The Effectiveness of Skills Training for Improving Outcomes in Supported Employment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study evaluated whether a supplementary skills training program improved work outcomes for clients enrolled in supported employment programs. METHODS: Thirty-five recently employed clients with severe mental illness who were receiving supported employment services at a free-standing agency were randomly assigned to participate in either the workplace fundamentals program, a skills training program designed to make work more "successful and satisfying," or treatment as usual. Knowledge of workplace fundamentals (for example, identifying workplace stressors, problem solving, and improving job performance) was assessed at baseline and at nine months; employment outcomes and use of additional vocational services were tracked for 18 months. RESULTS: Clients in the workplace fundamentals group (N=17) improved more in knowledge of workplace fundamentals than those in the control group (N=18) at the nine-month follow-up, but the two groups did not differ in the number of hours or days worked, salary earned, or receipt of additional vocational services over the 18-month period. In general, clients in this study had higher educational levels and better employment outcomes than clients in most previous studies of supported employment, making it difficult to detect possible effects of the skills training intervention on work. CONCLUSIONS: Supplementary skills training did not improve work outcomes for clients who were receiving supported employment.

Abundant evidence has shown that supported employment is an effective strategy for improving the vocational outcomes of persons with severe mental illness (1). Supported employment—which emphasizes helping people find competitive jobs in integrated community settings, rapid job search and minimal prevocational preparation and assessment, and the provision of ongoing supports to help people maintain jobs or make the transition to new ones—has been shown to be more successful at helping people get jobs than a variety of other vocational rehabilitation approaches, including group skills training, psychosocial rehabilitation, and sheltered workshops (2). Supported employment is widely considered to be an evidence-based practice, and substantial efforts are under way to disseminate this model (3).

Despite the clear success of supported employment in improving vocational outcomes, there is still much room for improvement. One area of particular concern has been the relatively brief job tenure of many clients who obtain work in supported employment programs: job tenures range between 70 and 151 days and have an unweighted average of 114.7 days over one to two years (4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11). Although a variety of factors, such as cognitive impairment and symptoms (12), have been identified as contributing to brief job tenure and unsuccessful job terminations (being fired or quitting with no prospective job), social difficulties have been one common theme (13,14). For example, clients in supported employment programs may have difficulties in social situations, such as getting along with coworkers, interacting with customers, and responding to feedback and criticism from supervisors (15). It has been hypothesized that social skills training may help clients develop the critical skills for handling common social situations on the job, thereby prolonging job tenure and providing a more satisfactory work experience (16).

To address this need, Wallace and colleagues (17) developed a standardized skills training program aimed at improving social functioning in the workplace. Their program—workplace fundamentals—teaches basic information about work and solving workplace problems in a structured learning format by using the principles of skills training (18). Teaching is based on a trainer's manual and a videotape that demonstrates how to solve workplace problems; each client has a participant workbook.

One small (N=42) randomized controlled trial compared the effectiveness of adding the workplace fundamentals program to supported employment services for clients with severe mental illness and a history of recent unsuccessful job terminations (19). Over the 18-month follow-up period, compared with clients who received supported employment only, clients who participated in the workplace fundamentals program while in a supported employment program demonstrated greater acquisition of information and skills taught in the workplace fundamentals program, had significantly less job turnover, and were more satisfied with their jobs. However, the two groups did not differ in the number of hours worked or in the wages earned. The study suggests that the program may help clients with a history of unsuccessful job endings stay on the job longer. Aside from this study, two other controlled studies have evaluated the effects of skills training on vocational outcomes. Drake and colleagues (6) found that a group-skills training approach was not as effective as a supported employment model in improving vocational outcomes among 143 persons with severe mental illness, although changes in skills or knowledge were not evaluated. On the other hand, a small study by Tsang and Pearson (20) followed 97 clients with schizophrenia and found that a prevocational skills training group improved employment outcomes.

The study reported here was conducted to evaluate whether providing supplementary training on social skills for the workplace to clients who recently obtained work in a supported employment program would improve clients' vocational outcomes. We chose to focus on recently employed clients, because we were concerned that providing skills training to unemployed clients would delay their job search and evidence indicates that such delays worsen vocational outcomes compared with accelerated job search in supported employment (21). We hypothesized that clients who participated in the workplace fundamentals program would have a longer tenure for their first job, would work more hours, and would earn more wages during the follow-up period.

Methods

The study was conducted at Work, Inc., a program run by the parent company, Work Source, which is a publicly funded vocational rehabilitation agency that specializes in providing services to persons with severe and persistent mental illness. The study took place from May 1999 to December 2002.

Study participants

Clients were eligible to participate in the study if they were enrolled in supported employment services at Work, Inc., currently working at a job that was obtained within the past two months, willing to participate in a study of skills training, able to attend weekly groups if assigned to the skills training group, and willing to provide written informed consent. All clients met criteria for severe and persistent mental illness, as defined by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, and therefore no diagnostic inclusion or exclusion criteria were used. All eligible clients were approached by the employment specialist to participate in the study. Although no formal records were kept on the participation rate, approximately 20 percent declined because of personal reasons, such as not feeling as though they had enough time to participate in the workplace fundamentals group. The study and procedures were approved by the institutional review board of Dartmouth College.

Supported employment

Work, Inc., provides supported employment services to all clients who are referred from local community mental health centers and who express a desire to work. Any client who wants to work can be referred to Work, Inc., from their local mental health agency. Supported employment services are based on the principles outlined at the beginning of this paper. Vocational services are provided by career development specialists, each of whom provides the full range of employment services, including intake, assessment, career planning, job development, job coaching, and other supports. Career development specialists carry caseloads of approximately 15 clients. The model is designed to be able to provide an average of two hours of support per week per client, although in practice some clients require more time and others require less. The different specialists share job leads and provide cross coverage as needed. Coordination of vocational and mental health services is provided by informal contacts between the career development specialists and members of clients' treatment teams, usually by telephone, in most cases averaging once every two to four weeks and more frequently as necessary. Funding for Work, Inc., is provided by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health.

Fidelity to the principles of supported employment was not formally assessed but was monitored through regular contact with the supervisor and staff. On the basis of this contact, most of the elements of evidence-based supported employment programs were included in the vocational program, including rapid job searches, individualized job matches, and individualized and time-unlimited follow-along supports. However, the program did not have a close integration of mental health treatment and vocational services.

Workplace fundamentals program

Clients who were assigned to supplementary skills training participated in the workplace fundamentals program, a manualized intervention designed to teach clients skills for succeeding in the workplace. This program consists of nine different skill areas related to work, including how work changes your life, learning about your specific workplace, identifying workplace stressors, problem solving, managing mental health, managing physical health, improving job performance, making friends and appropriate socializing, and using supports and staying motivated. The sessions lasted approximately two hours. Skills were taught in sessions conducted weekly in groups of three to five clients. Approximately three to four months were required to complete the program. Monthly booster sessions were offered to help reinforce skill development. All missed group sessions were made up individually with clients.

Measures

Vocational outcomes for each job were tracked on a weekly basis and included hours worked and wages earned. Additional supported employment services (excluding participation in the workplace fundamentals group) were also tracked weekly in terms of number of hours of service provided to each client. Service hours included both direct client contacts and contacts with collaterals (for example, employers). Employment outcomes and vocational services were tracked for 18 months after baseline.

To evaluate whether the workplace fundamentals program was successful in teaching requisite knowledge to clients, the Workplace Fundamentals Knowledge Test was administered at baseline and nine months later. This test was conducted by interview and includes 65 items. Examples of items include the following: What are three resources you can use at work to get answers to a "don't know" you've identified? What are two common mental health symptoms that can interfere with work? And why is it important to understand "informal social rules" of your workplace? Possible scores on the test range from 0 to 66, with higher scores indicating better knowledge (17).

Procedure

Eligible clients were approached about the project by their career development specialist, given a description of the study, and invited to participate. Clients who expressed an interest in the study and provided written informed consent were then scheduled for an assessment with the Workplace Fundamentals Knowledge Test. After completion of this assessment, clients were randomly assigned to receive either supported employment services alone (treatment as usual) or supported employment services plus the workplace fundamentals program. Randomization was conducted with a computer-generated program at the New Hampshire Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center; staff members called one of the authors (DRB) to get the treatment assignment once a client met all eligibility criteria and had completed the baseline assessment. Clients were randomly assigned to the groups a mean of 56±37 days after obtaining a job. The intervention began after a cohort of four or five clients were assigned to the workplace fundamentals program. Clients who were working at the time that they consented to participate in the study but who had lost their jobs before the study began were nevertheless included in the group and tracked throughout the study.

Results

Thirty-five clients participated in the study; 28 (80 percent) were men, 34 (97 percent) were non-Hispanic white, one (3 percent) was Asian, 34 (97 percent) were single, and 30 (86 percent) had graduated from high school. The mean±SD age was 37.7±8.8 years. Twenty-three (66 percent) had schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, four (11 percent) had major depression or bipolar disorder, and eight (23 percent) had other psychiatric diagnoses.

Among the 35 clients in the study, 18 were randomly assigned to treatment as usual (control group) and 17 were assigned to the workplace fundamentals program. Chi square tests (for categorical variables) and t tests (for continuous variables) indicated no significant differences between the two groups in any demographic or diagnostic characteristics or in performance on the Workplace Fundamentals Knowledge Test at baseline. For the 18-month study period, clients held a total of 49 different jobs. All jobs were competitive—the job paid competitive wages in an integrated setting, was contracted by the client, and was not reserved for persons with disabilities (10). Fifteen clients (43 percent) worked the same job for the entire 18-month period. Of the remaining 34 jobs that ended, in four (12 percent) the client was laid off because the job was temporary or involved seasonal work, in 26 (76 percent) the client quit his or her job, in three (9 percent) the client was fired, and in one (3 percent) the reason for the job loss was missing. Information on disclosure of the client's psychiatric disorder was available for 39 jobs: in 34 (87 percent) of these jobs clients disclosed their disorder to their employer and in five (13 percent) they did not. No differences were found between the workplace fundamentals group and the control group in whether the ending of the first job was coded as successful (seasonal work, worked entire study, or quit to start another job) or unsuccessful (fired or quit).

Two sets of analyses were conducted to evaluate the effects of participation in the workplace fundamentals program on employment outcomes: intent-to-treat analyses and treatment-exposure analyses. Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted for all 35 clients. Four clients who were randomly assigned to the workplace fundamentals group did not attend group sessions and were thus not exposed to the intervention. These clients, along with two additional clients (one from the workplace fundamentals group and one from the control group) who lost their jobs before being randomly assigned to a group and did not work during the first six months of the study, were excluded from the treatment-exposure analyses. The results of the intent-to-treat analyses and the exposure analyses were very similar. Therefore, we present only the intent-to-treat analyses.

Workplace knowledge

To evaluate whether clients in the workplace fundamentals group improved their workplace knowledge more than clients in the control group, a repeated-measures analysis of variance was performed on the Workplace Fundamentals Knowledge Test scores at baseline and at the nine-month assessment, with the group as the independent variable. There was a significant group-by-time interaction (F=11.02, df=1, 15, p<.005), indicating that clients in the workplace fundamentals group improved more in their workplace knowledge at the nine-month assessment than clients in the control group (mean±SD score at baseline of 16.4±13.8 for the workplace fundamentals group and 19.7±8.6 for the control group; mean score at nine months of 35.2±14.1 for the workplace fundamentals group and 19.8±12.3 for the control group).

Employment outcomes

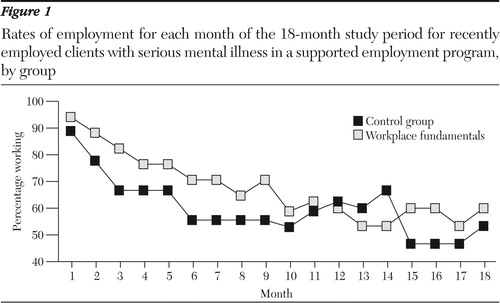

First, for each of the 18 months of the study, we plotted the percentage of clients in the two groups who were working. As can be seen from Figure 1, in 15 of the 18 months of follow-up, there was a trend for a higher proportion of clients in the workplace fundamentals group to be working, compared with those in the control group. The employment rates between the two groups over time were compared by using generalized estimating equations (GEE) analysis (22). GEE is an approach used to analyze correlated longitudinal data that can accommodate missing data, assuming that they are missing completely at random. GEE is similar to mixed-model linear regression, although the former has more restrictive assumptions concerning missing data than the latter. An advantage of GEE is that it can be used to analyze binary data, whereas mixed-model linear regression requires continuous data. The GEE analysis indicated a significant effect for time, Z=-3.19, p<.001, but not for group. The odds ratio for the group effect was 1.42, indicating that the odds of working in the workplace fundamentals group were 42 percent higher than the odds of working in the control group. This corresponds to an effect size of .21 (23,24). Thus the work rates of both groups decreased significantly over time, but the rates did not differ by group.

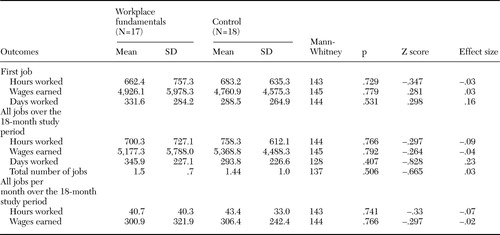

Second, we compared the cumulative hours worked, the cumulative wages earned, average job duration (in days) for the first job (beginning on the day that job began, before randomization), and all jobs held throughout the study. In addition, because five participants were missing some data on work during the follow-up period, we also compared the workplace fundamentals group and the control group on the number of hours worked and the wages earned per month in the study. Because the employment data were rather skewed, we compared the groups by using Mann-Whitney tests. As shown in Table 1, none of these tests were statistically significant, indicating that the groups did not differ in employment outcomes.

The job tenures for the first job for clients in both groups were relatively long (331.6 days for the workplace fundamentals group and 288.5 days for the control group), compared with the average of 114.7 days in previous studies of supported employment (4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11). We explored whether the study design, which required recently employed clients to wait an average of one to two months before randomization, may have biased the sample toward including clients with longer job tenures, because those with very short tenures might have not been referred to the study or may have chosen not to participate. To evaluate this possibility, we examined the average job tenure over 1.5 years for all clients who obtained work at Work, Inc. Between 1998 and 2004 the average job tenure was 315.2 days for 119 clients enrolled in services at Work, Inc. This rate of job tenure is comparable to the rates observed in this study and suggests that, compared with other clients at the same agency, the study sample was not biased toward clients with longer job tenures.

Vocational service use

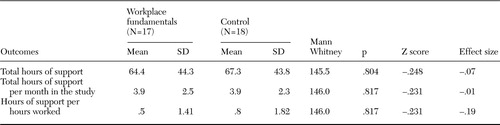

We explored whether participation in the workplace fundamentals group resulted in clients' needing fewer additional supported employment services than the control group. Vocational services were analyzed by using Mann-Whitney tests in terms of both the total hours of service provided, the total hours of services per month in the study, and the number of hours of service per hour worked. As shown in Table 2, similar to the employment outcomes, none of these analyses were statistically significant, indicating that the two groups were comparable in the amount and intensity of employment services provided.

Discussion and conclusions

Clients who participated in the workplace fundamentals program improved significantly more on the Workplace Fundamentals Knowledge Test than those who received supported employment alone, demonstrating that the program was successful in teaching the targeted information about work, although skills were not formally assessed. However, although there was a trend for more clients in the workplace fundamentals group to be working during the 18-month follow-up period, it was not statistically significant. Furthermore, the number of hours worked and the wages earned, either for the first job or all jobs held over the 18 months, did not differ between the groups, nor did the amount or intensity of supported employment services delivered. Thus, contrary to our hypothesis, participation in the workplace fundamentals program did not appear to improve vocational outcomes among clients who received supported employment.

It is possible that the workplace fundamentals program is simply not an effective adjunct to supported employment in this population. However, two characteristics of the study sample suggest that this conclusion is premature. First, the participants had a relatively high level of educational attainment, with 86 percent having graduated from high school, compared with rates of high school completion in other supported employment studies, which ranged between 47 and 74 percent (6,7,10). Higher educational level has been linked to better employment outcomes among people with severe mental illness (25,26,27), suggesting that participants in our study may have been prone to work more than the average participant in previously studied supported employment programs. Second, the average job tenure for the first job was substantially longer in our sample (331.6 days for the workplace fundamentals group compared with 288.5 days for the control group) than in most other studies of supported employment, in which lengths of job tenure were between one-third and one-half of the lengths found here (6,7,810). Thus the higher educational level and longer job tenure of clients in this study suggest that these clients were less in need of supplementary skills training, at least in terms of improving employment outcomes, than clients in previous supported employment studies.

It is unclear why clients in this study had higher levels of education and longer job tenures than those in previous studies of supported employment. Similar to agencies in other studies, the agency where this research took place did not impose eligibility criteria on clients other than the desire for competitive employment, suggesting that the agency did not select for clients with stronger motivation to work or better employment prospects.

One potentially relevant difference was that this supported employment study took place at a separate free-standing vocational rehabilitation agency, rather than at a community mental health center where mental health treatment and rehabilitation services are co-located, like most other studies of supported employment (6,7,810). This separate location required clients to follow through on their desire to work by traveling to that agency. One study that compared different vocational rehabilitation models reported that 100 percent of clients who were randomly assigned to a supported employment program that was located at a mental health center received services, compared with 85 percent of clients who were randomly assigned to a free-standing psychosocial rehabilitation program and 75 percent of clients who were randomly assigned to a free-standing vocational rehabilitation vendor (10), suggesting that fewer clients may seek vocational services when they are offered at a different location than their mental health services. It is plausible that clients who are more motivated to work are more likely to follow through on this desire by traveling to a free-standing agency. Alternatively, mental health agencies may have referred clients to vocational services whom they believed had a greater work potential, such as clients with a stronger work history or higher levels of education.

Overall, employment rates for the two groups were high; more than 50 percent of the clients remained employed over the 18-month follow-up period, and job turnover was relatively low (an average of 1.5 jobs per client). These good outcomes suggest that many of the clients in the study were relatively skilled, highly motivated, or well matched with their jobs and that they did not need the workplace fundamentals program, which was designed to address common work-related difficulties among persons with severe mental illness. One previous study of the workplace fundamentals program (19) limited participation in the program to clients with a recent job failure (for example, getting fired) and found that the workplace fundamentals program improved job tenure for the first job and job satisfaction among clients with severe mental illness who received supported employment. The results suggest that reserving the workplace fundamentals program for clients who have recently experienced work-related difficulties may avoid the problem of providing the intervention to clients who do not need it.

One final comment concerns the issue of disclosure. A very large number of study participants chose to disclose their psychiatric disorder to their employer (87 percent), more than in some other supported employment studies (28). This finding raises the possibility that the effects of the workplace fundamentals program could be greater among clients who do not disclose their disability to employers. The work outcomes of nondisclosing clients may rely more on their workplace skills and less on the skills of their employment specialists (for example, coaching and negotiating work-related issues with employers), making them more likely to benefit from the skills-training focus of the workplace fundamentals program.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the sample was small, resulting in low power to detect effects of the workplace fundamentals program on employment outcomes. Clearly, larger-scale studies of the program are warranted. Second, information on job satisfaction was not obtained. It is possible that the workplace fundamentals program was effective in improving job satisfaction, which is one of its goals, despite the finding that there were no apparent effects on employment outcomes. Third, symptom and quality-of-life ratings were not obtained, so it was not possible to evaluate whether the workplace fundamentals program was helpful to a subgroup of clients. Although this study did not support the beneficial effects of skills training on improving vocational outcomes among clients who participated in supported employment, further research on this question is warranted.

Acknowledgment

The research was supported by grant MH-56147 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Mueser, Ms. Becker, Ms. Wolfe, Ms. Schiavo, and Dr. Xie are affiliated with the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, 105 Pleasant Street, Main Building, Concord, New Hampshire 03301 (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Aalto and Mr. Ogden are with Work, Inc., in Quincy, Massachusetts. Mr. Aalto is also with Work Source in Quincy. Dr. Wallace is with the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Figure 1. Rates of employment for each month of the 18-month study period for recently employed clients with serious mental illness in a supported employment program, by group

|

Table 1. Employment outcomes for recently employed clients with serious mental illness in a supported employment program, by group

|

Table 2. Additional supported employment services delivered over the 18-month study period to recently employed clients with serious mental illness in a supported employment program, by group

1. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313–322,2001Link, Google Scholar

2. Twamley EW, Jeste DV, Lehman AF: Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:515–523,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Mueser KT, Torrey WC, Lynde D, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for people with severe mental illness. Behavior Modification 27:387–411,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Gervey R, Bedell JR: Supported employment in vocational rehabilitation, in Psychological Assessment and Treatment of Persons with Severe Mental Disorders. Edited by Bedell JR. Washington, DC, Taylor and Francis, 1994Google Scholar

5. Shafer MS, Huang HW: The utilization of survival analysis to evaluate supported employment services. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 5:103–113,1995Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, et al: The New Hampshire Study of Supported Employment for people with severe mental illness: vocational outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:391–399,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Bebout RR, et al: A randomized clinical trial of supported employment for inner-city patients with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:627–633,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Lehman AF, Goldberg R, Dixon LB, et al: Improving employment outcomes for persons with severe mental illnesses. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:165–172,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Harvey PD, et al: Cognitive and clinical predictors of work outcomes in clients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 54:1129–1135,2003Link, Google Scholar

10. Mueser KT, Clark RE, Haines M, et al: The Hartford study of supported employment for severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 72:479–490,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wong KK, Chiu L-P, Tang S-W, et al: A supported employment program for people with mental illness in Hong Kong. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 7:83–96,2004Crossref, Google Scholar

12. McGurk SR, Mueser KT: Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and work in supported employment: a review and heuristic model. Schizophrenia Research 70:147–174,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Becker DR, Drake RE, Bond GR, et al: Job terminations among persons with severe mental illness participating in supported employment. Community Mental Health Journal 34:71–82,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Mueller HH: Employers' reasons for terminating the employment of workers in entry-level jobs: implications for workers with mental disabilities. Canadian Journal of Rehabilitation 1:233–240,1988Google Scholar

15. Mueser KT, Foy DW, Carter MJ: Social skills training for job maintenance in a psychiatric patient. Journal of Counseling Psychology 33:360–362,1986Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Tsang HW: Applying social skills training in the context of vocational rehabilitation for people with schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 189:90–98,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Wallace CJ, Tauber R, Wilde J: Teaching fundamental workplace skills to persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:1147–1153,1999Link, Google Scholar

18. Liberman RP, DeRisi WJ, Mueser KT: Social Skills Training for Psychiatric Patients. Needham Heights, Mass, Allyn and Bacon, 1989Google Scholar

19. Wallace CJ, Tauber R: Supplementing supported employment with workplace skills training. Psychiatric Services 55:513–515,2004Link, Google Scholar

20. Tsang HW, Pearson V: Work-related social skills training for people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:139–148,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Bond G, Dietzen L, McGrew J, et al: Accelerating entry into supported employment for persons with severe psychiatric disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology 40:91–111,1995Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Regression analysis for correlated data. Annual Review of Public Health 14:43–68,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Haddock CK, Rindskopt D, Shadish WR: Using odds ratios as effect sizes for meta-analysis of dichotomous data: a primer on methods and issues. Psychological Methods 3:339–353,1998Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Chacon-Moscoso S: Effect-size indices for dichotomized outcomes in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods 8:448–467,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Arns PG, Linney JA: Relating functional skills of severely mentally ill clients to subjective and societal benefits. Psychiatric Services 46:260–265,1995Link, Google Scholar

26. Lorei TW, Gurel L: Demographic characteristics as predictors of posthospital employment and readmission. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 40:426–430,1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Mueser PR: A prospective analysis of work in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:281–296,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Rollins AL, Mueser KT, Bond GR, et al: Social relationships at work: does the employment model make a difference? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 26:51–61,2002Google Scholar