Rediversion in Two Postbooking Jail Diversion Programs in Florida

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Patterns of rediversion in two postbooking jail diversion programs in Florida were examined to better understand the extent to which diversion programs served repeating clients. Rediversion occurs when a former or current diversion program participant is booked into jail on a new charge and diverted once again through the same diversion program. METHODS: Data from 18 months of consecutive entries into the Hillsborough County jail diversion program (N=336) and Broward County mental health court (N=800) were examined. RESULTS: Similar rediversion patterns were observed for the two diversion programs. About one-fifth of those who were diverted during the 18-month study period were rediverted at least once. Nearly half of those who experienced rediversion did so within 90 days of their initial diversion. Although fewer than 6 percent were rediverted two or more times, these individuals accounted for a disproportionately large number of overall diversions and were rediverted more quickly than those with only one rediversion. CONCLUSIONS: The diversion programs examined here appear to be experiencing a level of repeating clients similar to that observed in other pathways for accessing mental health treatment.

Arrest has become a common experience among some persons with severe mental illness. Surveys have found that between 38 and 52 percent of persons with severe mental illness have been arrested at least once (1,2), and studies of jail populations indicate that between 6 percent and 15 percent of detainees are persons with mental illness (3). The placement of persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons has been attributed to the adoption of restrictive civil commitment criteria, the closing of inpatient hospitals, and the lack of funding and support for community-based treatment services (3,4).

Jail diversion programs have garnered much attention as a strategy for reducing the presence of persons with mental illness in jails (5,6). Although a wide range of diversion strategies exist, all have at their core the idea that persons with severe mental illness should be treated through the mental health system, not the criminal justice system. The rationale for diversion is that individuals who come into contact with the criminal justice system because of behaviors that are more reflective of mental illness than criminality need mental health treatment, not arrest and incarceration (7,8).

Although diversion can occur either before or after arrest, this report focuses on diversion after arrest and booking. Postbooking diversion programs link jail detainees to mental health treatment resources in the community. Diversion may be undertaken either in lieu of prosecution or as a condition for reducing punishment (4,5). Diversion programs traditionally have been accessible to defendants charged with nonviolent misdemeanors or low-level felonies (9), although some diversion programs allow defendants charged with higher-level felonies to participate (10,11).

Postbooking jail diversion programs traditionally have operated through collaborative agreements between criminal justice, judicial, and mental health systems or agencies (5,12,13). In these programs, detainees are screened for mental illness at jail facilities, where initial treatment plans are developed for potential participants. Detainees are given the option of accepting the treatment plan and participating in the program or declining to participate. Diversion must also be agreed to by the prosecution, defense, and court. If all parties agree, diverted detainees are transferred or referred to community mental health facilities for treatment and follow-up planning. These cases are handled through regular court dockets, although nontraditional mental health dispositions are arranged. For example, diverted detainees may be sentenced to treatment as a condition of probation, may have charges dropped once treatment is arranged, or may have prosecution postponed and charges dropped once a specified period of treatment is completed.

Mental health courts have become an increasingly popular mechanism for attempting to achieve postbooking diversion. Although mental health courts vary considerably in structure and operating procedures (14), common features include court dockets devoted entirely to persons with mental illness, nonadversarial court proceedings, and voluntary participation (11,15,16). Mental health court participants may be linked to community treatment resources through the court and monitored by the court to encourage treatment compliance (15). Charges may or may not be dropped for participants in some mental health courts, although other courts require participants to plead guilty before participating (15).

Postbooking jail diversion programs are intended to benefit both targeted participants and the systems they enter. Individuals who are diverted are expected to benefit from access to treatment and symptom stabilization, which should lead to reductions in arrests, hospitalizations, and the need for services from the criminal justice and emergency mental health systems (10,17,18,19). Rearrest and rehospitalization have been the focus of research on existing diversion programs (9,10,18,20,21,22).

One diversion program outcome that has received little attention in existing research is rediversion. Rediversion is conceptualized here as a former or current diversion program participant being booked into jail on a new charge and being diverted once again through the same diversion program. Rediversion is undesirable in the same sense that rearrest is undesirable: both indicate that a program participant released into the community may have acted illegally. Like high rates of rearrest, high rates of rediversion may imply that diversion programs are not working, especially to the lay public and policy makers who may see them as evidence that programs prematurely release disruptive individuals into the community. Rediversion has the potential of being an especially sensitive policy issue for diversion programs. Because individuals who are rediverted are not only rearrested but diverted a second time, rediversion can be easily misconstrued as criminal behavior being dismissed on multiple occasions.

If the rationale for diversion is that persons with severe mental illness come into contact with the criminal justice system because of mental illness symptoms, some level of rediversion must be expected and accepted. Persons with mental illness served by diversion programs must be expected to experience symptom fluctuations that could possibly lead to a relapse. The issue of rediversion has not been addressed in existing studies of postbooking diversion programs (9,10,18,20,21,22,23).

The study reported here examined rediversion by describing the frequency of rediversion and the time between initial and subsequent diversions for participants in two postbooking jail diversion programs in Florida over an 18-month period. The frequency of rediversion provided information about the extent to which these programs experienced repeating clients. Time between diversions was examined to determine the extent to which those who were rediverted tended to come back immediately after release or after an extended period. Finally, available demographic information for defendants who did and did not experience rediversion was examined to help identify who experienced rediversion.

Methods

Program descriptions and data

Data from 18 months of consecutive entries into the Hillsborough County jail diversion program and Broward County mental health court were examined. Information from the most recent 18-month period for which complete data were available was used. Information available for all individuals was limited to a subject identifier, date of each entry, gender, and race. Information concerning criminal charges and psychiatric diagnoses was not available for this study. The data collection procedures for this research were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the University of South Florida.

Hillsborough County jail diversion program. The Hillsborough County jail diversion program (Tampa) operates through a collaborative agreement between criminal justice, judicial, and emergency mental health service systems in the county. Mental health workers at county jails evaluate detainees charged with misdemeanors and make official recommendations for diversion in court. If the judge agrees to diversion, detainees are released on their own recognizance to the community mental health center designated as the county's central short-term involuntary examination (that is, civil commitment) receiving facility. Transportation from the jail to the community mental health center is provided by the county. Participation in the diversion program is voluntary for detainees who do not meet criteria for involuntary examination, that is, evidence of harm to self or others or self-neglect. Detainees who meet short-term involuntary examination criteria must be transferred to the community mental health center for an examination, although they are given an opportunity to voluntarily participate in the diversion program if they are clearly competent to consent.

Detainees who are diverted undergo a psychiatric examination within 12 hours of arriving at the community mental health center. Only detainees meeting involuntary examination criteria are admitted for an extended period of inpatient evaluation and treatment. Others are discharged with referrals for outpatient treatment and prescriptions for psychiatric medications.

After evaluations are completed, the State Attorney's office agrees not to prosecute most program participants. Charges are pursued in a small number of cases, including some driving under the influence and battery cases. Diversion program participants are not monitored by the court for treatment compliance.

Data concerning Hillsborough County jail diversion entrants were obtained through a database maintained by the community mental health center at which all diversion program participants are evaluated after being released from jail. Data from individuals diverted during the 18-month period from January 1, 2002, through June 30, 2003, were included. During this period, 336 jail detainees were evaluated as part of the diversion program, accounting for a total of 444 diversions. The mean age at first diversion was 41.01±12.07, and a majority of diverted detainees were male (239 detainees, or 71 percent). Slightly more than half the diverted detainees were identified as Caucasian (186, or 55 percent), and most others were identified as either African American (99, 29 percent) or Latin or Hispanic (40, 12 percent).

Broward County mental health court. The Broward County mental health court (Ft. Lauderdale) is a preadjudication special jurisdiction court designed to identify and adjudicate cases in which persons with mental illness have been arrested for misdemeanors, ordinance violations, or criminal traffic violations. The court's operating procedures have been described in detail elsewhere (16,23). The nature and intensity of treatment linkages facilitated through the court vary. Some defendants are provided information about local services and are encouraged to seek treatment on their own; for others, the court may make appointments for treatment, provide transportation to treatment facilities, and periodically monitor treatment progress. Participation in the court is voluntary, and individuals who are incompetent to consent or in acute need of inpatient psychiatric treatment are stabilized before participating. Criminal prosecution is formally withheld for many participants, although as many as one-fourth are found guilty (23). Approximately one-third of the court's participants have their cases kept open and monitored by the court for a period of up to one year before final dispositions are determined (23).

Data concerning Broward County mental health court participants were obtained from a database maintained by the mental health liaison for the court. Data for the 18-month period from January 1, 2000, through June 30, 2001, were included. Eight hundred individuals participated in the court during this 18-month period, accounting for a total of 1,030 court cases. A majority of court participants were male (584 participants, or 73 percent). Slightly more than half of the court participants were identified as Caucasian (469, 59 percent), and most others were identified as either African American (262, or 33 percent) or Latino or Hispanic (55, or 7 percent).

Results

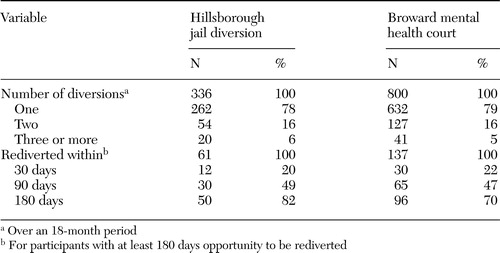

Rediversion was first examined by counting the number of individuals in each diversion program data set with only one diversion, two diversions, or three or more diversions. The percentage that each of these represented in their respective diversion program was then calculated (Table 1). Similar percentages were observed for both diversion programs, with more than three-fourths having only one diversion during the 18-month period. About 16 percent in each diversion program had two diversions. Fewer than 6 percent were diverted on more than two occasions.

Individuals with three or more total diversions accounted for a disproportionately large number of overall diversions. The 6 percent of Hillsborough County jail diversion program participants with three or more diversions accounted for 17 percent of all diversions. The 5 percent with three or more mental health court cases accounted for 14 percent of all cases.

Both diversion programs had several participants with an abnormally large number of diversions during the 18-month study period. Four Hillsborough County jail diversion program participants and six Broward County mental health court participants had five or more diversions. No participant in either program had more than seven diversions during the study period.

Time to rediversion

Time to rediversion was examined for individuals who had at least 180 days of opportunity to be rediverted within the time frame of data used for the study. This subset of participants was used to obtain the most accurate estimation possible of time to rediversion up to 180 days (approximately six months). Including participants with less than 180 days of opportunity to be rediverted would have resulted in an underestimation of the proportion that was rediverted within this timeframe. There were 228 Hillsborough participants and 520 Broward County participants who had at least 180 days of opportunity to be rediverted. The number of individuals who were rediverted at least once was 61 (27 percent) for the Hillsborough County program and 137 (26 percent) for the Broward County mental health court. Table 1 provides information about how quickly these individuals were rediverted. Similar patterns were found for the two diversion programs. Approximately one-fifth of those who reentered the diversion programs did so within 30 days of their initial diversions. Approximately half who experienced rediversion did so by 90 days, and about three-quarters of those who experienced rediversion did so within 180 days.

As would be expected given the findings reported in Table 1, the mean time to rediversion was similar across programs for those with at least a 180-day opportunity to reenter. The mean number of days to reentry was 115.31±105.47 for the Hillsborough diversion program and 135.80±121.73 for the Broward County mental health court.

A 2 (single versus multiple rediversions) × 2 (diversion program) analysis of variance was conducted to examine whether participants with multiple rediversions reentered the diversion programs more quickly than those with only one rediversion. This analysis compared the mean number of days to first rediversion for those with only one rediversion and those with more than one rediversion. The single significant finding from this analysis was a main effect indicating that those with multiple rediversions were indeed rediverted more quickly (mean number of days, 82.54±71.34) than those with only one rediversion (126.61±120.06, F=4.71, df=1, 238, p<.05), although the effect size for this effect was small (partial eta2=.02). No significant difference was found in the average time to rediversion for the two diversion programs.

Characteristics of rediverted and nonrediverted participants

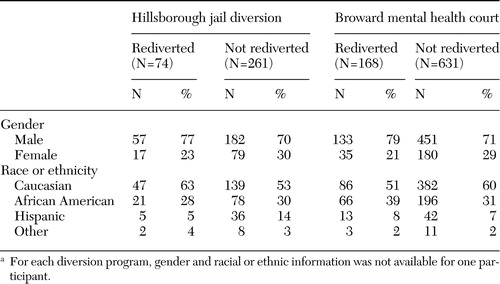

For each diversion program, individuals who were rediverted at least once were compared with those who were not rediverted on the available demographic characteristics of gender and race or ethnicity (Table 2).

For both diversion programs, the proportion of men was somewhat higher than the proportion of women in the rediverted group compared with the nonrediverted group. Whereas 70 to 71 percent of those with no rediversions were male, 77 to 79 percent of those with at least one rediversion were male. For both diversion programs, the effect size from this comparison was similar (phi=.07), indicating small overall differences in gender in the rediverted and nonrediverted groups. Phi is an effect size for contingency tables that is interpreted as a correlation coefficient. Values less than .15 indicate relatively small effects.

Racial or ethnic patterns in rediversion were less consistent across programs (Table 2). In Hillsborough County, the proportion of participants identified as Caucasian was slightly higher in the rediverted group. In Broward County, the proportion identified as African American was slightly higher in the rediverted group. However, extreme caution should be used when interpreting the percentages reported in Table 2 for race or ethnicity. Effect sizes for racial or ethnic differences in both diversion programs were small (phi<.08), and not enough individuals were identified as Latin or Hispanic to make reliable comparisons.

For Hillsborough County, the age of diversion program participants at their first rediversion during the 18-month period was also available for comparison. Those who were rediverted at least once were found to be somewhat older (mean age of 44.95±10.76 years) than those with only one diversion [39.87±12.21 years, t=3.24, df=329, p<.01, Cohen's d=.35].

Discussion

The limited data available for the two postbooking diversion programs indicate that they experienced similar patterns of rediversion during the 18-month study period. About one-fifth of those who were diverted were rediverted at least once. Nearly half of those who experienced rediversion were rediverted within 90 days of their initial diversion. Both diversion programs also appeared to provide services to a core group of individuals who experienced rediversion on multiple occasions and required a disproportionate amount of resources. These individuals also tended to experience rediversion somewhat more quickly than those with only one rediversion.

Because existing diversion program studies have not reported rates of rediversion, the extent to which the data from these two Florida programs indicate high, low, or expected rates of rediversion is unknown. One way to put rates of rediversion into perspective is to compare them with rates of reentry into the mental health system through other treatment access pathways. A common pathway into the mental health treatment system is through involuntary examination or hospitalization (that is, civil commitment).

Two studies examining rates of reevaluation and readmission over an 18-month period allow for a comparison with the rediversion patterns reported here. A recent study of initiations for involuntary examinations in Hillsborough County during an 18-month period revealed rates of reentry similar to those for rediversion in the county's jail diversion program (24). Seventeen percent of the 5,440 individuals who underwent involuntary examinations returned for a second involuntary examination during the 18-month study period. Approximately half the people who returned (54 percent) did so within 90 days. In the second study, an examination of 2,200 consecutive involuntary hospital admissions at a psychiatric treatment center in Philadelphia revealed that 18 percent returned for a second involuntary admission (25). Approximately 5 percent underwent three or more involuntary admissions. These rates of rehospitalization are nearly identical to the rates of rediversion observed in the two diversion programs. Taken together, data from these studies of involuntary examination and hospitalization suggest that the diversion programs examined here are not experiencing an unusually large proportion of "revolving door" clients, at least compared with what is known to exist in other pathways for accessing mental health treatment.

Conclusions

It is unreasonable to expect that any diversion program can completely eliminate subsequent arrests and, thus, the possibility of rediversion. However, being able to identify persons at highest risk ot rediversion may help diversion programs better allocate treatment and case management resources. Findings from the study reported here suggest that those who experience rediversion tend to be younger and male, although these effects were small. Future research should examine characteristics, including diagnosis, substance use, and index offense, that may provide more useful information about who is at risk for rediversion.

Dr. Boccaccini is affiliated with the departments of psychology and philosophy at Sam Houston State University, Box 2447, Huntsville, Texas 77341 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Christy and Dr. Poythress are affiliated with the Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute at the University of South Florida in Tampa, Florida. Dr. Kershaw is affiliated with Mental Health Care, Inc. in Tampa.

|

Table 1. Diversions and rediversions among participants in two jail diversion programs

|

Table 2. Race and gender of diversion program participants who were and were not rediverted over an 18-month perioda

aFor each diversion program, gender and racial or ethnic information was not available for one participant.

1. Holcomb W, Ahr P: Arrest rates among young psychiatric patients treated in inpatient and outpatient settings. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:52–57,1988Abstract, Google Scholar

2. McFarland BH, Faulkner LR, Bloom JD, et al: Chronic mental illness and the criminal justice system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:718–723,1989Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Lamb HR, Weinberger, LE: Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483–492,1998Link, Google Scholar

4. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, Reston-Parham C: Court intervention to address the mental health needs of mentally ill offenders. Psychiatric Services 47:275–281,1996Link, Google Scholar

5. Steadman HJ, Barbera SS, Dennis DL: A national survey of jail diversion programs for mentally ill detainees. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1109–1113,1994Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Torrey E, Steiber J, Ezekiel J, et al: Criminalizing the seriously mentally ill. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1992Google Scholar

7. Adams R: Mental health fact sheet: diverting people with mental illnesses who commit minor offenses from jail. Washington, DC, National Association of Counties, 1988Google Scholar

8. Walsh J, Holt D: Jail diversion for people with psychiatric disabilities: the sheriffs' perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 23:153–160,1999Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Naples M, Steadman HJ: Can persons with co-occurring disorders and violent charges be successfully diverted? International Journal of Forensic Mental Health Services 2:137–143,2003Google Scholar

10. Cosden M, Ellens JK, Schnell JL, et al: Evaluation of a mental health treatment court with assertive community treatment. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 21:415–427,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Goldkamp J, Irons-Guyn J: Emerging judicial strategies for the mentally ill in the criminal caseload: mental health courts in Fort Lauderdale, Seattle, San Bernadino, and Anchorage. Pub no NCJ 182504 Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, Apr 2000Google Scholar

12. Draine J, Solomon P: Describing and evaluating jail diversion services for persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:56–61,1999Link, Google Scholar

13. Steadman H, Morris S, Dennis D: The diversion of mentally ill persons from jails to community-based services: a profile of programs. American Journal of Public Health 85:1630–1635,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Steadman H, Davidson S, Brown C: Mental health courts: their promise and unanswered questions. Psychiatric Services 52:457–458,2001Link, Google Scholar

15. Griffin P, Steadman H, Petrila J: The use of criminal charges and sanctions in mental health courts. Psychiatric Services 53:1285–1289,2002Link, Google Scholar

16. Petrila J, Poythress N, McGaha A, et al: Preliminary observations from an evaluation of the Broward County Mental Health Court. Court Review 37:14–22,2001Google Scholar

17. Seide M: A jail diversion program. Psychiatric Services 50:269,1999Link, Google Scholar

18. Steadman HJ, Cocozza JJ, Veysey BM: Comparing outcomes for diverted and nondiverted jail detainees with mental illness. Law and Human Behavior 23:615–627,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Steadman H, Deane M, Morrissey J, et al: A SAMHSA research initiative assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 50:1620–1623,1999Link, Google Scholar

20. Bertman-Pate LJ, Burnett DM, Thompson JW, et al: The New Orleans forensic aftercare clinic: A seven year review of hospital discharged and jail diverted clients. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 22:159–169,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hoff RA, Baranosky MV, Buchanan J, et al: The effects of a jail diversion program on incarceration: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law 27:377–386,1999Medline, Google Scholar

22. Turpin E, Richards H: Seattle's mental health courts: early indicators of effectiveness. International Journal of Psychiatry and the law 26:33–53,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Boothroyd R, Poythress N, McGaha A, et al: The Broward Mental Health Court: process, outcomes, and service utilization. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 26:55–71,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Boccaccini M, Christy A, Poythress N, et al: Toward understanding reentry into postbooking jail diversion programs. Presented at the American Psychology-Law Society Annual Conference, Scottsdale, Ariz, Mar 2004Google Scholar

25. Sanguineti V, Samuel S, Schwartz S, et al: Retrospective study of 2,200 involuntary psychiatric admissions and readmissions. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:392–396,1996Link, Google Scholar