Clinicians' and Clients' Perspectives on the Impact of Assertive Community Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Clients in an assertive community treatment program and their clinicians were asked to rate clients' current difficulties in 13 quality-of-life areas to determine whether improvement in any area predicted reductions in hospitalization and incarceration. METHODS: A peer counselor interviewed 45 clients about psychiatric symptoms, substance use and abuse, medical issues, medication compliance, primary supports, social supports, vocational and occupational issues, housing, daily living skills, economic issues and entitlements, legal involvement, behavioral issues, and treatment involvement. The clients' clinicians rated the clients in these same areas. Ratings of clients' difficulties in these areas at program entry were based on combined ratings made at intake and after a review of clients' charts. Data on hospitalization and incarceration were obtained from medical and police records. Logistic regression analyses were used to seek predictors of declines in admissions to hospitals and jails (referred to as institutional admissions). RESULTS: Institutional admissions decreased after program entry; decreases were larger among clients admitted in recent years. Clients improved significantly in all 13 quality-of-life areas based on comparisons of both clinicians' and clients' ratings and baseline ratings; however, clients rated themselves as having less difficulty than their clinicians thought they had in the areas of substance abuse, medication compliance, primary supports, social supports, daily living skills, and treatment involvement. Based on clinicians' ratings, improvement in substance abuse issues predicted declines in institutionalized admissions. Based on clients' ratings, improvement in social support and economic issues predicted declines. CONCLUSIONS: These findings emphasize the importance of clients' perspectives in treatment planning and suggest that clinicians may overlook the smaller incremental steps toward improvement that are valued by clients.

Most people with severe mental illnesses can live productive lives in the community if they receive treatment and assistance in meeting basic needs, such as housing, vocational pursuits, acquisition of entitlements, education, social services, transportation, and medical care. However, many cannot negotiate traditional service systems and require persistent and continued assertive outreach efforts before a trusting relationship can be established and assistance provided.

The assertive community treatment (ACT) model is designed to render multidisciplinary specialized outreach services, provide links to comprehensive resources and psychosocial services, and address the complex factors that cause prolonged homelessness among people with severe mental illnesses (1). In most studies client improvement is measured only by service utilization rates, such as hospitalization. Seldom do researchers consider clients' perspectives and the complexities of a variety of tragic circumstances that individuals with severe psychiatric disabilities endure in daily living.

This study elicited clients' and clinicians' perspectives on clients' improvements in several areas after they entered an assertive community treatment program. Data were examined to determine whether improvements or continued difficulties in any of these areas, as seen from the perspective of the clients or the clinicians, predicted reductions or increases in admissions to hospitals and jails.

Literature review

Numerous studies have demonstrated that ACT programs can reduce psychiatric admissions and rehospitalization as well as lengths of stay (2,3,4,5,6,7,8). ACT programs have been shown to constitute a cost-effective alternative to psychiatric hospitalization (9,10,11,12,13,14). In comparison studies, ACT teams typically emerge as superior interventions in reducing hospitalization. For example, in a study comparing ACT and high-quality case management, clients with serious mental illness fared better with ACT and were hospitalized half as often as clients provided standard services (4). In a comparison of a hospital-based program and an ACT team, clients in the latter were more likely to be maintained in community settings and reported better quality of life than clients in the former (15).

Bond and colleagues (16) found that ACT clients averaged significantly fewer hospitalizations than clients receiving treatment at a drop-in center. In another study at ten Department of Veterans Affairs sites in the Northeast, nearly 1,000 frequent users of inpatient hospitalization were assigned to either standard care or ACT programs and followed for two years. ACT clients used a third fewer hospital days than clients in the control group, resulting in a 20 percent reduction in treatment costs (9).

Some researchers have explored specific precipitants of hospitalization; however, the range of determinants varies, making comparisons difficult. Predictors of psychiatric hospitalization include factors related to symptoms as well as social, financial, and legal factors (17); medication noncompliance (18); low levels of functioning and inadequate social supports (19); dissatisfaction with family relations and recent arrest (20); and socioeconomic status (21). However, the majority of these studies base predictors of recidivism on clinicians' reports and neglect the client's point of view.

Only a handful of studies have included clients' perspectives in assessment of needs and treatment outcomes, and even fewer have considered their perspectives as potential predictors of hospitalization. For example, positive feedback from clients about interventions specific to assertive community treatment, such as staff availability and home visits, was associated with a reduction in hospitalization (22). In addition, clients' reports about a positive therapeutic alliance were linked to improved community living skills and better outcome (23).

Discrepancies between clinicians' and clients' perceptions of needs have been noted. In one study clinicians were more likely to identify clients' needs as mental health related, such as the need for substance abuse and mental health services, while clients identified dental and medical services as necessities (24). It is unclear whether these client-clinician contrasts influence treatment involvement, process, and outcome in ACT programs.

Research studies have provided an impressive array of findings about the cost-effectiveness of ACT programs. The efficacy of ACT programs with regard to other clinical outcomes has also been demonstrated. These programs have been successful in improving community tenure, treatment involvement, housing stability, and support systems, although they are not without limitations. In one study, homeless individuals with severe mental illness who were enrolled in an ACT program adhered to treatment recommendations in most domains except for daily structure, suggesting the importance of low-demand housing and drop-in centers (25). In South Carolina, treatment involvement and housing stability improved for all ACT clients except the most severe substance users, who did not gain social benefits and had low rates of abstinence (26).

Although improvements and reductions in hospitalization have been notable, evidence suggests that since deinstitutionalization, persons with chronic psychiatric disabilities have experienced increased homelessness or have been shifted to surrogate mental hospitals (27,28,29). Studies examining the effects of deinstitutionalization over the past 20 years have noted the criminalization of the mentally ill. Many requiring institutionalized care find themselves in correctional facilities, because communities are unprepared to provide services (27,28,2930,31,32). Arrest and incarceration rates are high among homeless persons with mental illness; many are jailed for relatively trivial and nonviolent offenses, and law enforcement officials find it easier to incarcerate them than to obtain hospitalization or treatment (33,34,35,36). Programs designed to divert mentally ill inmates back to mental health facilities are promising, yet only a small number of U.S. jails have diversion programs for mentally ill detainees (37).

Belcher (38) found that for many psychiatrically disabled and homeless individuals, a combination of severe mental illness, a tendency to decompensate in unstructured settings, and treatment noncompliance contribute to involvement in the criminal justice system. Difficulties in monitoring this population are notable. In one study inmates with serious mental illness who were discharged from the legal system were assigned to treatment by a community mental health center, an intensive forensic case management program, or an ACT team (39). No differences between the three groups in jail recidivism were found. However, another study found that although the majority of ACT clients continued to have contacts with the law enforcement system, most encounters and arrests were for minor infractions (40).

Clients who are appropriate for ACT programs have complex and multifaceted problems, which raise questions about the specific factors that may contribute to rehospitalization. For example, do reductions in rehospitalization among ACT clients reflect simply a shift in institutional settings, such as from a hospital to a jail? Another question is whether rehospitalization and rearrest can be prevented altogether.

The study reported here explored three areas. First, are rates of clients' use of institutional settings—both hospitals and jails—reduced after treatment by an ACT team? Second, do clinicians' and clients' perspectives about clients' improvement in selected treatment areas differ? Third, what factors predict declines in admission to an institution, and do clinicians' and clients' perspectives on these predictors differ?

Methods

The ACT team

The ACT team at the Connecticut Mental Health Center in New Haven was established in 1992 and provides treatment to a multicultural client population. Clients have long histories of mental illness and substance use disorders. They are often homeless and have severely limited resources. The team integrates professionals from several disciplines, such as nurses, psychiatrists, social workers, and a psychologist, together with paraprofessional mental health workers who constitute approximately half the team. One of the team members is a peer counselor with a history of serious mental illness who serves as a role model to clients and provides a consumer's perspectives to the staff.

Although each client is assigned a primary clinician to provide case management, the team approach is embraced extensively in treatment planning and clinical care. Staff work collaboratively, providing in vivo intensive community support; crisis intervention; individual, family, and group therapy; medication delivery; money management, housing, and vocational assistance; and advocacy with other service systems. The team's philosophy combines both the "growth-oriented" and "survival-oriented" descriptors on the continuum developed by Bond and associates (16). The team strives to improve quality of life through skill building while also attempting to reduce hospitalization through resource management (41).

Respondents

Respondents to the survey conducted in this study were clients of the team in the fall of 1997. At that time 61 clients were served by the team, and 45 agreed to participate (74 percent). Each client's primary clinician also responded to the survey. Clients from every primary clinician were represented in the sample, ranging from two to five clients of each clinician. Only four of the surveyed clients (9 percent) had a new clinician in the previous 12 months, while the majority (33 clients, or 73 percent) were followed by the same clinician for an average of 29 months.

It was not possible to survey all the clients who had received services from the team since the beginning of the program because some had been discharged, some dropped out, and some had died. However, demographic, hospitalization, and incarceration data were obtained from program records.

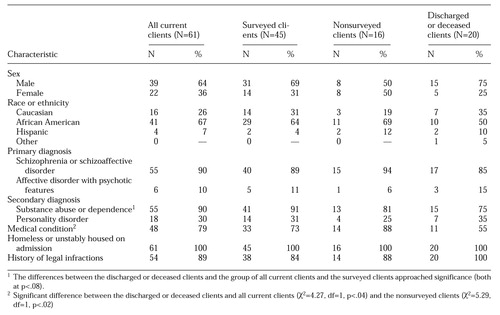

Information about all current clients, clients who participated in the survey, clients who refused to participate, and clients discharged or deceased is provided in Table 1. Clients who dropped out are included in the discharged group. The mean ages of the four groups did not differ significantly. The mean±SD age of all 61 current clients was 41.8±9 years. It was 41.6±9.4 for the 45 surveyed clients, 42.4±9.3 for the 16 clients who refused to participate, and 41.0±10.7 for the 20 discharged or deceased clients.

The mean±SD number of months in the program for all current clients was 29.1±18.3, compared with 30.5±18.2 for the surveyed clients, 27.6±19.1 for the clients who refused to participate in the study, and 20.4±14 for the discharged or deceased clients. The discharged or deceased group had spent significantly less time in the program than the group of all current clients (t=-1.95, df=79, p<.05) and the surveyed clients (t=-2.22, df=63, p<.03).

As Table 1 shows, no significant differences were found between the surveyed and nonsurveyed clients. To determine whether demographic characteristics differed as a function of time in the program, current clients were divided into two groups, those who had been in the program for less than the mean of 29 months and those who had been in the program longer. No significant demographic differences were found between the groups; in addition, no differences were found when clients were grouped by the number of years in the program.

As Table 1 shows, compared with the group of all current clients and the nonsurveyed group, a smaller proportion of the discharged or deceased group had a medical condition. In addition, a smaller proportion of the discharged or deceased group had a substance use disorder compared with all current clients and the surveyed group, but these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Archival data

Data on psychiatric hospitalizations and incarcerations were retrospectively collected for all 81 clients who received services from the team since its inception in 1992 through December 31, 1997 (N=81). Data for two years before each client's entry into the ACT program were also collected. Information was gathered from past medical and police records, from databases of three local inpatient facilities, and from a statewide database, including a local area network that records state facility admissions. Although the data collection involved an extensive search, it should be noted that information about private and out-of-state admissions may have been incomplete for the period before program entry. Thus calculations for this period are likely to be underestimates. However, because most clients remained in the area and did not frequent private institutions, missing data are likely minimal.

Survey

Clients and their respective clinicians were surveyed separately with the same instrument to gather information about their perspectives on client progress. Clients were interviewed; clinicians completed the survey themselves. The survey interview was conducted during the fall of 1997 by the peer counselor on the ACT team, who was trained to administer the instrument and help clarify areas of potential confusion.

The interview focused on 13 quality-of-life areas that were selected based on past and current treatment plans and difficulties reported by clients and clinicians. The areas were psychiatric symptoms, substance use and abuse, medical issues, medication compliance, primary supports, social supports, vocational and occupational issues, housing, daily living skills, economic issues and entitlements, legal involvement, behavioral issues, and treatment involvement.

The survey included brief examples about difficulties in each of the 13 areas to avoid misinterpretation and provide consistency. Two questions were asked about each of the areas. The first was whether the client was currently experiencing difficulties in that area. Clients and clinicians responded on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating no difficulties and 5 indicating severe difficulties. The second question was a measure of change in each area. Clients and clinicians simply responded whether they believed improvement or decline had occurred in the area since program entry.

The level of clients' difficulties at program entry (baseline) in each of the areas was also rated. The team director, who had conducted face-to-face interviews with each client at intake, retrospectively rated clients' difficulties in all 13 areas. The director's ratings were averaged with ratings provided by the first author, who reviewed individuals' charts. Interrater reliability for the baseline estimates across all 13 areas was high, matching 98 percent of the time (kappa=.97) for both the entire sample and the surveyed subsample.

Because the reliability tests indicated the accuracy of the baseline ratings, they were used to calculate progress scores according to both clients' and clinicians' perspectives. Progress scores were computed by subtracting the baseline rating in each area from the current rating. Two progress scores in each area were computed, one based on the client's current rating and one based on the clinician's.

Interrater reliability between clients and clinicians was low at best. Ratings for current status in all 13 areas matched 64 percent of the time (kappa=.59), and change indicators matched 61 percent of the time (kappa=.20). The accuracy of the ratings was explored further by comparing clients' and clinicians' responses to the second, yes-or-no question about change in the progress scores; comparisons for clinicians and for clients were made separately. Clients' ratings of their improvement or decline in each area matched the progress scores 61 percent of the time, 36 percent for improvement and 25 percent for declines. Clinicians' ratings matched progress scores 63 percent of the time, 44 percent for improvements and 19 percent for declines.

When the change indicators did not match the progress scores, the discrepancies tended to underestimate clients' progress—that is, the change indicator reflected a decline, whereas the progress score indicated improvement. This type of discrepancy occurred for 36 percent of the clients' ratings and for 35 percent of the clinicians' ratings. Rarely did clients or clinicians overestimate progress—that is, in only a few cases did a change indicator reflect improvement and a progress score indicate decline. This type of discrepancy occurred for 3 percent of the clients' ratings and 3 percent of the clinicians' ratings.

Qualitative data

Qualitative data were collected to supplement quantitative findings. Both clinicians and clients were briefly interviewed in the event of a hospitalization or incarceration. All such interviews were conducted either retrospectively for incidents occurring within the first six months of 1997 or within one or two days after the event during the second half of the year. The first author, who was the team psychologist at that time, conducted all interviews.

Interviews with the clients were held at the hospital or jail in the later months. Information was obtained from individual clinicians as well as from the team during daily clinical rounds. Clinical rounds involved feedback from all team members about possible precipitants to hospitalization or incarceration based on their interactions with the client and on secondary information provided by a client's family members or friends. Possible reasons for hospitalization or incarceration were recorded, as was the source of the information. The reasons were tallied for comparison. In most cases, input from clients' family members and friends coincided with clinicians' speculations; however, in cases of disagreement, only clinicians' reported reasons were used for client-clinician comparisons.

Analysis

The mean number of psychiatric hospitalizations and incarcerations for the two years before ACT program entry was calculated. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine whether significant changes in yearly admission rates occurred. If significant changes were found, post hoc paired comparisons were calculated to identify significant year-to-year changes. Univariate paired comparisons were conducted for groups with few individuals. To control for the number of years in the ACT program, clients were grouped into six categories: less than one year (mean±SD=5.72±3.56 months), one to two years, two to three years, three to four years, four to five years, and five years or longer.

Analyses of hospital admission and incarceration rates included all 81 current and discharged clients. Analyses of survey data included 45 clinician-client pairs. Paired t tests examined mean differences across all 13 quality-of-life areas. Three comparisons were made: baseline ratings were compared with clinicians' current ratings and with clients' current ratings, and clinicians' and clients' ratings were compared. For the paired t tests, familywise type I error rate was controlled by setting the significance level at p≤.01.

Stepwise logistic regressions were conducted to determine whether improvement in any of the 13 areas was associated with a decline in hospital admissions. Due to the small sample size, alpha was relaxed to .15 for inclusion in the overall model (42,43). Predictors with p values greater than .05 and less than or equal to .15 are suggested areas for further study.

Results

Hospitalization and incarceration

Declines in hospitalization and incarceration rates for some clients were deceptive. Some clients who remained out of the hospital after entering the program were actually in a correctional facility, and some who avoided incarceration were admitted to hospitals. Data for these clients were merged in the category "institutional admissions." Pooling data reduced negative and positive skew, normalizing distribution.

To provide support for pooling data for clients who were hospitalized or incarcerated, admissions to hospitals and to jails were examined for each client during two years before program entry and for the years in the program. For both periods, the same 57 clients (70 percent) had a mixture of hospitalizations and incarcerations. Twenty-four clients (30 percent) had only hospital admissions, with no incarcerations. For the 57 clients who had both hospitalizations and incarcerations, 30 percent were incarcerations and 70 percent were hospitalizations during the period before program entry. These percentages shifted slightly after program entry—34 percent were incarcerations and 66 percent were hospitalizations. Clients with both hospitalizations and incarcerations did not differ significantly in length of time in the program from those with hospitalizations only (means of 27 and 26 months, respectively).

Because most clients in the program shifted between psychiatric and criminal justice facilities, and such shifting has been documented in the literature (27,28,29,30,31,32,38), pooling data for clients who were hospitalized or incarcerated into the category of institutional admissions appeared to present a more accurate picture of admission rates to both types of facilities.

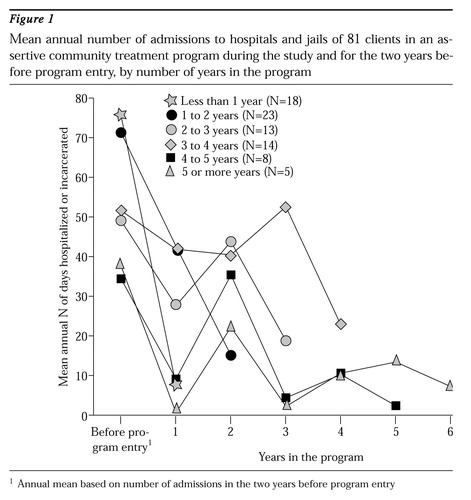

Figure 1 depicts the annual mean number of institutional admissions for the 81 clients in the program, including the mean number for the two years before program entry. Clients in the program for less than one year showed a significant decline in admissions, from 75.57±113.23 to 7.56±11.74 admissions (t=-2.50, df=17, p<.02). For clients in the program between one and two years, repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant decline in institutional admissions (F=4.50, df=2,21, p<.02), specifically between year 1 and 2 (from 42.61±52.89 to 15.09±19.58 admissions; t=-2.46, df=22, p<.02). For clients in the program between one and two years, a significant decline in admissions was also noted between the preprogram period and year 2 of the program (from 71.27±91.37 to 15.09±19.58 institutional admissions; t=-2.86, df=22, p<.01).

It should be noted that the group that had been in the program less than a year and the group that had been in the program between one and two years entered the program with the highest institutional admission rates and were discharged more often than clients in other groups. Six clients in each group were discharged, mostly for refusing treatment. One client in each group died.

For clients in the program between two and three years, the repeated-measures ANOVA did not indicate a significant change in institutional admission rates; however, univariate analyses indicated a trend toward a significant decline in admissions (p<.07) when the preprogram period was compared with year 3 of the program (from 49.08±55.48 to 18.77±24.79 admissions). Admissions rose for this group between year 1 and year 2 of the program and then declined; however, neither of these changes were significant.

Clients in the program between three and four years had significant changes in institutional admissions (F=11.02, df=4,10, p<.001), specifically when year 4 of the program was compared with the preprogram period (22.71±41.26 versus 51.61±41.23 admissions; t=-5.05, df=13, p<.001). No significant year-to-year changes in institutional admissions were noted for this group; a nonsignificant increase was noted between years 2 and 3. Only three of the clients in this group were discharged—between the second and the fourth year. All three were transferred to long-term-care facilities. One client died.

For clients in the four- to five-year group and those with five or more years in the program, the small sample sizes hampered comprehensive analyses. Univariate analyses were conducted, and the results should be interpreted with caution. For clients in the four- to five-year group, institutional admissions increased significantly between year 1 of the program and year 2 (from 9.13±116.92 to 35.38±40.87 admissions; t=2.32, df=7,p<.05) and then declined significantly between year 2 and year 3 (from 35.38±40.87 to 4.38±5.21; t=-2.37, df=7, p<.05). No other significant year-to-year findings were noted for these clients.

For clients with five or more years in the program, no year-to-year changes were significant, although a decline from the preprogram period and year 1 approached significance (37.64± 34.75 to .60±1.34 admissions; p<.07). As Figure 1 shows, this group followed a similar pattern to that of clients in the four- to five-year group. None of the clients in these two groups were discharged; one in each group died. For both groups, the number of admissions in the period before program entry was half the number for clients in the two groups with less than two years in the program.

A separate analysis examined data for the group as a whole. Overall admissions significantly declined from the period before program entry to year 1 (N=81; t=-3.76, df=80, p<.001), to year 2 (N=63, t=-2.73, df=62, p<.01), to year 3 (N=40; t=-2.14, df=39, p<.05), to year 4 (N=27; t=-4.34, df=26, p<.001), and to year 5 (N=13; t=-2.48, df=12, p<.05). For the five clients who had been in the program for six years, the preprogram number of admissions did not differ significantly from the number in year 6.

Clinicians' and clients' perspectives

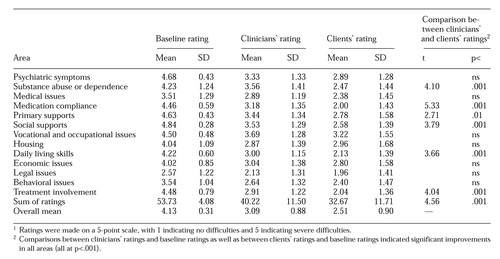

Table 2 shows the clients' and clinicians' ratings of clients' difficulties in all 13 quality-of-life areas and the baseline ratings that were based on those of the program director and the first author. Comparisons using paired t tests indicated that all clients showed significant improvements in all areas (p<.001), both from the clients' and the clinicians' perspectives. The magnitude of improvement differed in six areas in which clients rated themselves as having significantly less current difficulty than clinicians did. The six areas were substance abuse, medication compliance, primary supports, social supports, daily living skills, and treatment involvement.

Predictors of declines in admissions

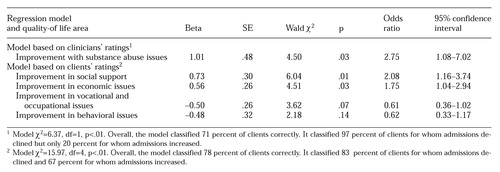

Separate analyses examined whether progress scores, which were calculated by subtracting the baseline rating in each area from the current ratings, were associated with reductions in admissions to hospitals and jails. The scores were applied as potential predictors in a stepwise logistic regression with backward elimination (likelihood ratio criterion). Table 3 summarizes results of the regression analyses.

Although the analyses shown in Table 2 indicated that clients improved over baseline ratings in all 13 quality-of-life areas from the perspective of both the clients and the clinicians, the regression analysis found no significant differences in institutional admissions when controlling for years in the program. The decline or increase in admissions was computed by subtracting the client's mean number of admissions while in the program from the mean annual number of admissions for the two years before program entry, controlling for the number of years in the program.

Clinicians' perspectives. When progress scores based on the clinicians' ratings were used, significant results were realized at step 13 of the logistic regression. As shown in Table 3, only the progress score for substance abuse predicted admissions. In this logistic regression model, improvement in the area of substance abuse correctly classified 97 percent of clients for whom admissions declined but only 20 percent of clients for whom admissions increased—and substance abuse issues worsened. The overall predictive accuracy of the model was 71 percent.

Clients' perspectives. In the logistic model of progress scores based on clients' ratings, significant results were realized at step 10. Progress scores in only two areas—social support and economic issues—were significant predictors of declines in institutional admissions. Progress scores in two other areas—behavioral and vocational-occupational issues—contributed to the model, predicting increases in admissions. However, these two areas only approached significance, and they are likely variables that warrant further study with larger samples. In this regression model, social support and economic improvement correctly classified 83 percent of clients for whom admissions declined and 67 percent of clients for whom admissions increased (when these issues worsened). The overall predictive accuracy of the model was 78 percent.

Discussion and conclusions

Consistent with previous research, this study found that institutional admissions were reduced after admission to an assertive community treatment program. Significant reductions were realized early for all clients, often in the first treatment year, even for clients who had been in the program only six months. For clients in the program for up to two years, the reductions in admissions were largest. However, compared with clients who had been in the program longer, these clients had the largest number of admissions before they entered the program. During the two years before entry, they spent about 20 percent of each year in either psychiatric or correctional facilities.

Of the 81 clients who received services since the program's inception, 15 were discharged and five died. Twelve of the discharges (80 percent) occurred during the first two years in the program, most often because the client refused treatment or was transferred to a structured setting. These 12 discharged clients were admitted between early 1996 and late 1997, while the remaining three clients (20 percent) were admitted between early 1994 and late 1995. The large numbers of institutional admissions and the relatively high discharge rates among the more recent admissions may indicate that these clients spent a considerable amount of time out of the community in hospitals and jails before entering the program and thus required more assistance.

Typically, for clients in the program longer than two years, admissions fluctuated markedly in year 2 or 3 before declining in year 3 or 4. These clients were discharged less often than those who were in the program for less than two years, and their admission rates were lower before entering the program, supporting the idea that clients who spend a substantial amount of time in institutions need additional help to re-enter the community. Discharges of clients who had spent more than two years in the program typically involved transfer to a structured setting rather than treatment refusal.

Overall, our data indicated that clients who had been in the program for five or six years (early admissions) had the greatest improvement in year 3, while those in treatment for between three and four years (more recent admissions) required slightly more time to show progress. These findings are likely attributable to the long period necessary for individuals with severe psychiatric disabilities to establish trust with providers before significant improvement can be realized. A previous long-term study that compared ACT clients with a control group showed similar improvements in client functioning and independent living at roughly the three-year mark, as indicated by follow-up evaluations at 30 and 66 months (44). In the study reported here, new clients showed rapid improvement. However, it remains to be seen whether these individuals experience the same fluctuating recidivism pattern in their second or third treatment year.

Also consistent with previous findings for ACT programs, the clients in this study showed significant measurable improvement in all 13 areas measured—psychiatric symptoms, substance use and abuse, medical issues, medication compliance, primary supports, social supports, vocational and occupational issues, housing, daily living skills, economic condition and entitlements, legal involvement, behavioral issues, and treatment involvement. However, clients rated themselves as having less difficulty than their clinicians thought they had in the areas of substance abuse, medication compliance, primary supports, social supports, daily living skills, and treatment involvement.

Meaningful improvements occurred in clients' quality of life in all areas. However, the discrepancies between the clients' and the clinicians' ratings suggest that improvements in some areas were more meaningful to the clients than to their clinicians. This finding is important in treatment planning. It also highlights the fact that clinicians may overlook the smaller incremental steps toward improvement that are valued by clients.

Declines in institutional admissions were associated with progress in different areas depending on whether the progress scores were based on clinicians' or clients' ratings. According to clinicians, declines were associated with improvements in substance abuse issues. Based on clients' ratings, improvements in social support and economic issues predicted declines in admissions. Other studies, although not of ACT programs, have noted differences in clinicians' and clients' views of treatment planning (45) and evaluation of treatment outcome (46,47). More important, some studies have shown that such discrepancies have resulted in treatment refusal (48,49).

It is difficult to draw conclusions about areas for future research from these findings of differences between clients and clinicians. However, given that most ACT clients fail in more traditional treatment and that they may be more inclined than other clients to drop out of treatment, concordance between their goals and clinicians' goals may be relevant in forming a therapeutic relationship, which often takes years to develop.

The qualitative data gathered during the study about reasons for admission provided some insight into the quantitative findings. In most cases, clinicians' cited external factors, particularly the consequences of clients' substance use. These factors included disinhibition, physical altercations, verbal threats, drug-related legal charges, and avoidance of legal consequences. In contrast, the majority of clients cited psychiatric symptoms. Although these symptoms were clearly exacerbated by heavy substance use, clients appeared to lack sufficient insight to comprehend the consequences of substance abuse and thus minimized it as a reason for being hospitalized or incarcerated and externalized the blame. Also, for many clients, substance use seemed to be a coping mechanism—the only way to "make problems go away."

Many clients who frequented institutional settings were well aware that hospitals are legally required to admit those who present a danger to self or others. Several clients who were admitted as suicidal later acknowledged their "resourcefulness," stating that they were homeless and had nowhere else to go or lacked money for food and other essentials. Several admitted spending their funds on illicit substances, and others refused to stay at local shelters if they found themselves suddenly without accommodations. Also noteworthy, many clients preferred jail to a psychiatric facility, because they had more friends there, had more control and freedom, and felt they were not treated as if they were "crazy." The views and experiences of these clients shed light on the need for adequate financial resources for necessities, the importance of social connections, and stigmatization of persons with mental illness and provide direction for further research.

This study found that ACT clinicians and their clients may have different agendas for client improvement in some areas. Moreover, clinicians and clients may measure improvement differently. Clinicians may not credit clients with small steps toward goals, or they may have higher expectations than are attainable. In addition, clinicians may focus on a difficult treatment issue before alternate provisions are in place. For instance, targeting substance abuse is likely to leave a client without a coping mechanism for stress and without a social network, and most clients have few appropriate interpersonal skills to make new connections.

Furthermore, many services for ACT clients require them to be drug free before participation, especially housing programs, vocational and occupational training, and socialization sites. Although the negative consequences of substance use among these clients are well recognized, perhaps an interim level of services is needed to assist them in making a transition to a drug-free lifestyle. Reasonable expectations and achievable goals during this time may make the transition possible.

The qualitative data complement quantitative findings and enhance understanding of factors contributing to institutional admissions of clients with severe mental illness. Better understanding may enable clinicians to provide interventions appropriate for clients who have failed to use traditional modes of treatment.

Although the results of this study are promising, it has some limitations. First, the study used self-reported measures of difficulty and improvement in the quality-of-life areas. Clinicians and clients may have exaggerated clients' improvements and denied their difficulties, or vice versa. Self-reports are also subject to social desirability and response bias (the tendency to agree or disagree with all items). However, use of a peer counselor to conduct the interview can establish a sense of trust and reduce anxiety (50). Clients may be more honest with a peer interviewer, and the interviewer may be less biased than a nonpeer.

Second, the sample may not be representative of the population of persons with severe mental illness, and thus the results may have limited generalizability. For example, of the 61 clients in the program, 16 refused to be interviewed, and thus their progress, or lack of progress, was not taken into account. Finally, the findings should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of participants. Nevertheless, the findings appear to be consistent with those of previous studies of the effectiveness of assertive community treatment for individuals with severe psychiatric disabilities, and they point to new directions for future research.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Rick Lowe for conducting the interviews.

When this work was done, Dr. Lang was affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine. She is now senior research analyst at the New York City Criminal Justice Agency, 52 Duane Street, New York, New York 10007 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Davidson, Ms. Bailey, and Mr. Levine are affiliated with Yale University School of Medicine and with the Connecticut Mental Health Center in New Haven.

Figure 1. Mean annual number of admissions to hospitals and jails of 81 clients in an assertive community treatment program during the study and for the two years before program entry, by number of years in the program

1 Annual mean based on number of admissions in the two years before program entry

|

Table 1. Characteristics of clients of an assertive community treatment program who participated in a survey about their quality of life, who refused to participate, and who were discharged or decreased at the time of the survey

|

Table 2. Ratings by clinicians and clients' current difficulties in 13 quality-of-life areas and ratings in these areas made at program entry (baseline) by others1

|

Table 3. Results of logistic regression analyses examining whether progress scores based on clinicians' ratings and clients' ratings in 13 quality-of-life areas predicted reductions in admissions to hospitals and jails

1. Stein LI, Test MA: An alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392-397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Burns BJ, Santos AB: Assertive community treatment: an update of randomized trails. Psychiatric Services 46:669-675, 1995Link, Google Scholar

3. Dincin J, Wasmer D, Witheridge TF, et al: Impact of assertive community treatment on the use of state hospital inpatient bed-days. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:833-838, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Essock SM, Kontos N: Implementing assertive community treatment teams. Psychiatric Services 46:679-683, 1995Link, Google Scholar

5. Jansen A, Masterton T, Norwood L, et al: Harbinger Team IV: assertive community treatment for people with the dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance abuse. Innovations and Research 1(2):11-17, 1992Google Scholar

6. Klinkenberg WD, Calsyn RJ: Predictors of receipt of aftercare and recidivism among persons with severe mental illness: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:487-496, 1996Link, Google Scholar

7. Olfson M: Assertive community treatment: an evaluation of the experimental evidence. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:634-641, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Scott JE, Dixon LB: Assertive community treatment and case management for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:657-668, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Rosenheck R, Neale M, Leaf P, et al: Multisite experimental cost study of intensive psychiatric community care. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:129-140, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Quinlivan R, Hough R, Crowell A, et al: Service utilization and costs of care for severely mentally ill clients in an intensive case management program. Psychiatric Services 46:365-371, 1995Link, Google Scholar

11. Santos AB, Hawkins GD, Julius B, et al: A pilot study of assertive community treatment for patients with chronic psychotic disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:501-504, 1993Link, Google Scholar

12. Santos AB, Deci PA, Lachance KR, et al: Providing assertive community treatment for severely mentally ill patients in a rural area. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:34-39, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Taube CA, Morlock L, Burns BJ, et al: New directions in research on assertive community treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:642-647, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Wolff N, Helminiak TW, Morse GA, et al: Cost-effectiveness evaluation of three approaches to case management for homeless mentally ill clients. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:341-348, 1997Link, Google Scholar

15. Lafave HG, deSouza HR, Gerber GJ: Assertive community treatment of severe mental illness: a Canadian experience. Psychiatric Services 47:757-759, 1996Link, Google Scholar

16. Bond GR, Witheridge TF, Dincin J, et al: Assertive community treatment for frequent users of psychiatric hospitals in a large city: a controlled study. American Journal of Community Psychology 18:865-891, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kent S, Yellowlees P: Psychiatric and social reasons for frequent rehospitalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:347-350, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Casper ES, Pastva G: Admission histories, patterns, and subgroups of the heavy users of a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Quarterly 61:121-135, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Mezzich JS, Coffman GA: Factors influencing length of hospital stay. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:1262-1270, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar

20. Postrado LT, Lehman AF: Quality of life and clinical predictors of rehospitalization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:1161-1165, 1995Link, Google Scholar

21. Turner JT, Wan TT: Recidivism and mental illness: the role of communities. Community Mental Health Journal 29:3-14, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. McGrew JH, Wilson RG, Bond GR: Client perspectives on helpful ingredients of assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19(3):13-21, 1996Google Scholar

23. Neale MS, Rosenheck RA: Therapeutic alliance and outcome in a VA intensive case management program. Psychiatric Services 46:719-721, 1995Link, Google Scholar

24. Rosenheck R, Lam JA: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381-386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

25. Dixon L, Friedman N, Lehman A: Compliance of homeless mentally ill persons with assertive community treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:581-583, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

26. Meisler N, Blankertz L, Santos AB, et al: Impact of assertive community treatment on homeless persons with co-occurring severe psychiatric and substance use disorders. Community Mental Health Journal 33:113-122, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Lamb RH, Weinberger LE: Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483-492, 1998Link, Google Scholar

28. Torrey EF: Economic barriers to widespread implementation of model programs for the seriously mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:526-531, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

29. Torrey EF, Stieber J, Ezekiel J, et al: Criminalizing the seriously mentally ill: the abuse of jails as mental hospitals. Innovations and Research 2:11-14, 1993Google Scholar

30. Lamb HR, Shaner R: When there are almost no state hospital beds left. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:973-976, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

31. Treffert DA: Legal "rites": criminalizing the mentally ill. Hillside Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 3:123-137, 1981Medline, Google Scholar

32. Whitmer GE: From hospitals to jails: the fate of California's deinstitutionalized mentally ill. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 50:65-75, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Abram KM, Teplin LA: Co-occurring disorders among mentally ill jail detainees: implications for public policy. American Psychologist 46:1036-1045, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Teplin LA: Psychiatric and substance abuse disorders among male urban jail detainees. American Journal of Public Health 84:290-293, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Outcasts on Main Street: A Report of the Federal Task Force on Homelessness and Severe Mental Illness. NIMH publication ADM 92-1904. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1992Google Scholar

36. Valdiserri EV, Carroll KR, Hartl AJ: A study of offenses committed by psychotic inmates in a county jail. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:163-166, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

37. Steadman HJ, Barbera SS, Dennis DL: A national survey of jail diversion programs for mentally ill detainees. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1109-1113, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

38. Belcher JR: Are jails replacing the mental health system for the homeless mentally ill? Community Mental Health Journal 24:185-195, 1988Google Scholar

39. Solomon P, Draine J: One-year outcomes of a randomized trial of case management with seriously mentally ill clients leaving jail. Evaluation Review 19:256-273, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Wolff N, Diamond RJ, Helminiak TW: A new look at an old issue: people with mental illness and the law enforcement system. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:152-165, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Chinman M, Allende M, Bailey P, et al: Therapeutic agents of assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Quarterly, in pressGoogle Scholar

42. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression. New York, Wiley, 1989, p 108Google Scholar

43. Menard S: Applied Logistic Regression Analysis. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1995, p 106Google Scholar

44. Mowbray CT, Collins ME, Plum TB, et al: Harbinger I: the development and evaluation of the first PACT replication. Administrative and Policy in Mental Health 25:105-123, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Neistadt ME: Methods of assessing clients' priorities: a survey of adult physical dysfunction settings. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 49:1428-1436, 1995Google Scholar

46. Fester AR: Goal attainment and satisfaction scores for CMHC clients. American Journal of Community Psychology 7:181-188, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Llewelyn SP: Psychological therapy as viewed by clients and therapists. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 27:223-237, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Santiago JM, Berren MR, Beigel A, et al: The seriously mentally ill: another perspective on treatment resistance. Community Mental Health Journal 26:237-244, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. McGonagle IM, Gentle J: Reasons for non-attendance at a day hospital for people with enduring mental illness: the clients' perspective. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 3:61-66, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Dixon L, Krauss N, Lehman A: Consumers as service providers: the promise and challenge. Community Health Journal 30:615-625, 1994Google Scholar