Health and Social Characteristics of Homeless Adults in Manhattan Who Were Chronically or Not Chronically Unsheltered

Despite evidence that nearly half (44%) of the homeless population in the United States is unsheltered or "street homeless" ( 1 ), previous research on homelessness has been based almost exclusively on samples obtained through shelter locations. Under new requirements by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), jurisdictions must count unsheltered homeless individuals in order to apply for HUD funds. Most of these enumeration efforts do not include interview components, and few gather data beyond basic demographic characteristics.

Even though the federal government has prioritized targeting of permanent housing resources to people who experience chronic homelessness, little research has been done on their distinguishing characteristics ( 2 ). Studies of the unsheltered homeless population have examined such topics as predictive factors ( 3 ), street outreach effectiveness ( 4 ), and approaches to service delivery ( 5 ). Little research has focused specifically on homeless persons who are chronically unsheltered ( 2 ). A better understanding of this population should help inform resource allocation and service delivery, enhancing efforts to reduce or eliminate homelessness in the United States. The study reported here attempted to partially fill these gaps in one large urban area, the borough of Manhattan in New York City.

Methods

A brief, closed-ended questionnaire was developed as part of an intake interview for a service registry database. Twenty-one short-term contractors and 48 permanent street outreach staff members were trained to use this questionnaire to conduct brief, closed-ended interviews with unsheltered homeless adults. Contractors included bilingual speakers of Spanish, Russian, Mandarin, and Creole who were assigned to neighborhoods known to accommodate their respective linguistic communities.

During August 2007, between the hours of 5:30 and 7:30 a.m., pairs of interviewers made a single, comprehensive pass through all Manhattan streets, parks, publicly accessible outdoor areas, and transit hubs other than subways. Every adult found bedded down, or perceived by the interviewer to be potentially homeless, was approached and asked to participate in the intake interview. Once it was confirmed that an individual had slept without shelter the previous night, he or she was offered $10 to participate.

A total of 511 individuals (30% of the 1,699 persons who were approached) refused to speak with the project interviewers. Interviewers' visual impressions of gender, race, and chronicity of homelessness (for example, extremely unkempt appearance or heavily laden shopping carts) were recorded for all nonrespondents, to examine possible response bias. Interviews were completed with 1,188 individuals. After participants interviewed more than once were identified and duplicated data were removed, 1,106 unduplicated interviews remained for analysis. A total of 1,093 interviews had sufficient information to determine whether the respondent was chronically unsheltered, according to the definition of "street chronicity" of the New York City Department of Homeless Services [NYCDHS]: sleeping without shelter at least nine of the previous 24 months ( 6 ). Because interviews were conducted to support direct delivery of outreach and housing placement services, documentation of informed consent was not obtained, on the advice of counsel. After the interviews were completed and the results distributed to service providers, use of the deidentified data for research purposes was ruled exempt by the institutional review board of the Center for Urban Community Services.

Between-group differences on continuous variables were evaluated with two-tailed t tests. Differences on nominal and dichotomous variables were evaluated by using chi square tests. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 14.0.2 for Windows.

Results

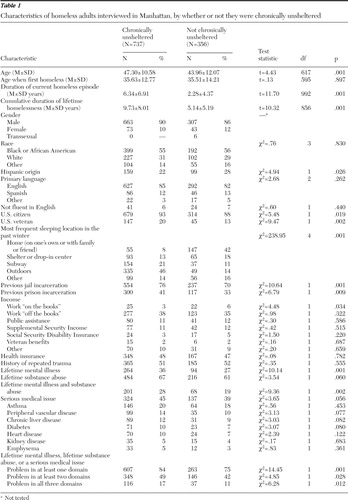

Sixty-seven percent (N=737) of the 1,093 unsheltered homeless persons interviewed were found to be chronically unsheltered, and 33% (N=356) were not. Table 1 presents data on characteristics of the two groups. Chronically unsheltered homeless persons were less likely than those who were not chronically unsheltered to be Hispanic (odds ratio [OR]=.72, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.54–.96). The chronically unsheltered population was significantly older (mean±SD difference 3.34±.75 years, 95% CI=1.86–4.82), with a larger proportion of veterans (OR=1.76, CI=1.22–2.52).

|

The homelessness histories of the two groups also significantly differed. The current episode of homelessness was longer for the chronically unsheltered group (mean difference 4.06±.35 years, CI=3.38–4.74), and individuals in this group also had longer histories of homelessness (mean difference 4.59±.45 years, CI=3.71–5.49). A larger proportion of the chronically unsheltered group had spent most of the last winter outdoors, in subway areas, and in shelter or drop-in centers (80% [N=582] compared with 43% [N=151]; OR=5.08, CI=3.86–6.69). Nearly half of those who were not chronically unsheltered (42%, N=147) had spent most of the previous winter in a home (OR=.11, CI=.08–.16). A smaller proportion of the chronically unsheltered group reported that they were currently working "on the books" (OR=.54, CI=.30–.96), although slightly more than a third of both groups reported currently receiving work income from "off the books" employment ( Table 1 ).

The chronically unsheltered group also had significantly higher rates of incarceration in jail (OR=1.59, CI=1.20–2.10) and prison (OR=1.42, CI=1.09–1.86), although the rates of incarceration were high for both groups. The chronically unsheltered group had higher rates of self-reported lifetime mental illness, defined as either a history of psychiatric hospitalization or current mental health counseling or treatment (OR=1.57, CI=1.19–2.08). They also had higher rates of both lifetime mental illness and lifetime substance abuse (substance abuse was defined as either receipt of substance abuse treatment or problems with substance use) (OR=1.62, CI=1.19-2.21). They were more likely to report a problem in one of the three health domains—a mental health problem, a substance abuse problem, or a serious medical issue (OR=1.82, CI=1.33–2.49)—and also to report problems in two of the three health domains (OR=1.34, CI=1.03–1.73). A larger proportion of the chronically unsheltered group reported problems in all three health domains (OR=1.65, CI=1.11–2.45). This group also had higher proportions of persons with lifetime substance abuse (OR=1.29, CI=.99–1.67) and with a serious medical issue (OR=1.29, CI=.99–1.67), but the differences were not significant. Very high self-reported rates of lifetime substance abuse and a serious medical issue were observed in both groups. Although the differences were not significant, rates of some serious medical conditions were higher in the chronically unsheltered group, including peripheral vascular disease (OR=1.44, CI=.96–2.17), chronic liver disease (OR=1.46, CI=.95–2.25), and diabetes (OR=1.54, CI=.95–2.52).

The chronically unsheltered group had low overall rates of entitlements (income and public health insurance), given their rates of serious health problems; however, the entitlement rates did not differ between the two homeless groups. About half of the respondents in both groups reported a history of repeated trauma.

As noted, 30% of individuals approached refused to be interviewed. Although we are unaware of any published studies that have reported refusal rates for street interviews, this figure is virtually identical to the rate (29%) obtained in a follow-up interview effort conducted in 2008 in the same area that used the same methods (Center for Urban Community Services, 2008, unpublished data). Our response rate is also consistent with those reported for street surveys conducted in 2008 in targeted areas of Los Angeles (74%) and New Orleans (79%), which used similar methods but included a second approach to individuals who initially refused to be interviewed (Common Ground, 2008, unpublished data).

The study interviewers reported that the proportion of women in the nonrespondent group (16%, N=72) was significantly larger than in the study sample (11%, N=117) ( χ2 =8.45, df=1, p=.004). The proportion of chronically unsheltered persons was also larger in the nonrespondent group (77%, N=388) than in the study sample (67%, N=737) ( χ2 =14.19, df=1, p<.001). Finally, the nonrespondent group had a significantly smaller proportion of African Americans (46%, N=206) than the study sample (55%, N=603) ( χ2 =8.84, df=1, p=.003). These differences suggest a substantial response bias.

In addition to the potential sources of bias described above, interviewers presumably also failed to locate or approach a certain number of unsheltered homeless individuals. Recent research suggests that 15%–29% of the unsheltered population may be missed by traditional street surveys ( 7 ), which would introduce another possible source of bias.

Discussion

The results show that homeless adults in Manhattan—whether or not they are chronically unsheltered—have high rates of health problems, including mental illness, substance abuse, and serious medical conditions. Eighty percent of respondents reported problems in at least one of these areas, and 45% reported problems in at least two. In response to a single, yes-no question, half of the respondents reported a history of repeated trauma.

However, the homeless individuals who were chronically unsheltered were distinct from those who were not. Primarily, they were older and were more likely to be a veteran and to have a more extensive history of homelessness. Those who were chronically unsheltered were also less likely to be Hispanic, which may be associated with the "Latino paradox" of homelessness ( 8 ), a complex topic beyond the scope of this report. The respondents who were chronically unsheltered had been homeless for an average of nearly ten years. Despite these extensive histories of serious health problems and victimization, few respondents in the chronically unsheltered group had accessed entitlement income, and slightly less than half had health insurance.

Conclusions

The very sick and aged nature of the unsheltered homeless population suggests that more aggressive efforts should be undertaken to enroll unsheltered homeless people, particularly those who are chronically unsheltered, in income and health benefits and to create adequate housing opportunities with appropriate support services. Such efforts may ameliorate homelessness, its associated trauma, and the severe negative health consequences of living in outdoor locations.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Third Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress. Washington, DC, US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development, July 2008. Available at www.hudhre.info/documents/3rdHomelessAssessmentReport.pdf Google Scholar

2. Caton CLM, Wilkins C, Anderson J: People who experience long-term homelessness: characteristics and interventions, in Toward Understanding Homelessness: The 2007 National Symposium on Homelessness Research. Edited by Dennis D, Locke G, Khadduri J. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Sept 2007. Available at aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/homelessness/symposium07/index.htm Google Scholar

3. Early DW: An empirical investigation of the determinants of street homelessness. Journal of Housing Economics 14:27–47, 2005Google Scholar

4. Lam JA, Rosenheck R: Street outreach for homeless persons with serious mental illness: is it effective? Medical Care 37:894–907, 1999Google Scholar

5. Shern DL, Tsemberis S, Anthony W, et al: Serving street-dwelling individuals with psychiatric disabilities: outcomes of a psychiatric rehabilitation clinical trial. American Journal of Public Health 90:1873–1878, 2000Google Scholar

6. Request for Proposals to Provide Street Homeless Outreach and Housing Placement Services. PIN no 071-07S-03-1076. New York, New York City Department of Homeless Services and Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2006Google Scholar

7. Hopper K, Shinn M, Laska E, et al: Estimated numbers of unsheltered homeless people through plant-capture and postcount survey methods. American Journal of Public Health 97:1438–1442, 2007Google Scholar

8. Conroy SJ, Heer DM: Hidden Hispanic homelessness in Los Angeles: the "Latino paradox" revisited. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 25:530–538, 2003Google Scholar