Hallucinations, Delusions, and Thought Disorder Among Adult Psychiatric Inpatients With a History of Child Abuse

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The relationship between three positive symptoms of schizophrenia—hallucinations, delusions and thought disorder—and childhood physical and sexual abuse among psychiatric inpatients was investigated. METHODS: From the records of 100 consecutive admissions to an acute psychiatric inpatient unit in a New Zealand general hospital, the records of the 22 patients in which a history of either physical or sexual childhood abuse was mentioned were examined for data on the frequency and content of hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder. RESULTS: Seventeen of the 22 patients exhibited one or more of the three symptoms. Half of the symptoms for which content was recorded appeared to be related to the abuse. An analysis of the relationships between types of abuse and specific symptoms suggested that hallucinations may be more common than delusions or thought disorder among patients who have been sexually abused, particularly among those who have experienced incest, and that delusions may be more related to having been physically abused. CONCLUSIONS: The study findings confirmed previous findings of a high frequency of auditory hallucinations, particularly command hallucinations to kill oneself, and paranoid ideation among inpatients with a history of abuse. The hypothesis that the hallucinations of abuse survivors are "pseudohallucinations" was not supported.

In a recent review of 15 studies, 64 percent of female psychiatric inpatients reported childhood sexual or physical abuse; 50 percent reported sexual abuse, and 44 percent reported physical abuse (1). Male inpatients report similar rates of childhood physical abuse (2). Their reported rates of childhood sexual abuse range from 24 to 39 percent (3,4,5).

Particularly high rates of abuse are found in samples of patients with psychoses (6,7). Psychosis is, of all diagnostic categories, the most strongly correlated with child abuse (8,9,10). Of 100 child inpatients, 77 percent of those who had been sexually abused received a diagnosis of a psychosis, compared with 10 percent of those who had not been abused (11). Compared with other psychiatric patients, patients who had been abused as children have earlier first admissions, have longer and more frequent hospitalizations, spend more time in seclusion, are more likely to receive psychotropic medication, relapse more frequently, and are more likely to attempt suicide (1,12).

In one sample composed predominantly of female outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 92 percent had suffered childhood sexual or physical abuse (13). In a sample composed entirely of female inpatients with schizophrenia, 60 percent had suffered childhood sexual abuse (7). Compared with women without a history of abuse, women who are incest survivors scored higher on the schizophrenia scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (9). This finding is consistent with those of similar studies (14,15,16).

Physically or sexually abused patients with schizophrenia scored at the 75th percentile of norms for patients with this disorder on the Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale, compared with the 35th percentile for patients with schizophrenia who had not been abused (17). In a study of women patients in a psychiatric emergency room, in which logistic regression was used to control for the potential effects of demographic variables that also predict victimization or psychiatric outcome, childhood sexual abuse was related to nonmanic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia or psychosis not otherwise specified, and to depressive disorders; it was not related to manic disorders or anxiety disorders (18).

Abused patients are particularly likely to experience positive symptoms, such as hallucinations (3,19,20). Among 83 inpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, those who had been sexually or physically abused as children were more likely than the patients who had not been abused to have experienced paranoid ideation, thought insertion, visual hallucinations, and ideas of reading someone else's mind (p<.05); they had an even greater likelihood of having ideas of reference (p<.002) and hearing voices making comments (p<.001) (17). The researchers suggested that the results were compatible with at least two possible pathways to positive symptoms of schizophrenia—one that is primarily endogenous and accompanied by predominantly negative symptoms, and another that may be driven primarily by childhood social trauma and accompanied by fewer negative symptoms.

Consistent with findings in a study of child incest survivors (21), adult incest survivors are more likely to experience sexual delusions than are other inpatients (6). Significantly more paranoid ideology was found among female inpatients who suffered sexual or physical child abuse than among female inpatients without a history of abuse (8). However, another study found that inpatients who were abused as children were no more likely to experience auditory hallucinations, sexual delusions, or thought disorder than were inpatients who had not been abused (22). In that study, abused patients were more likely to experience hallucinations of voices inside their heads than were patients who had not been abused. Sexually abused patients were also more likely to experience visual hallucinations. The authors concluded that a history of childhood abuse may contribute to the symptoms and course of illness of some patients with chronic psychoses.

In a study of 40 female patients, Ellenson (19) identified a syndrome shared by and exclusive to incest victims. The symptoms fell into two categories. The first consisted of thought content disturbances, predominantly nightmares, obsessions, dissociation, and phobias. The second category was perceptual disturbances, which consisted primarily of illusions and hallucinations. The auditory hallucinations commonly took the form of sounds of an intruder, such as "footsteps, breathing, bumps, scrapes, doorknobs turning, doors opening and closing, and windows being tampered with," and of voices that were persecutory or directive or were inner-helper voices (23). The persecutory voices were experienced inside the head and either condemned the patient in sexual terms or threatened harm. The directive voices goaded the patient to harm herself, to attempt suicide, or to commit acts of violence.

In a study of ten patients, Heins and associates (20) confirmed Ellenson's findings about hallucinations. However they described the symptoms as "pseudohallucinations." Such reinterpretation of psychotic symptoms and diagnoses as something less serious, once the patient is found to have a history of abuse, is common among researchers and clinicians and has been identified as one of several processes that can mask the possibility that child abuse is etiologically related to schizophrenia (1).

The study reported here sought to answer four questions. First, what proportion of patients with a history of sexual or physical abuse in a sample of consecutive admissions to an acute psychiatric inpatient unit exhibit hallucinations, delusions, or thought disorder? Second, are the three symptoms related in different ways to different forms of child abuse? Third, are the hallucinations experienced by abuse survivors "pseudohallucinations"? Fourth and finally, to what extent does symptom content appear to be related to abuse?

Methods

As part of a study examining the value of taking a history of abuse when patients are admitted to acute psychiatric inpatient care (12,24), the medical records of 100 consecutive admissions to an acute psychiatric inpatient unit of a New Zealand general hospital were read. The files of 22 patients that revealed childhood sexual or physical abuse, including seven cases involving both sexual and physical abuse, were reexamined, and the presence and content of hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder were noted. To be included in the analysis, symptoms needed to be clearly identified in the record as hallucinations, delusions, or thought disorder.

Statistical analyses of the relationship between a specific type of abuse and a specific symptom—both nominal categories—used the phi coefficient. In the analysis using ratio scale data—the total number of symptoms—a two-tailed t test was used.

Of the 22 abused inpatients, 12 were women. The mean±SD age of the 22 patients was 35.5±8.6 years. Sixteen were of European descent, three were Maori, and three were Pacific Islanders. The most frequent diagnoses were major depressive disorder for eight patients, schizophrenia for four patients, and bipolar affective disorder for four patients. Six patients had dual diagnoses, four of which involved substance abuse.

Results

Prevalence of symptoms of schizophrenia

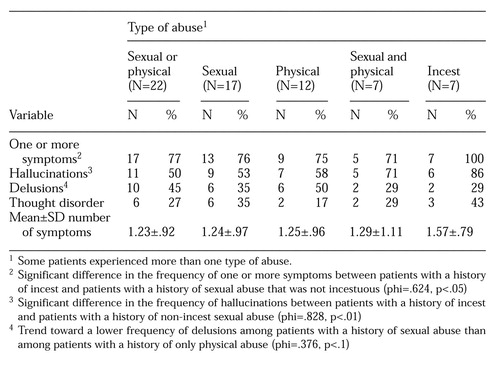

Table 1 shows that 17 of the 22 abused inpatients (77 percent) exhibited hallucinations, delusions, or thought disorder. Patients who were in the three major abuse categories—sexual, physical, and both sexual and physical—and patients of both genders were similarly likely to exhibit one or more of these symptoms. All seven incest survivors exhibited one or more symptoms, compared with two of the four patients who had experienced sexual abuse by an extrafamilial perpetrator (phi=.624, p<.05). (In the remaining six sexual abuse cases, the perpetrator was unidentified.)

Patients who were incest survivors had a higher mean number of symptoms (mean±SD=1.57±.79) than patients who had been sexually abused by extrafamilial perpetrators (mean± SD=.75±.96). Among male patients, the difference in the mean number of symptoms between incest survivors and those who had been sexually abused by extrafamilial perpetrators approached significance (mean±SD= 1.33±.58, compared with .33±.58; t=2.12, two-tailed, df=4, p=.10).

Relationship of symptoms to type of abuse

Hallucinations.

Eleven of the 22 patients experienced auditory hallucinations, and two of the 11 experienced visual hallucinations. Hallucinations were equally frequent among patients who had been sexually abused (53 percent) and among those who had been physically abused (58 percent). Of those who were both physically and sexually abused, 71 percent exhibited hallucinations, compared with 40 percent of those suffering only one type of abuse (phi=.293, p=.17).

All three of the women who had been both physically and sexually abused exhibited hallucinations, compared with three of the nine women who had experienced only one type of abuse (phi=.577, p<.05). Six of the seven incest victims experienced hallucinations, compared with none of the four patients who were sexually abused by a nonfamilial perpetrator (phi=.828, p<.01).

Delusions.

Ten of the 22 patients (45 percent) experienced delusions. Seven of the 12 women, but only three of the ten men, exhibited delusions (phi=.283, p=.18). Delusions were reported for six of the 17 sexually abused patients (35 percent) and four of the five patients who experienced only physical abuse (80 percent) (phi=.376, p=.08).

Thought disorder.

Six of the 22 patients (27 percent) had thought disorder. The patients with thought disorder included six of the 17 sexually abused patients (35 percent) but none of the patients who had experienced only physical abuse (phi=.332, p=.12). None of the seven physically abused women had thought disorder, compared with three of the five women who had not been physically abused (phi=.683, p<.05). Three of the seven incest survivors had thought disorder, compared with one of the four patients whose sexual abuse was not incestuous, a clearly nonsignificant difference. Two of the three male incest victims but none of the three male patients whose sexual abuse was not incestuous had thought disorder, which approached significance (phi=.707, p=.08).

Content of symptoms

The records of the 22 patients who had been abused included 27 instances in which hallucinations, delusions, or thought disorder were mentioned. Hallucinations were mentioned 11 times, delusions ten times, and thought disorder six times. However, the content of the symptoms was described in only 13 of the 27 instances—seven descriptions for hallucinations, five for delusions, and one for thought disorder. The finding that the records of only one of the six patients with thought disorder included any description of content presumably reflects the fact that thought disorder affects the process of thought more than the content. In the other 14 instances, symptoms were described simply as "auditory hallucinations" or "paranoid delusions" or in other general terms.

The symptom content appeared to be related to abuse in three of the seven instances in which some content of hallucinations was recorded, in three of the five instances in which content of delusions was recorded, and in the one instance in which the content of thought disorder was recorded. Overall, in seven of the 13 cases (54 percent), symptom content was not related to abuse.

Hallucinations.

In three of the seven instances in which content was recorded, the content appeared to be related to the abuse experienced by the patient. One example involved a woman whose file recorded sexual abuse by her father from age five. Besides hearing command hallucinations to kill herself, she heard "male voices outside her head and screaming children's voices inside her head." The second example also involved command hallucinations to commit suicide; the patient identified the voice as the alleged perpetrator of the abuse, the patient's mother, who had physically and emotionally abused the patient as a child. The third example involved a patient who heard the voice of his father saying, "You have died" or "You were shot." The patient's record identified the father as having physically abused the patient as a child. This patient, who was also sexually abused, also heard voices saying, "Go up him" and "Go down him."

In a fourth example, involving a patient who had been sexually abused by his grandfather, the record reported a visual hallucination of "seeing an old man." This hallucination was categorized as possibly abuse related. The three instances of hallucinations that were judged to be unrelated to abuse involved unspecified voices commanding suicide and the voices of brothers' spirits and the voice of a grandson; in the last two instances, content was not recorded.

Delusions.

Five of the six instances in which delusions were categorized in the files as either paranoid-persecutory or grandiose (or for which the content permitted such categorization) involved paranoid or persecutory ideation. Two of these five instances also involved grandiose delusions. The sixth instance involved grandiose delusions without paranoid delusions.

Of the five instances of delusions for which specific content was recorded, three appeared to be related to the abuse that had been experienced by the patient. One instance involved a woman whose "persecutory delusions" included the belief that "men were out to get her and harm her and sexually harass her." The record described her as having been sexually molested by an older man when she was a child. The second instance involved a man who had been sexually abused from age four. He believed his body was assymetrical and that women who wanted to have sex with him did so because of the "thrill of being with a freak." The third instance involved a man who had been physically abused by his father. He experienced "paranoid delusions of persecution with fears of being killed" and ideas of reference that violence depicted on television was related to him. The two instances judged to be unrelated to abuse were delusions that one's role was to save the world and that a sparrow was reading one's mind.

Thought disorder.

The only instance of thought disorder for which any content was recorded involved an incest victim whose "disorganized thoughts" included "distorted ideas of sexuality."

Discussion and conclusions

Methodological limitations

The prevalence of abuse is significantly underestimated when it is based on case files rather than interviews with patients themselves (1,4,25). The statistical analyses in this study involved only the minority of abused patients whose records indicated they had been abused.

The paucity of information on symptom content and the identity of the perpetrator of abuse reduced the number of records available for analysis. Because the analyses used a large number of statistical tests, caution should be exercised in interpreting claims of statistical significance due to the high risk of type I errors.

Furthermore, this exploratory study did not compare the frequency or content of the symptoms of abused patients with that of their counterparts who did not have a history of abuse. Replication of the research reported here should include such comparisons, as well as a larger sample size. Data on 200 outpatients in the Auckland region has recently been gathered in a way that permits comparisons between abused and nonabused patients.

Overall symptom frequency

Ross and associates (17) reported that among the symptoms more likely to occur among patients with schizophrenia who had been abused than among those who had not been abused, the three most frequent were ideas of reference (77 percent), voices commenting (69 percent), and paranoid ideation (54 percent). In the study reported here, the respective proportions were 40 percent for ideas of reference, 50 percent for all auditory hallucinations, and 62 percent for paranoid ideation. Goff and associates (22) also found that auditory hallucinations were common among abused inpatients, occurring among 74 percent of the abused inpatients in their sample.

Sexual abuse

Sexually abused inpatients were equally likely to experience delusions as thought disorder (35 percent). However, the possibilities that sexual abuse may be particularly related to hallucinations (53 percent) may be worthy of further investigation. A previous study found hallucinations to be more common among sexually abused patients than among those who were not sexually abused, but found no difference between the two groups in likelihood of delusions (3).

Previous studies have demonstrated relationships between sexual abuse and sexual delusions (6,11). In the study reported here, among patients for whom any delusional content was recorded, sexual content was recorded for none of the physically abused patients but 50 percent of the sexually abused patients. Another sexually abused patient experienced thought disorder involving "distorted ideas of sexuality."

The difference in the frequency of thought disorder among sexually abused patients and among physically abused patients (35 percent and 17 percent, respectively) was not statistically significant. However, because thought disorder was not recorded for any of the patients who were subjected to only physical abuse, the possibility of a greater frequency of thought disorder among sexually abused patients than among physically abused patients may warrant further study with a larger sample.

Physical abuse

Physically abused patients did not differ from sexually abused patients in the frequency of hallucinations or of the three types of symptoms combined. The nonsignificant trends toward a higher frequency of delusions and a lower frequency of thought disorder among physically abused patients may warrant further investigation.

Severity of abuse

Incest, a particularly damaging trauma, was related to the likelihood of hallucinations (p<.01) but not to the likelihood of the other two schizophrenic symptoms. Patients who had been both physically and sexually abused were also more likely to experience hallucinations than those who experienced only one type of abuse, although the difference was not statistically significant (p=.17). Further research examining the specificity of sensory and perceptual distortions versus cognitive distortions may benefit from considering the overlap between the symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, including dissociation, and the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, including hallucinations and paranoid delusions (1,17,26,27). Such research could also incorporate concepts based on the findings of Perry and associates (28,29) about the neurodevelopmental mechanisms connecting childhood trauma to dissociative and other disorders later in life.

Ellenson's postincest syndrome

The study reported here supported Ellenson's finding (19,23) about the universality of hallucinations among female psychiatric patients who have suffered incest. Hallucinations were reported for all four female incest survivors in the study. Two of the three male incest survivors also exhibited hallucinations. The proportion of incest survivors who experienced hallucinations (six of seven patients) was significantly different from the proportion of patients with a history of sexual abuse that was not incestuous (one of four patients) (p<.01). The study also provides some support for Ellenson's finding of a high frequency of voices telling incest survivors to harm or kill themselves. The two female incest survivors for whom some content was available heard voices commanding suicide.

Pseudohallucinations

The hypothesis of Heins and associates (20) that hallucinations experienced by child abuse survivors are not genuinely schizophrenic hallucinations was not supported by this study. According to Heins and associates (20), pseudohallucinations are "experienced as emanating from the mind" rather than "perceived as out there in the world"; they describe pseudohallucinations as "elementary" in that they are "vague, fleeting, and ill-defined." DSM-IV (30) makes no reference to pseudohallucinations but states that "isolated experiences of hearing one's name called or experiences that lack the quality of an external percept," such as humming in one's head, are not considered hallucinations characteristic of schizophrenia.

In this study, none of the 11 instances of hallucinations reported in the patients' charts were described in the terms often used to reclassify hallucinations as something less severe once abuse has been identified—such as pseudohallucinations, psychotic-like hallucinations, dissociative hallucinations, quasipsychotic posttraumatic symptoms, or hysterical psychosis (1). None of the notes describing the content of hallucinations mentions characteristics that would match Heins and associates' description (20) of pseudohallucinations or the DSM-IV criteria for categorizing the hallucinations as nonschizophrenic.

Heins and associates and Ellenson (19,23) suggested that true hallucinations are found only among incest survivors who are substance abusers. In this study, only three of the 11 sexual abuse survivors with hallucinations and none of the four female incest survivors with hallucinations were diagnosed as substance abusers.

Theoretical implications

The study findings about the relatedness of symptom content to abuse suggest that the distressed confusion of many people who experience hallucinations, delusions, or disordered thinking might be better understood if a psychosocial perspective were given as much emphasis as the dominant biological framework. One product of the latter paradigm is the paucity of information gathered about the content of psychotic symptoms. In this study, even the records of patients for whom some symptom content was noted included little detail and no formulation of the relationship between content and life events. The prevailing paradigm judges the content to be irrelevant, so even the most obvious links between symptoms and pyschosocial history are missed.

Future research should consider the function of symptoms in relation to their psychosocial context (31). Goff and associates (32) suggested that the delusions they found to be related to abuse function to resolve intrapsychic conflict through externalization, allow patients some control through their assumption of the sick role, and allow the expression of otherwise unacceptable behaviors. Ellenson (23) has offered examples of hallucinations that serve as defensive coping mechanisms, adding that the hallucinations of incest survivors are usually "intrusive recollections that take the form of sensory phenomena." The possibility that for some people, for some periods, these memories can only be experienced symbolically, was considered by Freud (33). After the treatment of an incest survivor was terminated when she developed "severe hallucinations which had all the signs of dementia praecox," Freud wrote that "these hallucinations were nothing else than parts of the content of repressed childhood experiences."

Seventeen of the 22 abused inpatients in this study (77 percent) experienced one or more of the three symptoms of schizophrenia we considered, and nine of the abused inpatients (41 percent) experienced two or more symptoms. However only four of those patients (18 percent) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, compared with 30 of the 78 patients (38 percent) for whom child abuse was not identified. Thus child abuse appears to be related to symptoms of schizophrenia but not to a diagnosis of schizophrenia. These findings are not inconsistent with the hypothesis developed elsewhere that when a case of child abuse is identified, clinicians may avoid a diagnosis of psychosis (1). This tendency may be motivated by the desire to formulate a diagnosis more likely to result in abuse-focused psychological intervention, such as depression or PTSD, and by the belief that abuse is not related to the types of mental illness believed to be predominantly biogenetic in origin, such as schizophrenia.

An alternative, or additional, explanation is that the three symptoms studied occur in other diagnostic categories, including affective disorders. Indeed, as noted earlier, child abuse has been found to be related not only to schizophrenia but to several measures of overall severity of disturbance within inpatient populations and also to psychosis in general.

Clinical implications

Ellenson (19,23) and Heins and associates (20) have suggested that one reason for defining a postabuse syndrome is to provide indicators of the need for clinicians to inquire about abuse. The schizophrenic symptom most consistently found among sexual abuse survivors is auditory hallucination. Command hallucinations to commit suicide and persecutory or paranoid ideation in general may also be useful indicators that inquiry is warranted. Many other researchers and clinicians, however, recommend that all patients be routinely asked about abuse (1,2,3,8,10,34).

The clinical importance of gathering abuse histories, in both inpatient and community settings (35), includes possible reduction in stigmatization; other research has shown that stigmatization is decreased when disorders are perceived to be related to psychosocial trauma rather than thought of as biologically based "mental illnesses" (36). Knowledge of a history of abuse can also lead to facilitation of abuse-focused psychotherapy (1,37,38). Once clinicians overcome the tendency to ignore the association between abuse and functional psychosis (1), they may then consider new combinations of interventions for psychiatric inpatients with a history of abuse. A promising therapeutic path consists of an integration of psychodynamically oriented trauma-focused therapy (39) with cognitive approaches proven to be successful with symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions (40,41).

Dr. Read is senior lecturer in the psychology department at the University of Auckland, Private Bag 92109, Auckland 1, New Zealand (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Argyle is honorary senior lecturer in the department of psychiatry and behavioral science at the University of Auckland.

|

Table 1. Prevalence of three primary symptoms of schizophrenia among 22 inpatients with a history of sexual or physical abuse

1. Read J: Child abuse and psychosis: a literature review and implications for professional practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 28:448-456, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Jacobson A, Richardson B: Assault experiences of 100 psychiatric inpatients: evidence of the need for routine inquiry. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:508-513, 1987Link, Google Scholar

3. Sansonnet-Hayden H, Haley G, Marriage K, et al: Sexual abuse and psychopathology in hospitalized adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 26:753-757, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wurr JC, Partridge IM: The prevalence of a history of childhood sexual abuse in an acute adult inpatient population. Child Abuse and Neglect 20:867-872, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Jacobson A, Herald C: The relevance of childhood sexual abuse to adult psychiatric inpatient care. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:154-158, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Beck JC, van der Kolk BA: Reports of childhood incest and current behavior of chronically hospitalized psychotic women. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1474-1476, 1987Link, Google Scholar

7. Friedman S, Harrison G: Sexual histories, attitudes, and behavior of schizophrenic and normal women. Archives of Sexual Behavior 13:555-567, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bryer JB, Nelson BA, Miller JB, et al: Childhood sexual and physical abuse as factors in psychiatric illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1426-1430, 1987Link, Google Scholar

9. Lundberg-Love PK, Marmion S, Ford K, et al: The long-term consequences of childhood incestuous victimization upon adult women's psychological symptomatology. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 1:81-102, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Swett C Jr, Surrey J, Cohen C: Sexual and physical abuse histories and psychiatric symptoms among male psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:632-636, 1990Link, Google Scholar

11. Livingston R: Sexually and physically abused children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 26:413-415, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Read J: Child abuse and severity of disturbance among adult psychiatric inpatients. Child Abuse and Neglect 22:359-368, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Goodman LA, Dutton MA, Harris M: Physical and sexual assault prevalence among episodically homeless women with serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:468-478, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Briere J: Therapy for Adults Molested as Children: Beyond Survival. New York, Springer, 1989Google Scholar

15. Scott RL, Stone DA: MMPI profile constellations in incest families. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 54:364-368, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Carlin AS, Ward NG: Subtypes of psychiatric inpatient women who have been sexually abused. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:392-397, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ross CA, Anderson G, Clark P: Childhood abuse and the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:489-491, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Briere J, Woo R, McRae B, et al: Lifetime victimization history, demographics, and clinical status in female psychiatric emergency room patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:95-101, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Ellenson GS: Detecting a history of incest: a predictive syndrome. Social Casework 66:525-532, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Heins T, Gray A, Tennant M: Persisting hallucinations following childhood sexual abuse. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 24:561-565, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Fish-Murray C, Koby E, van der Kolk BA: Cognitive impairment in abused children, in Psychological Trauma. Edited by van der Kolk BA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1987Google Scholar

22. Goff DC, Brotman AW, Kindlon D, et al: Self-reports of childhood abuse in chronically psychotic patients. Psychiatry Research 37:73-80, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Ellenson GS: Disturbances of perception in adult female incest survivors. Social Casework 67:149-159, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Read J, Fraser A: Abuse histories of psychiatric inpatients: to ask or not to ask ? Psychiatric Services 49:355-359, 1998Google Scholar

25. Briere J, Zaidi LY: Sexual abuse histories and sequelae in female psychiatric emergency room patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:1602-1606, 1989Link, Google Scholar

26. Ellason JW, Ross CA: Positive and negative symptoms in dissociative identity disorder and schizophrenia: a comparative analysis. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:236-241, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Butler RW, Mueser KT, Sprock J, et al: Positive symptoms of psychosis in postraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry 39:839-844, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Perry BD: Neurobiolgical sequelae of childhood trauma: PTSD in children, in Catecholamine Function in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Emerging Concepts. Edited by Murburg M. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

29. Perry BD, Pate JE: Neurodevelopment and the psychobiological roots of post-traumatic stress disorders, in The Neuropsychology of Mental Illness: A Practical Guide. Edited by Koziol LF, Stout CE. Springfield, Ill, Thomas, 1994Google Scholar

30. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

31. Ellenson GS: Horror, rage, and defenses in the symptoms of female sexual abuse survivors. Social Casework 70:589-596, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Goff DC, Brotman AW, Kindlon D, et al: The delusion of possession in chronically psychotic patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 179:567-571, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Freud S: A case of chronic paranoia, in Further Remarks on the Neuro-Psychoses of Defence, in Collected Papers of Sigmund Freud, vol 1. Edited by Jones E. London, Hogarth, 1950Google Scholar

34. Herman JL: Histories of violence in an outpatient population: an exploratory study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 56:137-141, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Allen R, Read J: Integrated mental health care: practitioners' perspectives. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 31:534-541, 1997Google Scholar

36. Read J, Law A: The relationship of causal beliefs and contact with users of mental health services to attitudes to the "mentally ill." International Journal of Social Psychiatry 45:216-229, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Read J: The role of psychologists in the assessment of psychosis, in Practice Issues for Clinical and Applied Psychologists in New Zealand. Edited by Love H, Whittaker W. Wellington, New Zealand Psychological Society, 1997Google Scholar

38. Read J, Fraser A: Staff response to abuse histories of psychiatric inpatients. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 32:157-164, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Herman JL: Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. New York, Basic Books, 1992Google Scholar

40. Haddock G, Slade P: Cognitive Behavioural Interventions With Psychotic Disorders. London, Routledge, 1995Google Scholar

41. Kingdon DG, Turkington D: Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy of Schizophrenia. Hove, United Kingdom, Erlbaum, 1994Google Scholar