The Case Management Relationship and Outcomes of Homeless Persons With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The effect of the case management relationship on clinical outcomes was examined among homeless persons with serious mental illness. METHODS: The sample consisted of the first two cohorts that entered the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program, a five-year demonstration program for mentally ill homeless persons funded by the Center for Mental Health Services in 1994. At baseline, three months, and 12 months, clients were characterized as not having a relationship with their case manager or as having a low or high therapeutic alliance with their case manager. Analyses were conducted to test the association between the case manager relationship at baseline, three months, and 12 months and clinical outcomes at 12 months. RESULTS: Multivariate analyses of covariance were conducted for 2,798 clients who had outcome data at 12 months. No significant associations were found between the relationship with the case manager at baseline and outcomes at 12 months. At three months, clients who had formed an alliance with their case manager had significantly fewer days of homelessness at 12 months. Clients who reported a high alliance with their case manager at 12 months had significantly fewer days of homelessness at 12 months than those with a low alliance, and those with a low alliance at 12 months had fewer days of homelessness than clients who reported no relationship with their case manager. Clients with a higher alliance at both three and 12 months reported greater general life satisfaction at 12 months. CONCLUSIONS: The study found that clients' relationship with their case manager was significantly associated with homelessness and modestly associated with general life satisfaction.

Case management for individuals who are homeless and have a mental illness has become an increasingly common service provided by public mental health systems. In a recent review by Morse (1), the most consistent finding was that clients in a variety of case management models spent fewer days homeless than those in standard care and showed improvements in symptoms and self-esteem. However, the basis for this effectiveness is largely unexplained.

There is some evidence that the strength of the case management relationship or the therapeutic alliance mediates clinical outcomes (2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9). Many definitions of the therapeutic alliance exist (10,11,12), but two general dimensions are included in virtually all definitions: the quality of the interpersonal relationship between the client and the therapist, which includes trust, respect, and genuine affection, and the degree to which the client is engaged in the treatment and is working collaboratively with the therapist toward achieving the goals of the therapy. The study reported here used a modified version of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI), an instrument developed by Horvath and Greenberg (13) to assess the treatment alliance.

Although these studies of therapeutic alliance and outcome have yielded important results, they suffer from several notable methodological limitations. Three studies (4,8,9) used a retrospective approach in which alliance and outcome were measured at the same time, toward the end of the study period. These studies were able to document only an association between alliance and clinical outcomes measured at the same point in time—that is, a concurrent relationship.

A second methodological issue also concerns when in the course of treatment the therapeutic alliance should be measured. Among the four studies that used a prospective analytic approach, one used alliance ratings taken at the very start of the clinical intervention, during hospitalization (3). Clients and providers in that study may have had difficulty meaningfully assessing the strength of the relationship because it had not had time to develop. The other three studies rated the alliance two to nine months after the start of treatment (5,6,7). After many months of treatment, the ratings could have been confounded by overall improvement.

A third characteristic of past studies is that they have focused mostly on hospital inpatients or outpatients with long-term involvement in mental health services who are participating in intensive case management services such as assertive community treatment. Only one study prospectively explored the connection between the therapeutic relationship and outcomes among clients who were homeless and had a mental illness (7). These individuals can be especially difficult to engage in treatment because of their severe psychiatric impairment, substance abuse, negative previous experiences with the service system, and desire to meet their more immediate material needs first (14,15,16). Therapeutic alliance thus may be an especially important factor influencing the outcomes of treatment for this often distrustful group.

In this study we assessed the association between the therapeutic alliance measured at three time points and clinical outcomes at 12 months among clients who were homeless and had a mental illness. Both the presence and the quality of the therapeutic alliance were evaluated at baseline, at three months, and concurrently with the outcome assessment at 12 months. The study sought to contribute to the growing understanding of the relationship between therapeutic alliance and outcomes among homeless persons with mental illness.

Methods

The ACCESS program

Funded by the Center for Mental Health Services as a five-year demonstration program in 1994, the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program was designed to test whether integrated systems of service delivery would enhance the use of services, outreach, and the quality of life of homeless people with serious mental illness (17). ACCESS programs were implemented in 18 communities in 15 cities, representing major geographical areas of the continental U.S. The programs provided outreach and intensive case management to 100 homeless people with severe mental illnesses at each site for four successive years. The study reported here focused on the first two cohorts that entered the ACCESS program.

Data sources and eligibility

Before enrolling in case management services, eligible clients provided written informed consent and completed a structured baseline interview that documented sociodemographic characteristics, housing status, psychiatric symptoms, substance use, length of time homeless, physical health status, social support, employment, income, criminal involvement, general life satisfaction, service use, and victimization experiences. Clients repeated this interview, which is described below, three months and 12 months after entering the program.

Eligibility criteria for ACCESS case management services addressed homelessness, the presence of severe mental illness, and involvement in ongoing community treatment (18). Clients were considered homeless if at the time of first contact with ACCESS staff, they had spent at least seven of the past 14 nights in a shelter, outdoors, or in a public or abandoned building. To determine the presence of severe mental illness, a screening algorithm that had been developed for a previous outreach demonstration project for homeless people with severe mental illness was used (19). The Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis (SCID) was used as a standard to validate this algorithm. It demonstrated 91 percent sensitivity, that is, it correctly identified 91 percent of persons with axis I psychiatric disorders, not including substance use disorders (19). The SCID was used only to assess whether the screening algorithm correctly identified true cases, and therefore specificity was not evaluated. The interviews were administered by trained interviewers who were not involved in the delivery of clinical services.

Measures

Presence or absence of a case manager. A dichotomous variable indicated whether or not clients reported having an ACCESS case manager. Clients were asked, "Is there one person who has been your primary clinician, or who knows the most about your treatment?" Although all ACCESS clients were assigned a case manager, this variable assesses, from their own point of view, whether they experienced a personal connection with their case manager.

Therapeutic alliance. We used the Therapeutic Alliance Scale, originally developed by Horvath and Greenberg (13) and modified by Neale and Rosenheck (7) for use with an intensive case management program. It uses a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 0, indicating never, to 6, indicating always. It assesses the level of trust, conflict, agreement on the goals of treatment, confidence in the clinician's abilities, and overall importance of the relationship to the client. Possible scores ranged from 0, indicating no alliance, to 52, indicating high alliance. This measure was completed by all clients who identified themselves as having a relationship with a case manager. The internal consistency of the measure was excellent in this study (Cronbach's alpha=.89 at baseline, .89 at three months, and .90 at 12 months).

Demographic variables. We used the variables of race (coded as a dummy variable, African American=1), gender (male=1), age (in years), and education level (number of years of school completed) because they have been shown to be related to alliance and presence or absence of a case manager (2).

Clinical and social functioning. We also assessed level of social support, as measured by the number of types of people the client could count on for a loan, a ride to an appointment, or help with an emotional crisis (20); possible scores ranged from 0 to 18, depending on the types of people named by the client. Homelessness was measured as the number of days homeless in the past 60 days.

Depression was measured as the sum of five dichotomous items indicating the presence of depression in the past month; possible scores ranged from 0, indicating no symptoms of depression, to 5, indicating serious depression. Client-rated psychosis was the sum of ten items indicating the presence of psychotic symptoms in the past month; each item ranged from 0, never, to 4, very often. Possible scores ranged from 0, indicating an absence of psychosis, to 40, indicating the frequent experience of many psychotic symptoms.

Two identical items asked at different points in the interview were from the Lehman (21) Quality of Life Interview. They assessed the client's general life satisfaction, which was rated from 1, terrible, to 7, delighted; the two ratings were averaged.

A subjective rating of general psychiatric problems was made using a composite variable consisting of 11 items from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (22). Each item was weighted so that possible scores on the scale ranged from 0, indicating no psychiatric problems, to 1, indicating severe problems.

Substance abuse. Two composite variables from the ASI were used to assess the level of substance abuse. The first comprised six items measuring the frequency and amount of alcohol use and its associated symptoms, such as craving. The second comprised 11 items measuring the frequency and amount of drug use and its associated symptoms.

Analyses

Independent, dependent, and covariate variables. The case manager relationship was the primary independent measure in this study. At each of the three time points, clients who reported no relationship with their case manager were identified. We divided clients who reported a relationship into two groups—those with low alliance and those with high alliance. We used a median split of the alliance scores from three and 12 months (43 for each time point). Scores at the latter time points reflected a treatment relationship that had time to develop.

The dependent variables were psychiatric symptoms, social functioning, and substance abuse measured at 12 months. Since initial differences in demographic characteristics, psychiatric symptoms, social functioning, and substance abuse could have confounded our analyses, the baseline variables that were significantly associated with the therapeutic alliance or clinical change were included as covariates in all subsequent analyses.

MANCOVAs. We conducted three one-way multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs) on all the dependent measures described above using the case manager relationship (no relationship, low alliance, and high alliance) as the independent variable. We conducted a one-way MANCOVA for each time the relationship was assessed: baseline, three months, and 12 months.

To understand the effect of the presence of a relationship with a case manager combined with the incremental effect of having a stronger alliance, univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with four single-degree-of-freedom contrasts were conducted using the Bonferroni correction for the set of analyses (alpha=.05/27= .002). The four contrasts evaluated the effect of high alliance plus low alliance versus no relationship, high alliance versus low alliance, low alliance versus no relationship, and high alliance versus no relationship. All the analyses in this study were conducted using SPSS for Windows, version 9.0.

Results

Sample characteristics

During the first two years of program operation, from May 1994 to April 1996, a total of 3,481 clients provided written informed consent and completed baseline assessments. The clients' mean±SD age was 38.5±9.5 years. A total of 2,242 clients (64 percent) were males; 1,576 (45 percent) were African American, and 195 (6 percent) were of Hispanic origin.

All clients had at least one axis I disorder. Some clients had more than one diagnosis. A total of 1,576 clients (45 percent) had major depression, 1,358 (39 percent) had schizophrenia, 766 (22 percent) had other psychoses, 835 (24 percent) had personality disorder, 662 (19 percent) had anxiety disorder, and 696 (20 percent) had bipolar disorder. A total of 2,297 clients (66 percent) had a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder—schizophrenia, other psychosis, or bipolar disorder.

The mean±SD score on the depression scale, which could range from 1 to 5, was 3.3±2. The mean± SD client rating on the psychosis measure, which could range from 1 to 40, was 11.5±9.4. The interviewers' mean±SD rating of general psychiatric problems, which could range from 1 to 52, was 11.4±8.6.

In addition, 1,532 clients (44 percent) had alcohol use disorders, and 1,323 (38 percent) had drug use disorders. The mean±SD number of reported days a month intoxicated was 2.2±6. The mean number of days using illegal drugs in the past month was 3.8±11.2; using more than one drug a day could produce a drug use total score greater than 30.

The average level of social support was low, 2.1±5.3 out of a possible 18. At baseline, clients reported being homeless for a mean of 38.3±21 days in the past 60 days. At baseline, the mean number of days reported working in the past 30 days was 1.9±5, and the mean monthly income was $330.14±$490.30.

Program entry and follow-up

As noted, during the first two years of program operation, 3,481 clients completed baseline assessments. At 12 months, 2,798 clients (80.4 percent) completed the final interview. A logistic regression yielded two variables that significantly predicted successful follow-up at 12 months. Clients interviewed at 12 months were less likely to be male and more likely to be African American than those who were lost to follow-up.

Case manager relationship

At baseline, 2,283 clients (78.9 percent) reported no relationship with the case manager, 348 (12 percent) were in the low-alliance group, and 261 (9 percent) were in the high-alliance group. At three months, 1,369 clients (47.6 percent) reported no relationship, 714 (24.8 percent) were in the low-alliance group, and 791 (27.5 percent) were in the high-alliance group. Compared with baseline, significantly more clients were in the low- and high-alliance groups and fewer were in the no-relationship group (χ2=165.34, df=4, p<.001; N=2,486).

At 12 months, 1,324 clients (46.1 percent) reported no relationship, 761 (26.5 percent) were in the low-alliance group, and 784 (27.3 percent) were in the high-alliance group. These proportions were also significantly different from those at baseline (χ2=106.07, df=4, p<.001; N=2,829), but they did not differ significantly from those at three months.

The absolute value of the alliance measure, which could range from 0 to 52, remained fairly consistent across the three time points. The mean±SD score for the 348 clients in the low-alliance group at baseline was 31.7±9.6, for the 714 low-alliance clients at three months it was 32.8±8.7, and for the 761 low-alliance clients at 12 months it was 32.6±8.6. These scores were not significantly different from each other. Similarly, the mean for the 261 clients in the high-alliance group at baseline was 47.9±2.7, for the 783 high-alliance clients at three months it was 47.8±3, and for the 784 high-alliance clients at 12 months it was 48.1±3. The scores for the high-alliance groups were not significantly different from each other.

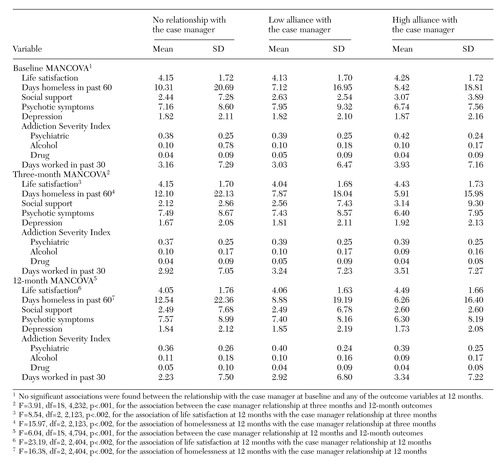

Case manager relationship and outcomes

Table 1 shows the results of the MANCOVAs at the three time points. The first MANCOVA was not significant, indicating that no differences in any of the dependent measures at 12 months were associated with the clients' reported relationship with their assigned case manager at baseline. The second MANCOVA, which used data from the three-month assessment, was significant, indicating that one or more of the dependent measures at 12 months differed significantly on the basis of the case manager relationship at three months.

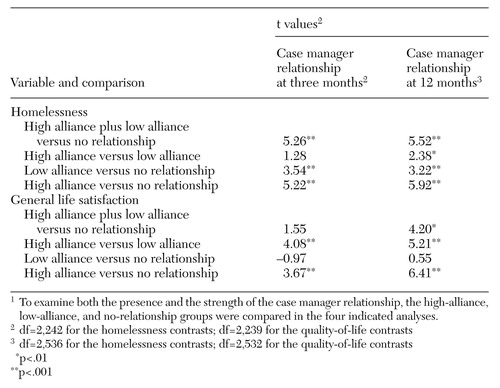

Table 2 shows the results of the univariate analyses that examined four different groups: high-alliance plus low-alliance clients versus those with no relationship, high-alliance clients versus low-alliance clients, low-alliance clients versus those with no relationship, and high-alliance clients versus those with no relationship. The three comparisons that were significant at three months indicated that the presence of a relationship, regardless of its strength, was associated with fewer days of homelessness.

As Table 1 shows, at three months the group reporting no relationship with the case manager reported having spent a mean of 12.10 days homeless in the past 60 days, compared with a mean of 7.87 for the low-alliance group and a mean of 5.91 for the high-alliance group. Thus the low-alliance group had 35 percent fewer days of homelessness than the group with no relationship, and the high-alliance group had 50 percent fewer.

For general life satisfaction, which was rated from 1 to 7, with higher ratings indicating more satisfaction, two of the contrasts in Table 2 were significant, indicating that a higher alliance was associated with higher general life satisfaction. At three months, clients in the high-alliance group had a mean satisfaction rating of 4.43, compared with 4.15 in the no-relationship group and 4.04 in the low-alliance group. Thus the satisfaction rating of the high-alliance group was 6 percent higher than the no-relationship group and 8 percent higher than the low-alliance group.

The third MANCOVA, which used data from the 12-month assessment, was also highly significant. The individual measures that were significant from the univariate ANOVA were days of homelessness and general life satisfaction. As Table 2 shows, all four comparisons were significant for days of homelessness, indicating that the presence of the case manager relationship itself was associated with reduced homelessness. Table 1 shows that clients in the high-alliance group at 12 months reported having spent 6.26 days homeless in the past 60 days, compared with 12.54 days for those in the no-relationship group and 8.88 days for those in the low-alliance group. Thus, compared with the clients who had no relationship with their case manager at 12 months, those in the low-alliance group had 29 percent fewer days of homelessness and those in the high-alliance group had 50 percent fewer.

As shown in Table 2, the three contrasts at 12 months that were significant for general life satisfaction indicated that a high alliance was associated with improvements in general life satisfaction. The general life satisfaction ratings of clients in the high-alliance group were 10 percent higher than those of clients in the other two groups.

Discussion and conclusions

By assessing the presence and strength of the case manager relationship at three different time points—baseline, three months, and 12 months—we were able to examine both temporally predictive and concurrent relationships between these variables and clinical outcomes. The presence or strength of the client-case manager relationship at baseline was not associated with any of the 12-month outcome variables, perhaps because it was too early in the relationship for any meaningful associations to be found with later outcomes.

Using data from the three-month assessments, we found that the presence and strength of the case manager relationship was related to reduced homelessness at 12 months. ACCESS specifically targeted homeless people with mental illness. Clients who were able to develop a relationship with their case manager by three months seemed to reap the benefit of fewer days of homelessness later on. Thus the relationship was temporally predictive.

A similar relationship was found between alliance and general life satisfaction, although this relationship was much weaker. When clients have stronger working relationships, they may be able to use the treatment to improve their lives to such a degree that they experience a more general satisfaction with life. Another explanation might be that a stronger relationship with a therapist itself leads to clients' feeling less isolated and more supported, resulting in an increase in general life satisfaction.

The study showed that at three months, the presence of a relationship was associated with reduced homelessness at 12 months and that there was an even larger reduction in the number of days spent homeless among clients with a greater alliance. By 12 months, the clients and case managers had more time to forge stronger relationships. This stronger alliance may have enabled clients to use the relationship productively and hence to spend fewer days homeless.

Several limitations of this study deserve comment. First, the ACCESS project was not specifically designed to assess the effects of the establishment of a case manager relationship and the therapeutic alliance on client outcomes—specifically, clients were not randomly assigned to treatment groups. Data for the independent variable was from a single item in which clients were asked to report whether or not they had a significant relationship with their case manager. The psychometric properties of this item are not known. Clients may not have reported having a relationship with one case manager if they received treatment equally from several members on the case management team.

In addition, because of the lack of random assignment, selection biases affected the results, causing the estimated effects to appear larger than they are. Also, the initial selection biases may have created group differences when none existed. Factors other than those used as covariates in the analyses may have affected the dependent measures.

Although we examined the therapeutic relationship between the clients and their case managers, we primarily focused on the reports of the clients. Input from case managers can also be important in determining the formation and strength of the therapeutic relationship. Mental health providers and clients often have different perspectives on treatment, which can affect the treatment relationship (18; Kloos B, Rappaport J, Bouas K, et al, unpublished data, 1998). Therefore, future studies should not only examine the relationship of clinicians' characteristics, such as demographic variables, training, and discipline, to the therapeutic relationship but should also include the perspective of the case manager on the formation and strength of the relationship.

In addition, although the ratings showed an improvement in general life satisfaction, it was small, and its clinical relevance is unclear. Future studies should attempt to link various degrees of improvement to additional outcomes to assess clinical relevance.

Finally, even though the design incorporated temporal prediction, it is still possible that attaining more satisfaction with life and spending less time homeless resulted in a better relationship with the case manager. Causality is difficult to determine. The causal ambiguity may be especially true for the concurrent analyses at 12 months because clinical improvements could influence clients' reports of the status of the case manager relationship.

Although our measure of the case manager relationship had only a limited ability to predict clinical outcomes, the findings suggest that when a treatment alliance is established, clients experience fewer days of homelessness and greater life satisfaction. Further study of these constructs will help guide clinicians and program developers to make more effective interventions on behalf of this troubled population.

Dr. Chinman is assistant professor and Dr. Rosenheck is clinical professor in the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Chinman is also director of program evaluation services at the Consultation Center, 389 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Rosenheckis also director of the Department of Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center (NEPEC) in West Haven, Connecticut. The late Dr. Lamwas an associate research scientist at Yale University School of Medicine and associate director of NEPEC.

|

Table 1. Multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs) of the relationship between the therapeutic alliance with the case manager and other variables for the clients in the ACCESS program, by whether clients reported no relationship with the case manager or a low or high allinace

|

Table 2. Association of homelessness and life satisfaction at 12 months to clients' relationship with their case manager at three and 12 months1

1 To examine both the presence and the strength of the case manager relationship, the high-allinace, low-alliance, and no-relationship groups were compared in the four indicated analyses

1. Morse G: A review of case management for people who are homeless: implications for practice, policy, and research. Presented at the National Symposium on Homelessness Research, Arlington, Va, October 29-30, 1998Google Scholar

2. Allen JG, Tarnoff G, Coyne L: Therapeutic alliance and long-term hospital treatment outcome. Comprehensive Psychiatry 26:187-194, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Clarkin JF, Hurt SW, Crilly JL: Therapeutic alliance and hospital treatment outcome. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:871-875, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Frank AF, Gunderson JG: The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of schizophrenia: relationship to course and outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:228-236, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Gehrs M, Goering P: The relationship between the working alliance and rehabilitation outcomes of schizophrenia. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 18(2):43-54, 1994Google Scholar

6. Goering P, Wasylenki D, Lindsay S, et al: Process and outcome in a hostel outreach program for homeless clients with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:607-617, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Neale MS, Rosenheck RA: Therapeutic alliance and outcome in a VA intensive case management program. Psychiatric Services 46:719-721, 1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Solomon P, Draine J, Delaney MA: The working alliance and consumer case management. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:126-134, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Chinman M, Rosenheck R, Lam J: The development of relationships between homeless mentally ill clients and their case managers. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 23:47-55, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Bordin ES: The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy 16:252-260, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Greenson RR: The Technique and Practice of Psychoanalysis. New York, International Universities Press, 1967Google Scholar

12. Luborsky LL: Helping alliances in psychotherapy, in Successful Psychotherapy. Edited by Claghorn JL. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1976Google Scholar

13. Horvath AO, Greenberg L: Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology 36:223-233, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Appleby L, Slagg N, Desai PN: The urban nomad: a psychiatric problem? Current Psychiatric Therapies 21:253-262, 1982Google Scholar

15. Bachrach L: Dimensions of disability in the chronic mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:981-982, 1982Google Scholar

16. Lamb HR: Young adult chronic patients: the new drifters. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 33:465-468, 1982Abstract, Google Scholar

17. Randolph FL, Blasinsky M, Legenski W, et al: Creating integrated service systems for homeless persons with mental illness: the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 48:369-373, 1997Link, Google Scholar

18. Rosenheck R, Lam J: Homeless mentally ill consumers' and providers' perceptions of needs of service and consumers' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381-386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

19. Shern DL, Lovell AM, Tsembris S, et al: The New York City outreach project: serving a hard-to-reach population, in Making a Difference: Interim Status Report of the McKinney Demonstration Program for Homeless Adults With Serious Mental Illness. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1994Google Scholar

20. Vaux A, Athanassopulou M: Social support appraisals and network resources. Journal of Community Psychology 15:537-556, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

22. McClellan T, Luborsky L, Woody G, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26-33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar