An Assessment of Clinical Practice of Clozapine Therapy for Veterans

Abstract

Clozapine therapy for 2,996 patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia was examined over a five-year period in the Veterans Affairs health care system. Patients were assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS). BPRS scores, which were available for 522 patients, indicated a significant improvement, as did AIMS scores, which were available for 252 patients. Compared with individuals who showed a modest improvement, those with a more robust response to clozapine had higher initial BPRS scores and were three times more likely to have been suicidal in the month before starting clozapine therapy.

The atypical antipsychotic clozapine is known to be beneficial in the management of treatment-refractory schizophrenia (l). Use of clozapine has disadvantages, including the risk of drug-induced agranulocytosis; the need for regular, frequent blood monitoring; and relatively high up-front drug costs. However, the potential benefits of clozapine therapy are better clinical outcomes, such as reductions in global symptomatology, aggression, suicidality, and hospitalization and improvements in quality of life (2,3,4,5).

This study analyzed outcomes of clozapine therapy based on data collected over a five-year period as part of a national quality assurance protocol for management of clozapine therapy in the Veterans Affairs system. The aim was to assess the effectiveness of clozapine therapy in a large health care setting and identify clinical variables associated with a robust response to clozapine therapy.

Methods

Data for this study were collected over a five-year period from October 1, 1991, through November 11, 1996, by the VA National Clozapine Coordinating Center as part of a quality assurance protocol for clozapine therapy of patients with treatment-refractory psychosis (6,7). Baseline data on patients' demographic and clinical characteristics and psychopathology were collected by the treatment team using patient interviews and chart reviews.

Within four weeks of beginning clozapine therapy, patients' psychopathology was rated with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Involuntary movements were rated with the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS). The BPRS and AIMS were readministered quarterly for as long as the patient remained on clozapine. Clozapine dosage and titration schedules were determined by the treating physician on the basis of the patient's clinical status.

Change in psychopathology was determined by comparing the baseline BPRS score and the last available score or the score at the time of treatment termination. Each of four BPRS subscales was scored on a 7-point scale, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. The four subscales were positive symptoms- thought disorder, negative symptoms-withdrawal, hostility, and depressive-anxious symptoms. The total BPRS score is the sum of scores on all items. The change in the overall BPRS score from baseline to endpoint was examined using an analysis of variance design and chi square tests of independence. The analyses identified clinical variables associated with improvement (a 20 percent reduction in the BPRS score) and with lack of improvement (no change in or worsening of symptoms, based on the BPRS score).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 2,996 individual patients received clozapine at 168 VA facilities during the study period. The mean± SD age of the group was 44.8±10.2 years, with a range from 21 to 95 years. Most of the patients (N=2,891, or 96.5 percent) had a primary psychiatric diagnosis of schizophrenia (N=2,891), while a smaller number (N=105, or 3.5 percent) had other psychotic conditions. Nearly half of the patients (N=1,467, or 49 percent) had a history of assaultiveness to others, which was reported by the treatment team as part of a checklist. A total of 430 patients (14.4 percent) had been assaultive in the month before beginning clozapine.

Suicidal behaviors were also a substantial risk in this veteran population; 42.3 percent (N=1,267) had a history of at least one suicide attempt, and 5 percent (N=151) had made suicide attempts in the month before starting clozapine. An additional 17.5 percent (N=524) reported having considered suicide in the month before starting clozapine.

Demographic data were available for 2,488 veterans, of which there were 132 women (5.3 percent) and 2,356 men (94.7 percent).

Drug dosing and adverse effects

The mean±SD duration of clozapine therapy for all patients was 184±216 days, with a range from 56 to 1,718 days. The mean±SD clozapine dosage was 503±204 mg per day, with a range from 25 mg to 900 mg per day. At the end of the five-year study, 50 percent of the 2,996 veterans (N=1,486) had discontinued clozapine therapy.

Among the most common reasons for discontinuing clozapine were medication noncompliance (N=359, or 12 percent), poor drug response (N=235, or 7.9 percent), and administrative problems such as transfer of the patient to a care setting where clozapine was unavailable (N=233, or 7.8 percent). Cardiovascular changes such as hypotension, tachycardia, or electrocardiogram changes led to discontinuation for 42 patients (1.4 percent). Central nervous system side effects such as dizziness and sedation were associated with discontinuation for 43 patients (1.5 percent), and seizures were associated with discontinuation for 14 patients (.5 percent). Hematologic changes associated with discontinuation included neutropenia (N=61, or 2 percent), agranulocytosis (N=14, or .5 percent), and eosinophilia (N=7, or .2 percent).

Over the study period there were 38 deaths (1.3 percent of the total sample). Most deaths were due to underlying medical illness (N=29, or 1 percent), which is not surprising given the age of the veteran population and the institutional bias of VA facilities to preferentially provide services to those with disabilities. Four deaths were due to accidental injury; 11 from unclear etiology, apparently due to an acute cardiovascular event; two from agranulocytosis (.1 percent); and two by suicide (.1 percent). Agranulocytosis deaths were not causally related to any deviations in clozapine treatment or management protocols.

Therapeutic response

Mean BPRS scores for both baseline and endpoint (the last available BPRS rating) were available for 522 patients. Because this study was a quality assurance protocol and not a funded research study, the ability to collect BPRS scores and other data for all patients was somewhat limited. A total of 407 of these patients (78 percent) showed some improvement on clozapine, and 115 patients (22 percent) showed no improvement.

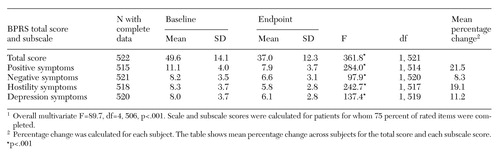

Table 1 presents patients' baseline and endpoint scores for the total BPRS and its four subscales. The mean percentage of improvement for the 407 patients who showed any improvement was 39.9 percent. A total of 301 patients (57.7 percent) showed a 20 percent or greater improvement in BPRS scores. Included in this group were 138 patients (26.4 percent) who showed at least a 40 percent improvement.

In addition, a significant improvement on the AIMS score was noted for 252 patients for whom baseline and endpoint AIMS scores were available. The mean baseline score for these patients was 5.4±7.6, and the mean endpoint score was 3±5.4 (F=50.4, df=1, 251, p<.001). Possible scores on the AIMS range from 0 to 40.

Clinical variables associated with a robust response to clozapine as indicated by improvement of at least 40 percent on the BPRS were also examined. The 138 patients who improved by at least 40 percent had higher baseline BPRS scores than the 269 patients who improved less than 40 percent (F=593.8, df=1, 405, p<.001) and were 3.01 times more likely to have been suicidal in the month before beginning clozapine treatment (χ2=5.2, df=1, p=.023).

Discussion and conclusions

As in previous reports involving both nonveteran and veteran patients, we found that patients with treatment-refractory illness improved on clozapine therapy. The study is limited by the incomplete database and its retrospective, open-label design, including the lack of a control group and possible differences in interrater assessments. Although findings must be interpreted with caution, some observations on the "real-world" use of clozapine within a large public health care system may be made.

The clozapine dosage in this sample of veterans with primary psychosis was approximately 500 mg per day. Reasons for clozapine discontinuation were primarily noncompliance, lack of clinical response, and administrative factors. Reasons for discontinuation appear to be similar for veterans across the age spectrum (8).

Of the 522 veterans for whom BPRS scoring data were available, 57.7 percent had at least a 20 percent improvement in BPRS score. Individuals with the most robust clozapine response—at least a 40 percent improvement in BPRS score—were those with higher baseline BPRS scores. Patients showed significant improvement on the four subscales of positive, negative, hostile, and depressive symptoms. Other studies of clozapine have found clinically significant improvement among 30 percent to 60 percent of patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia (1,3,9).

Only two of the 2,996 patients with refractory schizophrenia in this sample committed suicide. This finding is somewhat surprising given the severity of illness and the high proportion of suicidal thoughts and behaviors seen in this population before clozapine therapy. In a recent epidemiologic study that assessed mortality rates among more than 60,000 clozapine users, mortality was lower during periods of clozapine use than during periods of nonuse, apparently because of reduced incidence of suicide (10). In our study, individuals with the most robust response to clozapine were more likely to have been suicidal in the month before beginning clozapine. Although it is possible that not all suicides were reported, most veterans tend to use the VA care system on a long-term basis and frequently establish alliances with providers and treatment teams. This is particularly true for clozapine-treated patients, who present weekly for blood testing, as was required during the study period.

A decrease in hostility was also seen in this sample of veterans. Volavka and associates (4) have reported that clozapine therapy may be associated with a reduction in the number of aggressive incidents in a state hospital system.

Clozapine is an important therapeutic agent for veterans with severe treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Administrations and health care facilities that treat individuals with a high level of aggression and suicidality may particularly benefit from practices and policies that promote the appropriate use of this novel antipsychotic for severely mentally ill patients.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors thank Richard McCormick, Ph.D., for his helpful suggestions and Stephanie Visnik, M.A., for statistical assistance.

Dr. Sajatovic is affiliated with the Northcoast Behavioral Healthcare System of the Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 1708 Southpoint Drive, Cleveland, Ohio 44109, and with Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland. Dr. Bingham and Dr. Blow are with the Serious Mental Illness Treatment, Research, and Evaluation Center at the VA Health Administration in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and with Michigan State University in East Lansing. Dr. Garver is with the department of psychiatry and behavioral science at the University of Louisville School of Medicine and the Louisville VA Medical Center. Dr. Ramirez is with Case Western University School of Medicine. Mr. Ripper is with the Dallas VA Medical Center and the VA National Clozapine Coordinating Center in Dallas. Dr. Lehmann is with the VA Mental Health Strategic Healthcare Group at the VA central office in Washington, D.C., and Georgetown University School of Medicine.

|

Table 1. Changes in scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) for 522 veterans with treatment-refractory schizophrenia taking clozapine1

1. Kane JM, Honigfeld JG, Singer J, et al: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:789-796, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Baldessarini RJ, Frankenburg FR: Clozapine: a novel antipsychotic agent. New England Journal of Medicine 324:746-753, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, et al: A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 337:809-815, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Volavka J, Zito JM, Vitrai J, et al: Clozapine effects on hostility and aggression in schizophrenia (ltr). Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 13:287-289, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Meltzer HY, Okayli G: Reduction of suicidality during clozapine treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: impact of risk-benefit assessment. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:183-190, 1995Link, Google Scholar

6. Patient Management Protocol for Clozapine. VHA Circular 10-91-099. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 1991Google Scholar

7. Patient Management Protocol for the Use of Clozapine. VHA Directive 10-95-071. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 1995Google Scholar

8. Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF, Garver D, et al: Clozapine therapy for older veterans. Psychiatric Services 49:340-344, 1998Link, Google Scholar

9. Breier A, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, et al: Effects of clozapine on positive and negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:20-26, 1994Link, Google Scholar

10. Walker AM, Lanza LL, Arellano F, et al: Mortality in current and former users of clozapine. Epidemiology 8:671-677, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar