Use of Environmental Supports Among Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

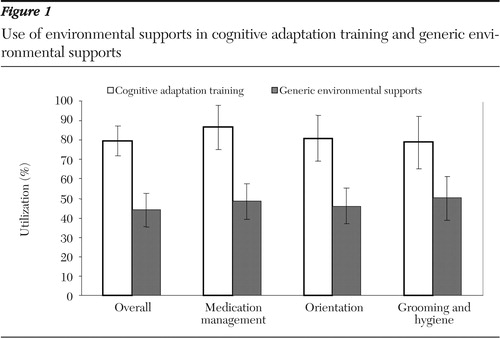

OBJECTIVE: Cognitive adaptation training is a psychosocial treatment that uses individually tailored environmental supports, such as signs, calendars, hygiene supplies, and pill containers, to cue and sequence adaptive behavior in the client's home environment. Generic environmental supports offer a less costly treatment that provides a predetermined package of helpful supports to clients at the time of their routine clinic visit. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of cognitive adaptation training. The study reported here examined the extent to which environmental supports are used by clients. METHODS: As part of an ongoing study, persons with schizophrenia were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: cognitive adaptation training, generic environmental supports, or assessment only. Rates of use of supports for the first three months of treatment were examined for the first 64 patients assigned to the first two groups. RESULTS: Rates of overall use averaged approximately 80 percent for cognitive adaptation training and 44 percent for generic environmental supports. Specific categories of supports were also significantly more likely to be used by patients who were receiving cognitive adaptation training. More than 66 percent of patients in cognitive adaptation training were classified as high users of supports (used more than 75 percent of supports provided appropriately), compared with only 13 percent of those who were receiving generic environmental supports. CONCLUSIONS: Environmental supports have been found to improve functional behaviors for patients with schizophrenia. However, supports are not likely to be used unless they are customized for individual clients and set up in the home environment.

Schizophrenia is characterized by cognitive deficits that predict the ability of afflicted individuals to perform basic activities of daily living and how well they will function in their social and occupational roles (1,2,3,4,5). A number of psychosocial treatments have been devised to address the cognitive impairments exhibited by persons with schizophrenia. Cognitive remediation seeks to directly improve cognitive functions that require attention, planning, problem solving, and memory skills (6,7,8,9,10). Rather than attempting to alter cognitive function per se, compensatory strategies attempt to bypass cognitive deficits by establishing supports in the person's environment that cue and sequence adaptive behavior. Our research group has applied environmental supports to persons with schizophrenia, with very encouraging results in a treatment we call cognitive adaptation training.

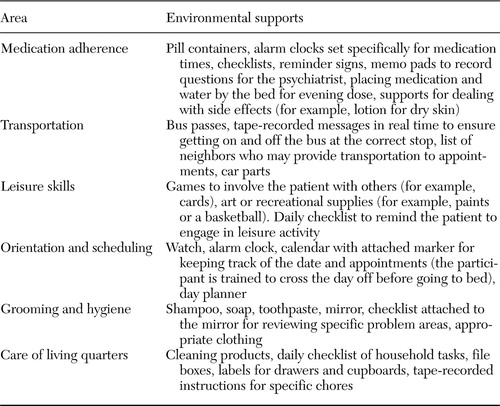

Cognitive adaptation training is a manual-driven series of environmental supports—such as signs, checklists, supplies, and organization of belongings—designed for each individual on the basis of cognitive strengths and weaknesses, specific functional problems, environmental barriers, and behavioral styles (11,12,13). These supports are offered to the client during home visits on a weekly basis to address specific problems, including in the areas of hygiene, care of the person's living quarters, adherence to medication regimens, and social or leisure activities. Although cognitive adaptation trainers use behavioral techniques, such as positive reinforcement, shaping, and antecedent control, unlike cognitive-behavioral therapy, cognitive adaptation training does not seek to change the emotions attached to thoughts.

The treatment is described in a series of articles (11,12,13), and the manual is available from the first author. Examples of some of the specific environmental supports used in cognitive adaptation training are listed in Table 1. We found that persons who received cognitive adaptation training were hospitalized less often and had better community outcomes than those in a control group or a treatment-as-usual group (12,13).

Although cognitive adaptation training is effective, a program that involves weekly home visits may be prohibitively expensive for underfunded, understaffed community agencies that serve persons with serious mental illnesses. Cognitive adaptation training has been shown to be less expensive than assertive community treatment but shares the problem that caseloads fill quickly (14). There is a great need to develop lower-cost treatments that use environmental supports to cue and sequence adaptive behavior.

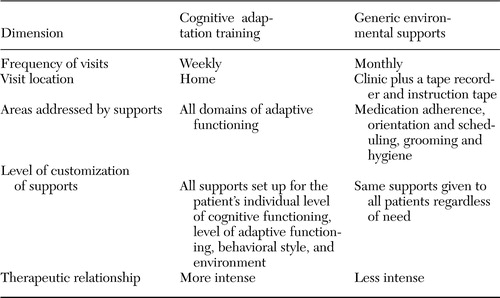

With this goal in mind, our research group developed strategies for using environmental supports in a more cost-effective manner. One strategy, generic environmental supports, provides environmental supports such as calendars and pill containers to clients at the time of their regular clinic visits. Clients are expected to set up the supports on their own, using a tape recording of the trainer's and client's discussion of how and where to use the supports in the home environment. The intensity of treatment varies between cognitive adaptation training and generic environmental supports. However, in previous studies we demonstrated that an intensive control condition involving weekly home visits by a therapist did not improve outcomes for persons with schizophrenia (13,14). Thus the intensity of cognitive adaptation training is not enough to account for improvements identified in previous studies. Differences between cognitive adaptation training and generic environmental supports, shown in Table 2, go beyond intensity. The comparatively higher cost of home visits makes it important to examine the extent to which a generic package of supports offered at clinic visits will be used by patients.

Although it is assumed that improvement in symptoms and adaptive functioning in cognitive adaptation training results from the use of environmental supports, few data are available on the use of these supports among persons with schizophrenia. Previous studies have not examined the use of environmental supports in a systematic manner (12,13). The extent to which individuals use the supports that cognitive adaptation training therapists set up in their homes and the extent to which individuals will use generic environmental supports that have been given to them at clinic visits remains unclear.

The purpose of this study was to examine rates of use of supports offered to persons with schizophrenia in these two treatments. Given the fact that supports in cognitive adaptation training are individually tailored and set up in the home environment, and their use is reinforced on weekly home visits, we hypothesized that patients in the cognitive adaptation training group would use a greater proportion of the environmental supports than those in the generic environmental supports group.

Methods

Participants

The study sample comprised 64 participants in an ongoing study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, of the use of environmental supports. The sample was recruited from February 2002 to September 2003. Outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were receiving medication and routine follow-up care at community clinics were approached about participating in this study at the time of their clinic visit and were asked to sign an informed consent document approved by the university's institutional review board. Participants met the following inclusion criteria: diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (15), age between 18 and 60 years, receipt of a second-generation antipsychotic medication other than clozapine, an absence of hospitalizations in the past three months, ability to provide evidence of a stable living environment for the past three months, and no current plans to move out of the area within the next two years. Individuals were excluded if substance abuse would have interfered with their study participation (for example, with assessment or treatment); if they had a documented history of significant head trauma, seizure disorder, neurologic disorder, or mental retardation; if they were currently being seen by an assertive community treatment team; or if they had engaged in violent behavior in the previous year.

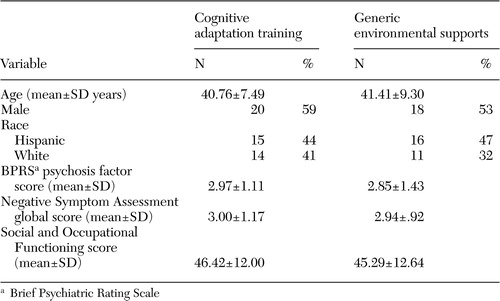

After a baseline assessment, participants who were monitored by community clinics for standard medication management were randomly assigned to one of three additional treatments: cognitive adaptation training, generic environmental supports, or assessment only. Among the first 68 participants who were assigned to either cognitive adaptation training (N=34) or generic environmental supports (N=34), three-month data were available for 29 and 31 patients, respectively. Three patients in the cognitive adaptation training group dropped out of the study, one withdrew after signing the informed consent form, one could not be contacted after completing initial assessments, and one moved out of the area. Of the remaining 31 patients, two could not be contacted by the utilization researcher during the first three months after repeated attempts, leaving 29 for whom utilization data were available in the cognitive adaptation training group. One patient who was receiving generic environmental supports withdrew consent to participate, and two patients could not be contacted by the utilization researcher after repeated attempts, leaving 31 patients for whom utilization data were available in the generic environmental supports group.

Assessments

Baseline assessments included the Expanded Version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (16), the Negative Symptom Assessment (17), and the Social and Occupational Functioning Scale (15).

Treatment groups

Cognitive adaptation training. Cognitive adaptation training is a manual-driven series of compensatory strategies based on neuropsychological, behavioral, and occupational therapy principals (11). Before participating in cognitive adaptation training, patients receive comprehensive behavioral, neuropsychological, functional, and environmental assessments. These assessment procedures are described in detail elsewhere (11). Treatment plans are based on two dimensions: level of apathy (poor initiation) versus disinhibition (distracted by irrelevant cues and information in the environment) and level of impairment in executive functions (the ability to plan and carry out goal-directed activities). Behaviors characterized by apathy can be altered by providing prompting and cueing to initiate each step in a sequenced task. For example, therapists may provide checklists for tasks that involve complex behavioral sequencing or place signs and equipment for daily activities directly in front of the patient, such as a checklist for medication placed on the refrigerator. Individuals who exhibit disinhibited behaviors respond well to the removal of distracting stimuli and behavioral triggers and to redirection. For example, a therapist may help to discourage taking of multiple doses of medication at the same time by placing pills in single-dose containers, or remove outdated medications to be stored elsewhere. Individuals with mixed behavior (apathy and disinhibition) are offered a combination of these strategies.

Individuals with greater degrees of executive impairment are provided with a greater level of structure and assistance and more obvious environmental cues (larger and more proximally placed). Individuals who have less impairment in executive functioning can perform instrumental skills adequately with less structure and more subtle cues. These general plans are adapted for individual strengths or limitations in other cognitive areas. Interventions are explained, maintained, and altered as necessary during brief (30-minute) weekly visits from a cognitive adaptation trainer. Detailed progress notes list all supports provided and their intended target behaviors.

Generic environmental supports. Generic environmental supports is a manual-driven series of environmental supports offered to patients at their regular clinic visit. The generic package is composed of the supports that were frequently used and described as helpful by clients in the cognitive adaptation training program on the basis of progress notes and store receipts. Supports selected for the generic package required minimal training and were designed to address three primary problems: medication adherence, orientation and scheduling, and grooming and hygiene. Supports included an alarm clock, a watch, bus passes, a checklist of everyday activities such as taking medication and showering, hygiene products such as shampoo and toothpaste, pill containers, and reminder signs—for example, "Did I take my medication?" or "Did I remember to brush my teeth?" A bookstore gift card is given to participants in an effort to promote leisure activity, and one of the items on the checklist is intended to prompt social behavior. However, these areas of functioning are not well addressed by generic environmental supports.

Therapists offered the same supports to all participants and provided instructions on how to use each item. The therapist discussed with the client where to place signs to get maximum benefit and how to use watches, alarms, and pill containers. The session was audiotaped, and the client was given both the tape and the tape recorder to replay the instructions any time. Once a month, the therapist called the client to ask whether the client needed any replacement supplies. If supplies were needed, the client picked them up from the clinic. For some patients, for the purposes of the study, supports were delivered to the client's home.

Utilization. Each month, a utilization researcher telephoned each client. The utilization reviewer used treatment notes and store receipts to determine all supports provided during the preceding one-month period for patients in cognitive adaptation training. From the therapist notes, the utilization researcher determined the intended function of each support offered. For patients who were receiving generic environmental supports, the utilization researcher used the original item list for the package and the therapist's notes regarding which items were supplied in the previous month. The researcher asked the participant whether he or she had used each support over the past seven days and exactly how the support was used. In an effort to prevent the participant from trying to make his or her therapist "look good," the participant was told at the beginning of each call that the information provided would not be shared with the cognitive adaptation training therapist or the generic environmental supports therapist.

On the basis of the information provided, the utilization researcher calculated a percentage use based on the intended use of the support. For example, if an item was intended to be used daily and it was used four out of seven days, the percentage use would be 57 percent. A mean percentage use for each contact was generated by averaging the percentages for each item, and then the contacts for the three-month period were averaged. Supports provided were also placed into categories, and a mean utilization percentage by category was calculated. Categories common to both treatments included medication adherence, orientation and scheduling, and grooming and hygiene. Categories were not mutually exclusive, and the same support could have been counted in more than one category. For example, a calendar may have been used to keep track of medication appointments as well as to keep oriented to day and date.

Data analysis

The three primary behavioral targets addressed in generic environmental supports—medication adherence, orientation and scheduling, and grooming and hygiene—were examined in both treatment groups. Differences in percentage use between the cognitive adaptation training group and the generic environmental supports group at three months were compared by using t tests for overall use of supports as well as for specific categories. To correct for multiple comparisons, we set the significance level conservatively at .01. Data were also examined by using nonparametric statistics, because the distributions of the individual categories of supports were not always normal. Because nearly identical results were obtained with both approaches, we report the results of the t tests below.

We used the intraclass correlation coefficient to examine whether the individual categories of supports could be combined into a meaningful composite score for overall percentage use.

Results

Descriptive and baseline data

Demographic characteristics of the two treatment groups are listed in Table 3. No statistically significant baseline differences were observed between groups in terms of age, gender, or ethnicity. Furthermore, clinical variables, such as level of psychotic symptoms, negative symptoms, and social and occupational functioning, did not differ significantly between groups at baseline. Baseline characteristics of participants for whom utilization data were available and those for whom data were not available did not differ significantly.

Rates of utilization

Mean utilization rates for overall supports and by categories are shown in Figure 1. Participants who received cognitive adaptation training had a higher mean percentage use of supports than those who received generic environmental supports. The differences between groups were statistically significant for overall supports (t=5.75, df=58, p<.001) and for each category (orientation and scheduling, t=4.78, df=56, p<.001;medication adherence, t=5.43, df=56, p<.001;and grooming and hygiene, t=3.23, df=46, p<.001). Degrees of freedom differ for specific utilization categories because cognitive adaptation training is customized for the individual, so not all participants in that group received all types of supports.

The intraclass correlation coefficient for the categories was .87, which suggests that the categories of support could be meaningfully combined into a composite score reflecting overall use. We classified participants as high or low utilizers on this overall utilization composite score on the basis of a cutoff of 75 percent. This is a commonly used cutoff in the medication adherence literature for schizophrenia, reflecting the idea that in a negotiated treatment, a person who is taking between 70 percent and 80 percent of the recommended dosage has good adherence to the treatment (18,19).

We found that more than 66 percent of patients in the cognitive adaptation training group (19 of 29) were high utilizers, compared with less than 13 percent of patients in the generic environmental supports group (four of 31) (Fisher's exact test, p<.001). Thus only a small percentage of patients in the generic supports group actually received a recommended "dose" of the treatment.

Clinical observations

Utilization problems in the generic environmental supports group appeared to have several origins. Some clients forgot to use the kit provided. Others did not like the brands or styles of products provided. Moreover, very limited social reinforcement was provided for the use of items. Clients undergoing cognitive adaptation training receive regular praise and other social reinforcement during weekly in-home visits.

Discussion and conclusions

Several methodologic limitations should be kept in mind. By necessity, the utilization researchers were aware of participants' treatment group assignment when asking about the use of supports provided. It is possible that participants exaggerated their use in an effort to make their therapist look good. However, store receipts for replacement of environmental supports and progress notes kept by therapists are consistent with the notion that use of supports was high among patients who received cognitive adaptation training. Generic environmental supports target primarily basic activities of daily living. An analysis of utilization or supports for higher-level behaviors for patients receiving cognitive adaptation training will be conducted once the study has been completed. It is also possible that supports may be used less frequently over the course of cognitive adaptation training treatment. This possibility will be investigated in follow-up studies.

High utilization levels in cognitive adaptation training suggest that the use of supports may be the key to the improvements in adaptive functioning that have been observed in previous studies. Future studies will need to examine this process-outcome relationship specifically. Generic supports provided in a clinic setting may improve behavior if the supports are used. Unfortunately, supports are unlikely to be used if they are not individualized, set up, trained, and maintained in the patient's home environment. It is unclear whether the higher rate of use in the cognitive adaptation training group was due to the individualization of supports; the training in the use of the supports in the home environment; the weekly visits that prompt, reinforce, and check the use of supports; or a combination of these procedures.

Future research is needed to tease out each of these factors. It is conceivable that weekly telephone calls in the generic environmental supports group may be enough to stimulate use by providing the social reinforcement and prompting necessary to form habits around the use of supports. In addition, offering a limited range of choice of item brand may prompt higher use. Additional research will be necessary to test these hypotheses.

Although previous studies have suggested that patients participating in cognitive adaptation training improved in terms of adaptive functioning more than those in the control conditions, ours is the first study to formally examine the degree of use of specific supports. Even though findings lend credence to the continued study of supportive environments for persons with schizophrenia, process-outcome relationships between the use of supports and adaptive functioning need to be specifically examined.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by grant R01-MH-61775-04 from the National Institute of Mental Health. During manuscript preparation, Dr. Velligan was supported in part by grant R01-MH62850-08 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, MSC 7792, San Antonio, Texas 78229 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Mueller is also with the Center for Health Care Services in San Antonio.

Figure 1. Use of environmental supports in cognitive adaptation training and generic environmental supports

|

Table 1. Examples of environmental supports used in cognitive adaptation training among persons with schizophrenia

|

Table 2. Differences between cognitive adaptation training and generic environmental supports for clients with schizophrenia

|

Table 3. Baseline characteristics of a sample of patients with schizophrenia who received cognitive adaptation therapy or generic environmental supports

1. Saykin AJ, Gur RE, Gur RC, et al: Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia: selective impairment in memory and learning. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:618–622,1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Gold JM, Harvey PD: Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 16:295–312,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC: Executive function in schizophrenia. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry 4:24–33,1999Medline, Google Scholar

4. Velligan DI, Mahurin RK, Diamond PL, et al: The functional significance of symptomatology and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 25:21–31,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry 153:321–330,1996Google Scholar

6. Benedict R, Harris AE, Markow T, et al: Effects of attention training on information processing in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:537–546,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al: Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: II. meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of social skills training and cognitive remediation. Psychological Medicine 32:783–791,2002Medline, Google Scholar

8. Medalia A, Revheim N, Casey M: The remediation of problem-solving skills in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:259–267,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Spaulding W, Reed D, Storzbach D, et al: The effects of a remediational approach to cognitive therapy for schizophrenia, in Outcome and Innovation in Psychological Treatment of Schizophrenia. Edited by Lewis S. West Sussex, England, Wiley, 1998Google Scholar

10. Wykes T, Reeder C, Corner J, et al: The effects of neurocognitive remediation on executive processing in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:291–307,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC: Two case studies of cognitive adaptation training for outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 51:25–29,2000Link, Google Scholar

12. Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC, Huntzinger CD, et al: A randomized controlled trial of the use of compensatory strategies to enhance adaptive functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1317–1323,2000Link, Google Scholar

13. Velligan DI, Prihoda TJ, Maples N, et al: A randomized single-blind pilot study of compensatory strategies in schizophrenia outpatients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 28:283–292,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Korell SC, Velligan DI, DiCocco M, et al: Assertive community treatment versus cognitive adaptation training: a cost comparison. Poster presented at the Winter Workshop on Schizophrenia, Davos, Switzerland, Feb 24 to Mar 1, 2002Google Scholar

15. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

16. Ventura J, Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, et al: Manual for the Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. International Journal of Methods Psychiatric Research 3:227–244,1993Google Scholar

17. Alphs L, Summerfelt A, Lann H, et al: The Negative Symptom Assessment: a new instrument to assess negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 25:159–163,1989Medline, Google Scholar

18. Adams J, Scott J: Predicting medication adherence in severe mental disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 101:119–124,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kamali M, Kelly L, Gervin M, et al: Psychopharmacology: insight and comorbid substance misuse and medication compliance among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 52:161–163,166,2001Link, Google Scholar