Division and the community mental health centers in Utah.

Dr. Popkin, Dr. Lurie, and Mr. Callies are affiliated with the Hennepin County Medical Center, 701 Park Avenue, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55415. Dr. Popkin is chief of psychiatry and Mr. Callies is an administrative analyst in the department of psychiatry, and Dr. Lurie is a staff physician. Dr. Popkin is also professor of psychiatry and medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School, and Dr. Lurie is also professor of medicine and public health at the Institute for Health Services Research at the University of Minnesota. Dr. Manning is professor of economics in the department of health studies at the University of Chicago. Dr. Gray is director of the research and evaluation program at the Health Sciences Center at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Mr. Harman is a doctoral studentand Dr. Christianson is professor in the division of health services research and policy at the University of Minnesota.

|

Table 1. Selected measures of process of care and baseline and third-year follow-up values for a sample of 377 patients with schizophrenia treated at Utah community mental health centers1

1The means and standard deviations are derived for patients from the full sample (N=377) for whom data were available at both baseline and third-year follow-up.

2t=2.34, df=268, p<.05

3t=2.79, df=258, p<.05

4t=2.68, df=268, p<.05

5t=9.89, df=272, p<.001

6t=2.33, df=268, p<.05

7t=2.34, df=253, p<.05

8t=2.05, df=218, p<.05

9t=3.45, df=247, p<.01

|

Table 2. Baseline and third-year treatment measures for patients with schizophrenia receiving services from Utah community mental health centers participating in a capitated payment plan (plan sites) and those retaining fee-for-service reimbursement (nonplan sites)1

1Comparisons examined the baseline year (1990-1991) and the third year after the capitation plan was implemented.

2t=2.84, df=253, p<.01

3t=2.06, df=268, p<.05

4t=4.00, df=258, p<.01

5t=2.53, df=258, p<.01

6t=2.42, df=365, p<.01

7t=3.82, df=255, p<.01

8t=9.58, df=224, p<.01

1. Christianson JB, Gray DZ: What CMHCs can learn from two states' efforts to capitate Medicaid benefits. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:777-781, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Christianson JB, Manning W, Lurie N, et al: Utah's prepaid mental health plan: the first year. Health Affairs 14(3):160-172, 1995Google Scholar

3. Stoner T, Manning W, Christianson J, et al: Expenditures for mental health services in the Utah prepaid mental health plan. Health Care Financing Review, in press Google Scholar

4. Christianson J, Gray D, Kihlstrom LC, et al: Development of the Utah prepaid mental health plan. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research 15:117-135, 1995 Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lurie N, Moscovice J, Popkin M, et al: Accuracy of Medicaid claims for psychiatric diagnosis: experience with the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 54:69-71, 1992Google Scholar

6. Popkin MK, Callies AL, Lurie N, et al: An instrument to evaluate the process of psychiatric care in ambulatory settings. Psychiatric Services 48:524-527, 1997Link, Google Scholar

7. Campbell D, Stanley J: Experimental and Quasi Experimental Designs for Research. Chicago, Rand-McNally, 1965Google Scholar

8. Mattson MR (ed): Manual of Psychiatric Quality Assurance. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992Google Scholar

9. Romm FJ, Putnam SM: The validity of the medical record. Medical Care 19:310-315, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Treatment of Schizophrenia: Expert Consensus Guideline Series. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 12b):1-58, 1996Google Scholar

11. Simpson JC, Tsuang MT: Mortality among patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:485-499, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar