An Ethnographic Study of the Meaning of Continuity of Care in Mental Health Services

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: As a step toward developing a standardized measure of continuity of care for mental health services research, the study sought to identify the interpersonal processes of giving and receiving day-to-day services through which individual providers create experiences of continuity for consumers. METHODS: Ethnographic methods of field observation and open-ended interviewing were used to investigate the meaning of continuity of care. Observations were carried out at two community mental health centers and a psychiatric emergency evaluation unit in Boston. Sixteen recipients and 16 providers of services at these sites were interviewed. RESULTS: Six mechanisms of continuity were identified, labeled, defined, and described through analysis of field notes and interview transcripts: pinch hitting, trouble shooting, smoothing transitions, creating flexibility, speeding the system up, and contextualizing. The mechanisms elaborate dimensions and principles of continuity cited by other observers and also suggest new formulations. CONCLUSIONS: The mechanisms identified in this study facilitate operationalization of the concept of continuity of care by specifying its meaning through empirically derived indicators. Ethnography promises to be a valuable methodological tool in constructing valid and reliable measures for use in mental health services research.

Many individuals who receive community mental health services suffer from severe conditions that are chronic and debilitating. The phrase "continuity of care" generally refers to the management and treatment of these conditions over time. Its importance for community mental health services is undisputed and has gained renewed attention in light of managed care's increased emphasis on organizing services as a continuum—a system of interventions with multiple components of varying intensity (1). Thus it is not surprising that continuity of care has been designated the "strategic first choice" for the development of measures of service functioning (2).

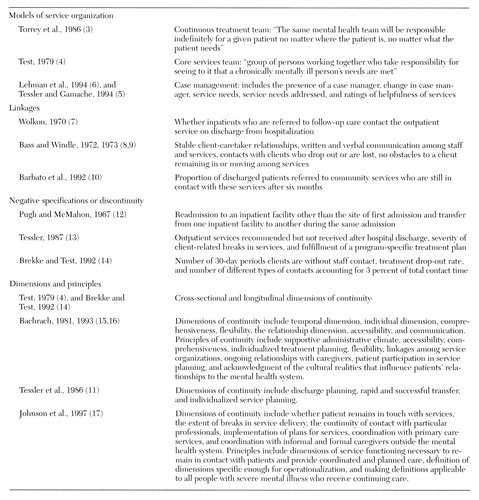

Many attempts to conceptualize continuity of care have been described in the research literature. The results are summarized in Table 1. Some conceptualizations focus on a particular model of service, such as the continuous treatment team or case management (3,4,5,6), while others emphasize linkages (7,8,9,10). Because, as one team of investigators pointed out, discontinuity is more easily measured than continuity (11), several conceptualizations are framed in negative terms, resulting in attempts to assess gaps, lags, and interruptions in the system of care (11,12,13,14). Continuity of care is frequently conceptualized as being cross-sectional and longitudinal (4,14,15,16), but these dimensions are too broad or general to be helpful in developing standardized measures. More specific dimensions, such as accessibility, communication, and individualized service planning, characterize the most detailed conceptualizations (11,15,16,17).

Existing conceptualizations of continuity of care have been faulted for being vague, inconsistent, and overinclusive and therefore difficult to operationalize for measurement purposes (11,17). As a result, assessment efforts have been diverse, indirect, and brief. Above all, existing measures are far removed from the day-to-day activities in which continuity of care is enacted by individual caregivers and their clients.

The ultimate objective of the research described in this paper is to produce a standardized measure of continuity of care for use in mental health services research. The measure is intended as a structured interview for use with recipients of mental health services, especially persons with severe and persistent mental illness. The goal of the first phase, reported here, was to use ethnography to construct a detailed definition of continuity—building on previous efforts—through systematic field research.

Methods

Ethnography is a research method traditionally used by anthropologists to investigate unfamiliar cultures (18,19). The method now serves many other purposes (20,21). Typically, ethnographic data are collected through participant observation and open-ended interviewing. Participant observation consists of spending time and talking with people in their own settings. Open-ended interviews are frequently organized in terms of topics rather than questions. Both techniques are characterized by an iterative process: repeated reformulation and investigation of new research questions that arise from the answers to previous questions.

Among other things, ethnography elicits and represents "insider points of view" (22), insiders being the "subjects" of study. Representation takes the form of explaining the meanings that insiders ascribe to their experiences—the ways they make sense of the world (23).

Analysis in ethnography therefore consists of the interpretation and articulation of insider meanings. Meanings are interpreted by identifying themes in the data, constructing categories, and comparing information from different sources. Meanings are articulated through description: elaborating general statements through examples, laying out particular logics, and incorporating multiple perspectives. Often preliminary understandings are presented to study participants for corroboration, elaboration, and critique. This practice reflects the fact that in ethnography, research "subjects" are defined as expert informants.

Study design

An ethnographic study investigating the meaning of continuity of care for persons who receive publicly supported mental health services was carried out over approximately one year in 1996-1997. Two participant groups and three community service sites were included in the study design. The participant groups were recipients and providers of mental health services. Field sites were two public community mental health centers (CMHCs) and one emergency psychiatric evaluation unit in Boston.

Study participants

The participants in the ethnographic study were 32 adults who completed research interviews and agreed to the observation process. They represented 16 recipients and 16 providers of mental health services at the three field sites.

The 16 recipient or client interviewees responded independently to notices posted at four CMHC locations or were referred through clinicians. Every client who volunteered was interviewed. The group consisted of four men and 12 women. Four were African American, two were Latino, and ten were white. Diagnoses, determined through self-report, included schizophrenia for seven clients, major depression for four clients, bipolar disorder for four clients, and schizoaffective disorder for one client.

The 16 provider interviewees were approached individually with a request for an interview. No provider who was asked for an interview refused. Most provider interviewees had no one-to-one relationship with client participants, although some were members of clinical teams who followed the clients who were our informants.

The provider group also consisted of four men and 12 women. Four were African American, and 12 were white. Provider interviewees were selected to represent a variety of service functions, including case manager, therapist, physician, housing specialist, and program administrator. Almost all program administrators who participated were also involved in direct care.

Data collection

Data collection consisted of participant observation at the three field sites and interviews with study participants. Approximately 130 hours of observations were carried out. Observations at the CMHCs took place during clinical team meetings, where cases were systematically reviewed and acute problems addressed, and during meetings where housing decisions were made. A total of 75 hours of clinical team meetings and 20 hours of housing meetings were observed. Evaluations and disposition decision-making processes were observed at the psychiatric emergency unit; 38 hours of observation were carried out in that setting. Data were recorded as narrative descriptions, or field notes, immediately after each observation period.

Interviews with clients elicited the details of their personal experiences with mental health services. Topics included relationships with service providers; experiences of change such as hospitalization, discharge, departures of case managers or therapists, new medications, and new housing; perceived functions of services; and prioritization of services and service needs. Provider interviews focused on professional responsibilities and functions, perceptions of client experiences, and the meaning of continuity of care.

Thirty-two interviews ranging in length from one to one and a half hours were conducted. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Interviewees received an honorarium of $15. The interviews followed an iterative process, meaning that questions about topics and sometimes the topics themselves changed as our formulation of the meaning of continuity developed. In addition, the interviews also served as avenues to explore preliminary formulations by presenting them to interviewees and eliciting feedback.

Data analysis

Sources of data for the study consisted of field notes and interview transcripts. Data analysis proceeded according to the following steps.

We began by bringing to the narrative material a set of analytic constructs drawn from the research literature and seeking to define these constructs through concrete examples. The examples suggested revisions of the initial constructs and also new constructs, as we encountered data that seemed clearly relevant to continuity but that could not be mapped easily onto any of the pre-existing categories.

In cases where initial constructs and empirical examples could be matched, we then asked how the example worked to create continuity. This approach brought us to the description of process, or mechanisms. For examples with no matching construct, we sought to create one by asking what larger process or mechanism the example might illustrate. Combining new and revised initial constructs, we returned repeatedly to the data, seeking new examples, redefining, making adjustments, and testing the accuracy of the constructs by applying them to more examples. The same steps were used to analyze client and provider data.

Results

Results take the form of a taxonomy of mechanisms, definitions, and case illustrations. Six labeled mechanisms are presented below: "pinch hitting," "trouble shooting," smoothing transitions, creating flexibility, "speeding the system up," and contextualizing.

Pinch hitting

When individual service providers step outside their prescribed roles to undertake tasks usually performed by someone else, they engage in a process of "pinch hitting." Pinch hitting occurs when a CMHC team psychiatrist takes a throat culture for a client who has no access to primary care, when a psychiatric nurse provides postsurgical follow-up for a mentally disabled person denied at-home care, when a therapist fills out housing referral or benefit application forms in the absence of a case manager, or when team members cover for one another during illnesses and vacations. Providers may also pinch hit for clients—by seeing that their rent is paid during hospitalizations, keeping important appointments on their behalf, or even feeding the cat.

Trouble shooting

Providers "trouble shoot" for clients by anticipating potential problems and moving to address them before they develop. A case manager who avoids hospitalization by arranging respite care for a client whose condition is deteriorating is trouble shooting, as is the outpatient psychiatrist who intervenes with hospital staff to try to prevent a premature discharge. A provider committed to trouble shooting makes an effort to stay in touch with colleagues who share responsibility for an individual's care. Pinch hitting closes gaps in services; trouble shooting works to preclude them.

Smoothing transitions

Smoothing transitions also helps avoid service gaps. This mechanism has several different forms. "Keeping some things the same" for a client who is experiencing a significant change—for example, not changing providers at the same time as housing—can make a change less disruptive.

Creating overlap in services also helps to smooth transitions. Connecting a client with outpatient services before the date of discharge from a psychiatric hospitalization—for example, through a visit from the outpatient provider—is a means of creating overlap. Arranging for a client to meet a new clinician before the departure of the current caregiver builds overlap into the process of provider change. Overlap is inherent in the structure of teams patterned on the models of continuous treatment or the Program for Assertive Community Treatment, where responsibility for care is deliberately located at the level of the team to ensure consistency in the context of inevitable staff turnover (3).

Making change gradual and increasing provider contacts at times of change also help to smooth transitions. Client participants in this study stated that changing outpatient providers would be easier if incoming personnel read their records before meeting them, thereby eliminating the painful necessity of repeating life histories to each newcomer.

Creating flexibility

Adapting to meet the needs of individual clients creates flexibility, which helps to preclude gaps in services. Steps taken to make accommodations in scheduling and other aspects of services illustrate this process. Arranging appointments at convenient times and accepting drop-in meetings are ways of accommodating, as is attempting to honor client preferences for particular provider characteristics, such as gender and ethnic background. Some systems have institutionalized flexibility by mandating the use of unusual and individualized tactics such as street outreach and community treatment teams for engaging persons considered difficult to reach.

Speeding the system up

Providers work to facilitate client movement through the service system by moving to "speed the system up." They may make repeated calls to remind colleagues of their responsibility for implementing a transition for a client such as a move to better housing. By making it clear that activities are being monitored, repeated reminders can result in reordered priorities and more expeditious progress toward goals.

Practitioners also depart from standard procedures to speed the system up. They may agree to fax a document instead of mailing it, provide information over the telephone instead of waiting for the written request, or double-book appointments—all clear violations of protocol in certain service settings.

Speeding the system up cuts down on waiting time for clients and creates shortcuts to services. However, departing from standard procedures may have negative consequences, such as breaches of confidentiality, while also promoting continuity.

Contextualizing

Providers who have been acquainted with individual clients for long periods can apply their knowledge to help colleagues redefine clients' discouraging situations. Offering a historical perspective on clients' troubling behaviors or disappointing circumstances can often place them in a more positive light and preclude gaps in service that may develop when colleagues perceive that an intervention is not producing immediate results.

Thus when a young man was jeopardizing his residential placement by being consistently disruptive, an outreach worker who had known him for years pointed out that he used to be homeless and addicted to drugs. Now, although difficult to deal with at times, he was sober and able to tolerate living in a group residence. Similarly, when residents in high-intensity community housing were having trouble engaging in group therapy, a clinician who had worked with them years ago as inpatients reminded colleagues that at that time, the therapeutic goal had been simply to enable them to spend several minutes together in the same room. Now the group was not only able to tolerate physical proximity, but was beginning to interact.

In both instances, dysfunctional behaviors were recast as improvements through a reframing or contextualization process. Providers were reinvigorated after realizing that problems actually reflected positive change, and they experienced renewed commitment to trying relationships as a result.

Discussion

The series of mechanisms presented here is illustrative, not exhaustive. It represents an attempt to begin to dissect the components of continuity (17) by articulating its meanings at a particular level of service provision—the level of relationships linking clients with individuals or groups of providers. In emphasizing everyday activities that take place within these relationships, we have tried to make explicit some of the concrete processes through which caregivers construct experiences of continuity for clients. Other levels to which the concept of continuity has also been applied—for example, the program level (14)—are topics for future analyses of this kind.

The mechanisms of continuity described here reflect gaps in the service system identified by others (5,11,14). However, rather than simply serving as indicators the mechanisms point to ways gaps may be sealed, as in pinch hitting, and even precluded, as in smoothing transitions, trouble shooting, creating flexibility, and contextualizing.

In itself, ethnography stakes no claim to generalizability. In considering the study findings, however, we should ask whether the mechanisms identified and any measure based on them reflect characteristics peculiar to Boston. An effort to represent a range of possible meanings and manifestations of continuity was made in selecting field sites and interviewees. We tried to include only items promising to be maximally, if not universally, applicable in constructing the standardized research instrument.

The mechanisms also speak to several more specific dimensions and principles of continuity cited by other observers. Accommodating clients by scheduling appointments at convenient times and allowing drop-ins is one way of defining the dimension of flexibility cited by Bachrach (15,16). Because different arrangements are made with different clients, and because these arrangements are negotiated, accommodating also reflects the principles of individualized services and consumer participation in the planning and organization of care (16). Speeding the system up helps to ensure that plans for services are actually implemented (16).

Accommodating and contextualizing both grease the wheels of relationship between individual clients and providers. Accommodating helps keep clients engaged with their caregivers by enabling them to exercise some control. Contextualizing helps keep providers engaged by reminding them that growth and development are possible for even the most severely disabled individuals. Because both mechanisms work to sustain the provider-client relationship, they address the dimensions of continuity in contacts with particular providers (16,17).

New formulations of existing dimensions are also suggested by the mechanisms. Smoothing transitions by lacing change with consistency ("keeping some things the same"), by creating overlap in relationships with providers, and by making change gradual are not simply longitudinal processes invoking the temporal dimension of continuity of care (4,14,15,16). They also require attention to timing. Efforts to speed the system up also implicitly acknowledge the importance of appropriate timing, as they represent attempts to connect clients with particular services at the moment they both need them and are willing to accept them. Timing, as part of the longitudinal dimension, merits sustained examination as we continue to elaborate the concept of continuity of care.

The mechanisms reconfirm the essential role of clinicians and other direct care staff in creating continuity for clients and allow us to glimpse some of the actual practices through which this process takes place. These practices are neither mysterious nor esoteric. Mostly, they reflect skills that are well within the capabilities of trained clinicians and activities that are consistent with the day-to-day routines of service provision.

However, these skills cannot be exercised or the necessary activities carried out without structural compatibility at the program level and the service-system level. Provider participants in this ethnographic study succeeded in implementing mechanisms of continuity because the environments in which they worked made it possible. For example, weekly team meetings created the conditions for trouble shooting by bringing staff together to exchange information in a timely and systematic way.

Recognizing the role of structural compatibility refocuses attention on the importance of continuity at the service-organization level as well as at the interpersonal level. More important, it reminds us that these levels are interdependent. Each must reinforce the other for effective continuity of care to take place.

Conclusions

Investigators working to improve the definition and measurement of continuity of care have argued that more readily operationalizable constructs and improved coordination of research efforts are essential if significant progress is to be made (17). This study speaks to both needs.

Mechanisms of continuity specify the meanings of more general principles and dimensions. Thus they facilitate operationalization by providing empirically defined indicators from which interview items may be derived. Some of the mechanisms described here specify the dimensions and principles developed by Bachrach (15,16), suggesting that these dimensions may not be as difficult to operationalize as they appear (17) and showing how current research can follow from and build constructively on previous work.

Specification brings with it certain dangers, however. Readers may object to details of our categorization or disapprove of particular actions described. The intent is not to reach universal agreement on the characterization or appropriateness of the mechanisms. Rather, it is to demonstrate that broad concepts of continuity of care can be made more operationalizable by making their meanings more concrete.

The mechanisms serving as the means to this end are products of an ethnographic study. They are being used as the basis for developing domains, indicators, and items for a structured research interview to assess continuity of care. The results suggest that ethnography will prove a valuable methodological tool in future efforts to construct measures for use in mental health services research.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant 1RO1-MH-54733 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Ann Hohmann, Ph.D., M.P.H., for her comments.

Dr. Ware and Ms. Tugenberg are affiliated with the department of social medicine at Harvard Medical School, 641 Huntington Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02115 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Dickey is with the department of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Dr. McHorney is with the departments of preventive medicine and medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Medical School.

|

Table 1. Conceptualizations and operationalizations of continuity of care

1. Schreter RK, Sharfstein SS, Schreter CA: Managing Care, Not Dollars: The Continuum of Mental Health Services. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

2. Eaton WW: Strategies of measurement and analysis, in Mental Health Service Evaluation. Edited by Knudsen HC, Thornicroft G. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1996Google Scholar

3. Torrey EF: Continuous treatment teams in the care of the chronic mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:1243- 1247, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Test MA: Continuity of care in community treatment. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 2:15-23, 1979Google Scholar

5. Tessler R, Gamache G: Continuity of care, residence, and family burden in Ohio. Milbank Quarterly 72:149-169, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lehman AF, Postrado LT, Roth D, et al: Continuity of care and client outcomes in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation program on chronic mental illness. Milbank Quarterly 72:105-122, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Wolkon GH: Characteristics of clients and continuity of care in the community. Community Mental Health Journal 6:215-221, 1970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bass RD, Windle C: Continuity of care: an approach to measurement. American Journal of Psychiatry 129:110-115, 1972Link, Google Scholar

9. Bass RD, Windle C: A preliminary attempt to measure continuity of care in a community mental health center. Community Mental Health Journal 9:53-62, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Barbato A, Terzian E, Saraceno B, et al: Patterns of aftercare for psychiatric patients discharged after short inpatient treatment. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 27:46-52, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Tessler RC, Willis G, Gubman GD: Defining and measuring continuity of care. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 10:27-38, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Pugh TP, MacMahon B: Measurement of discontinuity of psychiatric inpatient care. Public Health Reports 82:533-538, 1967Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Tessler RC: Continuity of care and client outcome. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 11:39-53, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Brekke JS, Test MA: A model for measuring the implementation of community support programs: results from three sites. Community Mental Health Journal 28:227-247, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bachrach LL: Continuity of care for chronic mental patients: a conceptual analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:1449- 1456, 1981Link, Google Scholar

16. Bachrach LL: Continuity of care and approaches to case management for long-term mentally ill patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:465-468, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

17. Johnson S, Prosser D, Bindman J, et al: Continuity of care for the severely mentally ill: concepts and measures. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32:137- 142, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

18. Evans-Pritchard EE: The Nuer. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 1940Google Scholar

19. Turner V: The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 1967Google Scholar

20. Rhodes LA: Emptying Beds: The Work of a Psychiatric Emergency Unit. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1991Google Scholar

21. Bourgois P: In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1995Google Scholar

22. Koegel P: Through a different lens: an anthropological perspective on the homeless mentally ill. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 16:1-22, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Geertz C: The Interpretation of Cultures. New York, Basic Books, 1973Google Scholar