One-Year Follow-Up of Day Treatment for Poorly Functioning Patients With Personality Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study evaluated the effectiveness of day treatment for poorly functioning patients with personality disorders who participated in day treatment consisting of analytically oriented and cognitive-behavioral therapy groups as part of a comprehensive group therapy program. METHODS: At admission, discharge, and one year after discharge, patients completed the Global Severity Index (GSI) of the Symptom Check List 90-R and the circumplex version of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP-C) and were assessed using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale. At one-year follow-up, patients also completed a questionnaire covering social adaptation and clinical information and participated in a telephone interview with a clinician. The clinician used the completed instruments and results of the interview to assign patients follow-up GAF scores. RESULTS: Follow-up data were available for 96 patients who completed the study, or 53 percent of the patients who were admitted to the study. Improvements in GAF, GSI, and IIP-C scores during day treatment were maintained at follow-up. Seventy-four percent of the treatment completers improved clinically from program admission to follow-up, as indicated by change in GAF scores, and 64 percent of the treatment completers continued in the outpatient group program. For the 26 percent of patients whose change in GAF score did not indicate clinical improvement, lack of improvement was most strongly predicted by the expression of suicidal thoughts during treatment. No patients committed suicide. CONCLUSIONS: The day treatment program appears to be effective in improving the symptoms and functioning of poorly functioning patients with personality disorders and in encouraging patients to continue in longer-term outpatient therapy.

Several studies have shown that psychosocial treatment may lead to significant improvement in the symptoms, distress, and general functioning of patients with personality disorders, and such findings represent a correction to the pessimism often associated with attempts to treat moderate and severe personality pathology (1,2,3,4,5,6,7). However, more information is needed about optimal treatment approaches and levels of care for various groups of patients with personality disorders (8).

In the study reported here, we conducted a prospective, naturalistic one-year follow-up of patients treated in a group-oriented day treatment program for personality disorders at a university hospital in Oslo, Norway. The program is described in more detail elsewhere (9). The purpose of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the day treatment program for these patients.

The 18-week day treatment program—the first part of a comprehensive group psychotherapy program—consists of a combination of analytically oriented and cognitive-behavioral therapy groups (4,10,11). The second part consists of long-term analytically oriented outpatient group psychotherapy (11) with a time limit of three and a half years. The treatment is described in a previous paper in which we reported an acceptable rate of completion of the day treatment program (75 percent), a low frequency of complications, and overall positive change for treatment completers in a cohort of poorly functioning patients (9).

The study reported here presents results for the same cohort. In this report we focus on the patients' global functioning, subjective distress, interpersonal problems, and work status at follow-up and on their rate of hospitalizations, suicidal behavior, and substance abuse during the follow-up period. In addition, we examined the rate of patients' continuation in the outpatient group program, the rate of noncontinuation, and the characteristics of the patients who did not improve.

Methods

Assessments

All patients admitted to the day treatment program during the period from 1993 to 1996 who provided informed consent were included in the study. Several instruments were used in assessments made by the therapist team at admission and discharge from the day treatment program: the Longitudinal Expert All Data (LEAD) standard for assessing DSM-III-R and DSM-IV axis II disorders (12,13), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R for assessing axis I disorders (13), the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale (14), the Global Symptom Index derived from the Symptom Check List 90-R (SCL-90-R) (15), and the Index of Interpersonal Problems, circumplex version (IIP-C) (16). The therapists filled in a data form covering sociodemographic information, as well as information on childhood trauma, previous symptoms, work functioning, and previous and current treatment.

One year after the patients were discharged, the SCL-90-R, the IIP-C, and a questionnaire covering social adaptation and clinical information were mailed to all patients. Patients indicated on the forms they returned whether they agreed to be called for an interview by a therapist from the day treatment program. Based on this interview and information from the questionnaires, the therapist assigned each patient a GAF score. The National Death Register was checked for cases of suicide.

Data analysis

Differences in scores between patients who had improved and those who had not improved in the day treatment program were tested using the chi square test, Fisher's exact test, and t tests for independent samples. Paired t tests and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests were used for paired observations. Logistic regression analyses were used to make a model for predicting nonresponse to treatment. Because of missing values, the analyses have small variations in the total number of subjects.

Subjects

A total of 183 patients admitted to the day treatment program gave informed consent to participate. Due to administrative error, the follow-up questionnaires were not mailed to 24 patients, or 13 percent of the total. Data were available for 117 subjects, or 64 percent of the total sample. Twelve of those subjects, who did not want to be interviewed by phone, were given a GAF score on the basis of information from the questionnaires only. Patients were considered to have completed the day treatment program if they had completed a minimum of 17 weeks of treatment and were discharged with the agreement of the therapist team.

Seventy percent of 138 subjects who completed the day treatment program participated in the follow-up, compared with 47 percent of 45 noncompleters, a significant difference (χ2=7.72, df=1, p<.01). Subjects who did not participate in the follow-up had a significantly lower mean GAF score at discharge of 47.5, compared with 51.3 for those who participated in the follow-up (t=-2.91, df=181, p<.01). Subjects who participated in the follow-up were more likely to show self-mutilating behavior during their stay in the day treatment program (11 percent, compared with 2 percent for those who did not participate in the follow-up; χ2=5.50, df=1, p<.05). The groups did not differ significantly on other clinical variables or in sex or age.

The results are based on data for the 96 subjects, or 82 percent of the original group, who completed day treatment. Seventy-six percent were female. At admission, their mean age was 33±8 years, 32 percent were married or cohabiting, 66 percent were not functioning at work or school or were unemployed, 37 percent had previously attempted suicide, and 43 percent had previous hospitalizations.

After the final evaluation, 85 percent received one or more personality disorder diagnoses. Subjects had a mean of 1.6±.9 personality disorders. The most frequently occurring were avoidant personality disorder for 39 percent of subjects, borderline for 35 percent, personality disorder not otherwise specified for 19 percent, dependent for 16 percent, and paranoid for 8 percent. Ninety-nine percent of the subjects had axis I disorders. Seventy-five percent had one or more mood disorders, 57 percent had one or more anxiety disorders, 18 percent had an eating disorder, and 15 percent had substance use disorders.

Results

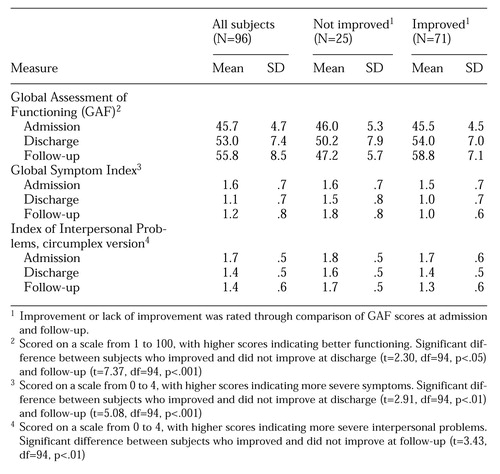

As Table 1 shows, mean GAF scores for all 96 subjects showed a small but significant improvement from discharge to follow-up. In addition, changes in GSI and IIP-C scores during the day treatment program were maintained at follow-up.

Sixty-six subjects, or 69 percent, were engaged in work or studies at follow-up. Eight subjects, or 8 percent, were hospitalized during the follow-up period; they remained in the hospital for a median of 3.5 weeks, with a range from less than one to 35 weeks.

None of the patients committed suicide. Four subjects made suicide attempts during the follow-up period; the median number of suicide attempts was one, with a range from one to two. However, 31 patients, or 32 percent, had been troubled by suicidal ideation. Problems with excessive substance use during the follow-up period were reported by 20 subjects, or 21 percent. Sixty-five subjects, or 68 percent, reported less mental distress at follow-up compared with discharge; 19 patients, or 20 percent, reported no change; and 12 patients, or 13 percent, had become worse.

Sixty-one subjects, or 64 percent, continued in the long-term outpatient group psychotherapy program. Nineteen of those subjects, or 31 percent, received combined group and individual therapy. Sixteen subjects among the day treatment completers, or 17 percent, did not receive any psychiatric outpatient treatment after discharge, although some received medication from general practitioners. Nineteen subjects, or 20 percent, continued in other outpatient treatment programs; 12 of them participated in individual therapy, four in group therapy, and three in other types of therapy.

The patients who continued in the program's analytically oriented outpatient therapy, those who received no outpatient treatment, and those who participated in other types of therapy showed no significant differences in sporadic or regular use of psychotropic medications. The 12 patients who had a cluster A personality disorder were less likely to attend the long-term outpatient group program. Three subjects with cluster A personality disorder, or 25 percent, attended the long-term group program; six subjects, or 50 percent, started in other types of treatment; and three subjects, or 25 percent, received no outpatient treatment (Fisher's exact test=9.57, p<.01).

The patients were categorized as improved or not improved according to the level of GAF at admission and follow-up. Subjects were categorized as improved when the increase in GAF score was one standard deviation or more from the admission score for the total sample, that is, 5 points on the GAF scale. Furthermore, the GAF score at follow-up had to be equal to, or above, 45. Seventy-one of the 96 treatment completers, or 74 percent, were categorized as improved, compared with five of the 21 noncompleters, or 24 percent (χ2=19.04, df=1, p<.001). Among the patients who were improved at follow-up were 46 of the 61 patients who continued in the program's analytically oriented outpatient therapy, or 75 percent; 13 of the 16 patients who received no outpatient treatment after discharge from day treatment, or 81 percent; and 12 of the 19 patients who participated in other types of therapy, or 63 percent. Table 1 shows the mean GAF, GSI, and IIP-C scores for the patients who were improved at follow-up and those who were not improved.

We examined several demographic, historical, and clinical variables for possible differences between the outcome groups. The demographic variables were age, sex, marital status, education, and work functioning. Historical variables included physical or sexual abuse, early loss, and parents' divorce. Clinical variables included previous suicidal behavior, self-mutilation, or other behavioral dyscontrol; amount of previous treatment; history of hospitalization; age at first treatment; GSI, IIP-C, and GAF scores at admission to the day treatment program; suicidal behavior, self-mutilation, and other behavioral dyscontrol during the program; regularity of attendance; use of medication; personality disorder cluster; presence of borderline, avoidant, or paranoid personality disorder; number of personality disorders; and concurrent mood, anxiety, eating, or substance use disorders.

Subjects who did not improve were more likely to have experienced the loss of a significant other before the age of ten (20 percent, compared with 4 percent of subjects who improved; Fisher's exact test=5.37, p<.05). In addition, subjects who did not improve more often expressed intentions of self-mutilation (25 percent, compared with 7 percent of those who improved; Fisher's exact tests=4.94, p<.05) and were more likely to self-mutilate during day treatment (24 percent, compared with 6 percent of those who improved; Fisher's exact test=5.98, p<.05). They were also more likely to express suicidal ideation during day treatment (48 percent, compared with 13 percent of those who improved; N=94; χ2=12.27, df=1, p<.001).

Variables that showed between-group differences at the probability level of p<.10 in the bivariate analyses were explored in logistic regression analyses in which improvement or lack of improvement was the dependent variable. The best predictive model consisted of one variable: the expression of suicidal ideation during the day treatment program predicted 11 of the 23 cases in which subjects were not improved (odds ratio=6.11, 95 percent confidence interval=2.08 to 17.94, p<.01). The sensitivity of the model was .48; the specificity was .87.

The two outcome groups did not differ significantly on the SCL-90-R depression subscale (mean scores of 2 and 2.2) or the SCL-90-R suicidal thoughts item (mean scores of .8 and 1) at admission. However, the group that improved experienced a significant reduction in mean depression score, from 2 at admission to 1.4 at discharge (t=6.36, df=70, p<.001), and in mean score on the suicidal thoughts item, from .8 at admission to .4 at discharge (z=2.83, p<.01). The reduction in depression for subjects who did not improve, from a mean score of 2.2 at admission to 1.9 at discharge, was not significant. A nonsignificant increase in mean scores on the suicidal thoughts item, from 1 at admission to 1.3 at discharge, was noted for this group.

Discussion

Subjects' overall maintenance at one-year follow-up of positive changes during the day treatment program is in line with two other studies of specialized day treatment programs for personality disorders (4,17), as well as other treatment modality studies (3,5,6,18), showing that treatment gains can be sustained after the end of treatment. We do not know the significance of the follow-up treatment for the maintenance of the changes. The findings indicate that some patients do reasonably well with day treatment only. Most patients, however, experienced a need for further treatment after discharge, which is consistent with the philosophy of the two phases of the treatment model. There seems to be an increasing recognition that patients with severe personality disorders may require follow-up treatment to consolidate gains from treatment in more intensive programs (8,19).

The question of whether short- or intermediate-term treatments may lead to structural changes among patients with severe personality disturbances is still unsettled (1). The improvements in this study may reflect remission or partial remission of axis I disorders, which were not assessed at follow-up. However, considering the tendency for relapse and poor treatment response for concurrent axis I disorders (20,21), stabilization of axis I symptoms at a lower level may be regarded as a useful outcome.

As most studies do not report treatment failures, a 26 percent nonresponse rate is difficult to compare, but it may be acceptable for this category of patients, who are known to be difficult to treat. The bivariate analyses and an alternative, less precise multivariate model, suggested a prognostic influence of early loss. However, neither diagnoses nor other background variables predicted outcome. This result may be due to limitations of the study. First, the definition of the outcome groups used in this study may not have captured clinically significant groups. Dichotomized outcomes imply lost variance and marginal cases. Subjects who did not improve in global functioning may have improved in global symptoms, and vice versa. Second, patients' characteristics such as psychological mindedness and quality of object relations, which have been found to be predictive of outcome (22,23), were not assessed in the study. Third, categorical diagnoses may be insufficient for the prediction of treatment outcome. Some empirical evidence has suggested that dimensionally assessed diagnoses may capture dimensions of severity of illness that are of prognostic value (20,24,25). Moreover, dimensional rating of other predictors may also be preferable (26).

The fact that no subjects had committed suicide is remarkable given the high risk of suicide associated with personality disorders and the assumed increased risk of suicide among patients with borderline personality disorder during the first few years after discharge from inpatient treatment (27). Expressing suicidal thoughts during the day treatment program was strongly associated with nonresponse. For these patients, entering the program may not have initially instilled hope, an important therapeutic factor in group therapy (28). Some patients may experience the intensive group program as too overwhelming or not supportive enough. We cannot say if these perceptions reflect treatment processes or patient characteristics, but persistence of suicidal thoughts during the stay should alert the staff to a possible poor match between patient and treatment.

Conclusions

Patients who completed the day treatment component of a comprehensive group therapy program for patients with severe personality disorders overall maintained improvements associated with day treatment at one-year follow-up and had a high rate of continuation in the longer-term analytically oriented outpatient group component of the program. These results confirm the effectiveness of the day treatment component of the program.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Haldis and Josef Andresens Fund and by UllevÅl University Hospital

The authors are affiliated with the division of psychiatry at UllevÅl University Hospital, N-0407 Oslo, Norway (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Mean scores on three measures of functioning and symptoms at admission, discharge, and one-year follow-up for subjects who completed the day treatment component of a comprehensive treatment program for poorly functioning patients with personality disorders

1. Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH: Treatment outcome of personality disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 43:237-250, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, et al: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:1060-1064, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Munroe-Blum H, Marziali E: A controlled trial of short-term group treatment for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders 9:190-198, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Piper WE, Rosie JS, Joyce AS, et al: Time-Limited Day Treatment for Personality Disorders: Integration of Research and Practice in a Group Program. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1996Google Scholar

5. Antikainen R, Hintikka J, Lehton J, et al: A prospective three-year follow-up study of borderline personality disorder inpatients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 92:327-335, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Monsen J, Odland T, Faugli A, et al: Personality disorders and psychosocial changes after intensive psychotherapy: a prospective follow-up study of an outpatient psychotherapy project, 5 years after end of treatment. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 36:256-268, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Mehlum L, Friis S, Irion T, et al: Personality disorders 2-5 years after treatment: a prospective follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 84:72-77, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Links PS: Developing effective services for patients with personality disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 43:251-259, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Wilberg T, Karterud S, Urnes Ø, et al: Outcomes of poorly functioning patients with personality disorders in a day treatment program. Psychiatric Services 49:1462-1467, 1998Link, Google Scholar

10. Foulkes SH, Anthony EJ: Group Psychotherapy: The Psychoanalytic Approach. New York, Penguin, 1957Google Scholar

11. Pines M: Group analytic psychotherapy and the borderline patient, in The Difficult Patient in Groups: Group Psychotherapy With Borderline and Narcissistic Disorders. Edited by Roth BE, Stone WN, Kibel HD. Madison, Conn, International Universities Press, 1990Google Scholar

12. Spitzer RL: Psychiatric diagnosis: are clinicians still necessary? Comprehensive Psychiatry 24:399-411, 1983Google Scholar

13. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, Patient Version. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometric Research, 1988Google Scholar

14. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale, in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

15. Derogatis LR: The SCL-90: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual-II for the Revised Version. Baltimore, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1977Google Scholar

16. Alden LE, Wiggins JS, Pincus AL: Construction of circumplex scales for the inventory of interpersonal problems. Journal of Personality Assessment 55:521-536, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Krawitz R: A prospective psychotherapy outcome study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 31:465-473, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE: Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:971-974, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Norton K, Hinshelwood RD: Severe personality disorder: treatment issues and selection for inpatient psychotherapy. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:723-731, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Ilardi SS, Craighead WE: Modeling relapse in unipolar depression: the effects of dysfunctional cognition and personality disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:381-391, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Alnaes R, Torgersen S: Personality and personality disorders predict development and relapse of major depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 95:336-342, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Piper WE, Joyce AS, Rosie JS, et al: Psychological mindedness, work, and outcome in day treatment. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 44:291-311, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. McCallum M, Piper WE, O'Kelly J: Predicting patient benefit from a group-oriented, evening treatment program. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 47:291-314, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Links PS, Heslegrave R, van Reekum R: Prospective follow-up study of borderline personality disorder: prognosis, prediction of outcome, and axis II comorbidity. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 43:265-270, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Marziali E, Munroe-Blum H, Links P: Severity as a diagnostic dimension of borderline personality disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 39:540-544, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Paris J, Zweig-Frank H, Guzder H: The role of psychological risk factors in recovery from borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry 34:410-413, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Perry JC: Longitudinal studies of personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders 7(suppl):63-85, 1993Google Scholar

28. Yalom ID: The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 3rd ed. New York, Basic Books, 1985Google Scholar