Factors Related to Knowledge Retention After Crisis Intervention Team Training for Police Officers

Criminalization of individuals with serious mental illnesses, including incarceration for minor, nonviolent infractions, is a widely recognized problem ( 1 ). Established in Memphis in 1988, the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) model is a specialized program that aims to advance safety during interactions between police officers and individuals with psychiatric illnesses, substitute enhanced access to psychiatric services in lieu of unnecessary incarceration, and promote partnerships between local law enforcement and mental health services ( 2 ). This collaborative model, also known as the Memphis model, has become a prototype for numerous municipalities. Despite the growing pace at which CIT programs are being implemented nationwide, there remains relatively little research on the CIT model ( 3 ). Research has not yet examined retention of knowledge among CIT-trained officers, despite potentially crucial implications of such research in terms of enhancing the training component of the CIT model.

CIT training is not designed to be ongoing, and the need for continuing education has not been sufficiently considered. In this study it was expected that CIT officers' test scores on mental health knowledge, which would be higher immediately after CIT training, would decline over time after completion of training. Therefore, we hypothesized that knowledge retention would be higher among officers for whom less time had elapsed since training. Additionally, a number of other variables were examined as potential predictors of retention of mental health knowledge.

Methods

Implementation of CIT in Georgia is based on a multidisciplinary collaboration among numerous organizations—for example, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, the Georgia Department of Human Resources, and the Georgia affiliate of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. The CIT curriculum is approved by Georgia Peace Officer Standards and Training to ensure quality and consistency of training in localities throughout the state. The 40-hour course is composed of lectures on psychiatric disorders and related topics, visits to local emergency facilities and inpatient psychiatric units, and performance-based deescalation training. Each class accommodates 15 to 25 officers. The CIT designation is awarded to police officers who complete the course and pass the 40-item knowledge test administered at the end of the training week. Since late 2004, approximately 2,100 officers from about 50 of Georgia's 159 counties have been trained.

This study relied on the 40-item, paper-and-pencil, multiple-choice knowledge test administered at the conclusion of CIT training. An electronic version of this knowledge test was combined with a survey of sociodemographic characteristics for an online follow-up survey. Because the 40-item exam had undergone several revisions, only 17 items remained unchanged, and these items—identical on the posttraining test and the follow-up test—were used in this analysis. Thus possible scores ranged from 0 to 17, with higher scores indicating greater knowledge. Three items dealt with depression, two with psychosis, two with trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder, two with personality disorders, three with other mental illnesses, and five with miscellaneous issues—for example, responding to crisis situations and barriers to treatment. An online survey tool was used to distribute surveys to officers. Posttraining knowledge tests of officers completing the online survey were made available by the Georgia Public Safety Training Center.

E-mails about the study were sent to 1,198 officers, and at the close of the one-month online survey (May 2007), 203 responses were received. Among the officers completing the survey, the research team was able to match 88 (43%) follow-up tests with posttraining paper-and-pencil tests. The remainder of the online follow-up surveys could not be matched because of lack of identifying information on some posttraining tests, which were administered to ensure completion of the training and basic competency, rather than for research purposes.

The study was approved by the university's institutional review board, and all participants provided informed consent before completing the online follow-up survey. Bivariate statistical tests were conducted with SPSS version 14.0 and included paired-samples Student's t tests, independent-samples t tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, and Spearman correlations.

Results

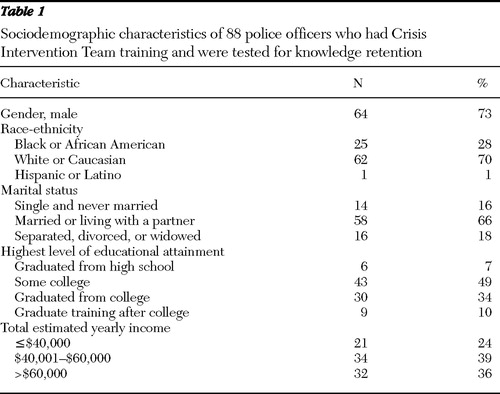

The mean age of the 88 officers was 42.4±9.0 years (range 24 to 63 years), and participants had worked as a police officer for an average of 14.7±8.7 years (range two to 35 years). As shown in Table 1 , nearly three-fourths of officers were male, most self-identified as white or Caucasian, and most were married or living with a partner. Nearly all officers had completed some college or had graduated from college, and three-fourths earned more than $40,000 annually.

|

A majority of officers (65 officers, or 74%) reported having volunteered for CIT training, whereas 23 (26%) reported that they were assigned to the training. Over three-fourths of officers (70 officers, or 80%) reported having had no additional mental health training, although 17 (19%) had received some additional training. Officers lived and worked in approximately 40 counties, both urban and rural.

Immediately after CIT training, the 88 officers had a mean test score of 16.7±.8 (range 12 to 17). At the time of the follow-up assessment, the mean score was 14.7±1.9 (range 8 to 17) (t=9.69, df=81, p<.001). Only five officers showed improvement in scores (two improved by 2 points, and three improved by 1 point). The mean difference from the posttraining test administration to the follow-up assessment (computed by subtracting the follow-up score from the posttraining score) was 2.0±1.8 (range -2 to 7). Officers completed the follow-up knowledge test an average of 46.1±34.4 weeks (range 0 to 117 weeks) after CIT training. Five officers who had taken the follow-up test less than one month after having completed CIT training were excluded from further analyses.

Seven potential predictors of mental health knowledge retention were examined: age, gender, level of educational attainment, years of police service, voluntary versus assigned to CIT training, past additional mental health training, and weeks from completing CIT training to the follow-up assessment. Of these, only one was a significant predictor—years of police service was inversely correlated with the difference between posttraining and follow-up knowledge test scores ( ρ =-.34, p=.005). When this variable was dichotomized based on a mean or median split, officers who had served two to 14 years had significantly greater declines in test performance (2.4±1.7) than those who had served 15 to 35 years (1.6±1.8) (z=2.27, p=.02). Knowledge scores immediately after CIT training were not correlated with years of service ( ρ =.02, p=.89), but follow-up scores were ( ρ =.35, p=.004). When the dichotomized variable was used, officers with less than 15 years of service had the same posttraining scores as those with 15 or more years of service (mean scores 16.6±1.0 and 16.7±.7, respectively), but the less experienced officers had lower follow-up scores (mean score 14.3±1.9) than the more experienced officers (mean score 15.2±1.6) (t=2.17, df=74, p=.03).

Discussion

Two key findings emerged from this preliminary study of mental health knowledge retention among CIT officers. First, as expected, knowledge scores decreased in the months after CIT training. Second, years of service as a police officer significantly predicted retention of knowledge, whereas other variables, such as age, educational attainment, and time since completion of CIT training, did not.

The decline in knowledge scores, although not particularly surprising, may have programmatic implications for this very rapidly expanding collaborative model that has spread to hundreds of communities across the United States ( 4 ). It suggests that CIT programs should consider providing officers with continuing education about mental illnesses and related topics—for example, treatment services and deescalation interventions. Continuing education is important for specialized professions, including firefighters, emergency medical attendants, and physicians ( 5 , 6 , 7 ), and Addy and James ( 8 ) emphasized the need for in-service training or continuing education training opportunities at the first National CIT Conference. Our study is the first to provide preliminary empirical evidence that continuing education deserves consideration as an enhancement of the CIT program.

Although the decline in knowledge scores was statistically significant, further research is needed to determine the practical meaningfulness of the differences in posttraining and follow-up knowledge scores. It is not known whether the decline in knowledge noted is insignificant because it was a small percentage of the overall number of items or whether the decline was very serious because the test itself was quite easy to start with. A more refined measurement instrument is required to determine whether these changes in knowledge are associated with real-life behavioral outcomes of officers—for example, referral decisions and deescalation skills. How much information is needed to be an effective CIT officer has yet to be determined, and standardized competencies have not been defined.

Surprisingly, a shorter duration between CIT training and the follow-up survey was not a predictor of knowledge retention but years of service as a police officer emerged as a significant determinant. Previous studies suggest that officers differ on several characteristics based on years of service—for example, the relationship between education and proficiency in report writing is moderated by years of police experience ( 9 ). The interactions between background variables—for example, years of service as a police officer and past exposure to the mental health profession—may be important in understanding attitudinal changes, knowledge retention, and other key officer-level outcomes of CIT training. Thus the characteristics of officers before entry into CIT training may be a valuable area of research. It is possible that CIT officers with more experience retain knowledge better because they have had more mental health training or more encounters with persons with mental illnesses.

Several methodological limitations should be considered. First, the sample was relatively small and the response rate was low, although not uncommonly low ( 10 , 11 , 12 ). Second, participating officers may have been different from nonrespondents in meaningful ways, and selection bias cannot be excluded, because responders may be more diligent and thus more likely to retain the content of their training or because they may be more enthusiastic about or committed to CIT. Third, findings may have been influenced by a ceiling effect. Only five officers evidenced slight improvements in scores. Given that the test appeared to be "too easy," the variability in changes in scores was very restricted. Furthermore, implicit in the analysis is that each item of the test received equal weight, although this might not be appropriate if, for example, officers are more likely to remember concepts that are more useful. To address these concerns, future research should use a knowledge test developed through careful item analysis.

Conclusions

The deinstitutionalization of individuals with mental illnesses and the shift toward community-based treatments means that responding to individuals with mental illnesses will remain a challenging aspect of police work ( 13 ). The CIT program has become an exemplary program that directs persons with mental illnesses to psychiatric services rather than jail when possible. The findings presented here indicate that CIT officers would benefit from continuing education about mental illnesses and that more seasoned officers may be better candidates for CIT training, at least in terms of knowledge retention.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported with funds from a grant from the Georgia Department of Human Resources Division of Family and Children Services to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. The authors greatly appreciate assistance provided by Nora Lott Haynes, Ed.S., Harriett Laurence, B.S., Janet R. Oliva, Ph.D., and April Wrenn, B.S.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Lamb RH, Weinberger LE: Persons with severe mental illnesses in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483–492, 1998Google Scholar

2. Dupont R, Cochran S: Police response to mental health emergencies—barriers to change. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 28:338–344, 2000Google Scholar

3. Compton MT, Bahora M, Watson AC, et al: A comprehensive review of extant research on Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) programs. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 36:47–55, 2008Google Scholar

4. Law Enforcement/Mental Health Partnership Program. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance. Available at www.ojp.usdoj.gov/BJA/grant/LEMHPartnership.pdfGoogle Scholar

5. Clark BA: Higher education and fire service professionalism. Fire Chief, Sept 1993, pp 50–53Google Scholar

6. Latman NS, Wooley K: Knowledge and skill retention of emergency care attendants, EMT-As, and EMT-Ps. Annals of Emergency Medicine 9:183–189, 1980Google Scholar

7. Roter D, Rosenbaum J, de Negri B, et al: The effects of a continuing medical education programme in interpersonal communication skills on doctor practice and patient satisfaction in Trinidad and Tobago. Medical Education 32:181–189, 1998Google Scholar

8. Addy C, James RK: Panning for gold: finding the best CIT practices across the country. Presented at First National CIT Conference, Columbus, Ohio, May 11–12, 2005Google Scholar

9. Michals JE, Higgins JM: Relationship between education level and performance ratings of campus police officers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 12:15–18, 1997Google Scholar

10. Tse ACB: Comparing the response rate, response speed and response quality of two methods of sending questionnaires: email vs mail. Journal of the Market Research Society 40:353–361, 1995Google Scholar

11. Basi RK: World Wide Web response rates to socio-demographic items. Journal of the Market Research Society 41:397–441, 1999Google Scholar

12. Kent R, Lee M: Using the Internet for market research: a study of private trading on the Internet. Journal of the Market Research Society 41:277–285, 1999Google Scholar

13. Wells W, Schafer JA: Officer perceptions of police responses to persons with a mental illness. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 29:578–601, 2006Google Scholar