Current Concepts in Pharmacotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This article describes current approaches to the pharmacologic treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and reviews the classes of pharmacologic agents used in the treatment of PTSD. Pharmacotherapy for PTSD that is comorbid with other psychiatric disorders is highlighted. METHODS: The primary-source literature was reviewed by using a MEDLINE search. Secondary-source review articles and chapters were also used. Results from studies of the psychophysiology of PTSD are outlined in the review to help inform treatment choices. The review gives more consideration to controlled studies than to open clinical trials. Recommendations for treatment are evidence based. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: A growing body of evidence demonstrates the efficacy of pharmacologic treatment for PTSD. The effectiveness of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors sertraline and paroxetine in large-scale, well-designed, placebo-controlled trials resulted in their being the first medications to receive approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of PTSD. Observation of psychophysiologic alterations associated with PTSD has led to the study of adrenergic-inhibiting agents and mood stabilizers as therapeutic agents. Controlled clinical trials with these classes of medication are needed to determine their efficacy for treating PTSD. Finally, the choice of medication for treating PTSD is often determined by the prominence of specific PTSD symptoms and the pattern of comorbid psychiatric conditions.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterized by reexperiencing, numbing and avoidance, and hyperarousal, with associated biological responses triggered by exposure to a markedly distressing traumatic event. Time-limited posttraumatic stress responses that do not persist or disorganize functioning are normal reactions to external threat, analogous to normal grief reactions, and often necessary for survival. These normal reactions have been described as the fight-or-flight response (1). Catastrophic stress—particularly when repeated and accompanied by prolonged peritraumatic panic, terror, horror or helplessness (2,3), or prolonged peritraumatic dissociation (4)—overwhelms adaptive biological and coping responses and increases the risk of PTSD. Because of persistent disturbances in biological and psychological responses to trauma, persons with chronic PTSD remain in a state of heightened readiness for fight or flight long after the threat has passed.

Biological alterations found among persons with PTSD include adrenergic hyperresponsiveness (5), increased thyroid activity (6), increased levels of corticotrophin-releasing factor (7), and, in some studies, low cortisol levels and increased negative feedback sensitivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis after the administration of low-dosage dexamethasone (8). Several of these biological changes favor memory overconsolidation and classical conditioning of triggers, thereby contributing to the development and perpetuation of PTSD (9).

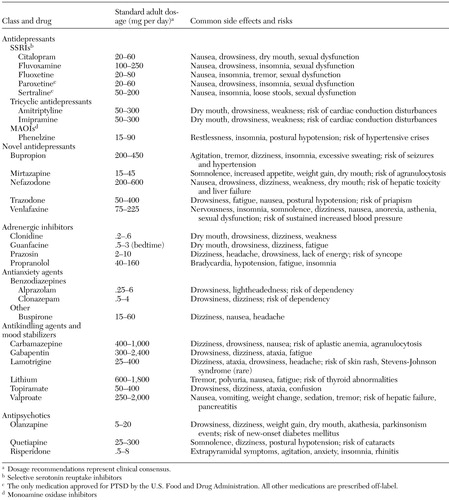

PTSD is one of the most common psychiatric disorders, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 7.8 percent (10). This review emphasizes data from pharmacologic treatment studies, results from studies of biological alterations in PTSD that help inform drug choice, and, when available, established guidelines for the pharmacologic treatment of PTSD. Dosage ranges and common side effects and risks associated with medications used to treat PTSD are listed in Table 1.

Methods

The primary-source literature was reviewed with use of a MEDLINE search. Secondary-source review articles and book chapters were also used. The terms "PTSD," "stress," and "stress response" were cross-referenced with a specific area of enquiry—drug or drug class, psychiatric diagnoses, and physiology. The search was conducted between January 2002 and January 2004. No time constraints were imposed on the studies reviewed. We draw on results from studies of the psychophysiology of PTSD to help inform readers about the rationale for the use of a particular class of pharmacologic agent. We describe clinical trial outcomes in terms of response rates, statistical significance (p<.05), and effect size. Effect size, as defined by Cohen (11), measures the magnitude of the treatment effect by taking the difference between the means of two independent groups of measures and dividing it by the standard deviation of the pooled standard deviation of both groups. A small effect size is .2; medium, .5; and large, .8. This review gives more consideration to controlled studies than to open clinical trials and examines them in more depth. Recommendations for treatment are based on the weight of the evidence available in the scientific literature.

Results and discussion

Antidepressants

Antidepressants are the most carefully studied medications and are currently the most frequently prescribed agents for the treatment of PTSD. A growing body of literature provides evidence-based justification for considering antidepressants as the pharmacologic treatment of choice for PTSD.

Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) were the first antidepressants to be used for the treatment of PTSD. The antipanic effect of these medications suggested that they would be helpful for the treatment of PTSD in light of the resemblance between panic attacks and severe PTSD arousal responses. Tricyclic antidepressants—amitriptyline, imipramine, and desipramine—have all been tested in controlled clinical trials using relatively small samples. The overall result can be described as modest symptom improvement from imipramine (effect size, .25) (12) and moderate improvement from amitriptyline (effect size, .64) (13); no benefit from desipramine was reported (effect size, .05) (14). Tricyclics were not found to be effective in alleviating avoidance and numbing. Tricyclics are not commonly used because of their disturbing side effects and potential toxicity relative to those of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and atypical antidepressants.

MAOIs, like tricyclic antidepressants, have antipanic activity. They have been used successfully to treat mixed states of anxiety and depression. A review by Southwick and associates (15) found that MAOIs were more effective than tricyclics for the treatment of PTSD. A very good global response was reported for 82 percent of phenelzine-treated patients, compared with 45 percent of patients treated with a tricyclic. Phenelzine has been the most commonly studied and used of the MAOIs. However, MAOIs must be used with caution because of the associated risk of hypertensive crisis. Reversible MAOIs are associated with less risk of hypertensive crisis. Their introduction resulted in a renewed interest in MAOIs. Neal and associates (16) reported, in an open-label trial, that the reversible MAO-A inhibitor moclobemide was associated with reduced symptoms in the three symptom categories that make up the PTSD diagnosis. However, moclobemide is not currently available in the United States.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. SSRIs enhance serotonin functioning in the central nervous system. Serotonin has a regulating effect on norepinephrine activity through its actions on the locus ceruleus, located in the brain stem. Low levels of central nervous system serotonin, as determined by cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), have been associated with impulsive aggressive and self-destructive behavior (17). Serotonin helps modulate excessive external stimuli and thus can reduce feelings of fear and helplessness.

SSRIs have proven to be effective for treating panic attacks, and fluvoxamine reduced anxiety induced by the norepinephrine-enhancing drug yohimbine among patients with panic disorder (18). These qualities have made SSRIs an attractive choice for PTSD treatment trials. Successful open-label and double-blind trials of sertraline (19,20,21), paroxetine (22), fluoxetine (23), fluvoxamine (24), and citalopram (25) have established SSRIs as the pharmacologic treatment of choice for PTSD. Sertraline and paroxetine are notable for having been assessed in large multisite randomized double-blind controlled trials.

On the basis of the therapeutic efficacy demonstrated in these trials, sertraline and paroxetine received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of PTSD. The two sertraline multicenter trials by Brady and colleagues (19) and Davidson and colleagues (20) treated a total of 395 civilian trauma victims and demonstrated a statistically significant response in all three PTSD symptom clusters as measured by the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-2). A positive treatment response was defined as a reduction of at least 30 percent in the combined CAPS-2 score plus a "much" or "very much" improved score on the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement (CGI-I) scale at the end of the study. By these criteria, 53 percent and 60 percent of sertraline-treated patients were responders in the two respective studies, compared with 32 percent and 38 percent of patients who received placebo. The effect sizes were modest: .3 for the Brady study and .4 for the Davidson study. In these studies, women had a significantly better response than men.

However, subsequent controlled studies with sertraline and paroxetine did not show a gender effect. In a double-blind clinical trial with 41 patients, Zohar and colleagues (21) found that sertraline was effective for both male and female Israeli combat veterans with PTSD. In a large fixed-dose placebo-controlled multisite study of 551 patients, Marshall and colleagues (22) demonstrated that paroxetine was effective for men and women with chronic PTSD. The patients were prescribed either 20 or 40 mg of paroxetine or placebo throughout the study. The CAPS-2 and the CGI-I were used as the primary outcome measures. Unlike in the Brady and Davidson studies, the CAPS-2 and CGI-I scales were not combined to determine clinical response rate.

Like sertraline, paroxetine was effective in treating each of the major symptom clusters of PTSD as measured by the CAPS-2. For the total study sample there was a 50 percent reduction in the total CAPS-2 score for paroxetine-treated patients, compared with a 33 percent reduction for the patients who received placebo. The reduction in the CAPS-2 score was associated with an effect size of .5—again, a modest treatment effect. Sixty-two per cent of patients who were treated with 20 mg of paroxetine and 54 percent who were treated with 40 mg had a much or very much improved rating on the CGI-I, compared with 37 percent in the placebo group, representing a highly significant difference between both paroxetine groups and the placebo group (p<.001). It is important to note that Vietnam combat veterans did not show significant benefit from SSRIs in controlled trials. Explanations for this finding include the severity and repetitive nature of combat trauma and perhaps a reluctance of veterans receiving a disability pension for PTSD to report improvement.

Almost all the SSRI studies were conducted over a period of 12 weeks or less. Beneficial effects are usually seen in four to six weeks. However, maximal benefit may take many weeks. Two important studies focused on the duration of treatment, and the results have informed clinicians about the need for long-term treatment to maximize and maintain a beneficial response to SSRIs. Londborg and associates (26) conducted a 24-week open-label trial of sertraline among 249 of the patients who had just completed the 12-week randomized controlled trials of sertraline versus placebo conducted by Brady and Davidson. Ninety-two per cent of the randomized controlled trial responders in the sertraline group maintained their beneficial response. An important finding during the course of this 24-week continuation study was that patients who had taken sertraline for the previous 12 weeks experienced an additional 31 percent decrease in symptoms. Also of significance, 58 percent of the patients who were classified as nonresponders in the initial 12-week study became responders. Although these observations are confounded by the effect of the passage of time and are not definitive, they suggest that a longer course of treatment with an SSRI may be needed to determine the drug's full beneficial effect.

Davidson and colleagues (27) conducted a separate 28-week discontinuation trial of sertraline treatment among 84 patients drawn from the Londborg study cohort who had a sustained beneficial response for 36 weeks. The relapse rate was 26 percent among patients who received placebo, compared with 5 percent among patients who continued to receive sertraline over the 28-week period. The first two months after discontinuation of sertraline were associated with the largest rates of clinical deterioration. These findings support the benefit of continuation therapy observed in the Londborg study and suggest the need to maintain treatment responders on SSRIs for at least a year. Discontinuation of an SSRI should be accomplished by gradual tapering with careful observation, especially during the first two months, to reduce the risk of relapse.

Novel antidepressants. Nefazodone and trazodone have 5-HT2 and α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist activity. Nefazodone is associated with less sexual dysfunction than are SSRIs (28). In a review of six open trials that included a total of 105 patients, nefazodone was found to reduce nightmares, generalized anxiety, and global ratings of PTSD (29). Response rates were assessed by examining reduction in PTSD symptoms as measured by the primary PTSD symptom scale used in each of the open clinical trials. On the basis of the criteria of a 30 percent, 40 percent, and 50 percent drop in severity of symptoms, the combined response rates were 46 percent, 34 percent, and 26 percent, respectively. As with SSRIs, the response was better among patients who had experienced civilian trauma than among those who had experienced combat-related trauma.

Nefazodone may be especially helpful for PTSD-related sleep disturbance. In a six-week study of 11 patients with PTSD, treatment with nefazodone increased the number of sleep hours and reduced the intensity and qualitative features of dream recall (30). Nefazodone is associated with an increased risk of hepatotoxicity and even liver failure, which has resulted in a "black box" warning from the FDA. Nefazodone treatment should not be initiated in cases of active liver disease or elevated serum transaminase concentrations. Trazodone is highly sedating, which makes it difficult to tolerate at a full antidepressant dosage. Trazodone has not proven to be significantly effective for treating core symptoms of PTSD (31). Trazodone can reverse insomnia that is sometimes caused by SSRIs such as fluoxetine and sertraline. An SSRI along with a low dosage of trazodone at bedtime is a widely used combination for treating chronic PTSD.

Other novel antidepressants have undergone a limited number of open clinical trials with small samples to determine their effectiveness for treating PTSD. Venlafaxine enhances the activity of serotonin, norepinephrine, and, to a lesser extent, dopamine neurotransmission. Venlafaxine, sertraline, and paroxetine were studied in an open clinical trial among Bosnian refugees (32). In a within-group comparison, venlafaxine was associated with statistically significant improvement in total PTSD symptom severity and Global Assessment of Functioning (p<.05) among five of 13 patients. Venlafaxine did not significantly improve symptoms of major depression. Eight of 13 patients dropped out of treatment because of side effects. The patients who received sertraline and paroxetine had a more robust reduction in PTSD symptoms (p<.001), and none dropped out of treatment. However, all study patients still met diagnostic criteria for PTSD at the end of this six-week study.

Mirtazapine enhances serotonin and noradrenergic neurotransmission. In a placebo-controlled double-blind trial, 29 patients received mirtazapine at a dosage of up to 45 mg a day or placebo in a ratio of 2:1 for eight weeks (33). The Short PTSD Rating Interview was the primary PTSD outcome measure; much or very much improved was considered a treatment response. Patients who received mirtazapine had a 65 percent response rate, compared with 22 percent of those who received placebo (p<.05). The treatment effect size was moderate at .49. However, the estimate of treatment effect in this study is imprecise because of the small sample. Mirtazapine was also helpful for anxiety as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, with a strong effect size of 1.14. Mirtazapine was well tolerated. Mirtazapine shows promise as an effective treatment for PTSD, especially for patients with comorbid anxiety disorders.

Bupropion is thought to have a weak norepinephrine reuptake blocking effect and some capacity to block the reuptake of dopamine. However, the mechanism of action for bupropion's antidepressant effect has not yet been elucidated. One open clinical six-week trial of bupropion was conducted among 17 combat veterans with PTSD (34). The blindly rated outcome measures included the CAPS, the CGI-I, the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A). Fourteen patients completed the study. Ten were rated as responders as measured by the CGI-I and the HAM-D. However, although there was a reduction in CAPS and HAM-A scores, the changes were not statistically significant. Symptoms of intrusion were noted to be unresponsive to bupropion. Although bupropion was well tolerated, it was clearly more helpful for depressive symptoms than PTSD symptoms.

Adrenergic-inhibiting agents. Adrenergic dysregulation is central to the biological changes found among persons with PTSD (5). People with PTSD have elevated levels of plasma norepinephrine at rest (35) and significant increases when exposed to trauma-related stimuli. The down-regulation of norepinephrine receptors in platelets is further evidence of increased circulating norepinephrine. Sustained periods of increased adrenergic activity are thought to increase the risk of PTSD by initiating a process in which there is overconsolidation of memories of the traumatic event (36). The ability of propranolol, a nonselective β-adrenergic blocker, to reduce the consolidation of emotional memories (37) suggests that immediate treatment with adrenergic-inhibiting agents after a severe traumatic event may be warranted.

In a double-blind controlled trial by Pitman and colleagues (38), 41 trauma victims were assigned to a ten-day course of either propranolol or placebo within six hours of the traumatic event. At one month, 18 percent of the patients who received propranolol met the criteria for PTSD as measured by the CAPS, compared with 30 percent of those who received placebo. At three months no significant differences were noted between the two groups; 13 percent of the patients who received propranolol and 11 percent of those who received placebo met the criteria for chronic PTSD. However, at three months, of the 22 patients tested, none of the patients who received propranolol were physiologic responders to reminders of the trauma, compared with 43 percent of those who received placebo.

Vaiva and associates (39), in a study that used a nonrandomized contrast group design, prescribed propranolol to 11 young adult trauma victims within 20 hours of the traumatic event for a period of seven days. They were compared with eight youths who declined to take propranolol. The two groups were matched on demographic characteristics, exposure, severity of injury, and peritraumatic responses. All the study participants had a resting heart rate higher than 90 beats per minute shortly after the traumatic event. Two months after the event the propranolol group had fewer PTSD symptoms. One patient in the propranolol group met the criteria for PTSD, compared with three patients who did not take propranolol. The results of these two studies suggest that propranolol may be a useful early intervention for preventing the development of PTSD.

By moderating central and peripheral adrenergic activity, adrenergic-inhibiting agents such as β-adrenergic blockers and α2-adrenergic agonists may reduce anxious arousal among patients with chronic PTSD. Famularo and colleagues (40) treated 11 children who had PTSD with propranolol in an off-on-off design of four-week blocks with a two-week drug taper between trials. The primary outcome measure was an inventory of childhood PTSD symptoms developed by the authors. Significant improvement during treatment (p<.005) and an increase in symptoms after treatment (p<.009) were noted. Eight of the 11 children experienced significantly reduced reexperiencing and arousal symptoms when they were taking propranolol compared with the periods when they were not taking propranolol.

Propranolol was studied in two small trials among adults with PTSD. Kolb and associates (41) treated nine Vietnam veterans and noted reduced trauma-related nightmares, intrusive memories, hypervigilance, startle response, and expressions of anger. However, Kinzie (42) reported that propranolol was not helpful in a sample of Cambodian refugees with PTSD.

Alpha2-adrenergic receptor agonists, such as clonidine and guanfacine, act at noradrenergic autoreceptors to inhibit the firing of cells in the locus ceruleus, effectively reducing the release of brain norepinephrine (43). Clonidine has shown promise among patients with PTSD in small open clinical trials and was used to treat severely and chronically abused and neglected preschool children with PTSD. It improved disturbed behavior by reducing aggression, impulsivity, emotional outbursts, and oppositionality (44). Insomnia and nightmares were also reported to be reduced.

Kinzie and Leung (45) prescribed the combination of clonidine and imipramine to nine severely traumatized Cambodian refugees with PTSD. Global symptoms of PTSD were reduced among six of the nine and nightmares among seven. Guanfacine produces less sedation than clonidine and thus may be better tolerated. In a case report, guanfacine reduced the trauma-related nightmares of a child with PTSD (46). A recently completed randomized double-blind trial among veteran patients with chronic PTSD showed that augmentation with guanfacine (N=29) was associated with no significant improvement in PTSD symptoms, mood, or subjective sleep quality compared with placebo (N=34).

Prazosin is an α1-receptor antagonist. Raskin and colleagues (47) studied the efficacy of prazosin for PTSD among ten Vietnam combat veterans in a 20-week double-blind crossover protocol with a two-week drug washout to allow for return to baseline (47). The CAPS and the Clinical Global Impressions-Change scale (CGI-C) were the primary outcome measures. Patients who were taking prazosin had a robust improvement in overall sleep quality (effect size, 1.6) and recurrent distressing dreams (effect size, 1.9). In each of the PTSD symptom clusters the effect size was medium to large: .7 for reexperiencing or intrusion, .6 for avoidance and numbing, and .9 for hyperarousal. The reduction in CGI-C scores (overall PTSD severity and function at endpoint) also reflected a large effect size (1.4). Prazosin appears to have promise as an effective treatment for PTSD-related sleep disturbance, including trauma-related nightmares, as well as overall PTSD symptoms.

Editor's Note: This paper is part of a series of psychopharmacology updates edited by Ewald Horwath, M.D. Contributions are invited to address the psychopharmacological treatment of psychiatric disorders. Papers should focus on integrating new treatments and on issues faced in the public sector, such as psychiatric and medical comorbidity, severe and persistent illness, and weighing of risks versus benefits of medications. For more information, please contact Dr. Horwath at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Drive, Unit 88, New York, New York 10032 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Antianxiety agents

Benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines potentiate the effects of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). The GABA-A receptor is the most common receptor in the brain and inhibits the activation of most neurons. Benzodiazepines reduce activity of the site of norepinephrine cell bodies in the brain, the locus ceruleus, as well as that of the fear center of the brain, the central nucleus of the amygdala. Benzodiazepines would appear to be a good choice for the treatment of PTSD. However, although benzodiazepines are often used for the treatment of PTSD, results of the few small studies that have been conducted suggest that they are of limited value in treating the core symptoms of PTSD. In an Israeli nonrandomized early intervention trial of accident and terrorism survivors, patients who received alprazolam or clonazepam were compared with a treatment-as-usual group who received no benzodiazepines (48). The 13 patients who received a benzodiazepine did not experience fewer symptoms of PTSD relative to 13 control subjects and at six-month follow-up exhibited a trend toward higher rates of PTSD. A possible explanation for these results is that benzodiazepines may interfere with the normal ability to desensitize conditioned fear responses to trauma cues. This interference may occur by altering optimal levels of working anxiety necessary for desensitization or by interfering with cognitive processing. A larger sample is needed to provide a more definitive answer as to the utility of benzodiazepines as an early treatment intervention.

Braun and associates (49) conducted a 12-week double-blind crossover trial with 16 patients who had chronic PTSD. A two-week drug washout allowed for a return to baseline before patients entered the second phase of the study. A 12-question PTSD scale, the Impact of Events scale, and the HAM-D and the HAM-A were the primary outcome measures. Five weeks of treatment with alprazolam was associated with a moderate effect on anxiety symptoms relative to placebo (effect size, .7). However, no statistically significant reduction of intrusion or of numbing and avoidance was observed. Also of note was the high dropout rate—three of seven patients who received alprazolam and three of nine who received placebo.

In a study by Risse and colleagues (50) of eight patients with combat-related PTSD and a history of alcohol abuse or benzodiazepine dependence, significant withdrawal symptoms occurred after gradual discontinuation of alprazolam. This finding supports the concern about the risk of dependence with alprazolam. Sustained-release formulations of alprazolam may prove safer and more effective.

Buspirone. Buspirone is a 5-HT1A receptor agonist used to treat anxiety disorders. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone has a low potential for abuse and withdrawal symptoms (43). Very few patients have been studied to determine the efficacy of buspirone for treating PTSD. In a small open trial of eight Vietnam veterans, buspirone was associated with significant improvements in reexperiencing, avoidance, and intrusion scores on the subscales of the Structured Interview for PTSD (p<.001) (51). Buspirone may be a safe and effective alternative to benzodiazepines for PTSD. However, its effectiveness for treating PTSD remains to be established.

Mood-stabilizing and antikindling agents

Sensitization and kindling of the limbic system has been proposed as a theoretical model for explaining the development of PTSD (52). Repeated exposure to a stimulus can lead to sensitization, observed as an enhanced physiologic response. Kindling is a spontaneous discharge resulting from sensitization. Limbic structures, such as the amygdala and the hippocampus, have a relatively low threshold for sensitization and resultant kindling. This mechanism is hypothesized to contribute to the increased physiologic reactivity observed among persons with PTSD. In addition, spontaneous intrusive imagery and flashbacks may be consequences of sensitization and kindling produced by repeated activation of conditioned fear memories (52).

Like antiadrenergic medications, antikindling and mood-stabilizing agents have the potential to prevent the development of sensitization and kindling in the first hours and days after exposure to a traumatic event or to moderate these phenomena once they are established. Drugs from this category that have been used in clinical trials to treat chronic PTSD include carbamazepine, valproate, topiramate, lamotrigine, lithium, and gabapentin. Carbamazepine, commonly used to treat seizure disorders involving the temporal lobe, has strong antikindling properties. In several small open clinical trials, carbamazepine was associated with reductions in intrusive traumatic memories and flashbacks and with improvements in insomnia, irritability, impulsivity, and violent behavior (53,54,55).

Valproate has a less potent antikindling action than carbamazepine. In one open clinical trial among Vietnam veterans with PTSD, ten of 16 patients showed improvement in arousal and avoidance but not intrusion (56). Topiramate is an anticonvulsant with GABA enhancement as its mechanism of action. Berlant and van Kammen (57) conducted an open trial among 35 patients with chronic PTSD who were unresponsive to previous pharmacotherapy. Topiramate administered alone or as adjunctive treatment was associated with reductions in PTSD symptoms, including severe nightmares.

Lamotrigine is a glutamate-inhibiting anticonvulsant. In a 12-week double-blind controlled trial among 15 patients with PTSD, five of ten patients for whom lamotrigine was prescribed were treatment responders, compared with one of four placebo recipients (58). Lamotrigine was associated with improvement in reexperiencing and in avoidance and numbing relative to placebo. However, because of the small sample, this finding was not statistically significant. Care should be taken in prescribing lamotrigine, because this drug is associated with a risk of serious rashes.

Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant that is structurally related to GABA. Its mechanism of action is unknown. It does not appear to carry the risk of serious side effects and toxicity that are seen with the other antikindling agents. In a retrospective review of gabapentin as adjunctive therapy for PTSD, gabapentin was found to be helpful for insomnia and also reduced the frequency of nightmares (59).

Lithium is a mood stabilizer with well-established efficacy for treating recurrent affective disorders. Lithium's mechanism of action is complex and includes alteration of serotonin transport. Two small open trials of lithium for the treatment of PTSD that enrolled a total of 27 patients have been reported (60,61). In both trials the arousal cluster of PTSD symptoms improved. Case studies and clinical trials suggest that the addition of lithium to standard treatments may be helpful for reducing anger and irritability among patients with PTSD (62).

Antipsychotics

Conventional and atypical antipsychotic agents have not been routinely used to treat patients with PTSD. Antipsychotics are useful in the treatment of PTSD with co-occurring psychosis. Also, in very severe cases of PTSD, characterized by disorganized behavior and marked dissociative symptoms, low-dosage antipsychotic medication can be a helpful adjunct to standard treatment. Antipsychotics are also used in instances of explosive, aggressive, or violent behavior. The results of recent studies suggest that atypical antipsychotics may be helpful for some of the core symptoms of PTSD. Risperidone, an antipsychotic with D2 and 5HT2 antagonism effects, was first noted in case reports to help PTSD-associated flashbacks and nightmares (63,64). Monnelly and colleagues (65) studied risperidone as adjunctive treatment in a six-week double-blind controlled study of 15 patients with combat-related PTSD. Outcome measures were the Patient Checklist for PTSD-MilitaryVersion (PCL-M) and the Overt Aggression Scale-Modified for Outpatients (OAS-M). Significant improvement in irritability (OAS-M), total PTSD symptoms, and intrusive thoughts (PCL-M) were noted.

Risperidone has also been studied among patients with PTSD and comorbid psychotic symptoms. Hamner and associates (66) used risperidone as adjunctive treatment among 40 combat veterans with PTSD in a five-week prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The primary outcome measures were the CAPS and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). A modest reduction in PANSS scores was observed among patients who received risperidone relative to those who received placebo (p<.05). Total CAPS ratings improved significantly in both groups but not between groups. Among patients who completed the trial, those who received risperidone also experienced modest improvement in the CAPS reexperiencing subscale relative to those who received placebo (p<.05), with a trend toward greater improvement relative to placebo at endpoint.

The results of these studies suggest that risperidone may be helpful in treating some of the core symptoms of PTSD as well as associated psychotic symptoms. Petty and colleagues (67) conducted an open clinical trial with olanzapine, an atypical antipsychotic that has serotonergic properties, among 48 veterans with a diagnosis of combat-related PTSD. Olanzapine was found to be effective in alleviating all three symptom clusters of PTSD, demonstrating a 30 percent reduction in overall CAPS scores. In a ten-week double-blind placebo-controlled trial among 15 patients, Butterfield and colleagues (68) found no between-group differences in relief of PTSD symptoms. A high placebo-response rate was observed: both the active treatment group and the placebo group showed a rate of symptom reduction comparable to that in other active drug treatment trials. In a double-blind controlled study of 19 veterans with combat-related PTSD, Stein and colleagues (69) found that olanzapine was associated with significantly reduced PTSD symptoms (effect size, 1.07) when used as an adjunctive treatment for PTSD with associated depression and sleep problems that had not responded well to an SSRI. Olanzapine also significantly improved depression (p<.03) and sleep disturbance (p<.01). The primary outcome measures were the CAPS, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Quetiapine is an antipsychotic that antagonizes α1-adrenergic, 5-HT2A, and histamine (H1) receptors in addition to its dopamine (D2) blocking effect. This profile suggests that quetiapine may be helpful for PTSD sleep disturbances as well as overall PTSD symptoms. Sokolski and colleagues (70) conducted a retrospective review of the charts of 68 veterans with combat-related PTSD. These patients were receiving low-dosage quetiapine as adjunctive treatment after failure to respond to at least two psychotropic agents. The effectiveness of quetiapine was judged by the proportion of patients who were much or very much improved in one or more of the DSM-IV criterion symptoms of PTSD: reexperiencing (35 percent), avoidance and numbing (28 percent), and arousal (65 percent). Sleep disturbance improved among 62 percent of the patients and nightmares among 25 percent.

Quetiapine was studied in a six-week open clinical trial among 20 veterans with combat-related PTSD (71). The CAPS and the PANSS were the primary outcome measures. Significant improvement in the total CAPS scores (p<.005) as well as the PANSS scores was noted among 18 of the 20 patients who completed the study. Thus far the clinical outcomes observed in studies of atypical antipsychotic agents suggest that these agents may be of benefit for patients with severe and treatment-resistant PTSD. Larger well-designed controlled trials are needed in order to determine the efficacy of atypical antipsychotic agents for this difficult-to-treat population.

PTSD comorbid with other psychiatric disorders

Posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with an exceptionally high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders. In the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), 79 percent of women and 88 percent of men with PTSD had at least one other psychiatric diagnosis, and 49 percent of women and 59 percent of men had at least three concurrent diagnoses (10). The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS) identified a psychiatric comorbidity rate of 98.9 percent among veterans with PTSD (72).

The issue of comorbidity is gaining more attention in the medical literature. An Expert Consensus Guideline Series includes sections that address the treatment of PTSD and comorbid disorders (73). Brady and coauthors (74) have written an excellent review of this topic. The conditions that are most likely to co-occur with PTSD are major depressive disorder, substance use disorders, conduct disorders, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, phobias, panic disorder, and mania. An important consideration in understanding the high prevalence of comorbidity among persons with PTSD is the significant symptom overlap between the diagnostic criteria for PTSD and other psychiatric conditions. This consideration is especially pertinent to depression and the anxiety disorders. However, there is evidence that these conditions are frequently independent responses to trauma exposure (75). It is clear that comorbidity needs to be considered in selecting a medication to treat PTSD. Despite the importance of comorbidity in making treatment choices, very few evidence-based studies are available to guide the clinician.

Affective disorders. The lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder among persons with PTSD is 48 percent for men and 49 percent for women. When comorbid depression occurs it follows the onset of PTSD in 78 percent of cases. Shalev and associates (75) observed that patients with co-occurring PTSD and major depressive disorder were more symptomatic and were less likely to respond to treatment than those with PTSD alone. A pharmacologic agent should target as many of the presenting conditions as possible to minimize polypharmacy. Antidepressants have demonstrated efficacy for both conditions. SSRIs are the first choice for this comorbidity (73).

In Southwick and colleagues' (15) meta-analysis of studies of patients treated with antidepressants for comorbid PTSD and major depressive disorder, PTSD symptoms responded independently of the antidepressant effect. In Marshall and colleagues' (22) paroxetine placebo-controlled fixed-dose study, patients with and without comorbid depression showed significant reduction in PTSD symptoms, but those who did not have comorbid depression had a more robust response. This finding is consistent with Shalev's observation. If a patient is not responding to SSRI treatment, a switch to an alternative class of antidepressant should be considered. In instances of partial response, unresponsive symptoms can be targeted with the addition of another agent—for example, trazodone for insomnia, adrenergic-inhibiting agents for arousal symptoms, and an antidepressant augmenting strategy for unresponsive depressed mood.

Persons with PTSD have a greater risk of having bipolar disorder than those who do not have PTSD: 10.4 times as great for men and 4.5 times as great for women (10). Treating the comorbid bipolar disorder is a high priority. Thus a mood stabilizer is the first class of medication to consider. Valproate and lithium are the most commonly prescribed mood stabilizers for bipolar disorder. Carbamazepine is also a consideration as a second-line choice. Valproate, lithium, and carbamazepine have been shown to relieve PTSD symptoms in open clinical trials. No studies have been conducted of the efficacy of these agents when PTSD and bipolar disorder occur together. Both conditions may not respond to a single agent. In circumstances in which PTSD symptoms have not responded to a mood stabilizer, the choice of an antidepressant to augment treatment, especially a tricyclic antidepressant, is tempered by the concern that it may carry a risk of precipitating a manic episode. The use of an adrenergic-inhibiting agent or an atypical antipsychotic is a consideration in these instances.

Anxiety disorders. As with depression, there is a high co-occurrence of anxiety disorders among persons with PTSD. The NCS revealed a significant increase in the lifetime prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, simple phobia, social phobia, and agoraphobia among persons with PTSD compared with those who did not have PTSD (10). Breslau and colleagues (76), in a study of civilian women with PTSD, found a prevalence of 55 percent for other anxiety disorders. In the NVVRS, both men and women with PTSD had a significantly higher current and lifetime prevalence of each of the anxiety disorders than veterans without PTSD (72). The one exception was current obsessive-compulsive disorder among women.

The high prevalence of comorbidity may be partially explained by the considerable overlap between PTSD symptoms and symptoms of the other anxiety disorders, which can lead to the overdiagnosis of PTSD or the other anxiety disorders. Diagnostic assessments that include an inquiry into how symptoms may be associated with trauma-related cues can help clarify the diagnostic confusion (77). The NCS finding that anxiety disorders were more likely to be present before the occurrence of PTSD rather than to develop as a consequence of PTSD supports the idea that other anxiety disorders commonly coexist with PTSD as distinct conditions. A personal or family history of anxiety disorder is also an established risk factor for PTSD (78,79). At this time, very few clinical studies are available to guide choices for the pharmacologic treatment of PTSD comorbid with other anxiety disorders. As with depression, the pharmacologic treatment for most of the anxiety disorders is similar to that for PTSD, which allows the clinician to minimize the use of multiple medications when treating this comorbidity.

Panic attacks commonly co-occur with PTSD, their onset often occurring after the development of PTSD. People with PTSD have three to four times the risk of developing panic attacks in their lifetime compared with those who do not have PTSD (10). The co-occurrence of these conditions increases the likelihood of spreading phobias, which increases dysfunction and treatment resistance. Michelson and colleagues (80) noted that the presence of PTSD symptoms of dissociation increase the risk of agoraphobia developing secondary to panic attacks. These findings highlight the importance of treating PTSD and panic disorder symptoms concurrently.

The Expert Consensus Guideline series recommends psychotherapy plus medication as the first-line treatment (73). Exposure-based treatment for PTSD may be difficult in the presence of panic disorder, because trauma-related cues may precipitate a panic attack. Cognitive-behavioral treatment or medication treatment, or both, may be necessary for patients with panic disorder before exposure-based treatment for PTSD is attempted. Four classes of medications have been found to be effective for the treatment of panic disorder: tricyclics, MAOIs, high-potency benzodiazepines, and SSRIs. As with the treatment of depression and PTSD, SSRIs have become the treatment of choice for PTSD with panic disorder, because they have less serious side effects than the other classes of medication and are easier to administer (81). If the panic attacks do not respond to treatment with an SSRI, the clinician can consider an alternative antidepressant or augmentation with a high-potency long-acting benzodiazepine, such as clonazepam. Also, patients with both PTSD and panic disorder frequently have arousal symptoms that do not fully respond to the primary pharmacologic treatment. Augmentation with an adrenergic-inhibiting agent can be effective in these instances.

A person with PTSD has a lifetime risk of developing social phobia that is about three times that in the general population (10). Social phobia is especially prevalent among Vietnam veterans with PTSD; one study revealed a rate of 72 percent (82). This high rate is thought to be associated with shame and guilt due to lack of social support at homecoming and to feelings of stigmatization. Although these issues are best treated with psychotherapy, medications have proven to be helpful for social phobia. MAOIs and β-adrenergic blockers were among the first medications found to be helpful.

In recent years, a growing body of literature, including eight randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials that enrolled a total of 1,293 patients, has demonstrated the efficacy of SSRIs in the treatment of social phobia (83). Twice the number of patients responded to an SSRI as to placebo. When the change in mean Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale scores among patients who were treated with the drug were compared with those of patients who received placebo, the effect size was large in four trials, moderate in a second trial, and small in the other two trials. The SSRIs are the drug treatment of choice for PTSD concurrent with social phobia because of their dual effectiveness and tolerability. In selected instances in which a β-adrenergic blocker or an MAOI is chosen to treat PTSD symptoms, these agents may also serve the dual function of treating a coexisting social phobia.

Less evidence exists of the risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder co-occurring with PTSD. The NCS did not include obsessive-compulsive disorder among the disorders to study as co-occurring with PTSD. The NVVRS found a statistically significant increase in the prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder among male Vietnam veterans with PTSD. This finding is consistent with clinical observations of treatment-seeking Vietnam veterans. Persistent intrusive trauma-related memories can take on an obsessive quality. Compulsive behaviors are most frequently related to checking to ensure safety rather than trying to avoid or remove contamination. These symptoms can be moderated by medication treatment. The tricyclic clomipramine has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder but has not been studied for treatment of PTSD. SSRIs are currently the most commonly prescribed agents for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Multiple controlled trials have shown that they are as effective as clomipramine and have less adverse side effects (84). The co-occurrence of PTSD and obsessive-compulsive disorder is a strong indication for prescribing an SSRI.

Substance use disorders. The prevalence of substance use disorders concurrent with PTSD is high. The NCS demonstrated a lifetime risk of alcohol abuse or dependence of 51.9 percent among men and 27.9 percent among women with PTSD and of 34.5 percent among men and 26.9 percent among women with drug abuse and dependence (10). There is a high prevalence of PTSD among patients who are in methadone treatment. Evidence exists that substance abuse may follow the development of PTSD in many cases. A five-year prospective study conducted by Chilcoat and Breslau (85) revealed that young adults were 4.5 times as likely to develop a substance use disorder after the onset of PTSD as were youths who suffered trauma without developing PTSD. This finding supports the idea that, for many people, substance use may be a way of coping with PTSD. Patients with PTSD have more difficulty reducing alcohol intake and are more likely to experience relapse (86). Patients with PTSD who are in methadone treatment also have more difficulty adhering and responding to treatment. These observations suggest that successful treatment of PTSD is needed to improve the likelihood of achieving and maintaining abstinence.

Patients with PTSD have difficulty tolerating the increased affect associated with exposure therapies during the first months of recovery from substance abuse. Specialized treatment programs for persons with a diagnosis of both PTSD and substance abuse emphasize phase-oriented, cognitive-behavioral treatment to foster recovery from substance use while providing medication and skills training to cope with insomnia, nightmares, anxiety, and affect dysregulation. Benzodiazepines should be avoided because of the risk of dependency. Trazodone is often used to treat the commonly occurring sleep disturbances. Adrenergic-inhibiting agents can be useful in reducing the arousal symptoms of PTSD as well as nightmares. Buspirone can help reduce symptoms of generalized anxiety. Naltrexone is used for the treatment of alcohol dependence and has FDA approval for this indication. Reports of naltrexone being prescribed for PTSD have involved patients without comorbid alcohol dependence. PTSD symptoms did not significantly improve. Brady and associates (87) conducted an open clinical trial of sertraline among nine patients with comorbid PTSD and alcohol dependence. Over the course of 12 weeks significant decreases in PTSD symptoms, depression, and consumption of alcohol were noted. This study offers promise for more effective pharmacologic treatment for this challenging comorbid condition.

Psychosis. Patients with major psychotic disorders are at increased risk of PTSD. Rosenberg and colleagues (88), in a literature review of PTSD in populations of persons with serious mental illness, note that approximately 90 percent have been exposed to a traumatic event. This proportion compares with 56 percent exposed to trauma in a representative national sample of the general population (10). Childhood sexual and physical abuse, which carry significant risk factors for PTSD, have been reported among 34 to 53 percent of persons with serious mental illness (88). Current estimates of PTSD co-occurring among persons with serious mental illness range from 29 percent to 43 percent (88). Despite this high prevalence, PTSD can be infrequently diagnosed in this population (89). Some success has been reported in open clinical trials using cognitive-behavioral treatments with seriously mentally ill victims of sexual trauma (90). No studies have been reported of pharmacologic treatments for PTSD co-occurring with serious mental illness. In addition to antipsychotics, medications that have proven efficacy in the treatment of PTSD, such as SSRIs, may be helpful for this patient population.

Psychotic symptoms among persons with PTSD are more common than is generally recognized. Most of the studies that examined the presence of psychotic symptoms with PTSD were conducted among combat veterans. David and colleagues (91) screened 53 consecutively admitted combat veterans with PTSD for psychotic symptoms. Forty percent of the veterans reported at least one psychotic symptom during the preceding six months. Patients with psychotic symptoms have more severe PTSD symptoms, and there is a significant correlation with co-occurring major depressive disorder (92). The content of psychotic symptoms associated with PTSD is most often related to the traumatic event and is usually not bizarre. Auditory hallucinations are common, but visual hallucinations can also occur. In addition to perceptual disturbances, paranoid ideation is common, and delusions have been observed. A formal thought disorder is usually not part of the clinical presentation.

Studies of the effect of pharmacologic treatment on comorbid psychotic symptoms among patients with PTSD have been limited. Mueser and Butler (93) reported that auditory hallucinations among patients with PTSD were unresponsive to antipsychotic medication. In contrast, in an open clinical trial by Petty and colleagues (67) among 48 patients with PTSD, olanzapine was associated with reduced psychotic symptoms as measured by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Also, as previously described, a double-blind placebo controlled risperidone study showed a significant but modest reduction in PANSS scores among combat veterans with PTSD (66). It is becoming a more common practice for PTSD specialists to prescribe one of the atypical antipsychotics to treat associated psychotic symptoms. Randomized controlled clinical studies are needed to clarify the validity of this practice.

Sudden escalation to anger and impulsive aggression. A number of studies have demonstrated an increased prevalence of anger and aggression among persons with PTSD (94). These behaviors have been most studied among male combat veterans but have also been identified in other populations of trauma victims. The occurrence of anger and aggression among persons with PTSD can result in serious social consequences, such as damage to relationships, loss of work, and legal difficulties. People who experience anger and aggression as ego-alien commonly adapt a pattern of social avoidance to minimize the possibility that these symptoms will occur. Anger management classes with a cognitive-behavioral emphasis are a popular treatment modality in programs that specialize in PTSD treatment (95).

Pharmacologic treatment strategies to contain sudden escalation to anger and violence among patients with PTSD are based on neurochemical, physiologic, and clinical observations. Low levels of central nervous system 5-HIAA are associated with impulsive aggressive and self-destructive behavior (17). The serotonin-enhancing SSRIs have proven to be helpful in reducing irritability and aggressive behavior (96). The mood stabilizers lithium (97), carbamazepine (98), and valproate (99) have the ability to reduce affective lability and have been found to be effective in reducing aggressive behavior. Forster and colleagues (62) reported that lithium reduced irritability and angry outbursts among combat veterans with PTSD. In an open clinical trial, carbamazepine significantly reduced angry outbursts and violent behavior among combat veterans with PTSD (100). Valproate was especially effective in reducing arousal symptoms of PTSD in an open clinical trial (56). Mood stabilizers are usually used when serotonin-enhancing agents have not been effective.

Aggressive behavior is associated with hyperarousal. Adrenergic-inhibiting agents can target hyperarousal symptoms and may be effective in moderating irritability and aggressive behavior (98). Antipsychotic drugs are also effective for reducing aggressive behavior and are an alternative approach to the use of mood stabilizers and antiadrenergic agents. The emergence of atypical antipsychotics, with their reduced risk of adverse side effects, has encouraged clinicians to make more frequent use of antipsychotics for this indication.

Conclusions

In recent years, the understanding of the physiologic changes associated with PTSD has undergone rapid growth. This body of work has served as a foundation for identifying pharmacologic agents that have promise for moderating PTSD symptoms. SSRIs have been the most intensively studied class of drug for PTSD. On the basis of large multisite controlled clinical trials, SSRIs have become the medication of first choice for the treatment of PTSD. Other classes of pharmacologic agents hold promise for relieving PTSD symptoms. Antiadrenergic agents may prove to be effective in countering the adrenergic hyperactivity found among persons with PTSD. They may be especially useful in the early stages of treatment if they prove to inhibit the consolidation of PTSD symptoms and thus reduce chronicity. Mood stabilizers may have a role in reducing the sensitization of the limbic system that is thought to occur during the first weeks and months after exposure to a traumatic event. These agents also appear to be helpful in cases of chronic PTSD in which mood lability and impulsive aggressive behavior are problems.

The introduction of atypical antipsychotics offers a safer alternative to traditional antipsychotic agents for treating the more seriously troubled patients with PTSD whose illness does not respond well to first-line treatments. PTSD is often a chronic disorder and frequently co-occurs with other psychiatric disorders. Although treatment of PTSD must take these comorbid diagnoses into account, there is currently very little evidence-based information to guide clinicians. This will be an important area of inquiry for treatment studies of PTSD in the future.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the University of California, San Francisco, and the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Francisco. Send correspondence to Dr. Schoenfeld at DVA Medical Center (116P), 4150 Clement Street, San Francisco, California 94121 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Dosage recommendations and common side effects and risks of drugs used to treat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

1. Cannon W: The Wisdom of the Body. New York, Norton, 1936Google Scholar

2. Brunet A, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, et al: The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory: a proposed measure for PTSD criterion A2. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1480–1485, 2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine 346:982–987, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Marmar CR: The Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire in Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD, 2nd ed. Edited by Wilson JP, Keane T. New York, Guilford, 2003, in pressGoogle Scholar

5. Southwick S, Paige S, Morgan C, et al: Neurotransmitter alterations in PTSD: catecholamines and serotonin. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry 4:242–248, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wang S, Mason J, Southwick S, et al: Relationships between thyroid hormones and symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine 57:398–402, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Baker DG, West SA, Nicholson WE, et al: Serial CSF corticotropin-releasing hormone levels and adrenocortical activity in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:585–588, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Yehuda R, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, et al: Enhanced suppression of cortisol following dexamethasone administration in posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:83–86, 1993Link, Google Scholar

9. Orr SP, Metzger LJ, Lasko NB, et al: De novo conditioning in trauma-exposed individuals with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 109:290–298, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1048–1060, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. New Jersey, Lawrence Earlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

12. Frank JB, Kosten T, Giller EL Jr, et al: A randomized clinical trial of phenylzine and imipramine for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:1289–1291, 1988Link, Google Scholar

13. Davidson JR, Kudler HS, Smith R, et al: Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder with amitriptyline and placebo. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:259–266, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Reist C, Kauffmann CD, Haier RJ, et al: A controlled trial of desipramine in 18 men with posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:513–516, 1989Link, Google Scholar

15. Southwick SM, Yehuda R, Giller E, et al: Use of tricyclics and monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the treatment of post traumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review, in Catecholamine Function in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Emerging Concepts. Edited by Murburg MM. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

16. Neal LA, Shapland W, Fox C: An open trial of moclobemide in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 12:231–237, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Placidi GP, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, et al: Aggressivity, suicide attempts, and depression: relationship to cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite levels. Biological Psychiatry 50:783–791, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Goddard AW, Woods SW, Sholomskas DE, et al: Effects of the serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluvoxamine on yohimbine-induced anxiety in panic disorder. Psychiatry Research 48:119–133, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Brady K, Pearlstein T, Asnis GM, et al: Efficacy and safety of sertraline treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283:1837–1844, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Davidson JR, Rothbaum BO, van der Kolk BA, et al: Multicenter, double-blind comparison of sertraline and placebo in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:485–492, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Zohar J, Amital D, Miodownik C, et al: Double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of sertraline in military veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 22:190–195, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Marshall RD, Beebe KL, Oldham M, et al: Efficacy and safety of paroxetine treatment for chronic PTSD: a fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1982–1988, 2001Link, Google Scholar

23. Van der Kolk BA, Dreyfuss D, Michaels M, et al: Fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55:517–522, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

24. Marmar CR, Schoenfeld FB, Weiss DS, et al: Open trial of fluvoxamine treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 8):66–72, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

25. Seedat S, Stein, DJ, Ziervogel C, et al: Comparison of response to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in children, adolescents, and adults with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 12:37–46, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Londborg PD, Hegel MT, Goldstein S, et al: Sertraline treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: results of 24 weeks of open-label continuation treatments. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62:325–331, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Davidson J, Pearlstein T, Londborg P, et al: Efficacy of sertraline in preventing relapse of posttraumatic stress disorder: results of a 28-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1974–1981, 2001Link, Google Scholar

28. Gregorian RS, Golden KA, Bache A, et al: Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 36:1577–1589, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Hidalgo R, Hertzberg MA, Mellman T, et al: Nefazodone in post-traumatic stress disorder: results from six open-label trials. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 14:61–68, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Mellman TA, David D, Barza L: Nefazodone treatment and dream reports in chronic PTSD. Depression and Anxiety 9:146–148, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Hertzberg MA, Feldman ME, Beckham JC, et al: Trial of trazodone for posttraumatic stress disorder using a multiple baseline group design. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 16:294–298, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Smajkic A, Weine S, Duric-Bijedic Z, et al: Sertraline, paroxetine, and venlafaxine in refugee posttraumatic stress disorder with depression symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress 14:445–452, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Davidson JR, Weisler RH, Butterfield MI, et al: Mirtazapine vs placebo in posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot trial. Biological Psychiatry 53:188–191, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Canive JM, Clark RD, Calais LA, et al: Bupropion treatment in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: an open study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 18:379–383, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Yehuda R, Siever L, Teicher MH, et al: Plasma norepinephrine and 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol concentrations and severity of depression in combat posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder. Biological Psychiatry 44:970–975, 1998Google Scholar

36. Pitman RK: Post-traumatic stress disorder, hormones, and memory. Biological Psychiatry 26:221–223, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Cahill L, Prins B, Weber M, et al: Beta-adrenergic activation and memory for emotional events. Nature 371:702–704, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Pitman RK, Sanders KM, Zusman RM, et al: Pilot study of secondary prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder with propranolol. Biological Psychiatry 51:189–192, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Vaiva G, Docrocq F, Jezequel K, et al: Immediate treatment with proparanolol decreases posttraumatic stress disorder two months after trauma. Biological Psychiatry 54:947–949, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Famularo R, Kinscherff R, Fenton T: Propranolol treatment for childhood posttraumatic stress disorder, acute type: a pilot study. American Journal of Diseases of Children 142:1244–1247, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Kolb LC, Burris BC, Griffiths S: Propranolol and clonidine in the treatment of the chronic post traumatic stress disorders of war, in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Psychological and Biological Sequelae. Edited by van der Kolk BA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1984Google Scholar

42. Kinzie JD: Therapeutic approaches to traumatized Cambodian refugees. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2:75–91, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Kaplan HI, Sadock B: Synopsis of Psychiatry, 8th ed. Baltimore, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1998Google Scholar

44. Harmon RJ, Riggs P: Clonidine for posttraumatic stress disorder in preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:1247–1249, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Kinzie JD, Leung P: Clonidine in Cambodian patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:546–550, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Horrigan JP, Barnhill LJ: The suppression of nightmares with guanfacine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:371, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

47. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Kanter ED, et al: Reduction of nightmares and other PTSD symptoms in combat veterans by prazosin: a placebo controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:371–373, 2003Link, Google Scholar

48. Gelpin E, Bonne O, Peri T, et al: Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: a prospective study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:390–394, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

49. Braun P, Greenberg D, Dasberg H, et al: Core symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder unimproved by alprazolam treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51:236–238, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

50. Risse SC, Whitters A, Burke J, et al: Severe withdrawal symptoms after discontinuation of alprazolam in eight patients with combat-induced posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51:206–209, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

51. Duffy JD, Malloy PF: Efficacy of buspirone in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: an open trial. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 6:33–37, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Grillon C, Morgan CA, Southwick SM, et al: Baseline startle amplitude and prepulse inhibition in Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Research 64:169–178, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Lipper S, Davidson JR, Grady TA, et al: Preliminary study of carbamazepine in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychosomatics 27:849–854, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Friedman LM: Valproate and carbamazepine in the treatment of panic and posttraumatic stress disorders, withdrawal states, and behavioral dyscontrol syndromes. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 12:36S-41S, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Looff D, Grimley P, Kuller F, et al: Carbamazepine for PTSD (letter). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:703–704, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Fesler FA: Valproate in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 52:361–364, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

57. Berlant J, van Kammen DP: Open-label topiramate as primary or adjunctive therapy in chronic civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:15–20, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Hertzberg MA, Butterfield MI, Feldman ME, et al: A preliminary study of lamotrigine for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry 45:1226–1229, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Hamner MB, Brodrick PS, Labbate LA: Gabapentin in PTSD: a retrospective, clinical series of adjunctive therapy. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 13:141–146, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Van der Kolk BA: Psychopharmacological issues in posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:1086–1087, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

61. Kitchner I, Greenstein R: Low-dose lithium carbonate in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:683–691, 1983Abstract, Google Scholar

62. Forster PL, Schoenfeld FB, Marmar CR, et al: Lithium for irritability in post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 8:143–149, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Leyba CM: Risperidone in PTSD. Psychiatric Services 49:245–246, 1998Link, Google Scholar

64. Krashin D, Oates EW: Risperidone as an adjunct therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. Military Medicine 164:605–606, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Monnelly EP, Ciraulo DA, Knapp C, et al: Low-dose risperidone as adjunctive therapy for irritable aggression in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 23:193–196, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Hamner MB, Faldowski RA, Ulmer HG, et al: Adjunctive risperidone treatment in post-traumatic stress disorder: a preliminary controlled trial of effects on comorbid psychotic symptoms. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 18:1–8, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Petty F, Brannan S, Casada J, et al: Olanzapine treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder: an open-label study. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 16:331–337, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Butterfield MI, Becker ME, Connor KM, et al: Olanzapine in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 16:197–203, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Stein MB, Kline NA, Matloff JL: Adjunctive olanzapine for SSRI-resistant combat-related PTSD: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1777–1779, 2002Link, Google Scholar

70. Sokolski KN, Denson TF, Lee RT, et al: Quetiapine for treatment of refractory symptoms of combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Military Medicine 168:486–489, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Hamner MB, Deitsch SE, Brodrick PS, et al: Quetiapine treatment in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: an open adjunctive therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 23:15–20, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, et al: Trauma and the Vietnam War Generation: Report of the Findings From the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1990Google Scholar

73. Foa EB, Davidson JR, Frances A (eds): The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 16):1–76, 1999Google Scholar

74. Brady KT, Killeen TK, Brewerton T, et al: Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:22–32, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75. Shalev AY, Freedman S, Peri T, et al: Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:630–637, 1998Link, Google Scholar

76. Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, et al: Psychiatric sequelae of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:81–87, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77. Keane TM, Taylor KL, Penk WE: Differentiating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from major depression (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Journal of Anxiety Disorders 11:317–328, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD: Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68:748–766, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79. McFarlane AC: Posttraumatic stress disorder: a model of the longitudinal course and the role of risk factors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(suppl 5):21–23, 2000Google Scholar

80. Michelson L, June K, Vives A, et al: The role of trauma and dissociation in cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy outcome and maintenance for panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behavior Research and Therapy 36:1011–1050, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81. Sheehan D: Current concepts in the treatment of panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:16–21, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

82. Orsillo SM, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, et al: Social phobia and PTSD in Vietnam Veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress 9:235–252, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Van der Linden GL, Stein DJ, van Balkom AJ: The efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for social anxiety disorder (social phobia): a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 15:S15-S23, 2000Google Scholar

84. Pigott TA, Seay MD: A review of the efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:101–106, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

85. Chilcoat HD, Breslau N: Posttraumatic stress disorder and drug disorders: testing causal pathways. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:913–917, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

86. Brown PJ, Stout RL, Mueller T: Posttraumatic stress disorder in substance abuse relapse among women: a pilot study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 10:124–128, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

87. Brady KT, Sonne SC, Roberts JM: Sertraline treatment of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56:502–505, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

88. Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT, Friedman MJ, et al: Developing effective treatments for posttraumatic stress disorders among people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:1453–1461, 2001Link, Google Scholar

89. Mueser K, Trumbetta S, Rosenberg S: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:493–499, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

90. Harris M: Treating sexual abuse trauma with dually diagnosed women. Community Mental Health Journal 32:371–385, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

91. David D, Kutcher G, Jackson EI: Psychotic symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:29–32, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

92. Hamner MB, Frueh C, Ulmer H, et al: Psychotic features and illness severity in combat veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry 45:846–852, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

93. Meuser KT, Butler RW: Auditory hallucinations in combat-related chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:299–302, 1987Link, Google Scholar

94. Yehuda R: Managing anger and aggression in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:33–37, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

95. Reilly PM, Shopshire MS: Anger management group treatment for cocaine dependence: preliminary outcomes. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 26:161–177, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

96. Coccaro E, Astill J, Herbert J, et al: Fluoxetine treatment of impulsive aggression in DSM-III-R personality disorder patients. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 10:373–375, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

97. Shader RI, Jackson AH, Dodes LM: The antiaggressive effects of lithium in man. Psychopharmacologia 40:17–24, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

98. Mattes JA, Rosenberg J, Mays D: Carbamazepine versus propranolol in patients with uncontrolled rage outbursts: a random assignment study. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 20:98–100, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

99. Donovan SJ, Stewart JW, Nunes EV, et al: Divalproex treatment for youth with explosive temper and mood lability: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:118–120, 2000Link, Google Scholar

100. Wolf ME, Alavi A, Mosnaim AD: Posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans clinical and EEG findings: possible therapeutic effects of carbamazepine. Biological Psychiatry 23:642–644, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar