Off-Label Use of Second-Generation Antipsychotic Agents Among Elderly Nursing Home Residents

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines off-label use as use of an approved drug for treatment "that is not included in the product's approved labeling or statement of intended uses" ( 1 ). The FDA focuses on market entry of prescription drugs rather than controlling prescribing practices and thus allows off-label use of medications for indications beyond those formally evaluated by the manufacturer. Off-label prescribing of prescription medications is not illegal ( 2 ), is often believed to be supported by scientific evidence ( 3 ), and is commonplace in clinical settings ( 4 , 5 ). Although this practice offers the potential to use medications innovatively in clinical practice, it sometimes raises concerns about patient safety and costs.

Second-generation antipsychotics are antipsychotic agents approved by the FDA mainly for the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar mania ( 6 , 7 ). However, second-generation antipsychotic agents are commonly used in off-label indications such as for treatment of bipolar disorder, depression, and psychotic symptoms associated with dementia in the elderly population ( 6 , 7 , 8 ). Although the evidence base for off-label indications is limited, studies suggest that 43% to 70% of use of second-generation antipsychotic agents is off label ( 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ). In particular, second-generation antipsychotics have been extensively used off label for treatment of psychological and behavioral symptoms of dementia ( 12 , 13 ).

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) published a comparative review to examine the evidence for off-label use of second-generation antipsychotic agents as part of the Effective Heath Care Program initiated in 2005 ( 6 ). After conducting an extensive literature review, the AHRQ reported that the most frequent off-label uses of second-generation antipsychotics were for depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), personality disorders, Tourette's syndrome, autism, and agitation in dementia. For the analysis of efficacy and effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotic agents, 84 published placebo-controlled trials were reviewed. This systematic review found moderate strength of evidence for the efficacy of risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine in the treatment of behavioral problems in dementia; of olanzapine in the treatment of depression; and of risperidone and quetiapine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Few studies have examined the use of second-generation antipsychotic agents among U.S. nursing home residents, and little is known about off-label use and evidence-based use of second-generation antipsychotic agents in nursing homes. Previous studies have found up to 20% prevalence of second-generation antipsychotic use based on data collected until 2001 ( 13 , 14 ). Rosenheck and colleagues ( 12 ) reported that 42.8% of second-generation antipsychotic use was for off-label psychiatric indications. Chen and colleagues ( 7 ) showed that recipients of antipsychotics who were 65 or older were 5.2 times as likely to receive an off-label antipsychotic medication as those younger than 65 ( 7 ). This study examined the prevalence of off-label and evidence-based use of second-generation antipsychotic agents and factors associated with their off-label use among elderly nursing home residents.

Methods

Data source

This study was conducted by using cross-sectional data from the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey (NNHS) ( 15 ). The NNHS is a periodic nationally representative sample survey of U.S. nursing homes and their services, staff, and residents. It was conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to provide national data about providers and recipients of care in U.S. nursing homes. This study used the public-use data files from the 2004 NNHS to examine the off-label and evidence-based use of second-generation antipsychotics and factors associated with their off-label use. The study was approved by the University of Houston Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

The 2004 NNHS involved a stratified two-stage probability design. The first stage was the selection of facilities, and the second stage was the selection of residents. The 2004 NNHS consisted of resident and prescription data from 13,507 residents residing in 1,174 facilities for an overall response rate of 78%. The survey was conducted with computer-assisted personal interviews. It contained facility-level and resident-level modules. The facility-level module was completed by the interviewer before the resident-level modules were completed to confirm the eligibility of the facility for the survey. Facility data contained provider characteristics such as facility size, facility ownership, Medicare and Medicaid certification, services provided, specialty programs offered, and charges for services.

Data from the residents of the facility were collected by trained interviewers by consulting with the designated staff member familiar with a resident and his or her overall care. Residents were not contacted directly by the interviewers. Recipient data contained demographic characteristics, health status, diagnoses, medications taken by the recipient, services received by the recipient, and sources of payment. Prescription data included up to 25 medications administered in the 24 hours before the interview and up to 15 medications taken by the resident on a regular basis in the month before the interview but not taken in the prior 24 hours. Prescribed medications were coded for the products along with the generic ingredients according to a unique classification scheme developed at the NCHS, and drug classes were categorized by National Drug Code numbers ( 16 ).

The resident file captured up to 34 diagnostic conditions from the medical chart at the time of interview, including two primary diagnostic conditions at the time of admission to the nursing home, two current primary diagnostic conditions, and up to 30 current secondary diagnostic conditions. All diagnostic conditions were coded according to the ICD-9-CM . Further details concerning the data collection systems, sampling scheme, and definitions used in the NNHS can be found in other sources ( 15 , 17 ).

Study sample and definitions

The study sample included nursing home residents aged 65 and older who had received at least one prescription for a second-generation antipsychotic agent. Clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole were included. Because of a lack of data on drug regimen and duration, this study used an indication-based definition of off-label use. We considered all indications approved by the FDA for second-generation antipsychotic agents ( Table 1 ) ( 6 , 7 ). A second-generation antipsychotic prescription was classified as off label if none of the patient diagnoses ( ICD-9-CM codes) could be matched with an approved indication for a specific medication.

|

For the purpose of this study, second-generation antipsychotic prescriptions were classified as evidence based if one of the ICD-9-CM codes the patient received could be matched with an FDA-approved indication or an indication for which the AHRQ systematic review found at least moderate strength of evidence of effectiveness. Otherwise, such prescriptions were classified as non-evidence based. Table 1 lists the indications for which the AHRQ systematic review found at least moderate strength of evidence for the effectiveness of these agents. The AHRQ defined moderate strength as "Further research is likely to have an impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate" ( 6 ).

Analytical approach and statistical analysis

The resident file and prescription files were merged to examine person-level utilization data based on the unique identifier provided by the NCHS. Generic ingredient codes were used to identify second-generation antipsychotic agents for the analysis. The 2004 NNHS data resulted in an unweighted sample of 11,939 elderly nursing home residents, 2,737 (22.9%) of whom received second-generation antipsychotic medications. The national estimates were derived for these records on the basis of the inflation factor (sampling weight) provided by the NCHS. The diagnoses defined by ICD-9-CM codes of recipients of a second-generation antipsychotic as recorded in the resident file of the 2004 NNHS were used to determine off-label and evidence-based use. ICD-9-CM definitions of indications were identified through comprehensive literature review and the ICD-9-CM database.

The 2004 NNHS data are based on a complex probability survey design. The 2004 NNHS provided cluster and strata variables to account for design effects of stratification and the cluster. The survey design variables were incorporated in descriptive and multivariate analyses in SAS survey procedures to accommodate the complex design of the NNHS. Survey procedures such as SURVEYFREQ and SURVEYMEANS were used for descriptive domain analysis.

Multiple logistic regressions using the SURVEYLOGISTIC procedure were used to identify the patient and facility factors associated with off-label use of second-generation antipsychotic drugs among elderly nursing home residents. The analytical sample was 2,605 for multivariate analysis because of missing data for 132 residents. The dependent variable was dummy-coded off-label use of second-generation antipsychotic agents, and the independent variables were patient and facility characteristics. Patient and facility characteristics associated with off-label use were selected on the basis of the literature review and availability from the data source. Patient characteristics included demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, and ethnicity), payment source (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, and self-pay), and diagnoses (schizophrenia, bipolar mania, dementia, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, and personality disorder). Facility characteristics included ownership, available beds, and metropolitan statistical area.

The ICD-9-CM codes were used to group diagnoses, such as schizophrenia (295.XX), bipolar mania (296.0X, 296.1X, 296.4X–295.8X), dementia (290.XX, 291.2X, 294.XX, 331.XX, 046.1X, or 046.3X), depression (296.2X–296.3X, 300.4X, 296.2X, 296.3X, or 311.XX), obsessive-compulsive disorder (300.3X), PTSD (309.81), and personality disorder (301.XX) ( 7 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ). We created modified weight variables as recommended by the NCHS ( 22 ) to conduct multivariate analysis of data from elderly residents by subgroup. The NCHS methodology involves the use of a sampling weight for the subpopulation of interest and near zero weight for observations that do not belong to the subpopulation. Statistical significance was defined as <.05.

Results

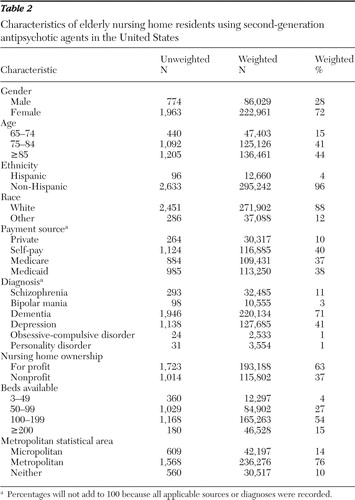

According to the 2004 NNHS, a total of 1,317,205 elderly persons resided in U.S. nursing homes. The analysis of prescription data revealed that 308,990 (23.5%) received at least one second-generation antipsychotic prescription. Table 2 shows the characteristics of those using these agents. Most elderly nursing home residents who received second-generation antipsychotic agents were female (72%), non-Hispanic (96%), and white (88%). Most resided in for-profit nursing homes (63%), in homes with a capacity of 100–199 beds (54%), and in homes located in a metropolitan area (76%). Seventy-one percent had dementia, and 41% had depression.

|

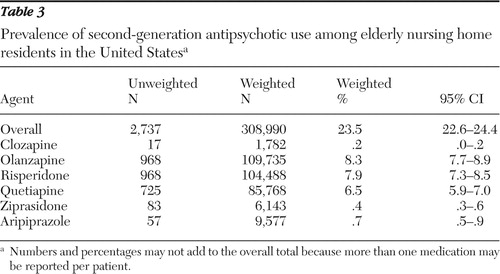

Table 3 shows the prevalence of second-generation antipsychotic use in the nursing homes studied; 23.5% of elderly nursing home residents received second-generation antipsychotic agents. Olanzapine was the most commonly prescribed agent (8.3%), followed by risperidone (7.9%) and quetiapine (6.5%). Table 4 shows the prevalence of off-label use. Among recipients of these agents, 86.3% received them for off-label indications during the study period. Off-label use was most prevalent for quetiapine (91.7%), risperidone (87.9%), ziprasidone (86.4%), and olanzapine (82.7%). Of the recipients of second-generation antipsychotics, 56.9% received them for indications that were classified as evidence based during the study period. This includes FDA-approved indications and indications for which AHRQ found moderate strength of evidence. Evidence-based use was most prevalent for olanzapine (77.3%), risperidone (76.0%), and aripiprazole (40.7%). Quetiapine was least used (8.9%) for evidence-based indications.

|

|

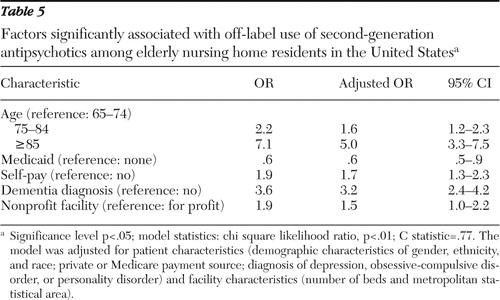

Table 5 shows the results of multiple logistic regressions with crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) along with 95% confidence intervals for receiving second-generation antipsychotic agents for an off-label use. Patient characteristics associated with off-label use included age, payment source, and diagnosis. Age was positively associated with off-label use. Patients aged 75 to 84 (OR=1.6) and those 85 years and older (OR=5.0) were more likely to receive second-generation antipsychotic agents for off-label indications than those aged 65 to 74. Medicaid was negatively associated (OR=.6) and self-pay was positively associated (OR=1.7) with off-label use. Those with diagnoses of dementia were 3.2 times more likely than those without dementia to receive these agents off label. Among the facility characteristics, only ownership was associated with off-label use. Nonprofit status was 1.5 times more likely than for-profit status to be associated with off-label use.

|

Discussion

According to the 2004 NNHS, 23.5% of elderly nursing home residents received second-generation antipsychotic medications. In comparison with the prevalence (8.5%) reported by Liperoti and colleagues ( 14 ) and based on U.S. regional data from five states in 1999–2000, this study found increased use of second-generation antipsychotic agents. However, findings from this study are consistent with the results of a national study conducted by Briesacher and colleagues ( 23 ) and based on the 2000–2001 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey; they found a prevalence of 20.3%. Overall, the findings suggest that antipsychotic use in nursing homes has remained stable since 2000.

This study found that 86.3% of those who received second-generation antipsychotics did so for indications that were off label during the study period. This rate is somewhat higher than those in previous studies that examined the extent of off-label use of second-generation antipsychotics in different settings. Rosenheck and colleagues ( 12 ) found that 47.2% of recipients of antipsychotics received second-generation agents for indications other than schizophrenia. Chen and colleagues ( 7 ) found that 63.6% of the recipients of antipsychotics aged 18 or older received at least one antipsychotic agent for an off-label indication. Data from inpatient practice during 2001–2003 in Italy revealed 50% of second-generation antipsychotic use to be off label ( 11 ). Furthermore, Leslie and colleagues ( 24 ) found that in 2007, antipsychotic agents prescribed to U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs patients were for off-label use in 60.2% of cases. Overall, the study findings suggest possible higher off-label use of antipsychotic agents in long-term care than in other settings.

In this study, six out of seven elderly patients who received second-generation agents did so for indications that were off label during the study period. This may be due to pharmaceutical promotion, growing scientific support, and prescribers' training and personal experience. The FDA allows prescribers to use available drugs, biologics, and devices according to their best knowledge and judgment. Occasionally, off-label use is indispensable and necessary, but it calls for increased responsibility in terms of ensuring that the prescribed agents are used safely. There is a need to be cautious in using second-generation antipsychotic agents for elderly patients in the light of recent safety concerns. Because data suggest that the risk of considerable adverse effects may offset the benefits of these agents in behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, prescribers should use caution ( 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ).

This study also found that almost 57% of the second-generation antipsychotics prescribed were for FDA-approved indications or indications for which AHRQ found moderate strength of evidence during the study period. Olanzapine and risperidone were highly used for indications approved by FDA (83% and 88%, respectively) or those denoted by the AHRQ as evidence based (77% and 76%, respectively). A cross-sectional analysis by Randley and colleagues ( 31 ) of nationally representative data from the 2001 IMS Health National Disease and Therapeutic Index (NDTI) showed that 66% of risperidone use had little or no scientific support. The variation in study findings may be due to differences in study populations. The NDTI included all age groups, whereas our study was limited to elderly nursing home residents. Overall the study findings revealed that 43% of the use of second-generation antipsychotics was without strong scientific support, suggesting a less than optimal quality of care in nursing homes ( 14 ); this utilization pattern also raises concern about safety issues with these agents, specifically in the elderly population.

The results of multiple logistic regression indicated that patient and facility characteristics were associated with second-generation antipsychotic use for off-label indications. With respect to facility characteristics, the study found that nonprofit status was more likely than for-profit status to be associated with off-label use. This finding is consistent with studies that found variation in antipsychotic prescribing rates among nursing homes across indications ( 32 ). With regard to patient characteristics, the study showed that the odds of receiving second-generation antipsychotic agents off label among elderly nursing home residents increased with age. Elderly residents 75 years and older were more likely than those 65–74 years to receive these agents for off-label indications. This may be attributed to age-related behavioral and psychological symptoms that were not captured in the disease or behavioral characteristics.

Elderly residents with Medicaid health insurance were less likely than those without Medicaid to receive second-generation antipsychotic agents for off-label indications, and residents paying out of pocket were more likely than other elderly residents to receive these agents for off-label indications. These differences could be attributed to formulary management and other administrative initiatives that are more prevalent among Medicaid patients than among patients who pay out of pocket. With respect to diagnosis, elderly residents diagnosed as having dementia were 3.2 times more likely to receive these agents for off-label indications than residents with no diagnosis of dementia. Leslie and colleagues ( 24 ) also found that veterans with diagnoses of organic brain syndromes or Alzheimer's disease were more than eight times as likely to receive quetiapine or risperidone off-label as those without these diagnoses. This finding can be explained by the prevalence of behavioral and psychological symptoms among dementia patients. Although the use of these agents for dementia is considered off label, there is moderate evidence to support their usage ( 6 ). Descriptive analysis revealed that 57% of second-generation antipsychotic use was for FDA-approved indications or indications for which AHRQ found moderate strength of evidence. The study findings suggest that although second-generation antipsychotics were frequently used for off-label indications, most of the usage was evidence based among elderly nursing home residents.

Although the AHRQ report revealed moderate strength of evidence for use of selected second-generation antipsychotic agents to treat dementia ( 6 ), recent clinical trials suggest limited benefits. The Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness in Alzheimer's Dementia study revealed that there was no advantage of second-generation antipsychotics over placebo because of adverse events ( 33 ). Median time to discontinuation of treatment because of lack of efficacy was longer with risperidone and olanzapine than with placebo and quetiapine. The time to discontinuation of treatment because of intolerability or adverse events was longer with placebo. Moreover, serious concerns about the safety of second-generation antipsychotics in treating behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia led the FDA to issue warnings about an apparent increased risk of mortality with these antipsychotic agents ( 34 ). In light of recent safety and efficacy data, clinicians need to optimize second-generation antipsychotic use among elderly patients.

The finding that over 40% of second-generation antipsychotic use was not evidence based is concerning and emphasizes the need for additional research in this area. Furthermore, increasing concern about the safety of prescribing these agents to elderly patients ( 6 , 34 ) underscores the urgent need to address the evidence base in regard to this vulnerable population. A recent quantitative model for prioritizing research on off-label medication use has ranked quetiapine a top priority for future research; risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole were all ranked in the top 15 ( 35 ). The model was based on the volume of medication use not supported by adequate evidence, potential for adverse effects, and a factor incorporating cost, time since regulatory approval for marketing, how long a drug has been approved for use, and the extent to which a drug is promoted. This model provides further evidence that research to expand the evidence base for second-generation antipsychotic prescribing for dementia and for other indications is urgently needed.

This study has several limitations. The findings are limited to the definitions of off-label and evidence-based use, data source, and the year in which the NNHS was conducted. This study used an indication-based definition of off-label and evidence-based use. Only FDA-approved indications were considered as approved indications in this study, and use of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of indications other than FDA-approved indications was considered off label. Evidence-based use was defined according to the results of a systematic review of literature by the AHRQ. Although there are other sources of evidence, this study used the AHRQ report because the NNHS data collection and the literature reviewed in the AHRQ report involved the same time frame. This study used ICD-9-CM codes to identify diagnoses in classifying off-label and evidence-based use.

Various patient and facility characteristics used in multivariate analyses were limited to those available from the data source. The cross-sectional multivariate analysis examined only associations, and not causal relationships, between the variables and off-label use. The inherent disadvantages of using secondary data, such as difficulty in assessing accuracy because of errors in data collection, editing, and imputation, were also limitations of this study. The research findings could be affected by both sampling error and sources of nonsampling error, which include nonresponse bias, respondent reporting errors, and interviewer effects. Also, the national estimates based on small subsamples could affect the confidence level of estimates and thereby reduce their reliability.

Conclusions

According to the 2004 NNHS, 86% of second-generation antipsychotic agents prescribed to elderly nursing home residents were for off-label indications and 57% of second-generation antipsychotic use was evidence based during the study period. Multivariate analysis found that both patient characteristics, such as age, payment source, and diagnosis, and facility characteristics, such as type of nursing home, were associated with off-label use. Overall, the study suggests that although second-generation antipsychotic agents were often used for off-label indications, most of the usage was evidence based. However, the high level of non-evidence-based use combined with recent safety and efficacy data suggest an urgent need to optimize the use of second-generation antipsychotics in the elderly population. Additional research is urgently needed to evaluate the evidence base concerning use of second-generation antipsychotics in treating dementia.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Good Reprint Practices for the Distribution of Medical Journal Articles and Medical or Scientific Reference Publications on Unapproved New Uses of Approved Drugs and Approved or Cleared Medical Devices. Rockville, Md, US Food and Drug Administration, 2009. Available at www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm12126.htm Google Scholar

2. Appler WD, McMann GL: View from the nation's capital: "off-label" uses of approved drugs: limits on physicians' prescribing behavior. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 9:368–370, 1989Google Scholar

3. Chavey WE II, Blaum CS, Bleske BE, et al: Guideline for the management of heart failure caused by systolic dysfunction: II. treatment. American Family Physician 64:1045–1054, 2001Google Scholar

4. Chen H, Deshpande AD, Jiang R, et al: An epidemiological investigation of off-label anticonvulsant drug use in the Georgia Medicaid population. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 14:629–638, 2005Google Scholar

5. Loder EW, Biondi DM: Off-label prescribing of drugs in specialty headache practice. Headache 44:636–641, 2004Google Scholar

6. Shekelle P, Maglione M, Bagley S, et al: Comparative Effectiveness of Off-Label Use of Atypical Antipsychotics: Comparative Effectiveness Review No 6. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research, Jan 2007. Available at effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/repFiles/Atypical_Antipsychotics_Final_Report.pdf Google Scholar

7. Chen H, Reeves JH, Fincham JE, et al: Off-label use of antidepressant, anticonvulsant, and antipsychotic medications among Georgia Medicaid enrollees in 2001. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:972–982, 2006Google Scholar

8. Glick ID, Murray SR, Vasudevan P, et al: Treatment with atypical antipsychotics: new indications and new populations. Journal of Psychiatric Research 35:187–191, 2001Google Scholar

9. Verma SD, Davidoff DA, Kambhampati KK: Management of the agitated elderly patients in the nursing home: the role of the atypical antipsychotics. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(suppl 19):50–55, 1998Google Scholar

10. Daniel DG: Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis and agitation in the elderly. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(suppl 14):49–52, 2000Google Scholar

11. Barbui CC, Nose NP, Stegagno M, et al: Off-label and non-classical prescriptions of antipsychotic agents in ordinary in-patient practice. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109:275–278, 2004Google Scholar

12. Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sernyak M: From clinical trial to real-world practice: use of atypical antipsychotic medication nationally in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Medical Care 39:302–308, 2001Google Scholar

13. Lee PE, Gill SS, Freeman M, et al: Atypical antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: systematic review. BMJ 75:329–333, 2004Google Scholar

14. Liperoti R, Mor V, Lapane KL, et al: The use of atypical antipsychotics in nursing homes. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:1106–1112, 2003Google Scholar

15. National Nursing Home Survey Documentation. Available at ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NNHS/nnhs04 . Accessed July 18, 2008 Google Scholar

16. Koch H, Campbell WH: The collection and processing of drug information. National Centerfor Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics Series 2(90):1–90, 1982Google Scholar

17. National Nursing Home Survey: Public-Use Data Files. Available at ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Datasets/NHS/nnhs04 . Accessed June 12, 2008 Google Scholar

18. Gruber-Baldini AL, Stuart B, Zuckerman IH, et al: Treatment of dementia in community-dwelling and institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 55:1508–1516, 2007Google Scholar

19. Sclar DA, Robison LM, Gavrun C, et al: Hospital length of stay for children and adolescents diagnosed with depression: is primary payer an influencing factor? General Hospital Psychiatry 30:73–76, 2008Google Scholar

20. McLaughlin T, Geissler EC, Wan GJ: Comorbidities and associated treatment charges in patients with anxiety disorders. Pharmacotherapy 23:1251–1256, 2003Google Scholar

21. Touré JT, Brandt NJ, Limcangco MR, et al: Impact of second-generation antipsychotics on the use of antiparkinson agents in nursing homes and assisted-living facilities. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy 4:25–35, 2006Google Scholar

22. Continuous NHANES Web Tutorial: Logistic Regression. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/NHANES/NHANESAnalyses/LogisticRegression/logistic_regression_intro.htm . Accessed July 18, 2008 Google Scholar

23. Briesacher BA, Limcangco MR, Simoni-Wastila L, et al: The quality of antipsychotic drug prescribing in nursing homes. Archives of Internal Medicine 165:1280–1285, 2005Google Scholar

24. Leslie DL, Mohamed S, Rosenheck RA: Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. Psychiatric Services 60:1175–1181, 2009Google Scholar

25. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al: Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. New England Journal of Medicine 360:225–235, 2009Google Scholar

26. Carson S, McDonagh MS: A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of atypical antipsychotics in patients with psychological and behavioral symptoms of dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 54:354–361, 2006Google Scholar

27. Gill SS, Bronskill SE, Normand ST: Antipsychotic drug use and mortality in older adults with dementia. Annals of Internal Medicine 146:775–786, 2007Google Scholar

28. Ballard C, Waite J, Birks J: Atypical antipsychotics for aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1:CD003476, 2006Google Scholar

29. Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel PS: Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 294:1934–1943, 2005Google Scholar

30. Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS: Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 14:191–210, 2006Google Scholar

31. Randley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS: Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Archives of Internal Medicine 166:1021–1026, 2006Google Scholar

32. Rochon PA, Stukel TA, Bronskill SE, et al: Variation in nursing home antipsychotic prescribing rates. Archives of Internal Medicine 167:676–683, 2007Google Scholar

33. Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al: Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer's disease. New England Journal of Medicine 355:1525–1538, 2006Google Scholar

34. Deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. FDA Public Health Advisory. Silver Spring, Md, US Food and Drug Administration, May 2009. Available at www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm053171.htm Google Scholar

35. Walton SM, Schumock GT, Lee KV, et al: Prioritizing future research on off-label prescribing: results of a quantitative evaluation. Pharmacotherapy 28:1443–1452, 2008Google Scholar