Repeated Assaults by Patients in VA Hospital and Clinic Settings

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study aim was to determine the prevalence of repeated assaults on staff and other patients and characteristics of patients who commit repeated assaults in the Veterans Health Administration of the Department of Veterans Affairs. METHODS: Patients in VA medical centers and freestanding outpatient clinics who committed two or more assaults in fiscal years 1995 and 1996 were identified through a survey of facility quality or risk managers. For each repeatedly assaultive patient, structured information, including incident reports, was obtained for all assault occasions. RESULTS: A total of 153 VA facilities responded, for a response rate of 99 percent. The survey identified 8,968 incidents of repeated assault by 2,233 patients, for a mean of 4.02 assaults per patient in the two-year study period. In 92 percent of the incidents, the assaultive patient had a primary or secondary psychiatric diagnosis. The mean age of the repeat assaulters was 62 years. Ninety-eight percent of the repeat assaulters were male, and 76.6 percent were Caucasian. At least 16 percent of the assaulters, 22 percent of the patients assaulted, and 20 percent of the staff assaulted required medical attention for injuries, which, along with the number of lost work days, indicates that repeated assaults are costly. CONCLUSIONS: Repeatedly assaultive patients represent major challenges to their own safety as well as to that of other patients and staff. Identifying patients at risk for repeated assaults and developing intervention strategies is critically important for ensuring the provision of health care to the vulnerable population of assaultive patients.

Violence in the workplace, particularly in health care settings, is an ever-increasing problem in the United States. A recent report by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health found that one million workers are assaulted every year in acts of workplace violence (1). Health care workers are among those at greatest risk for nonfatal assaults. Analyses by Lynch (2) of data from the National Crime Victimization Survey found that workplace victimization was related more to tasks performed than to the demographic characteristics of the person performing the job. Routine face-to-face contact with a greater number of people increased risk.

Many health care providers come into contact with violence-prone patients every day. A mandate for the health care field is to provide safe, secure environments for treating patients while also safeguarding health care workers. The treatment and disposition of patients who perpetrate assaults are of prime concern to systems that provide medical and psychiatric care.

Results of the 1994 Bureau of Labor Statistics annual survey of occupational injuries and illnesses, which included government workers, indicated that the majority of nonfatal assaults, or 64 percent, occurred in the service sector (3). Of the assaults in the service sector, 27 percent occurred in nursing homes and 11 percent in hospitals. The source of injury in 45 percent of the incidents was a health care patient (4).

Other studies confirm that assaultive behavior is a major underreported health care problem in the United States (5,6). Reviews of studies of patient-to-staff assaults have indicated that violent patients are younger and more likely to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia (7,8,9) and that assaults are more likely to occur during the daytime hours (10). In the review by Davis (10) and in studies by Tam and colleagues (11) and Haller and Deluty (12), nursing staff were the most frequent targets of assaultive behavior. Previous studies have examined predictors of patient violence, generally against staff, including the demographic characteristics of the patients and environmental factors (9,10,13). Few studies address patient-to-patient violence, a large category of assaultive behavior in hospital and psychiatric settings.

One of the few published reports on both patient-to-patient and patient-to-staff assaults was done by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which manages one of the largest health care systems in the United States. The veterans health care system represents the broad array of health care programming in this country, comprising large metropolitan medical centers, smaller general medical centers, outpatient clinics, psychiatric facilities, and veterans' counseling centers.

An initial study of assaultive behavior in the VHA, conducted by the VA task force on the prevention and management of suicidal and assaultive behavior, found 24,219 individual incidents of assaultive behavior in 166 VA facilities in fiscal year 1991 (14). The most frequent clinical sites for assaultive behavior were psychiatric wards, where 43.1 percent of the incidents occurred; long-term-care units, with 18.5 percent of incidents; and triage sites, with 13.4 percent of incidents. The most common diagnoses for patient perpetrators were psychoses, substance abuse, and dementia.

The report of the VA task force on suicidal and assaultive behavior recommended further study of the characateristics of patients who commit multiple assaults. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of repeated assaults and the characteristics of patients who commit repeated assaults against other patients and against staff in the VA health care system.

Methods

Letters and surveys were sent to the quality or risk managers at each of the 154 Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers and freestanding VA outpatient clinics in October 1996. Respondents were asked to report on incidents occurring in all units and areas associated with the facilities, including nursing home and extended care units, domiciliary care units, and satellite and outreach clinics. Surveys were completed by representatives of 153 medical centers and outpatient clinics, for a 99 percent response rate.

The quality or risk managers identified patients treated in their locations whose records documented that they had committed two or more physical assaults in the two most recent fiscal years, 1995 and 1996. A documented physical assault was defined as one for which a hospital incident report or police report had been filed.

The respondents provided information on each patient and all assaults using a structured format. Data collected on each assault included the date, time, and location. Examples of locations included an inpatient psychiatry unit, inpatient medical or surgical unit, substance abuse unit, domiciliary, and grounds. Data on the assaultive patient's primary and secondary diagnoses at the time of the assault were also collected. The type of assault was recorded. Physical assaults included battery with a weapon, sexual assault, battery of a person without a weapon, use of a weapon with no bodily harm, and intentional destruction of property. Nonphysical assaults included specifically directed verbal threats.

Data were also collected on the job type of any staff members who were injured, the number of staff days lost, and medical intervention required. The disposition of the assaulter after the incident—for example, general psychiatric ward, specialized unit for assaultive patients, seclusion, or jail—was also recorded. In addition, the survey respondents were asked to provide the police or incident reports of all listed assaults for each patient. The diagnoses reported on the assault survey reflected clinicians' estimation of the assaultive patient's diagnoses at the time of the assault.

Computerized hospital records of the Department of Veterans Affairs were used as another source of information on the characteristics of the assaultive patients. The records included information on the patients' sex, age, race, marital status, and treatment unit. Additional diagnostic information was available for patients with an inpatient admission. Diagnostic and demographic information on repeat assaulters was compared with that for the entire VHA population for fiscal years 1995 and 1996, using data from the VA inpatient database. Data on only sex and age were available for assaultive patients who had never been inpatients, because outpatient records include only basic demographic variables and no diagnoses.

Expenditures for patient care were calculated by the VA's Allocation Resource Center in Boston, which compiles VA cost data. The expenditures for repeat assaulters were compared with the averages for "basic" patients in the VHA system as well as with the averages for "special" patients, a subgroup of patients characterized by high health care utilization and by diagnoses such as spinal cord injury or schizophrenia that require intensive services.

Data were gathered on all assault incidents for all patients who committed two or more assaults in the study period. Thus analyses are presented at the patient level in the subsection on characteristics of assaulters and at the incident level in the subsection describing incidents of assault.

Results

Characteristics of assaulters

Of the 2,233 patients in this sample, demographic data were available on 2,122 patients, or 95 percent. In fiscal years 1995 and 1996, patients who committed repeated assaults in the VA system were predominantly male (98 percent, N=2,076). They had a mean age of 62.2±14.7 years, with a range from 24 to 101 years. Racial and ethnic distribution was 76.6 percent Caucasian (N=1,548), 19.4 percent African American (N=392), and 4 percent other races (N=91); racial or ethnic group was unknown for 101 cases.

About one-third of the patients were married or widowed (34.9 percent, N=710), another third were never married (32.6 percent, N=663), and a third were divorced or separated (32.4 percent, N=658); data on marital status were missing for 45 cases. According to the survey data, 947 patients, or 42.4 percent, had a primary or secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia.

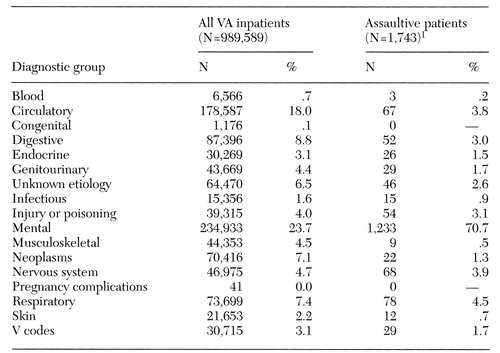

A diagnosis of some mental illness (ICD-9 codes 290 through 319) was the primary diagnosis for the first hospital stay of fiscal years 1995 and 1996 for 1,233 of the 1,743 assaultive patients with inpatient records, or 70.7 percent. Some 34.1 percent of these diagnoses (N=594) were of schizophrenia, and 5.8 percent (N= 101) were of substance use disorders. Table 1 shows the distribution of primary diagnoses among inpatients who committed repeat assaults.

In a comparison of the VHA patients who were repeat assaulters with the total VHA population of inpatients (N=989,589), no significant differences were found for gender, race, and ethnicity. Ninety-seven percent of the VHA population were male, 73 percent were Caucasian, 21 percent were African American, and 6 percent were of other races or ethnic groups. The average age of the VHA inpatient population was 59.1±14.6 years, compared with 62.2±14.7 years for the repeat assaulters. Significantly more assaultive patients had never been married (32.6 percent, compared with 12.9 percent of the VHA inpatient population), and fewer were married or widowed (34.9 percent, compared with 53.6 percent for the VHA inpatient population; χ2=747.4, df=2, p<.001).

A total of 234,933 patients, or 23.7 percent of the VHA inpatient population, had an ICD-9 diagnosis in the mental diseases category. There were significantly more assaultive patients among patients with mental diseases than among patients with primary medical diagnoses (χ2=2,117.9, df=1, p<.001).

VA statistics on medical programs provided information on the distribution of patients among treatment units (15,16). In fiscal year 1996, there were 843,938 discharges from VA medical centers. Compared with the overall VHA population, assaultive patients were more likely to be discharged from inpatient psychiatric units (47.6 percent, or 3,188 patients, compared with 20.2 percent, or 170,705 patients, for the overall VHA population). Assaultive patients were less likely to be discharged from medical or surgical units (42.2 percent, or 2,827 patients, compared with 75.5 percent, or 637,020 patients), and were more likely to be discharged from nursing homes or domiciliaries (10.1 percent, or 678 patients), compared with 4.3 percent, or 36,213 patients). Analysis showed a significant difference for the comparison of treatment settings (χ2=3,937.1, df=2, p<.001).

The two distributions were also markedly dissimilar in fiscal year 1995: 38.6 percent of assaultive patients (N=1,917) were discharged from psychiatric units, compared with 20.2 percent of the VHA population (N= 176,467); 42.8 percent of assaultive patients (N=2,122) were discharged from medical or surgical units, compared with 76.3 percent of the VHA population (N=668,020); and 18.6 percent of assaultive patients (N=921) were discharged from nursing homes or domiciliaries, compared with 3.6 percent of the VHA population (N= 31,243). Again, the difference between treatment settings was significant (χ2=4599.4, df=2, p<.001).

Patients who committed multiple assaults were heavy users of VA health care resources, as measured by cost of service. The average patient who committed at least two assaults used 27.6 times the resources of the average "basic" VA patient and two times the resources consumed by VA "special" patients, those who require high-intensity services.

Incidents of assault

A total of 8,968 incidents of repeated assault involving 2,233 patients in fiscal years 1995 and 1996 were reported, for a mean of 4.02±3.68 assaults per patient, with a range from two to 52. Eighty-three percent of the sites (N=127), with representation from all 22 VHA service regions, reported repeated assaults, and 17 percent (N=26) reported no repeated assaults. Four of the 22 service regions accounted for 40.2 percent of the assaultive patients. These four regions each have two or more long-term psychiatric hospital facilities; three of these regions are in the Northeast, and one is in the Midwest.

Psychiatric diagnoses accounted for the top nine primary diagnoses among patients who committed repeated assaults, representing 85 percent of the incidents. Altogether, in 92 percent of incidents, the assaulter had a primary or secondary psychiatric diagnosis. Forty-seven percent had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. As noted earlier, assaultive patients with inpatient discharges were more likely to be characterized by a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other mental illness than were patients in the general VA population.

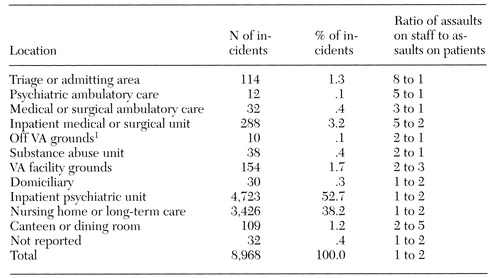

Table 2 presents the location of assault incidents and the approximate ratio between patient-to-staff assaults and patient-to-patient assaults in those locations. Approximately 53 percent of the assaults occurred on inpatient psychiatry units, and 38 percent occurred in nursing homes or long-term-care units. No other type of unit or location—medical, surgical, substance abuse, triage, ambulatory care psychiatry, or canteen—accounted for more than 4 percent of the incidents. Patient-to-patient assaults were more likely in inpatient psychiatric units, nursing homes, and domiciliary units. Patient-to-staff assaults were most common in the triage or admitting area and outpatient psychiatric units.

Patient-to-patient assault accounted for 5,959 incidents involving 1,783 patient perpetrators, an average of 3.34 assaults per perpetrator. The majority of those assaults—55 percent—occurred on inpatient psychiatry units. Ninety-five percent of these assaults, a total of 5,663, were classified as battery without a weapon. The next most common locations for patient-to-patient assault were nursing homes and long-term-care units, accounting for 40 percent of those assaults. In almost half of the incidents of patient-to-patient assault—48.4 percent—the assaulter had a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

A total of 3,024 patient-to-staff assaults were perpetrated by 1,329 patients, an average of 2.28 assaults per patient. Eighty-seven percent of the assaults on staff were classified as battery without a weapon, and 7 percent were specifically directed verbal threats. The other 5 percent were made up of intentional battery with a weapon (2 percent), sexual assault (1 percent), use of a weapon with no harm (1 percent), and destruction of property (1 percent). In 41 percent of these incidents, the assaultive patient had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. In the vast majority of patient-to-staff incidents (83 percent), nursing staff were the target of the assault.

In 66 percent of the patient-to-patient assaults (3,931 incidents), neither the victim nor the perpetrator required medical intervention. In 15 percent of the assaults (880 incidents), the assaulting patient required medical intervention for injuries, and in 22 percent (1,297 incidents), the assaulted patient required medical intervention.

Among the patient-to-staff assaults, 64 percent, or 1,942 incidents, required no medical intervention. However, in 19 percent of these assaults, or 571 incidents, the assaulting patients needed medical attention, as did staff members in 20 percent of the assaults, or 590 incidents. In 97.5 percent of patient-to-staff assaults (2,947 incidents), the assault did not result in lost work days. For the 78 incidents that led to lost work days, the median number of days lost was three, the mean±SD was 20.4±82.7 days, and the range was from one to 700 or more days. A total of 1,590 days were lost as a result of assaults in fiscal years 1995 and 1996.

In the majority of incidents (47.4 percent, or 4,752 incidents), the assaultive patients were treated on general psychiatry wards after an assault. In 21.5 percent of the incidents (1,927 assaults), the assaultive patients were treated in nursing homes. The third most common disposition was that no additional treatment was required; the assaultive patients in most of these incidents were psychiatric patients who were already located on inpatient psychiatric units or long-term nursing care units. Measures such as seclusion on the general psychiatric unit, placement in a maximum-security treatment program, or transfer to jail for confinement were used in only 4.7 percent of incidents (422 assaults).

The proportion of assaults that took place during the three work shifts—day, from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m.; evening, from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m.; and night, from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m.—were calculated. Forty-four percent of the assaults occurred on the day shift, 35 percent on the evening shift, and 21 percent at night, a significant difference (χ2=1,748.2, df=2, p<.001).

Discussion

This study documented 8,968 assaults perpetrated by 2,233 repeat assaulters in a two-year period (fiscal years 1995 and 1996). Patients who committed repeat assaults were characterized by psychiatric diagnoses, mature adult age (a mean of 62 years), and high health care costs. Substance abuse diagnoses were not common in relation to the incidence of these diagnoses in the general VHA inpatient population.

The strengths of the study include the high response rate, from 99 percent of VHA facilities, combined with complete coverage of the health care system under study, use of collateral information from police and hospital incident reports, and use of additional patient databases to supplement the survey material.

This study provides a unique perspective on the issue of patient violence because the focus is on the most assaultive, difficult-to-treat patients for any health care system. Without adequate methods to identify and control potentially violent situations, health care providers are faced with the issue of how and where to provide appropriate treatment for patients who have previously perpetrated assaults and are at risk for further aggression. Data from this study provide a first step in the understanding of a clinically complex population and politically charged problem.

In agreement with earlier studies, including those in non-VHA settings, this study found that most assaults occurred during the day shift, that repeat assaulters commonly had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and that nursing staff were typically the targets in assaults on staff members (7,8,9). The average age of the repeat assaulters in this study differs from reports in the literature that violent patients are typically younger (7,8,9). This difference may be a reflection of differences between the patient population served by the VHA, which is overall an older population, and those served in other health care settings.

Most assaults occurred on inpatient psychiatric units or nursing home or long-term care units. Most of the assaulters were treated on these units after the assault, suggesting they were already on the unit best suited to handling them. From a clinical perspective, maintaining assaultive patients on their regular treatment units may well optimize continuity of care; thus no change in this part of the process is recommended. Other treatment alternatives such as seclusion, placement in specialized units for assaultive patients, or jail, were rarely used. The lack of available specialized units may be the reason there are few dispositions to these units, while incarceration in a jail or maximum-security facility can be regarded only as a last-resort measure. However, the nature and effectiveness of specialized units should be investigated to determine the best use of scare health care dollars.

The frequency of assaults in nursing home and long-term-care units may reflect the trend toward increasing assaults by older patients that Tardiff (8), Haller and colleagues (17), and Kalunian and colleagues (18) observed. The long-term outcomes for seriously mentally ill patients who are being treated with atypical antipsychotic medications and specialized intervention programs warrant further research. The need to understand both the risks for this vulnerable population and the threat from them will increase as the general population ages and the numbers of patients in long-term facilities and congregate housing arrangements increase. Thus a comprehensive assessment of the extent of the repeat-assault problem in the non-VHA sector is warranted.

Although medical attention and days off work were not usually required for assault victims, assaults nonetheless impose costs on the system of care. Future research should focus on the outcomes of targeted staff training in how to recognize early signs of aggressiveness and implement intervention strategies to minimize the escalation of violence among assault-prone patients.

Conclusions

A specific focus on the humane, appropriate treatment for the most violent, aggressive patients in any health care system—those who are repeatedly assaultive—can yield positive returns in terms of patient care, health care providers' safety, and health care utilization and costs. Facilities may benefit from approaching the problem of patients who commit repeat assaults from two perspectives: intervention training for staff and targeted interventions for at-risk patients.

Assaultive behavior can be fiscally, emotionally, and physically costly. Health care systems—especially those with psychiatric and long-term-care facilities—will need assistance in developing innovative methods to deal with repeatedly assaultive patients. Research focused on methods and programs to reduce the likelihood of violent behavior among patients is the necessary next step in minimizing repeat assaults in health care settings.

Dr. Blow is director, Dr. Barry is associate research scientist, Ms. Copeland is a data analyst and programmer, and Ms. Ullman is a program evaluator at the Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center of the Department of Veterans Affairs and the department of psychiatry at the University of Michigan. Dr. McCormick is chief of the psychology service at the Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Dr. Lehmann is associate director for psychiatry in the mental health strategic healthcare group at the headquarters of the Department of Veterans Affairs in Washington, D.C. Address correspondence to Dr. Blow at the Veterans Affairs Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center, P.O. Box 130170, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48113 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. ICD-9 diagnostic groups for primary diagnoses at first discharge of the total population of inpatients treated in Veterans Affairs (VA) health care facilities and of patients who committed repeated assaults in fiscal years 1995 and 1996

1Does not include outpatients. A total of 490 assaultive patients did not have inpatient records in fiscal years 1995 and 1996.

|

Table 2. Location of incidents of assault within VA health care facilities in fiscal years 1995 and 1996 and ratio of assaults on staff to assaults on patients

1Treatment related field trips off VA grounds

1. US Department of Health and Human Services: Violence in the Workplace: Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies. Pub 96-100. Cincinnati, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Publications Dissemination, 1996Google Scholar

2. Lynch JP: Routine activity and victimization at work. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 3:283-300, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Annual Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses. Washington, DC, US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1994Google Scholar

4. Work Injuries and Illnesses by Selected Characteristics, 1992. Pub USDL-95-288. Washington, DC, US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1994Google Scholar

5. Lion J, Reid W: Assaults Within Psychiatric Facilities. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1987Google Scholar

6. Appelbaum PS, Dimieri RJ: Protecting staff from assaults by patients: OSHA steps in. Psychiatric Services 46:333-334,338, 1995Link, Google Scholar

7. Dehon K: The determinants of aggression and violence among psychiatric patients: a review. Acta Psychiatrica Belgica 93:261- 280, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

8. Tardiff K: The current state of psychiatry in the treatment of violent patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:493-499, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Aquilina C: Violence by psychiatric in-patients. Medicine, Science, and the Law 31:306-312, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Davis S. Violence by psychiatric inpatients: a review. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:585-590, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Tam E, Engelsmann F, Fugere R: Patterns of violent incidents by patients in a general hospital psychiatric facility. Psychiatric Services 47:86-88, 1996Link, Google Scholar

12. Haller RM, Deluty RH: Assaults on staff by psychiatric in-patients: a critical review. British Journal of Psychiatry 152:174-179, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Powell G, Caan W, Crowe M: What events precede violent incidents in psychiatric hospitals? British Journal of Psychiatry 165:107-112, 1994Google Scholar

14. VA Suicide and Assaultive Behavior Task Force: Report of a Survey on Assaultive Behavior in VA Health Care Facilities. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 1995Google Scholar

15. Summary of Medical Programs: October 1, 1994, through September 30, 1995. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veteran Analysis and Statistics, 1995Google Scholar

16. Summary of Medical Programs: October 1, 1995, through September 30, 1996. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veteran Analysis and Statistics, 1996Google Scholar

17. Haller E, Binder RL, McNiel DE: Violence in geriatric patients with dementia. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law 17:183-188, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

18. Kalunian DA, Binder RL, McNiel DE: Violence by geriatric patients who need psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51:340-343, 1990Medline, Google Scholar