Emergency Psychiatry: Acute Psychopharmacological Management of the Aggressive Psychotic Patient

Management of the acutely aggressive psychotic patient is a common task in the psychiatric emergency service. Findings from the Epidemologic Catchment Area study, which investigated the prevalence of mental illness in the United States, suggested that patients with serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder are two to 15 times more likely to report violent behavior than people with no mental illness (1).

This column briefly reviews the neurobiology of aggression and recent findings about the effects of medication noncompliance among patients with severe mental illness. It discusses the advantages and disadvantages of two effective pharmacological interventions for the acute treatment of the aggressive psychotic patient.

Neurobiology of aggression

The neurobiology of impulsive aggression is the subject of an evolving science that is working toward identifying the medication or combination of medications that will most benefit the violent psychiatric patient (2). Studies using both animal and human models of violent behavior suggest that impulsive aggression involves a complex interaction of neurotransmitter and hormonal activity, societal factors, and individual personality (3,4).

Among neurotransmitters, serotonin plays a major inhibitory role in aggressive behavior. Low cerebrospinal fluid levels of 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid (5-HIAA), a major metabolite of serotonin, are significantly correlated with hyperresponsiveness to aversive stimuli and impulsive aggression but not premeditated violence (3). Dopamine and norepinephrine abnormalities may play a role in a patient's vulnerability to aggressive episodes. Animal studies indicate that increasing brain dopamine and norepinephrine activity significantly enhances the likelihood that the animal will respond to the environment in an impulsively violent manner (3).

Atypical antipsychotic medications, which affect both serotonin and dopamine activity, may have primary antihostility properties that the traditional antipsychotic medications lack (5). Several studies have supported the effectiveness of the atypical antipsychotics in the intermediate to long-term management of the violent and psychotic patient (5). In a double-blind study, clozapine and risperidone, both atypical antipsychotics, were found to have a significantly greater primary antihostility effect than haloperidol and placebo (6).

Medication noncompliance

A recent study found that patients with severe mental illness who were noncompliant with their medication regimen have a significantly increased risk of being seriously violent in their community, even after the analysis controlled for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (7). In a review of several studies of medication compliance in psychiatric treatment, patients receiving antipsychotic medication took an average of 58 percent of the recommended amount of the medications, with a range among the studies of 24 to 90 percent (8).

The best predictors of compliance may be the patient's satisfaction with the medication and acceptance of the need for treatment (7). Poor compliance has been noted among patients who suffer adverse medication side effects and who have complex treatment regimens (8).

Most patients have probably come to prefer the newer antipsychotic medications, which are associated with a lower rate of extrapyramidal side effects, compared with traditional antipsychotics (9), although emergency psychiatrists and nurses may still prefer the powerfully sedating traditional antipsychotics such as haloperidol or droperidol for acute treatment of violent patients. A discrepancy between the therapeutic medications patients prefer and those selected by emergency caregivers may undercut compliance. Poor compliance with antipsychotic medication may also be related to the patient's experience in being introduced to the drug. If emergency service staff forcibly administer a neuroleptic medication intramuscularly, the patient may become traumatized, and the patient's short- and long-term compliance may be diminished (10).

Pharmacologic approaches

The acute management of the violent and psychotic patient is referred to as rapid tranquilization. The goal is sedation, not the rapid remission of psychosis. The antipsychotic action of a neuroleptic medication takes an average of one to three weeks to produce results.

Interestingly, the two pharmacologic approaches for treatment of the aggressive psychotic patient that will be discussed here have informal names that suggest ways to serve alcoholic beverages—the "cocktail" approach and the "chaser" approach. The cocktail approach, in which two or more medications are given at about the same time, is used by approximately 55 percent of medical directors of psychiatric emergency services (11). The chaser approach, in which one medication is given in repeated doses if necessary and followed later by a second medication, is used by approximately 15 percent of medical directors. A variety of other medication regimens are used by the remaining 30 percent.

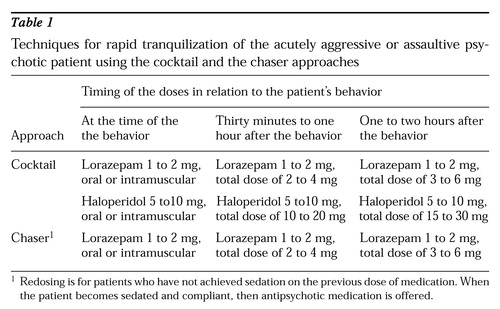

These medication techniques are usually employed after the patient has received a medical examination and no contraindications for the use of psychotropic medication have been found. The doses described in this article are for robust adults (see Table 1). Lower doses and longer delays between doses might be required for children, elderly patients, and medically compromised patients. Studies have found that both approaches have acute antiaggressive effects within approximately 30 minutes of medication administration (12,13).

Both the cocktail and the chaser approaches use the benzodiazepine lorazepam because its effects have a relatively quick onset and because it can be administered either orally or intramuscularly. Lorazepam should be given only orally or intramuscularly in the psychiatric emergency setting. Intravenous administration, particularly if used for patients with pulmonary conditions, can cause respiratory depression. In addition, although the incidence of paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines is extremely low, they are nonetheless a potential adverse effect of the medication (14).

The cocktail and chaser approaches often differ in the neuroleptic that is used in combination with the benzodiazepine. The cocktail approach usually uses a traditional neuroleptic, often haloperidol. Haloperidol is chosen for two reasons. First, haloperidol has sedative properties that act synergistically with lorazepam. Second, it is available in intramuscular injection form, allowing for involuntary administration if necessary.

The chaser approach usually uses atypical neuroleptics. This approach relies on intramuscular lorazepam if involuntary administration is required for initial sedation. Because the antipsychotic medication administered later is not involved in initial sedation, the choice of antipsychotic is not limited by the availability of an intramuscular route, and both the patient and clinician can consider a much wider array of medications. After initial sedation, long-term compliance becomes the major issue in this approach, and finding an antipsychotic medication with the fewest adverse side effects is central.

The cocktail approach

In this technique both haldoperidol and lorazepam are given at about the same time either orally or intramuscularly. (Separate syringes are used if the two medications are given intramuscularly.) The medications produce a marked synergistic sedative effect that becomes clinically apparent within 30 minutes and usually lasts several hours. Usually one dose is sufficient to sedate the patient, but if it is not, the regimen can be repeated within 30 minutes to one hour. Potential adverse effects that clinicians should watch out for include acute neuroleptic-induced akathisia, which can masquerade as agitation, and acute dystonic reactions.

If akathisia occurs, the clinician may treat the patient with 1 mg of cogentin and repeat the dose in one hour if needed. In addition, the clinician should consider reducing the dosage of antipsychotic medication. The clinician may treat dystonic reactions prophylactically or once the symptoms emerge using 1 mg of cogentin. Usually a single dose of cogentin is enough to provide prophylaxis against dystonia or treat the acute condition. If the patient with acute dystonia does not respond within 30 minutes, the dose may be repeated. As in treating akathisia, the clinician should consider reducing the antipsychotic dosage.

A recommended dosing regimen for the cocktail approach, which starts the moment the patient shows aggressive or assaultive behavior, is summarized in Table 1. The following points should be considered in using this approach.

• Start elderly patients and children with haldoperidol 1 mg to 2 mg orally or intramuscularly and concomitant lorazepam .5 mg to 1 mg orally or intramuscularly.

• Start healthy adult patients with haloperidol 5 mg to 10 mg orally or intramuscularly and lorazepam 1 mg to 2 mg orally or intramuscularly.

The chaser approach

This technique uses a benzodiazepine to initially sedate the agitated patient. Repeat dosing of lorazepam—a total dose of 2 to 6 mg, in divided doses—is usually used (15). The therapeutic goal is to acutely sedate the patient using just the benzodiazepine.

Once the patient is sedated, the clinician encourages the patient to choose an antipsychotic medication. The patient is educated briefly about potential side effects of various agents, such as weight gain, sedation, tardive dyskinesia, and cognitive effects, and is allowed to select the medication. The hope is that this approach will optimize patients' acceptance of and long-term compliance with the medication they select. The chaser approach may be more consumer friendly than the cocktail approach and appears to be gaining broader acceptance (13).

A recommended dosing regimen for the chaser approach, starting from the moment the patient shows aggressive or assaultive behavior, is shown in Table 1. The following points should be considered in using this approach.

• Start elderly patients and children with lorazepam .5 mg to 1 mg orally or intramuscularly. The total acute dose for such patients should probably not exceed 2 to 4 mg.

• Start healthy adult patients with lorazepam 1 mg to 2 mg orally or intramuscularly, and repeat this dose every 30 to 60 minutes until the patient is sedated. The total dose should not exceed 4 to 6 mg in one and a half hours (15).

• Once the patient is sedated and more cooperative, the clinician should start education about choice of antipsychotic medication.

Conclusions

Both the cocktail and the chaser approaches can be clinically successful in treating the acutely aggressive psychotic patient. The cocktail approach is more commonly used and may have the advantage of one-time medication administration. However, this approach may also put the patient at a higher risk of acute extrapyramdial side effects such as acute dystonic reactions and akathisia.

The chaser approach is a relatively newer medication technique. This approach may be kinder to the patient, which could help encourage long-term antipsychotic medication compliance. The disadvantage of this approach is that it frequently requires timely redosing of the lorazepam.

The neurobiological understanding of aggressive behavior, although in its infancy, is increasing exponentially. Recent findings favor the newer atypical antipsychotics for treating the patient who displays chronic aggressive behavior. It is hoped that continued scientific advances coupled with our accumulated clinical experience will lead to improved treatment and management of the acutely disturbed psychotic patient.

Dr. Hughes, the editor of this column, is associate chief of psychiatry at the Boston Veterans Affairs Medical Center and associate professor of psychiatry at Boston University School of Medicine. Address correspondence to him at the Division of Psychiatry, VA Medical Center, 150 South Huntington Avenue, 14th Floor, 116A, Boston, Massachusetts 02136 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1.

Techniques for rapid tranquilization of the acutely aggressive or assaultive psychotic patient using the cocktail and the chaser approaches

1. Asnis GM, Kaplan ML, Hundorfean G, et al: Violence and homicidal behaviors in psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20:405-425, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bernhardt PC: Influences of serotonin and testosterone in aggression and dominance: convergence with social psychology. Current Directions in Psychological Science 6:44-48, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Kavoussi R, Armstead P, Coccaro E: The neurobiology of impulsive aggression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20:395-403, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Coccaro EF, Silverman JM, Klar HM, et al: Familial correlates of reduced central serotonergic system function in patients with personality disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:318-324, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fava M: Psychopharmacologic treatment of pathologic aggression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20:427-451, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Conacher GN: Pharmacological approaches to impulsive and aggressive behavior, in Impulsivity. Edited by Webster CD, Jackson MA. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar

7. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA: Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:226-231, 1998Google Scholar

8. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services 49:196-201, 1998Link, Google Scholar

9. Hughes D: Risk assessment: violence, in Acute Care Psychiatry: Diagnosis and Treatment. Edited by Sederer LI, Rothschild AJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1997Google Scholar

10. Reynaud M, Tracqui A, Petit G, et al: Consequences of involuntary treatment (ltr). American Journal of Psychiatry 155:450-451, 1998Link, Google Scholar

11. Binder R: Pharmacologic approaches to violence. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Toronto, May 30-June 4, 1998Google Scholar

12. Bodkin JA: Emerging uses for high-potency benzodiazepines in psychotic disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51(May suppl):41-46, 1990Google Scholar

13. Dorevitch A, Katz N, Zemishlany Z, et al: Intramuscular flunitrazepam versus intramuscular haloperidol in the emergency treatment of aggressive psychotic behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:142-144, 1999Link, Google Scholar

14. Hall RC, Zisook S: Paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 11(suppl 1):99s-104s, 1981Google Scholar

15. Hillard JR: Emergency treatment of acute psychosis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59 (suppl 1):57-60, 1998Medline, Google Scholar