Understanding Service Disengagement From the Perspective of Case Managers

Disengagement from services by people with severe mental illnesses has been a challenge for the mental health system since deinstitutionalization ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). Among the hardest to reach and retain in services are adults experiencing homelessness and mental illnesses with co-occurring substance abuse, a group for which trust building is considered essential to successful engagement ( 7 ). These consumers often find themselves on the "institutional circuit," moving between the streets, shelters, hospitals, and jails, which results in sporadic and uncoordinated encounters with mental health care providers ( 8 ).

Case managers, as frontline providers, are charged with the task of retaining hard-to-engage consumers in services. With the recovery movement, the emphasis has shifted toward supporting consumer choice and using the relationship to engage consumers rather than using coercive strategies ( 9 , 10 ). The evidence-based practice referred to as integrated treatment has replaced confrontational approaches with the use of techniques such as motivational interviewing when working with consumers with co-occurring disorders ( 11 ). However, these approaches are frequently thwarted by premature disengagement from services. Given this reality, it is important to consider how case managers handle situations in which these clinical relationships do not go as planned or end abruptly. This study sought to understand how providers make sense of consumer disengagement.

Research has shown that consumers reject services on the basis of a desire to be independent, a lack of active participation in services, poor therapeutic relationships, lack of provider cultural competence, and side effects from medication ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). For homeless persons with co-occurring disorders, barriers to engagement include illicit drug use, lack of one-on-one attention, and program restrictions ( 15 ). Whether case managers concur with consumers about the causes of disengagement is not clear. Research has demonstrated significant differences in case manager and consumer perceptions, both in terms of the clinical relationship and service needs ( 16 , 17 , 18 ). Whether case managers attribute disengagement to the failure of the relationship, consumer behaviors, or the inadequacies of their program affects how they perceive their effectiveness as professionals and their ability to succeed with future consumers.

Given the premium placed on clinical relationships ( 19 ), case managers may perceive disengagement as a personal rejection. Providers can experience feelings of anger, guilt, dislike, and disappointment when confronted with a consumer who does not conform to service expectations. However, providers sometimes respond to problem behaviors by labeling consumers as "difficult," thus assigning blame to the consumer and absolving providers from feelings of incompetence ( 20 , 21 , 22 ). Such labels are socially constructed and can promote more "difficult" behaviors by the consumer, who acts in accordance to the imposed label.

Case managers may also employ "practice wisdom," using past experience to predict and anticipate consumer behavior. Researchers have shown how workers within organized settings employ schemas, a cognitive process by which the acquisition, encoding, and recall of information inform future inferences and action ( 23 , 24 ). Although schemas can be useful in simplifying complex events and can differentiate between novice and expert ( 25 , 26 ), they can also lead to errors in judgment ( 27 ). Case manager schemas that anticipate negative behaviors could preclude a sense of hope and optimism about the consumer's future, which are essential to providing recovery-oriented services. Optimism about consumer outcomes, which has been found to be associated with positive consumer-provider social interactions, may be challenging in settings with high rates of disengagement ( 28 ).

This qualitative study analyzed the perspectives of 18 case managers on 29 cases of service disengagement by their consumers. Using in-depth interviews, the case managers' retrospective accounts were analyzed to understand their attributions and responses to the consumers' disengagement. Where available, the study also compared these accounts with predisengagement (baseline) interviews and with consumers' postdeparture residential status.

Methods

Sampling

This study sampled 18 case managers working with 29 consumers who disengaged from services during the course of a longitudinal study that followed 83 new enrollees from four programs for homeless adults with co-occurring disorders in New York City ( 15 ). One program used a housing-first approach that provides immediate access to independent apartments along with assertive community treatment ( 29 ). The other three programs used a traditional approach that consists of congregate residential settings and on-site services with an opportunity to graduate to independent apartment living. Case managers were recruited through their consumers' participation in the study. Staff invited every eligible consumer to participate in the study (individuals without DSM axis I diagnoses and a history of substance abuse were excluded). One person declined enrollment because of privacy concerns. All other participants gave informed consent to be interviewed and to have their program case managers interviewed—all of whom consented. Case managers who participated were paid $30 per interview, and all study protocols were approved by the New York University Institutional Review Board. The study period was from September 2005 to May 2008.

All cases in which a consumer study participant disengaged from services (N=35) were considered for inclusion in the analyses. Consumers were recruited when they entered a program and were followed for a year. Disengagement was defined as occurring when the study participant left the program during the course of the year. For housing-first consumers, disengagement entailed leaving their apartment and rejecting the program's case management services. For those in traditional settings, disengagement entailed rejecting the program's services and leaving before obtaining a referral to another program. These departures were considered to be contrary to program expectations and were often referred to by program staff as consumers "going AWOL." Of the 35 cases, six were excluded because disengagement occurred late in the study after the case manager interviews were completed. The postdeparture residential status was defined as the consumer's residential status during the 90-day period after leaving the program.

Data collection procedures

Case manager interviews of 30–45 minutes were conducted after the clients had left the program. Twenty-two (76%) of the interviews were conducted within one month of the disengagement, and 26 (90%) were conducted within two months. In only 11 of 29 cases (38%) did the same case manager complete the baseline and postdisengagement interview, which was a reflection of staff turnover. Interviews were conducted by four trained interviewers who were familiar with the mental health service system. Case manager interviews were open ended with questions asking for a description and reflection of their most recent interactions with the consumer and their assessment of the consumer's prognosis. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Consumers were retained in the study regardless of their status or program enrollment. Consumer residential status was tracked over the course of one year. For purposes of this study, the immediate circumstances for the 90 days following the consumer's disengagement were recorded from three monthly consumer tracking interviews that lasted ten to 15 minutes and inquired about their current life situation. One consumer declined to participate in follow-up after disengaging from services. Agency clinical records were used to obtain information on consumer demographic characteristics, tenure in the program, and diagnoses.

Data analysis

Individual case summaries of disengagement based on case manager interviews and consumer tracking interviews were developed to give an account of the disengagement episode. By using case manager interviews, within- and across-case analyses were conducted to develop themes related to the case manager's understanding of the disengagement, whether the case manager had anticipated the consumer's behavior, and the case manager's openness to working with the consumer in the future. In the 11 cases where this was possible, these accounts were compared with the same case manager's baseline assessment of the consumer's prognosis. Descriptive data matrices ( 30 ) were developed to aid the organization and conceptualize the findings. The first two authors compared independently derived findings in order to reach full consensus and to increase methodological rigor ( 31 ).

Results

Participant characteristics

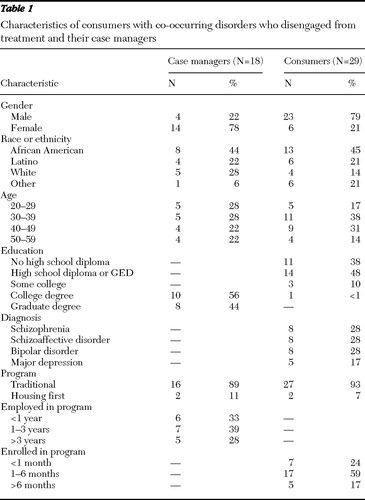

Case manager and consumer characteristics are described in Table 1 . Eleven case managers had one consumer in the study, four case managers had two consumers, two case managers had three consumers, and one case manager had four consumers. The majority of the 29 consumers were male and African American, a reflection of the demographic profile of people experiencing homelessness in New York City. Twenty-seven (93%) of the consumers who disengaged were in traditional programs ( Table 1 ). [A table showing more detail about each case of disengagement is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

|

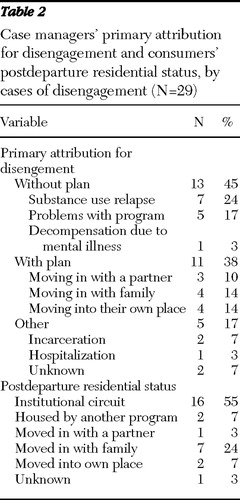

Table 2 shows case managers' primary attribution for disengagement and the postresidential status of the consumers. Case managers distinguished between consumers who notified them of their intent to leave and had a plan and those who left without warning and without an articulated plan. More than half of the consumers did not find stable housing after leaving their program.

|

Case manager perspectives on disengagement

Disengagement as part of the trade. The following themes emerged from the case manager interviews. Most case managers expressed having anticipated that their clients would leave the program prematurely, citing previous experience. As one case manager noted, "These kinds of places are inherently revolving doors." Another explained, "We're not taking bets, but sometimes me and the case managers, we'll get together and the clients will come in, and we can look and say, you know what, the client ain't going to make it. You could just tell sometimes by the way they come in, their behavior. And a lot of times we hope to be wrong." Some of the case managers spoke in schematic terms, such as "He's the kind of guy [who would disengage] and we knew it from the beginning" or "That type of person can't stay put too long." There was often a sense of inevitability and resignation to the possibility of disengagement, with one case manager concluding, "It's part of the trade."

In the baseline interviews, anticipating disengagement was not reported, but case managers clearly were concerned about the consumer's prospects in the program. One explained, "We don't have the highest expectations other than that they continue to show up. And [that they] know that we care about them." Referring to the program and its rules requiring sobriety, another case manager said, "It's hard to say right now.… If he doesn't stop smoking marijuana, I think he's gonna have a problem with that." In this case, the consumer was discharged to a more structured drug treatment setting. Some case managers expressed a belief that they could influence consumers to change their behaviors, with one explaining, "I told her too, you know, 'You really have to focus on yourself. You can't help your children if you're constantly getting high. Or you don't have a place to stay.' So I think that kind of woke her up too." Often consumers did disengage as a result of substance use, but one consumer, who was perceived by his case manager to be using substances, had actually negotiated a placement in independent living with another agency without the case manager's assistance or knowledge.

Disengagement as poor decision making. Virtually all case managers characterized disengagement as a mistake emanating from poor decision making on the part of the consumer. This held true even when consumers articulated a plan to leave and subsequently moved in with family members or on their own. Although one case manager conceded "at least he had a plan," most believed that consumers were not ready to make it on their own, attributing this to struggles with substance use. For instance, one case manager said, "He wants to use … and until he is committed to living his life sober, we can't help." This was often described in schematic terms, such as a consumer's being "nowhere near recovery yet. I think she's a chronic relapser." Another expressed frustration by saying, "He doesn't understand that there is a pattern, and we try to point it out."

Sometimes case managers attributed disengagement to the consumer's personality and difficult behaviors. One said, "I knew he would be challenging. He was very friendly, but at the same time he had a very strong sense of self-entitlement.… It just made it a very difficult combination to actually move forward with." Some viewed disengagement as an act of "self-sabotage," a phrase used to describe self-destructive behavior often precipitated by an impending referral to a less restrictive program. As one case manager stated, "He felt that he didn't have to listen to what staff had to say at that point, so we knew that when he was going through all of that, this is his signs that he's going to be sabotaging soon. So we saw those as signs of sabotaging, and that's what he did basically." This consumer did end up living on the streets.

Vocalizing disagreement with a consumer's decision was not uncommon. As one case manager recalled, "I didn't think it was a good decision at all. And I told him that." The consumer in this case returned to living with his mother after having complained that he was sexually molested at his program. Another case manager talked about a consumer who left to move in with his girlfriend, stating, "I think it's really unfortunate that he left, especially knowing who he decided to live with." Another said, "I'll tell them that they'll be back here in two weeks looking for a bed because their friend kicked them out." These opinions could have been a type of persuasion or simply an honest assessment, but case managers clearly put responsibility on the client.

The perception that disengagement was a mistake was often accompanied with a sense of disappointment, especially if the consumer was considered to show potential to do well. Consumers who were labeled "insightful," "very nice," or "the ideal consumer" were the ones in which case managers were more likely to say, "I'm disappointed because here's someone, in my assessment, [who] could have done so well" but instead was deemed to be "a big disappointment." Interestingly, only one case manager mentioned the program as contributing to disengagement by saying, "I can't blame them for leaving if they're not getting housing quick enough."

Coping with the revolving-door syndrome. Even when faced with a "disappointing" consumer, when asked whether they would be willing to work with the consumer again, most case managers answered affirmatively. One case manager said, "I would love for her to come back. She is an incredible person." Another said, "He's a little star," and added, "Hopefully, he'll reach out." In some cases, case managers said they would enforce a stricter regimen in order to better address substance abuse. In the few instances in which case managers were not willing to work with a consumer again, the decision was rooted in a belief that the consumer left them no alternative, which they expressed as, "[He] forced us to discharge him," "I think that he really sealed his fate," and "Basically, people are just tired of working with him."

Discussion

Most case managers spoke about disengagement as an inevitable part of their work. In retrospect, many reported having anticipated disengagement, with some employing schematic thinking by concluding this was the "type" of consumer who would disengage from services. In the cases where they had expected consumers to do well in the program, case managers expressed more disappointment. Although they did not frame their feelings in terms of personal rejection, they had clearly vested themselves in the consumer's success in the program. Given this dynamic, it is understandable that case managers might anticipate disengagement as a protective measure. Yet baseline interviews revealed that any concerns were balanced by a belief that their efforts would keep the consumer engaged.

A question arises about how the reality of frequent disengagement impinges on case managers' ability to remain optimistic, especially when they witness behaviors that they see as harbingers of future disengagement. It appears, on the whole, that case managers try to remain positive, support their consumers, and "hope to be wrong." Partly because case managers viewed disengagement as a common occurrence, many took a long-term view, expressing an openness to working with consumers if they returned to services. Their willingness to heal ruptured relationships demonstrated their adaptation to the revolving-door syndrome.

Disengagement was nearly always judged to be negative. Case managers clearly saw departure from services, even for those who left with a plan for their housing, as a mistake for the consumers. And in many cases, consumers did return to an institutional circuit of shelters, hospitals, and street homelessness. Given that the recovery movement has stressed the importance of letting consumers take risks and tolerating the possibility of failure, this raises the difficult issue of whether case managers should support consumer choice, even when that choice encompasses leaving services.

Maybe more problematic in a recovery era is the extent to which case managers placed the responsibility for disengagement on the consumer. Although they acknowledged that consumers were not satisfied with the treatment setting or there was a lack of program fit, they rarely reflected on the role of their program in the disengagement. This response seems counter to the increasing realization that the onus of disengagement is on the mental health system, which has failed to reach many people with severe mental illnesses ( 32 ).

Given that there were only two housing-first consumers who disengaged to compare with 27 consumers in traditional programs who did so, no meaningful group comparisons can be made. Some case managers were overrepresented in the sample because they were interviewed about multiple consumer departures. However, differences were found across cases of disengagement where consumers shared the same case manager, indicating variation at the consumer level. Finally, discussing disengagement retrospectively may have led to social desirability in the responses of some case managers.

Conclusions

The study highlights the tensions between the rhetoric of recovery, which stresses hope and optimism, and the reality that case managers face on a daily basis—consumers disengaging and often returning to the institutional circuit. However, despite this reality, case managers work hard to maintain relationships and retain a positive outlook for their consumers. The fact that most case managers claimed that they anticipated a consumer's disengagement indicates there may be the opportunity to provide case managers with interventions specifically designed to retain consumers in services during this critical time. However, when faced with a consumer who is planning to disengage, a recovery-oriented approach may suggest that case managers view their consumers' lives more holistically and strive to support these decisions rather than present their services as "all or nothing." At an organizational and policy level, programs need to consider their role in disengagement and provide more flexible recovery-oriented services that will ensure that consumers stay in services and benefit from them.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grants R01 69865 and F31 MH083372-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Blackwell B: From compliance to alliance: a quarter century of research, in Treatment Compliance and the Therapuetic Alliance. Edited by Blackwell B. Amsterdam, Harwood Academic, 1997Google Scholar

2. Brunette M, Mueser KT, Drake RE: A review of research on residential programs for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance abuse disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review 23:471–481, 2004Google Scholar

3. Calsyn R, Klinkenberg W, Morse G, et al: Recruitment, engagement, and retention of people living with HIV and co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders. AIDS Care 16:S56–S70, 2004Google Scholar

4. Jenkins J, Carpenter-Song E: The new paradigm of recovery from schizophrenia: cultural conundrums of improvement without cure. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 29:379–413, 2005Google Scholar

5. Laudet AB, Magura S, Cleland C, et al: Predictors of retention in dual-focus self-help groups. Community Mental Health Journal 39:281–297, 2003Google Scholar

6. Watkins KE, Shaner A, Sullivan G: The role of gender in engaging the dually diagnosed in treatment. Community Mental Health Journal 35:115–126, 1999Google Scholar

7. Rowe M, Fisk D, Frey J, et al: Engaging persons with substance use disorders: lessons from homeless outreach. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 29:263–272, 2002Google Scholar

8. Hopper K, Jost J, Hay T, et al: Homelessness, severe mental illness, and the institutional circuit. Psychiatric Services 48:659–665, 1997Google Scholar

9. Saylers MP, Tsemberis S: ACT and recovery: integrating evidence-based practice and recovery orientation on assertive community teams. Community Mental Health Journal 43:619–641, 2007Google Scholar

10. National Consensus Statement on Mental Health Recovery. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004Google Scholar

11. Mueser KT, Noordsy DL, Drake RE, et al: Integrated Treatment for Dual Disorders. New York, Guilford, 2003Google Scholar

12. Priebe S, Watts J, Chase M, et al: Processes of disengagement and engagement in assertive outreach patients: qualitative study. British Journal of Psychiatry 187:438–443, 2005Google Scholar

13. Aguilar-Gaxiola SA, Zelezny L, Garcia B, et al: Mental health care for Latinos: translating research into action: reducing disparities in mental health care for Mexican Americans. Psychiatric Services 53:1563–1568, 2002Google Scholar

14. Alverson HS, Drake RE, Carpenter-Song EA, et al: Ethnocultural variations in mental illness discourse: some implications for building therapeutic alliances. Psychiatric Services 58:1541–1546, 2007Google Scholar

15. Padgett DK, Henwood B, Abrams C, et al: Engagement and retention in services among formerly homeless adults with co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse: voices from margins. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 31:226–233, 2008Google Scholar

16. Crane-Ross D, Roth D, Lauber BG: Consumer and case managers' perceptions of mental health and community support services needs. Community Mental Health Journal 36:161–178, 2000Google Scholar

17. Lang MA, Davidson L, Bailey P, et al: Clinicians' and clients' perspectives on the impact of assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services 50:1331–1340, 1999Google Scholar

18. Klinkenberg WD, Calsyn RJ, Morse GA: The case manager's view of the helping alliance. Care Management Journals 3:120–125, 2002Google Scholar

19. Tunner TP, Salzer MS: Consumer perspectives on quality of care in the treatment of schizophrenia. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 33:674–681, 2006Google Scholar

20. Koekkoek B, van Meijei B, Hutschemaekers G: "Difficult patients" in mental health care: a review. Psychiatric Services 57:795–802, 2006Google Scholar

21. Rowe M: Crossing the Border: Encounters Between Homeless People and Outreach Workers. Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1999Google Scholar

22. Breeze JA, Repper J: Struggling for control: the case experiences of "difficult" patients in mental health services. Journal of Advanced Nursing 28:1301–1311, 1998Google Scholar

23. Bowditch J, Buono A: A Primer on Organizational Behavior. New York, Wiley, 2001Google Scholar

24. Mendias C, Kehoe J: Engagement of policing ideals and their relationship to the exercise of discretionary powers. Criminal Justice and Behavior 33:70–92, 2006Google Scholar

25. Fiske S, Kinder D, Larter W: The novice and the expert: knowledge-based strategies in political cognition. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 19:381–400, 1983Google Scholar

26. Lurigio A, Carroll J: Probation officers' schemata of offenders: content, development, and impact on treatment decisions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48:1112–1126, 1985Google Scholar

27. Colwell L: Cognitive heuristics in the context of legal decision making. American Journal of Forensic Psychology 23:17–41, 2005Google Scholar

28. Alexander JA, Lichenstein R, D'Aunno TA, et al: Determinants of mental health providers' expectations of patients' improvement. Psychiatric Services 48:671–677, 1997Google Scholar

29. Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF: Pathways to Housing: supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 51:487–493, 2000Google Scholar

30. Miles M, Huberman A: Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1994Google Scholar

31. Padgett D: Qualitative Methods in Social Work Research: Challenges and Rewards. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1998Google Scholar

32. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar