Quality of Life of Homeless Persons With Mental Illness: Results From the Course-of-Homelessness Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The quality of life of homeless persons with mental illness was compared with that of homeless persons without mental illness. METHODS: Subjective and objective quality-of-life ratings were obtained in face-to-face interviews with 1,533 homeless adults in Los Angeles, who were identified using probability sampling of people on the streets and at shelters and meal facilities; 520 subjects were tracked for 15 months. Ratings of homeless persons with and without mental illness were compared using chi square tests and regression analyses. RESULTS: Mentally ill homeless persons were significantly more likely than those without mental illness to receive Supplemental Security Income, Social Security Disability Insurance, Veterans Affairs disability benefits, or Medicaid. However, those with mental illness still fared significantly worse in terms of physical health, level of subsistence needs met, victimization, and subjective quality of life. Differences between groups in the subjective quality-of-life ratings were accounted for by modifiable factors such as income and symptoms rather than by nonmodifiable demographic characteristics. CONCLUSIONS: Interventions most likely to improve the quality of life of homeless persons with mental illness include those that stress maintenance of stable housing and provision of food and clothing and that address physical health problems and train individuals to minimize their risk of victimization. Interventions that decrease depressive symptoms might also improve subjective quality of life.

Over the past decade, local, state, and national studies have revealed that 20 to 25 percent of the homeless population have mental disorders such as schizophrenia, severe and recurrent major depression, and bipolar disorder (1). Although it might be expected that all homeless persons, and especially those with mental illness, have a poorer quality of life than individuals in the general population, it is possible that homeless persons with mental illness fare better than other homeless persons.

Unlike homeless persons who do not have mental illness, many homeless persons with mental disorders are eligible for and receive disability payments from Social Security or the Department of Veterans Affairs. In addition, persons with mental illness often receive assistance in obtaining housing and benefits through public mental health outreach programs (2,3,4,5). In some states, such as California (6), funds to aid homeless persons have been channeled through mental health agencies specifically to persons with mental illness, who are often seen as a more deserving segment of the homeless population.

The course-of-homelessness study, which was conducted in Los Angeles County between October 1990 and September 1991 and which included a probability sample of homeless persons, was the first to rigorously study the well-being of homeless persons and to examine variations in quality of life across homeless subpopulations, such as those with mental illness (7). In recent years quality of life and well-being have received more emphasis in both clinical and services research, and measures of such constructs have undergone considerable development (8). Reliable and valid instruments have been created specifically for persons with serious mental illness (9). They are modeled after assessments of quality of life in the general population (10), which include both objective and subjective quality measures across several life domains.

Such assessments are especially important for those with persistent, disabling mental disorders, because the goal of their treatment is often to maximize quality of life. Further, from a social policy perspective, quality-of-life assessments allow us to better understand how persons with mental illness are faring in a variety of noninstitutional settings, including the streets and homeless shelters.

Previous studies of quality of life of the homeless population (11,12) and persons with mental illness (13,14,15) have explored factors within the two populations that are associated with better quality of life. For example, studies have found that individuals residing in more normative living situations report a higher quality of life (13,16,17) and that those who are more depressed, but not necessarily more psychotic, rate their quality of life significantly lower (14,18). Also, even though subjective quality-of-life ratings have been linked modestly, but significantly, with objective life circumstances in some studies (17,19), few consistent associations between demographic characteristics and subjective quality-of-life ratings have been found (20). Although studies have compared quality-of-life ratings of those with and without mental illness (16), the comparisons have been quite tenuous in that the studies used different instrumentation and were conducted across samples that were neither contemporaneous nor geographically comparable.

This paper describes the quality of life of homeless persons as assessed in the course-of-homelessness study. The study compared a contemporaneously recruited sample of homeless persons with and without mental illness in terms of their objective and subjective ratings of their quality of life. We also discuss the implications of our findings for programs and providers serving homeless persons. Understanding more about the lives of homeless persons can help providers design programs that are more likely to successfully engage and retain homeless persons with mental illness.

Methods

Procedures and sampling

Most of the data reported here are from the baseline sample of the course-of-homelessness study. Subjects were drawn from two Los Angeles County sites. Persons from the downtown skid row area constituted about 85 percent of the total sample, and persons from the West Side beach area the remaining 15 percent. Homeless adults were interviewed in face-to-face structured interviews in either English or Spanish during a 13-month sampling period between October 1990 and September 1991. Informed consent was obtained, and subjects were paid $10 to complete the baseline interview.

Of the 1,782 individuals who were eligible to participate after being screened for homelessness, 1,568 (88 percent) agreed to complete the baseline interview. Thirty-five subjects with incomplete data or with marked cognitive impairment on the Folstein-McHugh Mini Mental State Examination were not included in the analyses reported here, leaving a final sample of 1,533.

People were considered homeless if they had spent at least one of the past 30 nights in a setting either defined as temporary shelter or not designed for shelter. Those whose only homeless time in the past 30 days had been spent doubled-up with family or friends were not counted as homeless. Those who had been living in their own dwelling places for less than 30 consecutive days at the time of the interview were included to avoid excluding those who were regularly homeless for a portion of each month. These individuals represented less than 4 percent of the entire sample and consisted almost entirely of people who made erratic use of single-room-occupancy hotels or who were residing with family or friends on the night before the interview as a very short-term, makeshift arrangement that included literal homelessness within the past 30 days.

The study used a probability sampling method that combined elements of Burnam and Koegel's service-setting sampling approach (21) and Rossi's "blitz" sampling approach (22). Subjects were selected at random from homeless shelters and meal facilities and from homeless populations on the streets. People were interviewed in meal facilities around meal times, at shelters in the evenings, and on the streets at night. To prepare for the sampling, we counted all the shelter beds, users of meal facilities, and homeless persons on the streets in the Los Angeles downtown and West Side areas. The size of this homeless population was assessed by a one-night count of homeless persons.

Once these parameters were determined, a sampling strategy was developed that allowed us to randomly choose subjects across three nested sampling strata proportionate to the distribution of the homeless population. The sampling strata were the population using shelter beds, the population using meal facilities but not shelter beds, and the unsheltered population using neither. Individual homeless persons were then randomly selected from each of these strata. A more detailed description of the probability sampling plan has been published elsewhere (23).

For analysis, data were weighted by the reciprocal of an estimated probability of selecting each sampled individual. Probabilities were estimated using two different underlying stochastic models that were conceived as bounds on actual probabilities. One assumed that individuals repeatedly go to the same facilities and street locations over time, and the other assumed that individuals choose randomly among geographically available facilities and street locations. Probabilities estimated under each model included two components: the selection of facilities and street locations on any given day or night of survey sampling and the selection of individuals within locations, given the selection of facility or location. Weights used in this study averaged the results from these two models (23).

Longitudinal panel

A panel of 520 persons from the baseline sample was followed every two months for 15 months, using an abbreviated version of the baseline interview. Subjects in the longitudinal panel completed 62 percent (between four and five) of the scheduled interviews; 488 subjects (94 percent) completed at least one follow-up interview. Subjects were considered to have become housed if for at least 31 consecutive days, they lived in housing they purchased themselves.

Diagnostic categories

Psychiatric diagnoses were assigned at baseline through the use of selected sections of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS), version III-R, a highly structured instrument that yields both lifetime and current diagnoses based on DSM-III-R criteria (24). The sections used were schizophrenia, depression and dysthymia, mania, alcohol dependence, and drug dependence. Using data from the DIS, we created a "chronic mental illness" category. This category, described in more detail in our earlier work (25), included all subjects with a lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia who reported having at least one symptom in the past three years and all subjects with a lifetime diagnosis of major affective disorder, excluding those with single depressive or manic episodes, those with dysthymia only, those who did not meet DIS severity criteria, and those with no symptoms in the past three years. The chronic mental illness category included only those who met criteria for these disorders.

Service use history was not included in the operationalization of the chronic mental illness category. Within the chronic mental illness group, 80 subjects (26 percent) met criteria for schizophrenia, and 233 subjects suffered primarily from affective disorders, mostly major depression. About 204 subjects (64 percent) were currently in treatment for a mental disorder. Approximately 163 (51 percent) had a dual diagnosis of a substance dependence disorder of recent onset. Detailed information about mental health status and service use has been reported elsewhere (26).

Quality-of-life ratings

Quality-of-life ratings included both objective and subjective measures. A person's monthly income is an example of an assessment of objective quality of life. An assessment of subjective quality of life measures how satisfied the person is with that income. Objective measures assessed in this study were income and benefit status, amount of time spent in shelters or other places meant for sleeping, and self-report of victimization, including physical assault, sexual assault, and robbery. Subsistence difficulty was assessed using a five-item scale (internal reliability=.85) that included questions about difficulty finding shelter, food, clothes, and a bathroom.

Physical functioning was measured using selected items from the 36-item short form (SF-36) (27) from the Medical Outcomes Survey. Instrumental functioning was assessed using a scale that asks subjects if they are able to perform six activities on their own—manage money, fill out an application, take medications as prescribed, use public transportation, arrange a job interview by phone, and find an attorney.

Subjective quality-of-life measures were modeled after Lehman's Quality of Life Interview (9), which uses the delighted-terrible scale, a 7-point scale in which 1 indicates extreme dissatisfaction and 8 indicates extreme satisfaction. Subjects were asked about satisfaction with their lives in eight different domains, five of which we describe in this paper: housing (nine items; internal reliability [alpha] of .89), health (two items; alpha=.82), finances (two items; alpha=.91), clothing (three items; alpha=.80), and food (two items; alpha=.63). For this analysis, mean scale scores were calculated for each domain separately, and all 19 items were combined into a single global quality-of-life score. This report includes only baseline quality-of-life ratings.

Analysis plan

The 319 subjects meeting the definition of chronic mental illness were compared with the 1,214 other homeless subjects, using chi square tests for categorical variables and the method of least squares to fit weighted regression models for continuous variables. To examine subjective quality-of-life measures, we first conducted a series of multiple regressions using the subjective quality-of-life measures as dependent variables and identified significant covariates among all demographic variables and objective quality-of-life variables.

Significant covariates were then grouped into enduring personal characteristics—race, age, education, and gender—and potentially modifiable characteristics—income, amount of time spent in places meant for sleeping, and depressive symptoms. Using analysis of covariance, we then compared three sets of subjective quality-of-life ratings across the two homeless samples: unadjusted ratings, ratings adjusted by enduring personal characteristics, and ratings adjusted by both enduring characteristics and potentially modifiable characteristics. Weights were included in all analyses.

Results

The sample sizes reported in the tables and text are unweighted data; however, all associated inferential analyses and percentages were conducted using the appropriate weights. Our sample of 1,533 subjects consisted of young, mostly unmarried men who were predominantly African American. The mean±SD age of the sample was 39±10 years, with a range from 19 to 90 years. A total of 575 subjects (40 percent) completed high school, and 489 (31 percent) had at least some college education.

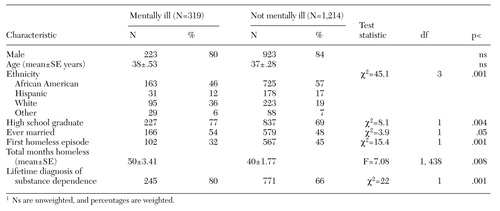

As Table 1 shows, homeless persons with mental illness were significantly more likely to be white, to be high school graduates, to have a lifetime diagnosis of substance dependence, and to have been married. Homeless persons with mental illness were less likely to be in their first episode of homelessness, and they spent more total months homeless, indicating a cyclic pattern of homelessness. During the course of the longitudinal study, 207 of the 319 mentally ill subjects (65 percent) became housed, compared with 614 (51 percent) of the homeless subjects who were not mentally ill.

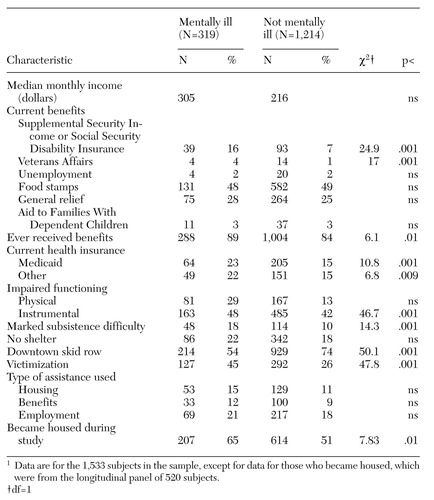

As shown in Table 2, homeless persons with mental illness had a higher median monthly income. The two groups were equally likely to receive most benefits, such as Aid to Families With Dependent Children, general relief, food stamps, or unemployment benefits. However, homeless persons with mental illness were significantly more likely to receive Supplemental Security Income and VA benefits or to have health insurance. Homeless persons with mental illness fared worse in that they reported significantly more subsistence difficulty, poorer physical functioning, and more instances of victimization.

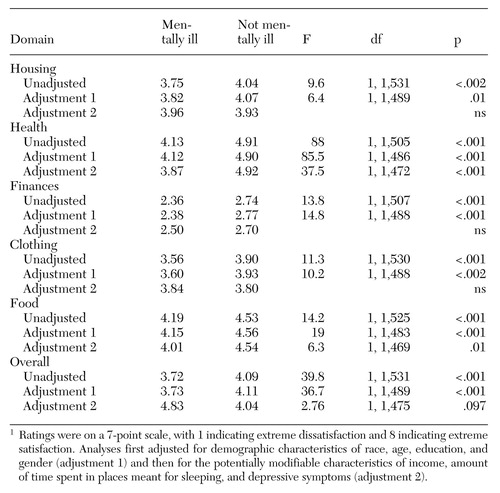

Table 3 shows subjective quality-of-life measures for the two groups. In all domains, homeless persons with mental illness rated their quality of life poorer than those without mental illness. Homeless persons with mental illness expressed stronger dissatisfaction with their finances, clothing, and housing. Differences in satisfaction between the two groups persisted even after analyses adjusted for differences in enduring personal characteristics. However, when the analyses adjusted for modifiable factors, no differences were apparent between the groups in the domains of finances, clothing, and housing.

Discussion

Of the many subpopulations in the contemporary homeless population, few have aroused more concern than those with mental illness. Consequently, over the past 25 years numerous programs have been developed to meet the needs of this homeless group. Our findings suggest that in certain ways these programs may be successful in helping persons with mental illness to become housed, and that they may be especially helpful for this group compared with homeless persons without mental illness. However, this study and others suggest that persons with mental illness may cycle in and out of homelessness more often (28,29). To address this pattern, providers should emphasize programs that ensure not only that mentally ill persons obtain housing but also that their housing situations are stable and durable over time (28).

In this study, homeless subjects with mental illness fared reasonably well in terms of income, entitlements, and health insurance, but they were more likely than homeless individuals without mental illness to experience problems with victimization, subsistence needs, and physical health. Further, the factors that explained most of the variance in the subjective ratings were potentially modifiable, such as income, time spent in places meant for sleeping, and depressive symptoms, rather than enduring personal characteristics. This finding suggests that it might be possible to improve subjective quality of life through interventions.

Even though persons with mental illness were more likely to have health insurance than other homeless individuals, they reported significantly poorer physical functioning and more dissatisfaction with health status. Although homelessness increases the risk for certain physical health problems, such as pedal edema and abrasions, cuts, and rashes (30,31,32), evidence is accumulating that persons with mental illness (33,34), and in particular homeless persons with mental illness (32,35), suffer from more physical health problems, both acute and chronic. Even when individuals have Medicaid benefits, accessibility to health care remains problematic (36), and resources available in most physical health programs for the homeless population are strikingly inadequate (37).

Further, almost one in five persons with mental illness reported marked subsistence difficulty—that is, problems finding adequate shelter, food, and clothing. Only one in 11 of those without mental illness reported marked difficulty in this area. In our study, homeless persons with mental illness were more likely to get their food from garbage cans or dumpsters. Moreover, when homeless persons experience high levels of subsistence difficulties, their subsistence needs generally demand their full attention and hinder them from seeking help for other needs, such as mental health treatment (38). To minimize this barrier, programs assisting the mentally ill homeless population might consider providing food and clothing directly to their clients.

Like other researchers (12), we found that homeless persons with mental illness were at much higher risk for victimization. Almost half of the sample with mental illness reported having been physically assaulted, sexually assaulted, or robbed in the past month. Among the 63 women with mental illness in our sample, 40 (57 percent) reported such victimization over the past month, compared with 87 (42 percent) of the men with mental illness (χ2=4.41, df=1, p<.03). These findings suggest that homeless persons with mental illness would benefit from programs providing training to maximize personal safety.

Finally, the stereotype of the homeless person with schizophrenia talking to himself on the corner does not represent the mainstream of homeless persons with mental illness. Significantly more homeless persons suffer from severe affective disorders than from chronic psychotic disorders. Although diagnosing major depression among homeless persons presents problems (38), our study suggests that a provider's index of suspicion for depression should be high when evaluating homeless individuals. If depressive symptoms are indeed modifiable, then our study further suggests that effective treatment of depression could substantially improve the subjective quality of life of homeless persons with mental illness.

Despite the strengths of its design, this study has limitations. Because it was conducted entirely in Los Angeles, we do not know the generalizability of our findings. Quality of life may partly depend on the services available locally. Indeed, two covariates strongly associated with subjective quality-of-life ratings—income and the amount of time spent in places meant for sleeping—could have been influenced by the availability and accessibility of shelters as well as the aggressiveness of outreach efforts to homeless persons.

Also, because of cost and time constraints, we used the DIS as our diagnostic tool rather than a clinical diagnostic instrument. We made every effort to maximize the validity of the DIS diagnoses by extensively training interviewers. Even though the DIS has been found to be more reliable when used in populations with a higher prevalence of mental disorders (39,40), such as the homeless population, some measurement error related to clinical diagnostic instruments is inevitable (41). Further, subjective quality-of-life ratings have been found to be strongly related to depression. Untangling the effects of mood from overall life satisfaction was not possible using our measurement approach. Therefore, it is unclear to what extent effective treatment of depression would change subjective quality-of-life ratings.

Conclusions

Homelessness continues to be a serious social and health problem, particularly among persons with mental illness. Programs addressing the needs of homeless persons with mental illness may be most successful at improving quality of life and well-being if they emphasize the maintenance of stable housing as well as the provision of services to meet subsistence needs and physical health care services. Training to maximize personal safety is especially needed, and strategies to reduce depressive symptoms might also prove effective.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant RO1-MH-64121 from the National Institute of Mental Health through Rand, by the Centers for Mental Healthcare Research at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and by the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of Veterans Integrated Service Network 16. The authors thank Mary Ann Creemer and Stacy Fortney.

Dr. Sullivan is director of the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of the Veterans Integrated Service Network 16, 2200 Fort Roots Drive, Building 58, Room 134 (16M), North Little Rock, Arkansas 72114 (e-mail, [email protected]). She is also associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. Dr. Burnam and Dr. Koegel are senior scientists in the health program at Rand in Santa Monica, California. Ms. Hollenberg is a programmer in the department of psychiatry at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 1,533 homeless subjects, by whether they were or were not mentally ill1

1 Ns are unweighted, and percentages are weighted

|

Table 2. Objective quality-of-life indicators of 1,533 homeless subjects, by whether they were or were not mentally ill1

1 Data for the 1,533 subjects in the sample, except for data for those who became housed, which were from the longitudinal panel of 520 subjects

|

Table 3. Subjective quality-of-life ratings of 1,533 homeless subjects, by whether they were or were not mentally ill1

1 Ratings were on a 7-point scale, with 1 indicating extreme dissatisfaction and 8 indicating extreme satisfactionAnalyses first adjusted for demographic characteristics of race, age, education, and gender (adjustment 1) and then for the potentially modifiable characteristics of income, amount of time spent in places meant for sleeping, and depressive symptoms (adjustment 2).

1. Lehman AF, Cordray DS: Prevalence of alcohol, drug, and mental disorders among the homeless: one more time. Contemporary Drug Problems 20:355-383, 1994Google Scholar

2. Burt MR, Cohen BE: America's Homeless: Numbers, Characteristics, and Programs That Serve Them. Washington, DC, Urban Institute Press, 1989Google Scholar

3. Robertson MJ: Mental disorder among homeless persons in the United States: an overview of recent empirical literature. Administration in Mental Health 14:14-27, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Bybee D, Mowbray CT, Cohen E: Short versus longer term effectiveness of an outreach program for the homeless mentally ill. American Journal of Community Psychology 22:181-209, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Randolf F, Blasinsky M, Leginski W, et al: Creating integrated service systems for homeless persons with mental illness: the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 48:369-373, 1997Link, Google Scholar

6. Vernez G, Burnam MA, McGlynn EA, et al: Review of California's Program for the Homeless Mentally Disabled. Santa Monica, Calif, Rand, 1988Google Scholar

7. Marshall GN, Burnam MA, Koegel P, et al: Objective life circumstances and life satisfaction: results from the course of homelessness study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 37:44-58, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Spilker B: Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1996Google Scholar

9. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Andrews FM, Withey SB: Social Indicators of Well-Being. New York, Plenum, 1976Google Scholar

11. Rosenheck R, Lam JA: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381-386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

12. Lehman AF, Keman E, DeForge BR, et al: Effects of homelessness on the quality of life of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:922-926, 1995Link, Google Scholar

13. Lehman AF, Possidente S, Hawker F: The quality of life of chronic patients in a state hospital and in community residences. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:901-907, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Sullivan G, Wells KB, Leake B: Clinical factors associated with better quality of life in a seriously mentally ill population. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:794-798, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

15. Bigelow DA, McFarland BH, Olson M: Quality of life of community mental health program clients: validating a measure. Community Mental Health Journal 27:43-55, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Sullivan G, Wells KB, Leake B: Quality of life of seriously mentally ill persons in Mississippi. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:752-755, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

17. Steiner RP, Looney SW, Hall LR, et al: Quality of life and functional status among homeless men attending a day shelter in Louisville, Kentucky. Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association 93:189-195, 1995Google Scholar

18. Lehman AF: The effects of psychiatric symptoms on quality of life assessments among the chronic mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 6:143-151, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Oliver JPJ, Mohamad H: The quality of life of the chronically mentally ill: a comparison of public, private, and voluntary residential provisions. British Journal of Social Work 22:391-404, 1992Google Scholar

20. Lehman AF: Quality of life experiences of the chronically mentally ill: gender and stages of life effects. Evaluation and Program Planning 15:7-12, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Burnam MA, Koegel P: Methodology for obtaining a representative sample of homeless persons: the Los Angeles skid row study. Evaluation Review 12:117-152, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Rossi PH, Fischer GA, Willis G: The Condition of the Homeless in Chicago. Amherst, Mass, Social and Demographic Research Institute, 1986Google Scholar

23. Koegel P, Burnam MA, Morton SC: Enumerating homeless people: alternative strategies and their consequences. Evaluation Review 20:378-404, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, et al: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:381-389, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Koegel P, Burnam MA, Farr RK: The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among homeless individuals in the inner city of Los Angeles. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:1085-1092, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Koegel P, Sullivan G, Burnam A, et al: Utilization of mental health and substance abuse services among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Medical Care 37:306-317, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health status survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30:473-483, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, et al: Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a "critical time" intervention after discharge from a shelter. American Journal of Public Health 87:256-262, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Pollio DE, North CS, Thompson S, et al: Predictors of achieving stable housing in a mentally ill homeless population. Psychiatric Services 48:528-530, 1997Link, Google Scholar

30. Gelberg L, Linn LS: Assessing the physical health of homeless adults. JAMA 262:1973-1979, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Usatine RP, Gelberg L: Health care for the homeless: a family medicine perspective. American Family Physician 49:139-146, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

32. Gelberg L, Linn LS: Social and physical health of homeless adults previously treated for mental health problems. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:510-516, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

33. Dworkin RH: Pain insensitivity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:235-248, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Tsuang MT, Wollson RF, Fleming JA: Premature deaths in schizophrenia and affective disorders: an analysis of survival curves and variables affecting the shortened survival. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:979-983, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Sullivan G, Jackson C, Jinnette KJ, et al: Physical health and medical services use in the Houston homeless project. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, Washington, DC, Nov 19-22, 1998Google Scholar

36. Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S: Care denied: US residents who are unable to obtain needed medical services. American Journal of Public Health 85:341-344, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Doblin BH, Gelberg L, Freeman HE: Patient care and professional staffing patterns in McKinney Act clinics providing primary care to the homeless. JAMA 267:698-701, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Koegel P, Burnam A: Problems in the assessment of mental illness among the homeless: an empirical approach, in Homelessness: A National Perspective. Edited by Robertson MJ, Greenblat M. New York, Plenum, 1992Google Scholar

39. Burke JD: Diagnostic categorization by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS): a comparison with other methods of assessment, in Mental Disorder in the Community. New York, Guilford, 1986Google Scholar

40. Robins LN: Epidemiology: reflections on testing the validity of psychiatric interviews. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:918-924, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. North CS, Pollio DE, Thompson SJ, et al: A comparison of clinical and structured interview diagnoses in a homeless mental health clinic. Community Mental Health Journal 33:531-543, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar