Satisfaction of Inpatients and Outpatients With Staff, Environment, and Other Patients

Abstract

The study described here compared levels of satisfaction with staff, environment, and other patients among 420 first-time and long-term patients in psychiatric outpatient and inpatient settings. The demographic, clinical, and outcome variables associated with satisfaction were explored. Patient satisfaction was related to quality of life, social functioning, treatment expectations, and one-year psychological and physical prognoses. Perceptions of other patients were significantly more positive among long-term patients than among first-time patients. The concerns of first-time patients about other patients are of especial importance, and they should be addressed during initial treatment.

Patient satisfaction is an important aspect of service quality in determining treatment continuity and treatment outcome (1,2,3). However, no universal method of measuring patient satisfaction exists, which limits the possibility of comparing studies (2,3,4). Also, the underlying dimensions of patient satisfaction vary in different studies. For example, satisfaction with staff and with environment are often considered, but little is known about patients' attitudes toward fellow patients.

Most research on patient satisfaction has focused either on outpatient services (3,5) or on inpatient institutions (1,2,6). Controlled comparisons of patient satisfaction between settings have rarely been conducted. Also, no precise knowledge exists about the association between demographic variables and diagnosis and patient satisfaction (2,4,5). Although some studies suggest that satisfaction is influenced by patients' expectations, (3), other studies find that fulfillment of expectations may have little to do with expressed satisfaction (4). Further, the relationships between patient satisfaction and quality of life and insight into illness have not been fully explored (2,6).

This study examined whether levels of patient satisfaction vary by inpatient versus an outpatient setting and by first-time versus long-term treatment status. The associations between patient satisfaction and demographic variables, diagnosis, social functioning, quality of life, expectations, illness severity, and insight into illness were also examined.

Methods

The study was conducted in four community mental health centers and in two psychiatric hospital wards in Vienna, Austria, between January 1995 and April 1996. Patients not considered for inclusion in the study were those who had acute psychosis, mental retardation, or dementia; those who had brief crisis interventions, with immediate referrals to other institutions; those who lacked sufficient fluency in German; and those who were unwilling to participate. All first-time users of both treatment settings who met inclusion criteria were asked to participate. All long-term patients in both settings who met inclusion criteria were included on six randomized key days. Long-term outpatients were defined as those who had been in treatment longer than three months, and long-term inpatients had at least two admissions prior to the study.

Of a total of 448 initial subjects, 28 did not complete the study, and they were not included in our results. Of the 420 remaining patients, 129 (31 percent) were first-time outpatients, 72 (17 percent) were first-time inpatients, 126 (30 percent) were long-term outpatients, and 93 (22 percent) were long-term inpatients.

Of the 420 participants, 224 (53 percent) were male. The mean±SD age was 44±15.2 years. A total of 134 (32 percent) were employed, 122 (29 percent) received unemployment benefits, 130 (31 percent) received a pension, and 34 (8 percent) lived on private funds. A total of 161 (38 percent) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, 83 (20 percent) of alcohol or other drug use disorder, 67 (16 percent) of anxiety or adjustment disorder, 54 (13 percent) of mood disorder, 34 (8 percent) of personality disorder, and 21 (5 percent) of organic disorder.

A questionnaire was used in face-to-face interviews on six randomized key days to assess how patients rated their satisfaction with treatment. All patients were informed about the confidentiality and the voluntary nature of the study. The interviewers were trained psychologists not involved in the participants' treatment. Before the study, interviewers and treating psychiatrists successfully underwent a calibration of their ratings.

For this study, a new instrument was developed to assess patient satisfaction. Patients rated their satisfaction in three categories: staff, environment, and other patients. The three possible ratings were +1, pleasant; 0, neither pleasant nor unpleasant; and -1, unpleasant. Scores for the three categories were totaled to render an overall satisfaction score.

Patients assessed their social functioning using the Social Function Questionnaire (7) and their quality of life using the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (8). They also rated their expectations of treatment in six categories: improvement of symptoms, employment status, housing situation, social network, daily chores, and expectation of health stability. Patients rated the importance of each category on a 5-point Likert scale, from important to not important. Patients were categorized according to their expectations: patients with low expectations were those who gave ratings of 3 to 5, and those with high expectations gave ratings of 1 or 2 for at least one of the six categories.

The patients' treating psychiatrists provided information about the patients' disease severity using the Clinical Global Impressions scale (9) and about their global functioning using the Global Assessment Scale (10). The psychiatrists also provided the DSM-IV diagnosis. Sociodemographic variables were recorded in a standardized face-to-face interview. Patients and psychiatrists separately assessed the patient's current psychological and physical condition and the condition expected in one year on a scale from 0, very poor condition, to 100, very good condition. The interviewers evaluated the patients' insight into their illness.

Analyses of variance and chi square tests were used to explore the differences in satisfaction levels among the four groups. Discriminant analysis was performed to determine relationships between patient characteristics and satisfaction levels.

Results

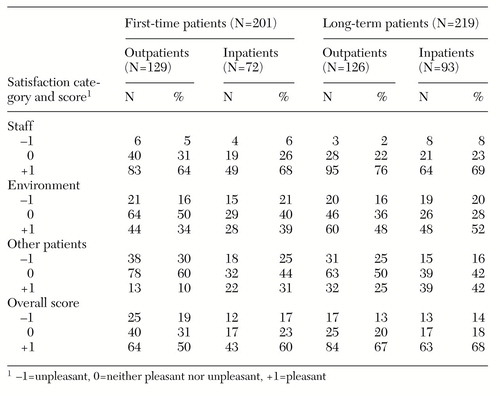

Of the 420 participants, 254 (60 percent) had a positive overall satisfaction score; 99 (24 percent) had an overall score of 0, indicating a neutral evaluation; and 67 (16 percent) had a negative overall score. As shown in Table 1, patients were most satisfied with staff and least satisfied with other patients. The percentage of patients who gave neutral answers was lowest for the staff category and highest for the other patients category.

Multivariate analysis of variance found significant main effects on satisfaction (F=3.09, df=2, p<.05). However, only first-time or long-term status was significantly associated with patient satisfaction (F=5.01, df=1, p<.05). Inpatient or outpatient setting was not related to satisfaction. The interactions between status and setting were also not significant. The chi square test showed that long-term patients had a significantly more positive impression of care than did first-time patients and that first-time patients evaluated care significantly more neutrally than did long-term patients (χ2=8.55, df=2, p<.05).

In the discriminant analysis, type of patient (first-time or long-term), setting (inpatient or outpatient), demographic variables, diagnoses, illness severity, global functioning, insight into illness, quality of life, expectations, and social functioning were used as dependent variables. Overall patient satisfaction—with staff, environment, and other patients—was used as the class variable. Five variables were included in the final classification model (χ2=34, df=10, p<.001 for all discriminant functions): type of patient (Wilks' lambda=.97, p<.01), quality of life (Wilks' lambda=.98, p<.05), social functioning (Wilks' lambda=.98, p<.05), treatment expectations (Wilks' lambda=.98, p<.05), and one-year prognosis for psychological and physical conditions (Wilks' lambda=.98, p<.05). The model of these five variables was able to classify 46 percent of the patients correctly in terms of whether they were satisfied, neutral, or unsatisfied. Only 33 percent would have been correctly classified by chance.

Discussion and conclusions

Our findings suggest that long-term patients perceived fellow patients more positively than did first-time patients, possibly because encounters with other patients suffering from acute psychosis or schizophrenic residual symptoms can be disturbing for first-time patients and may lead to such questions as, "Am I as ill as these people?" or "Will my illness be as bad as theirs?" Patients may be unwilling to express their concerns for fear of appearing discriminatory. Clinicians should address these questions at the beginning of treatment in order to reduce fears that could lead to treatment dropout.

The highest percentage of patients expressing dissatisfaction in any category was 30 percent; 30 percent of first-time outpatients found other patients unpleasant. Interestingly, 60 percent of first-time outpatients gave a neutral evaluation of other patients. This finding suggests that psychiatric patients may have difficulty in making critical comments. Future research should try to determine the underlying reasons for giving neutral answers.

In line with Holcomb and associates (2), our findings showed that a patient's one-year prognosis for psychological and physical conditions and quality of life was positively correlated with satisfaction. Our study also supports the finding that patients' ratings of their level of functioning are significantly related to satisfaction, whereas clinicians' ratings are not (2,3). The finding that high treatment expectations correspond with satisfaction should be examined in future research on the association between satisfaction and met or unmet expectations. The fit of the discriminant model, however, is rather dissatisfying, suggesting that variables other than those taken into consideration may have better differentiated between satisfied, neutral, and dissatisfied patients.

Another central concern of this study is the brief instrument we used to measure patient satisfaction, which may have limited our results. Further studies are needed to determine the validity of these findings and to identify variables related to satisfaction.

Dr. Berghofer, Dr. Lang, Ms. Henkel, Dr. Schmidl, and Dr. Schmitz are affiliated with the quality management division of Community Mental Health Services in Vienna, Austria, where Dr. Rudas is the medical director. Address correspondence to Dr. Berghofer at Community Mental Health Services, Beethovengasse 6/1, 1090 Vienna, Austria (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Satisfaction ratings of 420 first-time and long-term patients in inpatient and outpatient settings

1. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Stolar M: Patient satisfaction and administrative measure as indicators of the quality of mental health care. Psychiatric Services 50:1053-1058, 1999Link, Google Scholar

2. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB, et al: Customer satisfaction and self-reported treatment outcomes among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 49:929-934, 1998Link, Google Scholar

3. Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al: Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning 2:197-207, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Williams B, Wilkinson G: Patient satisfaction in mental health care: evaluating an evaluative method. British Journal of Psychiatry 166:559-562, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Perreault M, Rogers WL, Leichner P, et al: Patients' requests and satisfaction with services in an outpatient psychiatric setting. Psychiatric Services 47:287-292, 1996Link, Google Scholar

6. Barker DA, Shergill SS, Higginson I, et al: Patients' views towards care received from psychiatrists. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:641-646, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Tyrer P: Personality disorder and social functioning, in Measuring Human Problems. Edited by Peck DF, Shapiro CM. New York, Wiley, 1990Google Scholar

8. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, et al: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 29:321-326, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

9. Clinical Global Impressions, in ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, rev ed. Edited by Guy W. Rockville, Maryland, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976Google Scholar

10. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766-771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar