A Multisite Study of Implementing Supported Employment in the Netherlands

Employment is central to modern human existence. A paid job provides an income, a valued social position, and a personal identity, and by promoting opportunities for skill development and social contacts, it is also positively related to mental health ( 1 ). Many people with severe mental illnesses identify employment as crucial to their recovery process ( 2 ). Obtaining and maintaining competitive employment, however, continues to be a major challenge. A report of the World Health Organization and the International Labor Organization ( 3 ) estimates a global unemployment rate of 90% among persons with severe mental illnesses. Nevertheless, most of these individuals have a desire to work, and they nearly always prefer competitive employment over sheltered work ( 4 , 5 , 6 ).

In the Netherlands, a small western European country with 16 million inhabitants, persons with severe mental illnesses consistently have the worst employment outcomes of all disability groups; only 12% are enrolled in competitive jobs ( 7 ). The Dutch approach to vocational rehabilitation for this group has been a cautious one, mainly encompassing prevocational training, sheltered employment, volunteer work, or trainee placements in regular businesses ( 8 ). Many clinicians in the Netherlands believe that competitive employment is too ambitious or too stressful for clients with severe mental illnesses. Clients are offered work tasks in segregated settings to prepare them for competitive employment, but the progression from sheltered to competitive jobs is not substantial ( 9 ). Another feature of Dutch practice is the parallel organization of mental health services and vocational services, based on the belief that this segregation enables employment specialists to focus solely on vocational issues without causing any stigma. Although some services do focus on competitive employment, their results are mostly modest. A major difficulty of these services is the lack of collaboration between care providers and employment specialists ( 10 ).

Other vocational services—that is, generic vocational agencies that work on a profit basis with unemployed people in general—are difficult to access by persons with severe mental illnesses. The main reason for this is that these services provide limited supervision and relatively brief, time-limited reintegration pathways, whereas persons with severe mental illnesses often need intensive and long-term supervision and guidance ( 7 ).

The individual placement and support model, which represents a standardization of supported employment for persons with severe mental illnesses ( 11 , 12 ), compensates for most of the shortcomings of conventional vocational programs ( 13 ). Individual placement and support focuses on several key features: securing competitive employment of at least minimum wage, rapid job search, prioritizing the consumer's preferences, providing long-term support, and integrating supported employment with mental health services. This integrated approach makes it easier to reach consumers and improves coordination between vocational services and other services ( 13 ).

On the basis of several systematic reviews and meta-analyses, supported employment is considered an evidence-based practice ( 12 , 14 , 15 ). Stimulated by the positive outcomes in the United States, practitioners in Europe have become interested in adopting the individual placement and support model. Whether this model will also be successful for clients in Europe remains an open question. The first randomized controlled trial of supported employment in Europe, a study in six countries (England, Bulgaria, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland), has recently been completed ( 16 ).

In Europe, especially for jobs that pay at the lower end of the labor market, the unemployment rates are high. Also, the "benefit trap" (financial disincentives to return to work) seems to be an impediment to successful vocational rehabilitation in some European countries. Therefore, socioeconomic conditions and the individual placement and support model itself may need to be modified for the European context. For this reason, we conducted a multisite implementation study to determine the feasibility of supported employment in the Dutch context and to identify obstacles that may need to be overcome.

The Dutch implementation study reported here has been closely linked with the research program in the United States called the National Impementing Evidence-Based Practices Project ( 17 , 18 , 19 ). The U.S. demonstration program addresses the implementation of five evidence-based practices in 53 routine mental health settings across eight states.

The main objective of the Dutch study was to determine whether the individual placement and support model of supported employment could be implemented in the Netherlands. We sought to answer the following questions: what is the level of fidelity of the implementation, what are the employment outcomes in the four sites (client outcomes and job characteristics), what are the barriers to implementation, and what strategies to overcome these barriers are successful?

Methods

To the greatest extent possible, all methods replicated those used in the U.S. National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project ( 20 ).

Setting

In 2003 four Dutch mental health agencies began to implement individual placement and support programs of supported employment. Employment specialists from vocational services (such as generic vocational agencies, sheltered workshops, and rehabilitation centers) were assigned to mental health teams delivering comprehensive treatment and care for persons with severe mental illnesses. The employment specialists were to assist people in getting jobs, offer follow-along supports after job placement, and spend most of their time in the community. They maintained close contact with the mental health clinicians and regularly attended team meetings. Clients were informed about the program by letter and leaflet, by their clinician, or during an information meeting. They could be self-referred or referred by their clinician. All clients who were 18 years and older and expressed interest in competitive employment were eligible.

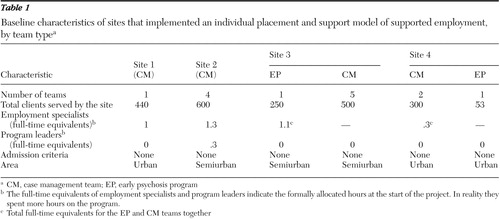

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sites. Sites were selected on criteria including a case manager-client ratio of at most 1:30, a client population of at least 240, regular contacts with vocational services, and willingness to provide funding.

|

Training and consultation

The sites followed a Dutch translation of the supported employment implementation resource kit (or toolkit), developed in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project ( 21 ). The toolkit consists of a user's guide, a manual for employment specialists, two videotapes, information for all stakeholders, client outcome measures, a fidelity scale, and PowerPoint presentations.

Employment specialists participated in nine training sessions that included the following subjects: barriers to implementation, communication skills, assessment, job finding, follow-along supports, Social Security system, employment integration policy, and integration in mental health teams. An expert trainer provided the sessions and consultation to program leaders on site-specific implementation barriers. Leaders of the four programs exchanged information on their experiences regularly.

The Dutch sites also were supported by training sessions from American experts. In addition, Ms. Becker, one of the originators of individual placement and support and the leading expert in assessment of its fidelity, participated in telephone conferences to discuss implementation problems. Finally, a Dutch delegation of supported employment practitioners visited successful programs in the United States.

Measures

Data were collected from April 2003 to April 2005. Program-level fidelity was assessed at zero, 12, and 24 months with the 15-item Individual Placement and Support Fidelity Scale ( 22 ). This scale consists of three sections: staffing (three items), organization (three items) and services (nine items). Possible scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating closer adherence to the model. Higher-fidelity programs attained high scores (4.0 or higher) on most items, whereas lower-fidelity programs had some major problems on specific items.

The assessments were based on multiple interviews (with program leaders, employment specialists, clients, and family members), direct observation of team meetings, and agency records.

Researchers monitored the implementation process at zero, 12, and 24 months using semistructured interview schedules developed for the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices project. Data on barriers to and facilitators of implementation and data on strategies used to overcome barriers were collected through direct observation, examination of records, and interviews with program leaders, clinical leaders, managers, and the trainer.

Employment specialists collected client-level information using a structured form containing three sections: intake (data on client characteristics), services (data on services by employment specialists), and job (data on competitive jobs).

Data on employment outcomes of the four sites were collected by the program leaders (100% response). A form with clearly defined outcomes (regular paid job, paid job in a sheltered setting, volunteer job in a community setting) was administered.

Data analysis

Two researchers independently coded the same transcripts of the interviews and additional data by using the qualitative data analysis computer program winMAX (version 97) ( 23 ). A comprehensive coding framework was developed that comprised categories representing main program and practice areas. To ensure consistency and reliability in results, the two researchers cross-checked each other's results. A high degree of agreement was found between the two researchers in terms of fidelity ratings and identifying barriers to and facilitators of implementation. Discrepancies in fidelity ratings were discussed by the researchers to arrive at consensus.

The study was judged exempt from review by an institutional review board and did not require informed consent.

Results

Program fidelity

Fidelity ratings for the four sites were assessed at zero, 12, and 24 months. At the baseline assessment, the mean fidelity rating of 1.8±.5 (range 1.1–2.2) indicates that the implementation of supported employment was in a nascent stage. At 12 months, the mean±SD fidelity score increased to 3.8±.2 (range 3.5–4.0). At 24 months, the mean score was 4.1±.3, and differences among the four sites became apparent. Sites 2 and 3 attained a score of 4.3 (referred to as higher-fidelity programs), and sites 1 and 4 reached scores of 4.0 and 3.6 (referred to as lower-fidelity programs).

All four sites reached only moderate scores on two fidelity items, namely finding permanent jobs and providing services in the community. This finding implies that job finding and follow-along support should be provided in community settings. However, instead of building relationships with employers in face-to-face contacts, employment specialists mainly used telephone, e-mail, and Internet to do so.

Client outcomes

Table 2 shows characteristics of the 233 clients (74% of sample) for whom a monitoring form was completed (of a total of 316 who received supported employment services). The study group was predominantly male, the mean age was 35±10, and most clients were living independently. At intake 107 participants (46%) did not perform any vocational activities. The most common diagnoses were schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. On average, participants had received 8±7 years of mental health services.

|

The population of sites 2 and 3 included fewer clients with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders and more clients with vocational activities at baseline than the population at site 4. Chi square tests were run for three of the four sites (site 1 was excluded because of the small sample). Differences between sites were significant on primary diagnosis ( χ2 =13.2, df=2, p=.001) and vocational status ( χ2 =22,4, df=4, p<.001).

More than one-third of all participants (122 participants, or 39%) dropped out of the supported employment programs. Some clients left the program prematurely because they changed their minds about seeking competitive jobs (preferring volunteer or sheltered jobs), some suffered relapses, and some were excluded from the program because of nonattendance.

Of the 316 total participants, 56 (18%) obtained competitive jobs. Sites 2 and 3 had the highest competitive employment rates (25% and 19%), whereas sites 1 and 4 achieved lower rates (14% and 16%). Differences in employment outcomes between the sites were not significant.

All competitive jobs (44 jobs total) were in a community setting, and clients earned at least minimum wage. Most jobs were entry level, such as cleaner, factory worker, warehouse worker, or caterer. Most of the jobs were temporary, although seven clients obtained a permanent position. Most jobs were part-time, with an average of 22±13 hours per week (range 1–40 hours). At the end of the research period, clients had worked 27±18 weeks on average. The main reasons for job terminations were ending of contracts and quitting. Two clients were fired from their jobs.

Facilitators, barriers, and strategies

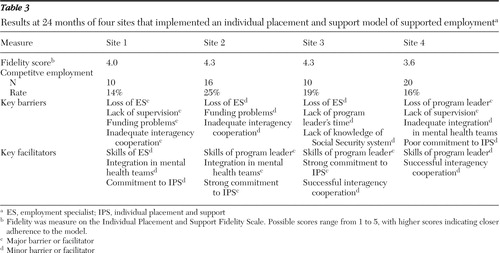

Table 3 shows the key barriers to and facilitators of the four sites. Implementations at all four sites were impeded by loss of employment specialists, program leaders, or both. In addition to temporary dropout because of illness, six employment specialists quit their jobs. They left the program for various reasons: some didn't like the job, others moved abroad or had to quit because their organization (a vocational agency) withdrew from the program. Two sites succeeded in overcoming these problems by quickly replacing staff.

|

Funding problems presented a critical barrier at three sites. Only one site was financed by the public mental health authority. At the other three sites, employment specialists had to apply for reintegration benefits for their clients through the local government or the Social Security agency. These application procedures were often complicated and time consuming.

Another barrier was the lack of time for program leaders to manage the supported employment program. Only one program leader was formally allocated time (12 hours per week) for the program. The other three had to direct the program while performing their regular duties.

Inadequate cooperation between the mental health organizations and vocational services, especially the profit-based vocational agencies, proved to be a challenge. The approaches of these services often interfered with the principles of supported employment.

Cultural values, disability policies, and the labor market were ubiquitous barriers. The Dutch Social Security system is built upon the "solidarity principle," which means that all people in the community will be cared for. For employers in the Netherlands, hiring an individual with a disability presents a major risk. Once a person is hired, an employer can have a difficult time attempting to fire this employee ( 24 ). People with disabilities who are dependent on Social Security benefits risk the "benefit trap" and may be faced with financial disincentives to return to work. Also, the Dutch labor market offers few opportunities at the lower end of the labor market: there is high unemployment among low-skilled workers.

The most important facilitators of the implementation process were strong personal commitments by program leaders and the skills of the vocational team members. Without time allocations, program leaders were required to manage the new programs, provide supervision, and also arrange financing for the program. Those who succeeded were highly valued because of their dedication and enthusiasm.

Successful integration of employment specialists in the mental health teams was an important facilitator at two of the four sites. Success was mainly attributable to the teams' attitudes toward supported employment. Specific strategies to stimulate integration included assigning case managers with special responsibilities for supported employment, physical colocation of the employment specialists with mental health teams, and regular team meeting discussion of clients' employment opportunities.

Finally, local leadership teams played an important role at two of the four sites. These teams were often helpful in making changes to policy, financing, and organizational structure.

Discussion

The application of qualitative and quantitative methods and the use of multiple sources of information provide confidence in the accuracy of the findings. By comparing two higher-fidelity programs with two lower-fidelity programs, we identified several factors that affected the implementation process in a positive or negative way. However, the relative weight of these factors remains unknown.

Several findings from our study warrant emphasis. First, the Dutch sites in our study reached lower levels of fidelity than the U.S. sites in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project ( 20 ). At 24 months, the mean fidelity score of the Dutch sites was 4.1, compared with 4.4 of the supported employment sites of the U.S. project ( 20 ). However, the mean baseline fidelity score of the U.S. sites (2.8) was also higher than that of the Dutch sites (1.8), which implies that the rate of change in fidelity during the two years was higher in the Netherlands.

Second, we identified numerous barriers to implementing supported employment within the Dutch system. Supported employment represents a new service approach that requires new attitudes and expectations regarding clients' recovery, a new organizational structure, extensive training, and new mechanisms of financing. It may also necessitate changes in employment and disability laws, which currently serve as barriers to reintegrating people with disabilities into the workforce. A new service like individual placement and support certainly needs tailoring and contextual study for successful transfer to a different culture.

Third, several factors differentiated higher-fidelity programs from lower-fidelity programs. Higher-fidelity programs had more facilitators and experienced fewer financial and organizational barriers than lower-fidelity programs, as is shown in Table 3 . Furthermore, the client population of the higher-fidelity programs included fewer clients with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders and more clients with vocational activities at baseline than the lower-fidelity programs. However we found no statistically significant association between fidelity and employment outcomes, unlike findings in previous U.S. studies ( 25 , 26 ). This finding could be attributed to the relatively small difference in fidelity between the sites, as well as to the small samples.

Fourth, the employment rates that we observed (14%–25%) were considerably lower than those reported in the U.S. studies ( 12 ). Lower employment rates could be a result of the characteristics of the Dutch system described above. Lower competitive employment outcomes of supported employment have also been found in Canada ( 27 ) and in other European countries ( 16 ). The availability of alternatives for regular paid work in the Netherlands (including social firms and sheltered work) could be a reason for a diminished attractiveness of competitive employment for clients and probably also accounts for their high dropout.

Moreover, our study sites had great difficulty acquiring permanent jobs, which is largely due to Dutch regulations. In the Netherlands, employees often start a new job with a half-year or one-year contract. After this first contract, two more temporary contracts can follow or the contract can be converted into a permanent job.

Compared with the U.S. labor market, the Dutch labor market allows for a small number of entry-level jobs that are more elastic and less vulnerable to economic downturns ( 11 ). These jobs, which are considered part of the secondary labor market ( 28 ), have historically been used to absorb young workers, unskilled and poorly educated workers, immigrants, and persons with disabilities. As described before, the Dutch Social Security system offers more security for people with disabilities than the U.S. Social Security system does. Consequently, in the Netherlands, these persons experience less financial incentive to work for wages.

This pilot study addressed implementation at only four sites—all early adopters—and occurred in the context of minimal organizational, training, and financing supports. Future attempts to implement and study the effectiveness of supported employment in the Netherlands will have to address many of the barriers identified here.

Conclusions

At 24 months, the four sites reached a fidelity score of 4.1, indicating that the individual placement and support model is indeed practicable in the Netherlands. However, our results suggest that the implementation of this model can succeed only under certain conditions. Solid project management will require changes in financing and organizational structures. At a community level, changes in cultural beliefs and attitudes are needed. At a policy level, changes in labor and disability regulations will be necessary.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by ZonMw and the mental health agencies Altrecht, GGZ Eindhoven, GGZ Groningen, UMCG, and Parnassia. The authors thank the staff at the four sites for supporting the intervention and evaluation activities of this project.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Rüesch P, Graf J, Meyer PC, et al: Occupation, social support and quality of life in persons with schizophrenic or affective disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 39:686–694, 2004Google Scholar

2. Provencher HL, Gregg R, Mead S, et al: The role of work in the recovery of persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 26:132–144, 2002Google Scholar

3. Harnois G, Gabriel P: Mental Health and Work: Impact, Issues and Good Practices. Geneva, World Health Organization, International Labour Organization, 2000Google Scholar

4. Bedell JR, Draving D, Parrish A, et al: A description and comparison of experiences of people with mental disorders in supported employment and prevocational training. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21:279–283, 1998Google Scholar

5. Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Mueser P: A prospective analysis of work in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:281–296, 2001Google Scholar

6. McQuilken M, Zahnisher JH, Novak J, et al: The work project survey: consumer's perspectives on work. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 18:59–68, 2003Google Scholar

7. Michon HWC: Personal Characteristics in Vocational Rehabilitation for People With Severe Mental Illnesses. Utrecht, Netherlands, Trimbos Institute, 2006Google Scholar

8. Gaal E, van Weeghel J, von Campen M, et al: The trainee-project: family-aided vocational rehabilitation of young people with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 26:101–105, 2002Google Scholar

9. Michon H, Ketelaars D, van Weeghel J, et al: Accessibility of government-run sheltered workshops to people with psychiatric histories. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:252–257, 1998Google Scholar

10. Drake RE, Becker DR, Bond GR, et al: A process analysis of integrated and non-integrated approaches to supported employment. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 18:51–58, 2003Google Scholar

11. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313–322, 2001Google Scholar

12. Bond GR: Supported employment: evidence for an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:4, 345–359, 2004Google Scholar

13. Becker DR, Drake RE: A Working Life for People With Severe Mental Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

14. Crowther R, Marshall M, Bond G, et al: Vocational rehabilitation for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2:CD003080, 2001Google Scholar

15. Cook JA, Leff HS, Blyler CR, et al: Results of a multisite randomized trial of supported employment interventions for individuals with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:505–512, 2005Google Scholar

16. Burns T, Catty J, Becker T, et al: Supported employment for people with severe mental illness: a European multi-centre controlled trial. Lancet, in pressGoogle Scholar

17. Drake RE, Goldman HS, Leff HS, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health settings. Psychiatric Services 52:179–182, 2001Google Scholar

18. Mueser KT, Torrey WC, Lynde D, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for people with severe mental illness. Behavior Modification 27:387–411, 2003Google Scholar

19. Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 52:45–50, 2001Google Scholar

20. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Whitley R, et al: Fidelity Outcomes in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project. Psychiatric Services 58:1279–1284, 2007Google Scholar

21. Becker DR, Bond GR, Mueser KT, et al (eds): Practitioners' and Clinical Supervisors' Workbook, in Supported Employment Implementation Resource Kit. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project, 2002Google Scholar

22. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: A fidelity scale for the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 40:265–284, 1997Google Scholar

23. Kuckartz U: WinMAX 97 Scientific Text Analysis for the Social Sciences: User's Guide. Berlin, BSS, Mar 1998Google Scholar

24. Korpel MHT: Supported employment behind the Netherlands' dikes: trends in vocational rehabilitation for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 6:97–105, 1996Google Scholar

25. Becker DR, Smith J, Tanzman B, et al: Fidelity of supported employment programs and employment outcomes. Psychiatric Services 52:834–836, 2001Google Scholar

26. Becker DR, Xie H, McHugo GJ, et al: What predicts supported employment outcomes? Community Mental Health Journal 42:303–313, 2006Google Scholar

27. Latimer EA, Lecomte T, Becker DR, et al: Generalisability of the individual placement and support model of supported employment: results of a Canadian randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 189:65–73, 2006Google Scholar

28. Catalano R, Drake RE, Becker DR, et al: Labor market conditions and employment of the mentally ill. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 2:51–54, 1999Google Scholar