Treatment of Cardiac Risk Factors Among Patients With Schizophrenia and Diabetes

Patients with schizophrenia have a life expectancy that is 20 percent shorter than that of the general population, with mean life spans of only 57 years for men and 65 years for women ( 1 ). Although higher rates of suicide and accidental death play a role, approximately two-thirds of the excess mortality in this population is due to comorbid medical illnesses ( 2 , 3 ). Of particular importance is the increased rate of cardiovascular mortality among patients with schizophrenia, which is approximately twice that seen in the general population ( 4 ). Several factors are thought to contribute to this elevated risk of heart disease, including a sedentary lifestyle, poor dietary habits, significant tobacco use, and elevated rates of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and type 2 diabetes ( 5 ). The latter three factors have received increasing attention, for it appears that the most commonly used treatments for schizophrenia, including clozapine and olanzapine, can exacerbate these problems ( 6 ). Because individual cardiac risk factors have an additive effect on heart disease risk, ameliorating even one of these factors will benefit patients' well-being ( 7 , 8 ).

Although recent practice guidelines have emphasized the role that psychiatrists can play in screening for cardiovascular risk factors, referral to a primary health care provider is the usual recommendation for any positive finding ( 5 , 6 , 9 , 10 ). This suggested practice fits well with current practice, given that 74 percent of psychiatrists reported that they refer "most or all" of their patients to another physician for medical care related to these cardiac risk factors ( 11 ). For most patients with schizophrenia, therefore, medical management of any identified risk factors will take place within the outpatient general medical setting.

Evaluating the quality of this medical care, particularly for patients with schizophrenia and identified cardiac risk factors such as diabetes, is therefore of critical importance to improving their overall health. Some evidence suggests that the level of care received by patients with severe mental illness (including schizophrenia) is suboptimal, including lower rates of cardiac catheterization and routine preventive care ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). The quality of diabetes-related care, specifically, also appears to be worse among the patients with mental illness, as demonstrated by three recent large-scale studies ( 15 , 16 , 17 ). Even when appropriate care is administered, patient-related factors, including lower medication adherence ( 18 ), gaps in diabetes-specific knowledge ( 19 ), and overall poorer self-care ( 20 ) may limit the effectiveness of care in this group.

To examine the appropriateness and effectiveness of the outpatient medical management of patients with schizophrenia, we compared the general medical care that they received with that received by their counterparts who had no mental illness. We focused specifically on the quality of care related to the major modifiable cardiac risk factors that is provided to patients already diagnosed as having diabetes, given the prevalence of diabetes among patients with schizophrenia, the importance of these factors in preventing cardiac disease, and the clear diabetes-related guidelines available to evaluate treatment appropriateness and effectiveness. We specifically hypothesized that outpatients with diabetes and schizophrenia (when compared with outpatients with diabetes and no severe mental illness) would be less likely to receive appropriate treatment for diabetes and associated cardiac risk factors, as defined by optimal evidence-based practice. We also hypothesized that outpatients with diabetes and schizophrenia would be less likely to receive effective treatment for diabetes and associated cardiac risk factors, as defined by quality-of-care benchmarks.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This cross-sectional study assessed the demographic characteristics, cardiac risk-factor profile, and quality of care provided to a cohort of outpatients with diabetes at five internal medicine practices in the greater Boston area. The study was approved by the Partners Health Care System Institutional Review Board. The methods used to generate this database have been described previously ( 21 ). Briefly, patients with diabetes seen between January 1, 2000, and July 31, 2003, were identified with the use of billing claims for nongestational diabetes ( ICD-9 codes 250.00-250.90), laboratory testing, medical record-based problem lists, and medications. Analyses were restricted to patients who had at least two outpatient visits, including one during the early period of observation (January 1, 2000, to August 31, 2001) and one during the later period of observation (December 1, 2001, to July 31, 2003), to capture a representative outpatient sample (and to exclude single-visit consultations). All comorbidity and treatment variables were based on the final available measure within the study period for each patient. For two of the clinics, patients were identified by manual chart review by trained research nurses. This information was then used to create an automated algorithm (diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 98 percent, compared with gold-standard chart review) to identify patients from the electronic medical record at the other three clinics.

Using this database, we identified 211 patients diagnosed, according to billing codes ( ICD-9 code of 295, 297, or 298), as having a psychotic disorder. The use of billing codes from electronic medical records to classify patients with psychotic illness has been validated, with a sensitivity of 91 percent and a specificity of 99 percent ( 22 ). After excluding 407 patients with ICD-9 codes for mood disorders, we were left with a comparison cohort of 3,618 outpatients with diabetes but no severe mental illness. Within this large comparison cohort were 24 patients (.66 percent) who were receiving antipsychotic medication. Detailed chart review by a board-certified psychiatrist (APW) led to the reclassification of three patients with schizophrenia. The remaining 21 patients (chart diagnoses of major depression, dementia, delirium, or mental retardation) were excluded from further analysis. The final sample sizes were 214 patients with schizophrenia or a schizophrenia-like condition (89 patients with schizophrenia, 118 with delusional disorder, three with paranoia, four with delusional disorder and paranoia; hereinafter called "schizophrenia" or the "schizophrenia group") and 3,594 patients without severe mental illness.

Measures

Demographic variables included age, gender, race and ethnicity, and marital status. The use of prescription psychotropic medications (antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines) was assessed by documentation in the medical record. Comorbid medical conditions were identified. The presence of hypertension was defined as having hypertension on the problem list or as having an antihypertensive medication, such as an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), an alpha blocker, a beta blocker, a calcium channel blocker, or a thiazide diuretic, on the medication list. The presence of hyperlipidemia was defined as having a problem list diagnosis, prescription of lipid-lowering agents (such as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, or "statins"; cholestyramine; colestipol; fenofibrate; gemfibrozil; or niacin), or the presence of elevated low-density lipoproteins (LDL greater than 100 mg/dL) or decreased high-density lipoproteins (HDL less than 40 mg/dL for men and less than 50 mg/ dL for women) among patients not taking a lipid-lowering agent. Current smoking was determined by inclusion on the problem list.

Treatment appropriateness was assessed with five primary measures: use of a hypoglycemic medication (alpha glucosidase inhibitor, biguanide, insulin, glitinide, sulfonylurea, or thiazolidinedione) for patients with a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level greater than 7 percent, use of an ACE inhibitor or ARB by all patients, use of an antihypertensive medication among patients with hypertension, use of a lipid-lowering agent among patients with hyperlipidemia, and use of aspirin by all patients. Each of these interventions is backed by clear evidence of efficacy for this population. As a composite, these are the five core treatments recommended as part of the intensified multifactorial treatment approach to the care of patients with diabetes ( 23 ). Adherence to this approach has been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events by 20 percent for this at-risk population ( 24 ). We also assessed the use of nutritional consultation, as indicated by at least one billed visit for this treatment approach.

Treatment effectiveness was assessed with seven primary measures, representing a composite set of criteria based on benchmarks established by the American Diabetes Association, the American Heart Association, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance for the care of patients with diabetes ( 25 , 26 , 27 ). These included percentage of patients with HbA1c less than 7 percent, percentage of patients with HbA1c less than 9 percent, percentage of patients with LDL less than 100 mg/dL, percentage of patients with LDL less than 130 mg/dL, percentage of patients with total cholesterol less than 200 mg/dL, percentage of patients with HDL greater than 40 mg/dL (men) or HDL greater than 50 mg/dL (women), and percentage of patients with blood pressure less than 130/80 mmHg. This collection of measures (for both appropriateness and effectiveness) has been used previously to assess the overall quality of diabetes care and has proved to be sensitive to differences in quality delivered to subgroups of patients ( 21 ).

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics were compared between the cohort without severe mental illness and the cohort with schizophrenia by Student's t tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical proportions. For comparisons in which the assumption of homogeneity of variance did not hold (based on Levene's test for equality of variances), comparisons were performed with Welch's approximate t test. Primary outcomes were analyzed with a logistic regression model to calculate odds ratios adjusted for gender, race, clinic site, and age. Statistical significance was defined a priori as p<.05, two-tailed. Note that laboratory values and blood pressure measurements were available on only a subset of the cohort; the total denominator is indicated when discrepant from the total cohort size. We conducted all statistical analyses using SPSS version 11.0.

Results

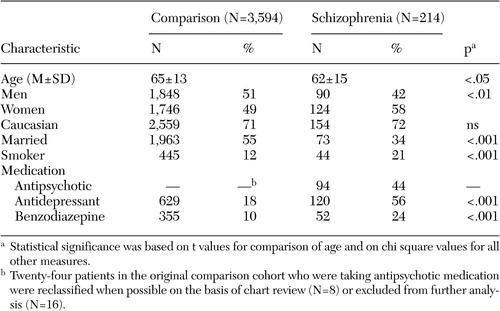

Of the total sample of 4,236 patients with diabetes, 214 (5 percent) had an ICD-9 diagnosis of schizophrenia or a schizophrenia-like condition. There were no significant differences in racial or ethnic makeup between the patients with psychotic illness and the larger comparison cohort of patients without severe mental illness. The group with schizophrenia comprised 154 Caucasians (72 percent), 38 Hispanics (18 percent), 17 African Americans (8 percent), and two Asians (1 percent). The comparison group comprised 2,559 Caucasians (71 percent), 480 Hispanics (13 percent), 284 African Americans (8 percent), and 111 Asians (3 percent) ( Table 1 ). There was a higher percentage of women within the group with schizophrenia (58 percent compared with 49 percent; χ2 = 7.1, df=1, p<.01), and the schizophrenia group was approximately three years younger on average than the comparison cohort (62 years compared with 65 years; t=2.41, df=234, p<.05). Patients in the group with schizophrenia were significantly more likely to be listed as a current cigarette smoker (21 percent compared with 12 percent; χ2 =12.1, df=1, p<.001), although it was interesting that this percentage was substantially lower than rates commonly reported with this population—up to 85 percent in some studies ( 5 ).

|

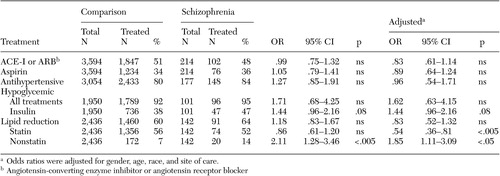

There were no significant between-group differences in treatment appropriateness on any of the five primary outcome measures ( Table 2 ). Thus patients with schizophrenia received an overall profile of pharmacological therapy related to cardiac risk factors that was similar to that for diabetic patients without severe mental illness. Nearly all patients with elevated blood glucose (HbA1c greater than 7 percent) were taking a hypoglycemic medication (92 percent of comparison patients and 95 percent of schizophrenia patients). However, patients with schizophrenia were slightly more likely than comparison patients to specifically receive insulin therapy (47 percent compared with 38 percent; adjusted odds ratio [OR]=1.44, p=.08). In addition, although the patients with hyperlipidemia in the two groups were equally likely to receive some form of lipid-lowering therapy, those with schizophrenia were significantly more likely to receive one of the older, nonstatin agents (14 percent compared with 7 percent; adjusted OR=1.85, p<.05).

|

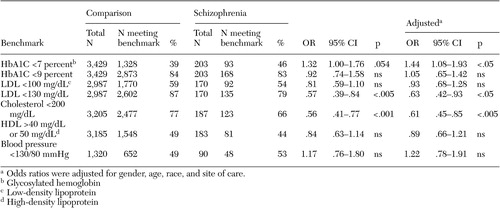

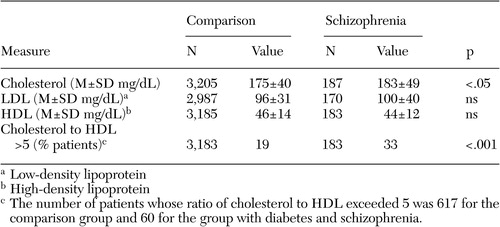

When compared with nationally recognized benchmarks, the level of treatment effectiveness was extremely high in both groups ( Table 3 ). For example, only 16 percent of comparison patients and 17 percent of schizophrenia patients had poor diabetic control (HbA1c greater than 9 percent), substantially lower than the 2003 national averages of between 23 and 49 percent reported by the National Committee for Quality Assurance ( 25 ). The percentage of patients attaining "tight" control of diabetes (HbA1c less than 7 percent) was also quite good and in fact was slightly higher in the group with schizophrenia (46 percent compared with 39 percent; adjusted OR=1.44, p<.05). There were, however, significant differences in the percentage of each group meeting the benchmarks for lipid control. Whereas 77 percent of the comparison population had cholesterol levels below 200 mg/dL, only 66 percent of the cohort with schizophrenia met this goal (adjusted OR=.61, p<.005). Similar discrepancies were seen in the percentage of patients having an LDL less than 130 mg/dL (87 percent compared with 80 percent; adjusted OR=.63, p<.05). Follow-up analyses revealed significant between-group differences in mean total cholesterol, as well as a greater percentage of patients with schizophrenia who had a ratio of cholesterol to HDL greater than 5—a marker of cardiac risk ( Table 4 ).

|

|

Additional post hoc analyses were performed to explore the potential contributors to the poorer lipid control among patients with schizophrenia, including both physician-related and patient-related factors. We found it interesting that the decreased rate of effective lipid control among patients with schizophrenia did not appear to be related to inadequate treatment. In fact, among patients with heightened cholesterol levels (greater than 200 mg/dL), patients with schizophrenia were more likely than comparison patients to be on a lipid-lowering agent (55 percent compared with 39 percent; χ2 =6.1, df=1, p<.05). Similarly, patients with schizophrenia and elevated cholesterol were more likely than comparison patients to be referred for nutritional consultation (27 percent compared with 17 percent; χ2 =6.7, df=1, p<.01). The type of pharmacological treatment received may have played a role, however. Effective cholesterol management (cholesterol less than 200 mg/dL) was found in 81 percent of all patients who were taking a statin medication (82 percent for the comparison cohort and 67 percent for the cohort with schizophrenia) but among only 55 percent of all patients on the older nonstatin lipid-lowering agents (58 percent for the comparison cohort and 35 percent for the cohort with schizophrenia).

We were unable to directly assess the role of medication adherence in the reduced effectiveness of lipid-lowering treatment among patients with schizophrenia. We did, however, have data on two related factors: rates for missed outpatient appointments and the total number of medications prescribed. Patients with schizophrenia were significantly more likely than comparison patients to miss at least one outpatient appointment (46 percent compared with 32 percent; χ2 =19.3, df=1, p<.001). Patients who missed at least one appointment were significantly more likely to have poor cholesterol control (27 percent compared with 22 percent; χ2 =10.5, df=1, p=.001), regardless of diagnostic group. Thus the higher rate of missed appointments by patients with schizophrenia may be a component in explaining the overall poorer cholesterol control. In a similar manner, the total number of prescribed medications was substantially higher among patients with schizophrenia (mean± SD=9.0±5.8) than among comparison patients (6.4±4.9) (t=5.7, df=234, p<.0001). A greater number of total medications was associated with poorer cholesterol control; patients with elevated cholesterol levels (that is, greater than 200 mg/dL) tended to be taking a higher number of medications (6.9±5.3 compared with 6.4±4.7; t=2.6, df=1650, p<.05), independent of group membership.

A planned examination of the impact of antipsychotic medication on the management of these cardiac risk factors was limited by the fact that only 94 of the 214 patients with psychotic illness (44 percent) had an antipsychotic medication listed in their chart. Patients documented as taking an antipsychotic medication were younger than patients with schizophrenia for whom there was no documentation (57±14 years compared with 67±15 years; t=5.0. df=212, p<.001) and were more likely to be Hispanic (22 percent compared with 13 percent; χ2 =12.5, df=5, p<.05). The two groups did not differ in gender balance, nor were there any statistically significant between-group differences in mean HbA1c, total cholesterol, LDL, or HDL. It is noteworthy that there were no statistically significant between-group differences on any of the five measures of appropriateness or the seven measures of effectiveness. These comparisons must be treated with caution, however, as smaller sample sizes may have led to type II errors or introduced bias into the analysis. In addition, we cannot rule out the possibility that documentation oversight may have artificially lowered the apparent prescribing rates.

Of the 94 patients taking antipsychotic medication, 71 were being treated with antipsychotic monotherapy (61 on second-generation and ten on first-generation neuroleptics) and 23 were being treated with combination therapy (11 taking two second-generation medications, 11 taking one first-generation and one second-generation medication, and one taking two first first-generation medications). Of the patients taking second-generation medication, 30 patients were taking risperidone, 23 olanzapine, 19 quetiapine, six clozapine, three aripiprazole, and two ziprasidone. The most frequently prescribed first-generation neuroleptic was haloperidol (six patients). The small number of patients taking first-generation neuroleptics and the small number of patients on any single medication precluded a statistically valid comparison of the specific impact of neuroleptic class or neuroleptic agent on the key clinical outcomes.

Finally, given the relatively advanced age of both cohorts, all of the analyses were rerun on a nonelderly sample (less than 65 years of age) to better approximate the demographic profile of the schizophrenia population seen in the typical outpatient mental health setting. In this analysis the mean age of the comparison group (N=1,757) was 54±9 years (range of 22-65 years) and the mean age of the schizophrenia group (N=123) was 52±9 years (range of 24-65 years). These analyses yielded results that were identical to those of the larger assessment. There were no significant differences on any of the five measures of appropriateness, but there were statistically significant differences on three of the seven measures of treatment effectiveness, the percentage of patients with an HbA1c less than 7 percent (comparison group, 33 percent; schizophrenia group, 45 percent; adjusted OR= 1.63, p<.05), the percentage of patients with an LDL less than 130 mg/dL (84 percent compared with 74 percent, adjusted OR=.55, p<.05), and the percentage of patients with a total cholesterol less than 200 mg/dL (73 percent compared with 60 percent, adjusted OR=.60, p<.05).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study sought to examine both the appropriateness and effectiveness of the medical management of cardiac risk factors for patients with diabetes and schizophrenia. Contrary to our initial hypotheses, we found that the appropriateness of treatment that these patients received was quite high and was not significantly different from a comparison cohort without severe mental illness. The effectiveness of this treatment was also impressive, meeting or exceeding the benchmarks established for diabetes management. That said, there were significant between-group differences in the effectiveness of lipid control, with fewer patients with schizophrenia than comparison patients meeting the benchmarks for cholesterol and LDL control. Thus despite statistically equivalent prescription rates in five domains of medical care, some patients with diabetes and schizophrenia may still not receive the quality of cardiac risk factor management that their counterparts without mental illness receive.

There are several potential reasons for this disparity in lipid management, including both physician- and patient-related factors. The simple explanation that patients with schizophrenia who had poor cholesterol control did not receive appropriate cholesterol-related care was not borne out by our secondary analyses. In fact, these patients were more likely than comparison patients with elevated cholesterol to receive a prescription for a lipid-lowering agent and to have at least one visit for nutritional counseling. It is possible, however, that other unmeasured aspects of treatment appropriateness (at the physician or health care systems level) could have played a role. The greater reliance on older, nonstatin lipid-lowering agents among patients with schizophrenia provides one example; these medications were associated with a lower likelihood of effective cholesterol control. The use of these medications, perhaps for cost considerations or more restrictive health care plans, could therefore be construed as inappropriate care. On the other hand, the elevated use of fibrates in a population prone to antipsychotic-induced hypertriglyceridemia may have been entirely appropriate; these drugs are a first-line treatment for this type of lipid profile ( 28 ). In the absence of triglyceride values and with limited data on antipsychotic use (see below), we cannot confirm this intriguing possibility.

We need to also consider the possibility that the patients with schizophrenia were less adherent than the comparison patients to their lipid-lowering medication. The greater rate of missed appointments in this population and their substantially more complex medication regimen both suggest that this may have been the case, as each of these factors was independently associated with poorer cholesterol control, and each has been associated with poorer medication adherence among patients with diabetes ( 29 , 30 ). Furthermore, there may be other patient-related factors, independent of medication adherence, that might account for the decreased effectiveness of lipid management in the schizophrenia cohort. Between-group differences in diet, exercise, and other lifestyle-related factors that can affect lipid levels, for example, may limit the benefits received from standard pharmacological treatment for this population ( 28 ).

These differences in lipid management notwithstanding, the quality of care received by the cohort with mental illness was surprisingly high, and on most measures the schizophrenia group did not differ from the comparison cohort. These findings, though contrary to our initial hypotheses, are in line with three other recent reports in which patients with diabetes and severe mental illness received care that was as good as a matched cohort of patients who did not have mental illness ( 16 , 31 , 32 ).

Desai and colleagues ( 16 ), using a large Veterans Affairs database, compared the appropriateness of care received by patients with diabetes and a psychiatric or substance use disorder with patients with diabetes and no mental illness. They found no differences on any of five clinical process measures (foot inspection, pedal pulses, sensory testing, retina examination, and HbA1c measurement) for patients with psychiatric illness, although patients with substance use disorders received poorer care on two of the measures (sensory testing and retina examination). Specific data for patients with psychotic illness were not presented. In a separate study, this group also found no differences in the rates of exercise and nutrition counseling delivered to the cohort with mental illness ( 32 ).

Dixon and colleagues ( 31 ), using a sample size and study design similar to that of our study, assessed the effectiveness of diabetes care for 100 patients with schizophrenia, 101 patients with a primary mood disorder, and 99 patients without mental illness by measuring the average HbA1c values achieved by these three groups. They found that glycemic control was actually better for the cohort with schizophrenia, a finding comparable with the higher degree of patients receiving "tight" glycemic control in our data set. In our data set, this unexpected finding may have been a result of the higher use of insulin therapy in the cohort with schizophrenia, a finding not seen in the Dixon study.

It is important to note that our data, obtained from patients treated under the umbrella of a prominent academic medical center in a large urban community, may not reflect the level of care received by many patients with schizophrenia. Indeed, a large percentage of patients with schizophrenia do not receive any medical care at all. Differences between our study and the study published by Jones and colleagues ( 15 ), which examined the quality of diabetes care for a large cohort of patients with mental illness across the state of Iowa, may reflect this fact. That study measured four aspects of appropriateness (HbA1c measurement, cholesterol measurement, retinal examination, and urine protein measurement) and found significant gaps across all measures in the mentally ill population. In addition, they found that patients in rural areas of Iowa were less likely than those in urban settings to receive high-quality care. Thus due caution should be exercised in generalizing from our results.

There are several limitations of our study, in addition to the cross-sectional design, which deserve mention. First, the group with schizophrenia was identified with ICD-9 billing codes from electronic medical records, not by psychiatric interview. Although the use of computer-recorded diagnoses of psychotic illness has been demonstrated to be sensitive and reliable, it is possible that a small percentage of patients were inaccurately included within the schizophrenia cohort. The removal of all patients in the comparison group who were taking antipsychotic medication and the exclusion of patients with primary mood diagnoses likely helped to minimize this possibility.

Second, the "schizophrenia" group actually comprised a number of psychotic diagnoses (including delusional disorder). Combining these subgroups of psychotic illness is a standard practice in cross-sectional health services research ( 15 , 16 ) and was essential to provide adequate statistical power for between-group comparisons. Nevertheless, the inclusion of these other illnesses, which in many cases are less severe than schizophrenia, may have improved the apparent quality of care received by this cohort.

Third, we chose to focus our contrast on patients with or without severe mental illness, a diagnostic distinction once again common to health services research. As a result, the comparison cohort may have contained a certain percentage of patients with other types of psychiatric illness, including anxiety disorders or substance dependence. It is possible that the inclusion of these patients within the comparison cohort worsened the apparent quality of care received by this group, minimizing between-group differences.

Fourth, we were unable to assess with confidence the specific effects of antipsychotic medication on these risk factors because of apparent gaps in the recording of psychotropic medications in the medical record. It is highly likely that the percentage of patients receiving antipsychotic medications was higher than 44 percent, but this information was unavailable, given that these patients may have been receiving psychiatric care outside of our system.

Conclusions

There are two main conclusions from these data. First, it is possible for patients with severe mental illness to receive medical care of very high quality, and second, despite apparently appropriate care, the effectiveness of this treatment may be lower for at least some of these patients. Additional work is necessary to better understand the impact of low-cost medication alternatives, the role of medication adherence, and the effect of critical lifestyle factors on the effectiveness of lipid-lowering management in the patient population with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Weiss is supported by career development award K23-MH-067019 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Grant is supported by career development award K23-DK-067452 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr Meigs is supported by a career development award from the American Diabetes Association. The authors thank Nancy Wong for assistance with data management and analysis.

1. Newman SC, Bland RC: Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 36:239-245, 1991Google Scholar

2. Harris EC, Barraclough B: Excess mortality of mental disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 173:11-53, 1998Google Scholar

3. Brown S: Excess mortality of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:502-508, 1997Google Scholar

4. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B: Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:212-217, 2000Google Scholar

5. Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al: Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:183-194, 2005Google Scholar

6. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al: Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care 27:596-601, 2004Google Scholar

7. Wilson P, D'Agostino R, Levy D, et al: Prediction of coronary heart disease risk using risk factor categories. Circulation 97:1837-1847, 1998Google Scholar

8. Gaede P, Pederson O: Intensive integrated therapy of type 2 diabetes: implications for long-term prognosis. Diabetes 53(suppl): S39-S47, 2004Google Scholar

9. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al: Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1334-1349, 2004Google Scholar

10. Casey DE, Haupt DW, Newcomer JW, et al: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: implications for increased mortality in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65(suppl):S4-S18, 2004Google Scholar

11. Newcomer JW, Nasrallah HA, Loebel AD: The Atypical Antipsychotic Therapy and Metabolic Issues National Survey. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 24(suppl 1):S1-S6, 2004Google Scholar

12. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al: Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Medical Care 40:129-136, 2002Google Scholar

13. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al: Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA 283:506-511, 2000Google Scholar

14. Levinson Miller C, Druss BG, Dombrowski EA, et al: Barriers to primary medical care among patients at a community mental health center. Psychiatric Services 54:1158-1160, 2003Google Scholar

15. Jones LE, Clarke W, Carney CP: Receipt of diabetes services by insured adults with and without claims for mental disorders. Medical Care 42:1167-1175, 2004Google Scholar

16. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al: Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the Veterans Health Administration. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1584-1590, 2002Google Scholar

17. Frayne SM, Halanych JH, Miller DR, et al: Disparities in diabetes care: impact of mental illness. Archives of Internal Medicine 165:2631-2638, 2005Google Scholar

18. Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Jeste DV: Adherence to antipsychotic and nonpsychiatric medications in middle-aged and older patients with psychotic disorders. Psychosomatic Medicine 65:156-162, 2003Google Scholar

19. Dickerson FB, Goldberg RW, Brown CH, et al: Diabetes knowledge among persons with serious mental illness and type 2 diabetes. Psychosomatics 46:418-424, 2005Google Scholar

20. Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, et al: The relationship of depressive symptoms to symptom reporting, self-care and glucose control in diabetes. General Hospital Psychiatry 25:246-252, 2003Google Scholar

21. Wexler DJ, Grant RW, Meigs JB, et al: Sex disparities in treatment of cardiac risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:514-520, 2005Google Scholar

22. Nazareth I, King M, Haines A, et al: Accuracy of diagnosis of psychosis on general practice computer system. British Medical Journal 307:32-34, 1993Google Scholar

23. Gaede P, Vedel P, Parving HH, et al: Intensified multifactorial intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria: the Steno type 2 randomised study. Lancet 353:617-622, 1999Google Scholar

24. Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, et al: Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine 348:383-393, 2003Google Scholar

25. State of Health Care Quality Report: Comprehensive Diabetes Care, 2003. Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality AssuranceGoogle Scholar

26. Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, et al: Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 100:1134-1146, 1999Google Scholar

27. American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 24(suppl):S33-S43, 2001Google Scholar

28. Meyer JM, Koro CE: The effects of antipsychotic therapy on serum lipids: a comprehensive review. Schizophrenia Research 70:1-17, 2004Google Scholar

29. Karter AJ, Ackerson LM, Darbinian JA, et al: Self-monitoring of blood glucose levels and glycemic control: the Northern California Kaiser Permanente diabetes registry. American Journal of Medicine 111:1-9, 2001Google Scholar

30. Rubin RR: Adherence to pharmacologic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Medicine 118(suppl):27S-34S, 2005Google Scholar

31. Dixon LB, Kreyenbuhl JA, Dickerson FB, et al: A comparison of type 2 diabetes outcome among persons with and without severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 55:892-900, 2004Google Scholar

32. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al: Receipt of nutrition and exercise counseling among medical outpatients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Journal of General Internal Medicine 17:556-560, 2002Google Scholar