Patients' Experiences and Clinicians' Ratings of the Quality of Outpatient Teams in Psychiatric Care Units in Norway

Patients' ratings of their experiences and satisfaction with health services are a frequently used indicator of service quality ( 1 ). However, there is a limited understanding of how psychiatric units contribute to patients' perceptions of quality ( 2 ). It has been suggested that patients' satisfaction is associated with compliance and health outcome ( 1 , 3 ) and that its measurement may raise issues that the providers of services often fail to identify ( 4 ). Others have maintained that providers and patients view quality differently ( 5 ) and that both views must be considered for quality assessment. However, there is a limited understanding of the relationship between clinicians' and patients' perceptions of quality. Studies of patient satisfaction have been criticized for providing a limited picture of user views ( 6 ). Other researchers have maintained that conclusions from patient satisfaction studies are often based on weak methodological premises ( 7 ).

Several studies have linked differences in patients' experiences and satisfaction to expectations, health status, and other patient characteristics ( 8 ). The link between patient satisfaction and organizational attributes is less well understood ( 2 , 9 ). Although it has been suggested that patient satisfaction is related to the quality of services at different organizational levels, few studies have used a multilevel framework where the variance is partitioned among different levels. Multilevel analysis is an analytical approach increasingly used to investigate the relative effect of different organizational levels ( 10 ).

Findings from the United States suggest that satisfaction in somatic general medical and surgery units is primarily determined at both the patient and episode-of-care levels, with the care unit or department level accounting for less than 1% of the total variance ( 11 ). A Norwegian somatic study found significant ward-level variance (approximately 1%) in inpatients' experience of information provided ( 9 ). An Italian study of patients receiving diabetes care from either general practitioners or diabetes outpatient clinics found that approximately 4% of the variance in satisfaction was due to the setting of care or care at the physician level ( 12 ). An English study of patient satisfaction within 14 general practices found that 2%–7% of the variance occurred at the practice and physician levels of care, with the remainder due to differences between patients ( 13 ). A Dutch study found that between 5% and 10% of the variation in patient satisfaction was due to the practice or general practitioner ( 14 ).

Within mental health, a U.S. study found that differences across group-based psychosocial rehabilitation teams accounted for 10%–25% of the variance across four satisfaction scales ( 15 ), a result substantially different from the other studies cited above. It remains equivocal, however, as to whether the results from the U.S. study are due to the mental health context or to the specific profile of psychosocial rehabilitation teams. We are not aware of other studies within mental health that have assessed the specific contribution of organization level to patients' experiences. Psychiatric services are widely provided as outpatient treatment, and their impact on patients' experiences requires further study.

This study addressed the feasibility of using patients' experience ratings as a measure of organizational quality by using data from a national survey of outpatients and clinicians from Norwegian mental health services. In Norway, the state is responsible for specialized health services, which are delivered through five regional health authorities. Within each regional health authority, mental health services, such as community mental health centers and hospital-based services, are provided by health trusts. Outpatient clinics with various teams are a part of the community mental health centers. The outpatient clinics provide psychiatric services for a given population, and their teams can be defined as the lowest organizational care unit.

This study addressed two questions. The first relates to the amount of variance in patients' experiences that the different levels of care—outpatient teams, clinics, and health trusts—are able to explain. The second compares clinicians' assessment of quality with patients' experiences.

Methods

Data collection

All 15,422 persons aged 18 years or older who received services from mental health outpatient clinics in Norway in September 2004 were mailed a questionnaire within the following month. Patients were asked to rate their experience with regard to their most recent treatment episode.

The procedure regarding informed consent, study design, and collection of data was approved by the Norwegian Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, the Data Inspectorate, and the Norwegian Board of Health.

Patients' assessments of quality of care were collected via the Psychiatric Out-Patient Experiences Questionnaire (POPEQ). The POPEQ was developed after a literature review, interviews with patients, and pretesting of questionnaire items ( 16 ). Factor analysis and tests of item-discriminant validity provided empirical support for an index of overall experiences, as well as for three subscales, which also have a theoretical basis. The outcome scale comprises three items: outcome from conversations with the professional, overall treatment outcome, and change in psychological problems. The scale for assessing interaction with clinicians comprises six items: enough time for contact and dialogue, understanding, therapy and treatment suitability, follow-up actions carried out, communication, and say in treatment. The information scale comprises two items: information about treatment options and psychological problems.

The POPEQ has good evidence for reliability and validity. Item-versus-total correlations ranged from .5 to .8. Cronbach's alpha and test-retest reliability estimates exceeded the criterion of .7, with most being over .8 and POPEQ total scores over .9. Construct validity was supported by the results of 128 tests ( 16 ). The POPEQ scales, which are scored 0–100, where 100 is the best possible experience of care, are the dependent variables in the analyses that follow.

A questionnaire assessing clinicians' view of care was mailed to the clinicians via all mental health outpatient clinics in Norway in the beginning of September 2004. The questionnaire comprises four scales. Patient treatment has a Cronbach's alpha of .79 and six items: patient assessment, content of patient records, content of the discharge reports, closure of treatment episodes, the patient's influence in treatment, and overall evaluation of patient treatment. Professional competence has an alpha of .60 and two items: professional justifiable treatment and adequate competence in patient treatment. Time adequacy has an alpha of .66 and three items: the clinician's evaluation of having adequate time for each patient and for skills upgrading and ability to prioritize between important tasks. Work environment has an alpha of .90 and includes eight items: work environment, admission policy, collaboration between therapists, meetings, professional management, administrative management, personnel management, and job satisfaction. The scales are scored 0–100, where 100 is the best possible score.

Statistical analyses

The material was divided into four hierarchical levels: health trusts, outpatient clinics, teams, and patients. For outpatient clinics not divided into teams, the clinic and team level are the same. In accordance with previous studies, we hypothesized that most of the variance in patients' experiences would be between patients but that there would also be a significant contribution of the care unit to patients' experiences ( 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ). Mean team-level clinician index scores on the four scales were linked to the patients' experiences data.

The team-level mean clinician scores formed the independent variables. To control for differences in patient characteristics across the care settings, patient-level variables known to be related to patients' experiences and satisfaction were included in the analysis ( 8 , 16 , 17 ). These included age and gender, self-reported mental and physical health, duration of treatment, former inpatient history, number of visits in the past three months, and perceived waiting time.

Patients rated their experiences on the basis of shared environments, such as teams, outpatient clinics, and health trusts; therefore, analyses were performed using multilevel regression analyses ( 18 ), with the statistical program MlWin. The dependent variables were treated as continuous variables, and linear regression analyses were performed.

The regression intercepts were allowed to vary randomly across higher-level units, such as teams, outpatient clinics, and health trusts, thus making it possible to estimate the variance attributed at different levels ( 18 ). It is possible to test whether the variance at a given level is significantly larger than what could be expected by chance alone. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) is a measure of the degree of agreement between, for example, patients who received treatment at the same clinical unit ( 18 ). If, for instance, there is no concordance between patients within care units, then the ICC is zero, whereas if all patients score the same value at each care unit, then the ICC equals one. When the ICC is multiplied by 100, it can be interpreted as the percentage of variance attributed to the unit level of care.

Results

Patients receiving outpatient treatment within an inpatient setting were excluded from the analyses, which gave 6,570 (43% response rate) patients from 222 outpatient teams across 89 outpatient clinics of the 33 health trusts as respondents for this study. Compared with nonrespondents, respondents were more likely to be older and female ( 16 ). Questionnaires were returned by 1,688 clinicians. The anonymous method of data collection did not permit the calculation of the response rate for the entire sample, but in a subsample of outpatient clinics, 906 out of 973 (93%) responded to the questionnaire. It was possible to link aggregated information at the team level for 158 outpatient teams with the experiences of 5,542 patients.

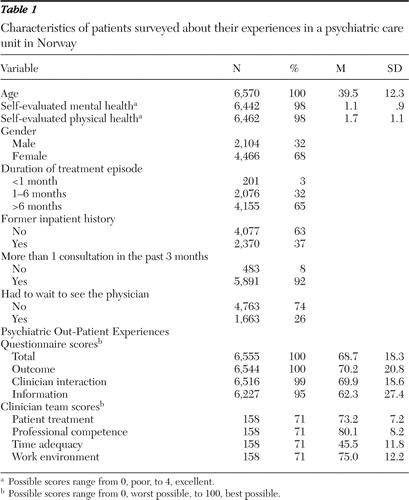

Table 1 shows that the mean±SD age of patients was 39.5±12.3 years and that 68% of the sample were female. POPEQ total, outcome, and clinicians' interaction scores were close to 70, whereas the information score was about 62. The team mean clinician score ranged from 45 to 80.

|

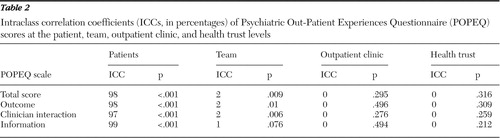

Table 2 shows the variance in patients' experiences that were attributable to each of the four levels of analysis, without any other explanatory variables. The POPEQ scores were partitioned into patient level, team level, clinic level, and health trust level of care. There was significant variance between teams but not between outpatient clinics or between health trusts. However, two-level models including the patients and clinics, or the patients and health trust levels separately, showed small but significant variance at both the clinic and health trust levels.

|

Just 2% of the differences in the POPEQ total, outcome, and clinician interaction subscale scores were attributable to the team level, with 98% attributed to the patients' variance within teams. POPEQ scores for the information scale did not vary significantly between any of the care unit levels; that is, there was no organizational contribution to the variance in this scale.

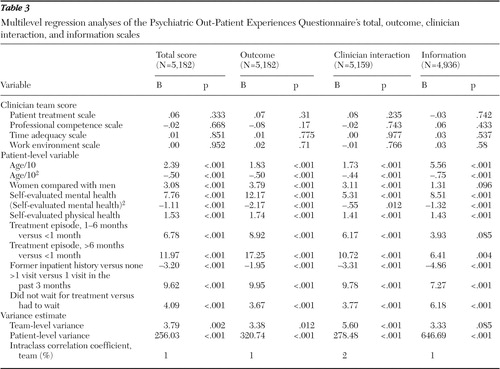

Table 3 shows parameter estimates and p values for the independent variables. With this analysis no additional variance remained between clinics or health trusts; therefore, we used two-level models, namely patients within teams. The models in Table 3 comprise patient- and team-level variables. There was a significant team-level variance, hence independent variables for care unit were used at the team level. The teams contributed 1%–2% of the variance in POPEQ scores after the analyses controlled for patient- and team-level characteristics. There were no significant associations between any of the clinician indices and the POPEQ scales.

|

There was a significant concave, curvilinear association between age and POPEQ scores, with older patients having better experiences. Women reported significantly better experiences than men for all POPEQ scores, with the exception of the information scale. Higher self-reported mental and physical health were significantly associated with better experiences, the former association being concave curvilinear and the latter being linear.

There was a significant correlation between duration of the current treatment episode and POPEQ scores. This was strongest for the outcome scale, where patients whose treatment was longer than six months had better experiences compared with those in treatment for less than one month, with a difference of approximately 17 scale points. Former inpatients reported significantly poorer POPEQ scores than patients who had not been inpatients. Patients with more than one visit over the past three months had better experiences for all POPEQ scores. Patients who felt that they had to wait for treatment reported poorer POPEQ scores.

Discussion

We found that most of the differences in patients' experiences, as measured by the POPEQ, could be attributed to differences between patients rather than the care unit in which they were treated. There was some significant variance between teams but no independent variance between outpatient clinics or between trusts.

The marginal difference that was found between care units might lead to the suggestion that measures of patients' experiences and satisfaction lack the discriminatory power necessary for comparison at the organizational level, including mental health institutions. However, it is also possible that the care provided at this level is fairly uniform across organizations. Policies or guidelines that are being followed by trusts and outpatient clinics may lead to small quality differences at the organizational level. Studies of outpatient treatment have, however, found considerable variation between clinicians in their response to clinical guidelines ( 19 ).

It has been argued that many patient satisfaction studies lack reliability and validity, which casts doubt on the credibility of the findings ( 20 ). The questionnaire used in this study, the POPEQ, has good reliability and validity in terms of its power to discriminate between different groups of patients ( 16 ). However, the POPEQ did not measure substantial differences at the organizational level, even if there was a large total variance in the scale scores. In fact, the POPEQ scale of information had the largest total variance but did not have any significant variance between care units. That is, many patients were dissatisfied with the information provided, but this dissatisfaction was similar across care units. It follows that the large total variance in scores was not necessarily measuring quality differences in the environment that provided the treatment.

The results from this study draw attention to what may be defined as a substantial environmental context for patients. Administrative units, such as clinics, may be meaningful categories for clinicians and health service administrators in organizing services but not for assessing differences in patients' experiences. Within Norwegian mental health outpatient clinics, most patients receive individual therapy with only one clinician, and the patients have little contact with other patients in the same care units. These factors may explain why we found only minor differences between teams, whereas a study of psychosocial rehabilitation teams found 10%–25% contextual variance ( 15 ), indicating teams that work more coherently than our general outpatient teams. The low variance at the care unit level could be due to large individual practice differences within each unit and across all units. The therapist effect on treatment outcome is shown to be of high importance, as is the patient-clinician alliance ( 21 ). We were not able to assess patients' experiences for individual clinicians. Further studies are needed to determine the variance in patient satisfaction between clinicians compared with that between teams.

The results showed that almost all of the variance in patients' experiences could be attributed to differences between patients. However, we did not have data that allowed us to assess any change in patients' experiences during the treatment period. One study found considerable within-patient variance ( 11 ), which suggests that patients' experiences and satisfaction vary between each episode of care. Given that most mental health outpatients have several consultations, further analyses are needed to understand more about changes in patients' experiences during the treatment period.

Our study found low concordance between the quality perceived by the clinicians in teams and by the patients receiving care from the same teams, which may be a consequence of the low team-level variance in patients' ratings. This finding is in contrast to other findings of clinicians' confidence in the results of patients' experiences and satisfaction studies ( 22 ). On the other hand, the low concordance may indicate that patients' and clinicians' evaluations are different and that both may contribute to the understanding of quality differences from separate viewpoints ( 5 ). This result could also indicate that clinicians buffer problems in their work environment in order to secure adequate treatment for their patients. That is, clinicians do not let their perceptions of the professional quality, competence, time adequacy, and work environment influence treatment quality, as perceived by the patients. Other studies have also reported weak or nonexistent associations between average levels of provider ratings and patients' experiences ( 23 ). One found a weak but significant association for one of several different items and scales that measured the average level of nurses' job satisfaction at the ward level and patients' experience with information ( 9 ). Another showed a significant relationship with team burnout as experienced by the clinicians and patients' satisfaction ( 15 ).

Similar to previous findings, age was positively associated with patients' experiences, and women reported better experiences than men ( 8 , 16 ). Health status was positively associated with patients' experiences ( 8 , 24 , 25 ). Both the frequency and duration of the current treatment episode were related to higher POPEQ scores. Former inpatients reported poorer experiences. Perceived longer waiting times were negatively related to patients' experiences ( 17 ).

The modest response rate from patients should be taken into consideration. Low response rates area problem in mental health user surveys ( 26 , 27 , 28 ), and the response rate for the POPEQ was consistent with previous findings. The literature in general is not conclusive on the consequences of low response rates ( 29 , 30 , 31 ).

Conclusions

Aggregated results from surveys of patients' experiences and satisfaction of outpatients have limitations as a single indicator of organizational quality. Administrative units, such as teams and clinics, may not represent important environmental contexts for patients receiving care. For patients receiving individual therapy, the relationship with the clinician is likely to be more important than the organization in which the care has been provided. The results of this study suggest that patients' experiences and satisfaction data are likely to have greater applicability at the clinician level. Future research should assess intrapatient change in satisfaction during a treatment episode, for instance, for purposes of evaluating alternative approaches to care delivery, including clinical trials. Provider ratings of quality cannot be substituted for patients' perceptions of quality but should also be considered when service quality is measured.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The collection of data was funded by the Social and Health Directorate in Norway. The writing of the report was funded by the Norwegian Council for Mental Health. The views expressed are those of the authors.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Powell R-A, Holloway F, Lee J, et al: Satisfaction research and the uncrowned king: challenges and future directions. Journal of Mental Health 13:11–20, 2004Google Scholar

2. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Stolar M: Patient satisfaction and administrative measures as indicators of the quality of mental health care. Psychiatric Services 50:1053–1058, 1999Google Scholar

3. Ruggeri M, Lasalvia A, Dall'Agnola R, et al: Development, internal consistency and reliability of the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale—European Version. EPSILON Study 7. European psychiatric services: inputs linked to outcome domains and needs. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement 39:S41–S48, 2000Google Scholar

4. Pilgrim D, Rogers A: A confined agenda? Journal of Mental Health 6:539–542, 1997Google Scholar

5. Shannon SE, Mitchell PH, Cain KC: Patients, nurses, and physicians have differing views of quality of critical care. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 34:173–179, 2002Google Scholar

6. Williams B: Patient satisfaction: a valid concept? Social Science and Medicine 38:509–516, 1994Google Scholar

7. Salzer M: Consumer satisfaction [letter]. Psychiatric Services 49:1622, 1998Google Scholar

8. Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, et al: The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technology Assessment 6:1–244, 2002Google Scholar

9. Veenstra M, Hofoss D: Patient experiences with information in a hospital setting: a multilevel approach. Medical Care 41:490–499, 2003Google Scholar

10. Leyland A, Goldstein H: Multilevel modeling of health statistics. New York, Wiley, 2001Google Scholar

11. Aiello A, Garman A, Morris SB: Patient satisfaction with nursing care: a multilevel analysis. Quality Management in Health Care 12:187–190, 2003Google Scholar

12. Franciosi M, Pellegrini F, De Berardis G, et al: Correlates of satisfaction for the relationship with their physician in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 66:277–286, 2004Google Scholar

13. McKinley RK, Roberts C: Patient satisfaction with out of hours primary medical care. Quality and Safety in Health Care 10:23–28, 2001Google Scholar

14. Sixma HJ, Spreeuwenberg PM, van der Pasch MA: Patient satisfaction with the general practitioner: a two-level analysis. Medical Care 36:212–229, 1998Google Scholar

15. Garman AN, Corrigan PW, Morris S: Staff burnout and patient satisfaction: evidence of relationships at the care unit level. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 7:235–241, 2002Google Scholar

16. Garratt A, Bjørngaard JH, Aanjesen Dahle K, et al: The Psychiatric Out-Patient Experiences Questionnaire (POPEQ): data quality, reliability and validity in patients attending 90 Norwegian clinics. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 60:89–96, 2006Google Scholar

17. Siponen U, Valimaki M: Patients' satisfaction with outpatient psychiatric care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 10:129–135, 2003Google Scholar

18. Hox J: Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 2002Google Scholar

19. Grol R, Grimshaw J: From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet 362:1225–1230, 2003Google Scholar

20. Sitzia J: How valid and reliable are patient satisfaction data? An analysis of 195 studies. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 11:319–328, 1999Google Scholar

21. Wampold BE: The Great Psychotherapy Debate: Models, Methods and Findings. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 2001Google Scholar

22. Valenstein M, Mitchinson A, Ronis DL, et al: Quality indicators and monitoring of mental health services: what do frontline providers think? American Journal of Psychiatry 161:146–153, 2004Google Scholar

23. Macpherson R, Jerrom B, Alexander M, et al: A survey of patient and keyworker satisfaction with the Gloucester mental health rehabilitation service. Journal of Mental Health 7:367–374, 1998Google Scholar

24. Berghofer G, Lang A, Henkel H, et al: Satisfaction of inpatients and outpatients with staff, environment, and other patients. Psychiatric Services 52:104–106, 2001Google Scholar

25. Ruggeri M, Pacati P, Goldberg D: Neurotics are dissatisfied with life, but not with services. The south Verona outcome project 7. General Hospital Psychiatry 25:338–344, 2003Google Scholar

26. Ruggeri M: Satisfaction with psychiatric services, in Mental health Outcome Measures. Edited by Thornicroft G, Tansella M. Berlin, Germany, Springer, 1996Google Scholar

27. Rosenheck R, Wilson NJ, Meterko M: Influence of patient and hospital factors on consumer satisfaction with inpatient mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services 48:1553–1561, 1997Google Scholar

28. Hansson L: Patient satisfaction with in-hospital psychiatric care: a study of a 1-year population of patients hospitalized in a sectorized care organization. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 2:93–100, 1989Google Scholar

29. McColl E, Jacoby A, Thomas L, et al: Design and use of questionnaires: a review of best practice applicable to surveys of health service staff and patients. Health Technology Assessment 5(31):1–256, 2001Google Scholar

30. Zwier G, Clarke D: How well do we monitor patient satisfaction? Problems with the nation-wide patient survey. New Zealand Medical Journal 112:371–375, 1999Google Scholar

31. Rubin HR: Patient evaluations of hospital care: a review of the literature. Medical Care 28(suppl):3–9, 1990Google Scholar