Lack of Relationship Between Long-Term Use of Benzodiazepines and Escalation to High Dosages

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The objective of this study was to determine whether long-term benzodiazepine use is associated with dose escalation. METHODS: The authors examined changes in dose and the frequency of dose escalation among new and continuing (at least two years) recipients of benzodiazepines identified from a database containing drug-dispensing and health care use data for all New Jersey Medicaid patients for 39 months. Independent variables included age; Medicaid eligibility category; gender; race or ethnicity; neighborhood socioeconomic variables; chronic illnesses, such as schizophrenia, bipolar illness, panic disorder, and seizure disorder; and predominant benzodiazepine received. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine the association between the independent variables and escalation to a high dosage (at least 20 diazepam milligram equivalents [DMEs] per day for elderly patients and at least 40 DMEs per day for younger patients). RESULTS: A total of 2,440 patients were identified, comprising 460 new and 1,980 continuing recipients. Seventy-one percent of continuing recipients had a permanent disability. Among all groups of continuing recipients, the median daily dosage remained constant at 10 DMEs during two years of continuous use. No clinically or statistically significant changes in dosage were observed over time. The incidence of escalation to a high dosage was 1.6 percent. Subgroups with a higher risk of dose escalation included antidepressant recipients and patients who filled duplicate prescriptions for benzodiazepines at different pharmacies within seven days. Elderly and disabled persons had a lower risk of dose escalation than younger patients. CONCLUSION: The results of this study did not support the hypothesis that long-term use of benzodiazepines frequently results in notable dose escalation.

Several decades after their introduction to the market, benzodiazepines are still among the most widely prescribed drugs in the world (1) and represent highly effective treatments for anxiety, panic disorder, bipolar illness, and sleep and seizure disorders (2,3,4,5). Although benzodiazepines are less toxic than the older sedative-hypnotic agents that they replaced, they also can produce a range of side effects, including excessive sedation, possibly leading to falls and hip fractures, and physiological dependence (2).

A controversial and relatively unstudied issue is the relationship between long-term therapeutic use of benzodiazepines and abuse. Although guidelines rarely recommend use of benzodiazepines for more than four months (6), long-term use may be warranted in some situations. For example, long-term use of benzodiazepines may improve outcomes among patients with panic disorder (4,7). Popular beliefs and the media tend to promote an image of the long-term benzodiazepine recipient as an "addict who has lost control over the drug" (8). However, the evidence suggests that abuse of benzodiazepines is more likely associated with concurrent or previous abuse of other drugs, such as alcohol, opiates, or illegal substances (2,9), rather than long-term use per se.

Nevertheless, a recent comprehensive review suggested that even a history of substance abuse does not preclude judicious use of benzodiazepines (9). Approximately 8 percent of U.S. adults receive at least one benzodiazepine prescription a year (3); of these, approximately 15 to 25 percent take these drugs for at least a year (3,10). Long-term use of benzodiazepines may result in physiological dependence that, in some cases, requires tapered discontinuation of the drug. Some long-term benzodiazepine recipients who are still anxious or who still experience panic attacks may need additional therapy during or after discontinuation of benzodiazepine use (11,12).

Hardly any population-based data exist on changes in dosages over time among long-term therapeutic users of benzodiazepines and the frequency of dose escalation to levels indicating possible dependence. In a cohort study of 862 outpatient benzodiazepine recipients at a Japanese teaching hospital, 7.9 percent were prescribed these agents for at least three years (13). The average dosage remained stable at approximately 8.5 diazepam milligram equivalents (DMEs) per day. Similarly, several small studies in the United States with sample sizes of up to 60 found stable or declining dosages of benzodiazepines among patients treated for panic disorder for one year (14,15,16). However, no study has estimated the proportion of long-term therapeutic users of benzodiazepines whose dosages subsequently escalated to high, problematic levels in large community populations.

In this study, we examined changes in dosage and the frequency of dose escalation among patients in a statewide Medicaid population who received benzodiazepines for at least two years. We focused on the majority of patients who were initially prescribed appropriate dosages of benzodiazepines in order to provide clinicians with a more realistic estimate of the probability that long-term therapeutic use would lead to very high dosages indicative of potential dependency. In addition, we identified patient characteristics associated with risk of dose escalation over two years of continuous use.

Methods

Study design

We used a retrospective cohort design to identify long-term recipients of benzodiazepines whose initial dosages were in therapeutic ranges in order to determine the frequency and predictors of escalation to a high dosage. We identified both incident (new) and continuing users of benzodiazepines from a database containing drug-dispensing and health care use data for all New Jersey Medicaid patients from October 1987 to December 1990, a control population in an unrelated study (17). Medicaid data represent one of the few reliable sources of population-based longitudinal data on medication use.

Cohort definitions

We included patients in three Medicaid eligibility categories: Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC), which enrolled mainly low-income women with children; Old Age Assistance (OAA), which enrolled elderly persons who are receiving supplemental security income; and Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled (APTD), which enrolled persons with permanent physical or mental disabilities. To control for changes in enrollment or case mix over time (18,19,20,21), we identified cohort members who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid (at least ten months in every 12-month period) throughout the three-year observation period.

We defined long-term use of benzodiazepines as an uninterrupted episode of benzodiazepine use of at least two years during the period January 1988 to December 1990. Episodes were defined as a chronological sequence of benzodiazepine dispensings with breaks of up to 61 days between any two dispensings. Because 30-day supplies of benzodiazepines are commonly prescribed, the duration of each benzodiazepine episode was determined to be 30 days beyond the date of the last prescription in a sequence.

Because it was impossible to know the circumstances that led to benzodiazepine use among patients who were already receiving benzodiazepines at the start of the observation period, we defined an incident cohort of benzodiazepine recipients who did not receive any benzodiazepine prescriptions (generally a 30-day supply) during a baseline period from October 1987 to December 1987 but who initiated an episode of long-term use after that. We defined long-term (continuing) recipients as those who received one or more prescriptions for benzodiazepines during this three-month baseline observation period and who continued to receive benzodiazepines for a minimum of two years.

Data sources

Data were extracted from monthly enrollment records and drug and medical care claims files in the computerized New Jersey Medicaid management information systems. Demographic data extracted from enrollment files included age, gender, race (white, black, Hispanic, or other), eligibility category, and zip code of residence. Medication claims data on all prescriptions filled by enrollees included patient identifier, date and location of dispensing, national drug code, and number of units dispensed—for example, the number of tablets. In addition, to identify patients with specific chronic illnesses that frequently require treatment with benzodiazepines, we obtained inpatient and outpatient ICD-9-CM diagnoses associated with health care claims during the first year of observation. Medicaid prescribing data are highly reliable and valid, yielding measures of medication use that are internally consistent and stable over time (18,19,20,21,22,23).

Measures of dose and dose escalation

We defined DME dosages for each benzodiazepine generic entity, which allowed us to convert dosages for all benzodiazepines dispensed to therapeutically equivalent DME dosages. We used the equivalencies proposed by Shader and colleagues (24), which we recently validated. The relative potencies of equivalent dosages of various benzodiazepines are diazepam, 1.00; alprazolam, 10.00; chlordiazepoxide, .20; clonazepam, 20.00; chlorazepate, .67; estazolam, 1.43; flurazepam, .33; halazepam, .17; lorazepam, 6.67; oxazepam, .33; prazepam, .50; quazepam, .67; temazepam, .33; and triazolam, 40.00. (17). To further increase the reliability of measures of daily dosage for each patient, we aggregated all prescriptions within an episode into six-month periods and computed the average daily dosage, in DMEs, for each patient in each of four six-month periods.

Dose escalation was determined by estimating linear time trends in monthly median benzodiazepine dosage after a three-month initiation period. We defined a secondary measure of dose escalation as increasing from initial dosages in recommended dosage ranges of less than ten DMEs for elderly patients and less than 20 DMEs for younger patients to high dosages during the last six-month period during two years of continuous use (17,25,26). High daily dosage was defined by an expert panel, including two academic psychopharmacologists, as at least 20 DMEs per day for patients aged 65 years and over and at least 40 DMEs per day for younger patients (25,26). Very high dosage was defined for all patients as at least 100 DMEs.

Independent variables

We analyzed several independent variables considered to be potential predictors of escalation to a high dosage. These variables included demographic variables, such as age (younger than 45 years, 45 to 64 years, and 65 years or older), Medicaid enrollment category, gender, and race or ethnicity as well as neighborhood socioeconomic variables based on zip code, including urban location (defined as a zip code that is 100 percent urban) and density of poverty (defined as living in a zip code in which at least 5 percent of households have an income below $15,000). In addition, we identified patients who had known chronic mental illnesses—schizophrenia, bipolar illness, depression, panic disorder, or seizure disorder—on the basis of one inpatient or two outpatient ICD-9-CM diagnosis for these conditions during the base year, an algorithm that has been shown to have high specificity and moderate sensitivity in previous research (20).

We identified the predominant type of benzodiazepine received during the observation period on the basis of the number of dispensings. We hypothesized that short-half-life, high-potency drugs—for example, lorazepam, alprazolam, and triazolam—would be associated with a greater risk of dose escalation on the basis of previous reports suggesting that these drugs produce more withdrawal symptoms (7). We also constructed several variables indicative of baseline use of other drugs that pose risks of habituation—barbiturates, nonbarbiturate sedatives-hypnotics, and narcotic analgesics—as well as other drug classes that are not associated with habituation risks but that are associated with benzodiazepine use, such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, and buspirone. In addition, we constructed a "pharmacy hopping" variable as a measure of possible benzodiazepine abuse and diversion, defined as filling a prescription for the same benzodiazepine in two different pharmacies within seven days.

Statistical analysis

After identifying the cohorts of long-term benzodiazepine recipients, we plotted the trends in median daily benzodiazepine dosage (and interquartile ranges) for each six-month period, stratified by the incident cohort of new recipients and the cohort of continuing recipients. We also fit a regression to the trend in monthly median dosages to determine the size and significance of any trend in benzodiazepine dosage, controlling for first-order autocorrelation (20,27,28). We also repeated the above analyses of trends in benzodiazepine dosage in cohorts with 18 months of continuous use to determine the sensitivity of the results to a different definition of long-term use. However, the results were almost identical to those reported above and therefore are not presented here.

Next, we computed the frequency and percentage of escalation to high dosage. Finally, we conducted logistic regression analyses to determine the association between the above independent variables and escalation to a high dosage (the dependent variable). We initially included all variables in the logistic model that were associated with dose escalation in univariate models at a significance level of p<.10. In the final model, we retained all variables for which p<.05.

Results

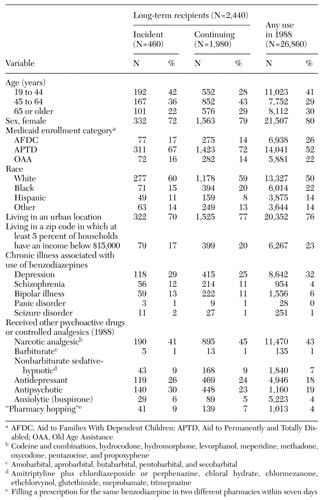

Among 26,860 continuously enrolled patients who received benzodiazepines at any time in 1988, 3.2 percent received a high dosage and 14.4 percent received these medications for at least two years without interruption. Within this group of long-term recipients, we identified 2,440 recipients who met the study entry criteria, comprising 460 incident (new) recipients and 1,980 continuing recipients. The characteristics of these two groups are summarized in Table 1. Seventy-one percent of long-term benzodiazepine recipients were eligible for Medicaid through APTD, a category requiring a permanent medical or psychiatric illness serious enough to prevent any employment. A majority of patients were female and a majority were white, although more than a quarter were black or Hispanic. At least a quarter of the patients had a diagnosis for a chronic illness for which benzodiazepines are often prescribed—for example, schizophrenia or depression. More than 40 percent of long-term benzodiazepine recipients also received one or more prescriptions for a narcotic analgesic in the base year. About a quarter were treated with an antidepressant agent, and another quarter received an antipsychotic agent.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of long-term benzodiazepine recipients were similar to those of benzodiazepine recipients in general, except that the long-term recipients were more likely to be middle aged, to have a permanent disability, or to be undergoing treatment for depression or schizophrenia (Table 1).

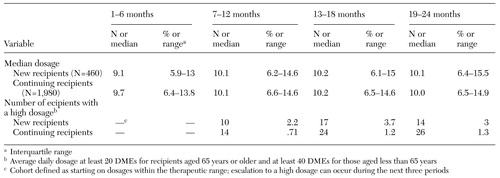

Table 2 presents trends in median daily benzodiazepine dosage (and interquartile ranges) during two years of continuous use in the cohorts of new and continuing benzodiazepine recipients. After a small increase during the first period of use—presumably to titrate dosages—median daily dosage levels remained constant at about ten DMEs for the duration of these long-term benzodiazepine episodes, well within recommended dosage ranges established by the expert panel. No clinically or statistically significant changes were observed over time in either the median dosage or the interquartile range (Table 2).

The incidence of escalation to high dosages during the two years of continuous use was relatively small, occurring among 40 (1.6 percent) of 2,440 patients. Among the 460 new recipients, 14 (3 percent) experienced escalation to a high dosage, whereas among the 1,980 continuing recipients, only 26 (1.3 percent) showed evidence of dose escalation (Table 2). None of the new or continuing recipients experienced escalation to very high dosages of 100 DMEs or more.

Patients with indications of substance abuse were somewhat more likely to experience benzodiazepine dose escalation. For example, eight (16.7 percent) of the 48 "pharmacy hoppers" in 1990 and eight (4 percent) of the 190 narcotic analgesic recipients in the incident cohort experienced dose escalation.

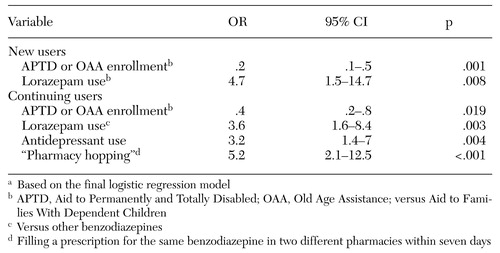

The results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis are presented in Table 3. Only a few variables were significant predictors of dose escalation. Regular use of the short-acting, high-potency benzodiazepine lorazepam was associated with dose escalation among both new and continuing benzodiazepine recipients. Elderly and disabled persons were significantly less likely to experience dose escalation than younger patients, both for new and continuing recipients. In addition, among continuing recipients only, use of antidepressants and evidence of "pharmacy hopping" were both associated with escalation to high benzodiazepine dosage. The odds of dose escalation among "pharmacy hoppers" versus other long-term recipients was 5.2 (95 percent CI=2.1 to 12.5).

Discussion

It has been well established that a significant minority of benzodiazepine recipients continue benzodiazepine therapy for long periods. In 1990, up to 25 percent of benzodiazepine recipients used these drugs regularly for at least one year (10). A controversy exists among clinicians, the general public, and regulatory agencies about the likelihood that long-term use of benzodiazepines will lead to inappropriate drug-taking behavior, such as escalation to high benzodiazepine dosages.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration drug labeling currently discourages long-term use of benzodiazepines (defined as four months or more). The wide gulf in medical opinion about benzodiazepines is exemplified by divergent conclusions in the published medical literature. For example, one U.K. psychopharmacologist concluded in a published 1999 review article that "benzodiazepines are now recognized as major drugs of abuse" (29). In contrast, in another widely referenced review article, a U.S. scientist asserted: "There is no evidence that physiological dependence on benzodiazepines is accompanied by inappropriate drug-taking behavior, e.g., escalation of doses" (30). Virtually no longitudinal patient-level data from large population-based samples exist to assess the hypothesis that long-term use leads to escalation to excessive dosage levels. Previous studies of small samples, often from a single clinic, generally challenged the notion that long-term therapeutic use of benzodiazepines has such consequences (13,14,15,16).

Using 39 months of computerized patient-level drug-dispensing data, we studied a large statewide sample of 2,440 Medicaid patients whose initial dosage levels were within recommended ranges but who subsequently received benzodiazepines continuously for at least two years. Consistent with the results of previous research (3,31), such long-term recipients were very likely to have chronic disabling conditions (71 percent), either physical or psychological. Among all groups of long-term recipients, no change in median dosage was observed over time. The overall incidence of escalation to a high dosage was less than 2 percent, and none of the long-term benzodiazepine recipients experienced escalation to a very high dosage of at least 100 DMEs.

Specific patient subgroups appear to have elevated odds of dose escalation: recipients of the high-potency benzodiazepine lorazepam, those who are using antidepressants, and patients who obtain duplicate prescriptions of benzodiazepines within a seven-day period. Elderly and disabled patients had a lower risk of dose escalation than younger patients. The overall pattern of results was very similar for new and continuing recipients. A major strength of this study was our ability to identify patients who were receiving usual dosages of benzodiazepines at the start of the two-year period of continuous use, thus providing a more valid estimate of the probability that long-term therapeutic use leads to notable dose escalation.

The relatively higher incidence of inappropriate dose escalation among patients who visited multiple pharmacies is consistent with previous research indicating that a proportion of persons who misuse benzodiazepines have substance dependence disorders (9,30). Our data were insufficient to adequately examine this possibility in detail. The association of lorazepam use with dose escalation may be related to the widespread use of lorazepam compared with other short-half-life, high-potency benzodiazepines.

This study had several additional limitations. First, we are uncertain about the generalizability of these findings from a low-income Medicaid population to other groups of long-term benzodiazepine recipients. However, our overall findings indicating little relationship between long-term benzodiazepine use and escalation to high dosages is similar to the findings of smaller-scale studies of higher-income populations (13,14,15,16).

Second, our primary endpoint was based on longitudinal patterns of receipt of dispensed medications, not actual ingestion of benzodiazepines. Many patients may not actually take the medications as prescribed by their physicians. However, the patients in this study continued to refill their monthly prescriptions over a period of at least two years. This continuing pattern of new and refill prescriptions makes such noncompliance less likely.

Third, our data set did not include other important predictors of potential benzodiazepine abuse, such as measures of illicit drug and alcohol use. However, the tiny number of patients experiencing escalation to a high dosage also reduces the practical importance of including all predictors of such infrequent escalation. Fourth, administrative data cannot identify whether appropriate indications existed for initiating therapy, even for serious mental illness, such as bipolar disorder. A final limitation is that our definition of escalation of dosage may, in some cases, result in false-positive identifications of problematic benzodiazepine use. Some patients may require above-average dosages for legitimate medical reasons, and in some cases lower dosages could represent problematic underuse (2).

Conclusions

This is the first large population-based study to estimate the incidence and predictors of escalation to a high dosage among long-term recipients of benzodiazepines. These longitudinal data on 2,440 long-term recipients of benzodiazepines suggest that the great majority of such patients have serious physical and mental illnesses and that long-term therapeutic use rarely results in escalation to a high dosage. Furthermore, the small number of patients who escalate to a high dosage are also more likely to exhibit characteristics of substance abuse, such as "pharmacy hopping." Although more research is needed on the outcomes of long-term use of benzodiazepines, these data provide some reassurance that most long-term recipients are unlikely to experience escalation in their dosage of benzodiazepines over time.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01-DA-10371 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

All authors except Dr. Salzman are affiliated with the department of ambulatory care and prevention of Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, 133 Brookline Avenue, Sixth Floor, Boston, Massachusetts 02215 (e-mail, [email protected]. edu). Dr. Simoni-Wastila is also with the department of pharmacy practice and science of the University of Maryland at Baltimore. Dr. Salzman is with the Massachusetts Mental Health Center in Boston.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of incident (new) and continuing recipients of benzodiazepines in a Medicaid cohort

|

Table 2. Changes in daily dosage of benzodiazepines in diazepam milligram equivalents (DMEs) during two years of continuous use

|

Table 3. Significant predictors of escalation to a high dosage among new and continuing recipients of benzodiazepinesa

a Based on the final logistic regression model

1. IMS America: IMS reports new products, patent expirations, and DTC advertising prompt shifts in 1997 US pharmaceutical ranking. Press release, available at http://ims-america/communications/pr_rank.html, Mar 12, 1998Google Scholar

2. Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ: Use of benzodiazepines in anxiety disorders. New England Journal of Medicine 328:1398–1405, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Woods JH, Winger G: Current benzodiazepine issues. Psychopharmacology 118:107–115, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Ballenger JC: Long-term pharmacologic treatment of panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 52(suppl 12):18–23, 1991Google Scholar

5. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 151(suppl 12):1–35, 1994Google Scholar

6. Carl Salzman (ed): Benzodiazepine Dependence, Toxicity, and Abuse: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

7. Uhlenhuth EH, Balter MB, Ban TA, et al: International study of expert judgment on therapeutic use of benzodiazepines and other psychotherapeutic medications: IV. therapeutic dose dependence and abuse liability of benzodiazepines in the long-term treatment of anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 19:23S-29S, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wright N, Caplan R, Payne S: Community survey of long-term daytime use of benzodiazepines. British Medical Journal 309:27–28, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Posternak MA, Mueller TI: Assessing the risks and benefits of benzodiazepines for anxiety disorders in patients with a history of substance abuse or dependence. American Journal of Addictions 10:48–68, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Balter MB: Prevalence of Medical Use of Prescription Drugs. Presented at the conference "NIDA Technical Review: Evaluation of the Impact of Prescription Drug Diversion Control Systems on Medical Practice and Patient Care: Possible Implications for Further Research." Bethesda, Md, May 30 to June 1, 1991Google Scholar

11. Salzman C: Addiction to benzodiazepines. Psychiatric Quarterly 69:251–261, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Spiegel DA: Psychological strategies for discontinuing benzodiazepine treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 19:17S-22S, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Ishigooka J, Sugiyama T, Suzuki M, et al: Survival analytic approach to long-term prescription of benzodiazepine hypnotics. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 52:541–545, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Davidson JR: Continuation treatment of panic disorder with high-potency benzodiazepines. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51 (suppl A):31–37, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

15. Pollack MH, Tesar GE, Rosenbaum JF, et al: Clonazepam in the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia: a one-year follow-up. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 6:302–304, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Sheehan DV: Benzodiazepines in panic disorder and agoraphobia. Journal of Affective Disorders 13:169–181, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ross-Degnan D, Simoni-Wastila L, Brown J, et al: A controlled study of the effects of state surveillance on volume and appropriateness of benzodiazepine prescribing in a Medicaid population. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, Boston, November 12–16, 2000, and the annual meeting of the Academy for Health Services Research and Health Policy, Atlanta, June 10–12, 2001Google Scholar

18. Soumerai SB, Avorn J, Ross-Degnan D, et al: Payment restrictions for prescription drugs under Medicaid: effects on therapy, cost, and equity. New England Journal of Medicine 317:550–556, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan DG, Avorn J, et al: Effects of Medicaid drug-payment limits on admission to hospitals and nursing homes. New England Journal of Medicine 325:1072–1077, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Ross-Degnan DG, et al: Effects of a limit on Medicaid drug-reimbursement benefits on the use of psychotropic agents and acute mental health services by patients with schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 331:650–655, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan DG, Gortmaker S, et al: Withdrawing payment for non-scientific drug therapy: intended and unexpected effects of a large scale natural experiment. JAMA 263:831–839, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Federspiel CF, Ray WA, Schaffner W: Medicaid records as a valid data source: the Tennessee experience. Medical Care 14:166–172, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. US Department of Commerce: Medicaid Data as a Source for Postmarketing Surveillance Information, vol 1, 1984. Prepared for the US Food and Drug Administration, contract 223–82–3021Google Scholar

24. Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ, Ciraulo DA: Treatment of dependence on barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and other sedative-hypnotics, in Manual of Psychiatric Therapeutics. Edited by Shader RI. Boston, Little Brown, 1994Google Scholar

25. Salzman C: Treatment of Anxiety in Clinical Geriatric Psychopharmacology. Edited by Salzman C. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1992Google Scholar

26. Sheikh JI, Salzman C: Anxiety in the elderly: course and treatment. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 18:871–883, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Gillings D, Makuc D, Siegel E: Analysis of interrupted time series mortality trends: an example to evaluate regionalized perinatal care. American Journal of Public Health 71:38–46, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, et al: Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 27:299–309, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Lader MH: Limitations on the use of benzodiazepines in anxiety and insomnia: are they justified? European Neuropsychopharmacology 9(suppl 6):S399-S405, 1999Google Scholar

30. Woods JH, Katz JL, Winger G: Use and abuse of benzodiazepines: issues relevant to prescribing. JAMA 260:3476–3480, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Mellinger GD, Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH: Prevalence and correlates of the long-term regular use of anxiolytics. JAMA 251:375–379, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar