Rural Psychiatry : Functional Impairment Associated With Psychological Distress and Medical Severity in Rural Primary Care Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined functional impairment associated with psychological distress and severity of medical illness in a rural primary care population and explored how functional impairment varied with psychological distress and chronic medical illness. METHODS: Fifty-eight patients recruited from three rural primary care clinics completed the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and the Typology of Psychic Distress (PsyDis). The chronic disease score, a measure of the severity of chronic medical illness, was calculated from data on use of prescription medications over a six-month period. T tests were used to determine the level of functional impairment associated with various levels of psychological distress and medical illness. Regression analyses were used to determine the proportion of variance in impairment that was explained by level of psychological distress and severity of medical illness. RESULTS: High levels of psychological distress explained the variance in impairment in several domains measured by the SF-36, including general health, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health, whereas a high level of severity of chronic medical illness explained the variance in impairment in physical functioning. Both high psychological distress and high severity of chronic medical illness explained the variance in impairment in vitality, and neither variable explained variance in impairment in physical role or bodily pain. CONCLUSIONS: In this rural outpatient primary care population, functional impairment was explained more by psychological distress than by severity of medical illness. Decreasing the burden of psychological distress among primary care patients may improve functioning.

Rural areas, in spite of their pastoral image, have a prevalence of psychiatric disorder similar to urban areas (1,2,3). However, people in rural areas tend to have less access to health care, and in many cases the care they receive is provided solely by primary care clinics.

Several epidemiological studies have shown that primary care populations have a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders than do community populations (2,3,4). Even when mental health resources are available, most patients with affective, anxiety, somatoform, or substance use disorders are seen by primary care providers (5). In one study, even though specialized mental health services were available, 50 to 70 percent of patients with psychiatric disorders were treated in a primary care setting (6). Furthermore, primary care patients have a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders than the general community, and primary care patients with psychiatric illness utilize more health care resources (7,8,9,10).

Recent studies have investigated functional impairment among patients with psychiatric disorders (11,12). In the PRIME-MD study of 1,000 primary care patients, 39 percent had psychiatric disorders, which accounted for more impairment on all domains of the Health-Related Quality of Life index than common medical disorders (12). Furthermore, impairment is a complex phenomenon and is likely created by many variables, not just by the presenting complaint or the illness that may be of primary clinical concern to physicians, whether this condition is medical or psychiatric (13,14,15). That multiple factors are responsible for impairment has been noted for patients with coronary artery disease (16), renal insufficiency (17), and panic disorder (13). It is thus important for the primary care physician to ask himself or herself, "What really ails this particular patient?" Given the limited health care resources in rural areas, answering this question may improve treatment of conditions that are common, impairing, and treatable.

This study had three aims. The first was to determine the prevalence of psychological distress, probable psychiatric illness, and the impairment associated with that distress and illness in a rural primary care population. The second aim was to determine the impairment associated with chronic medical illness. The third aim was to determine how functional impairment varies with psychological distress and severity of chronic medical illness.

Methods

Subjects and instruments

Study participants included patients who presented for primary care appointments at three rural primary care clinics in northern New Mexico over a one-month period in 1996 and who completed a survey during their visit. Although attempts were made to collect data from consecutive attendees, the final sample was one of convenience. The majority of clinic patients are Caucasian-Hispanic, and the clinics serve an economically stressed area. Factors influencing survey completion included primary language, as the survey was in English; literacy; time in the waiting room; and personal inclination, as patients were free to choose whether or not to participate.

Subjects completed two instruments while in the clinic. In some cases, the patients' primary care pro- viders helped with the questionnaires.

The first instrument, the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), was validated in the Health Insurance Experiment and Medical Outcomes Study (18). The SF-36 is a self-report questionnaire that measures respondents' level of functioning in eight domains on a scale from 0, poor, to 100, excellent. The eight domains include physical functioning, or the capacity for physical activities; physical role, or extent of role limitations due to physical problems; social functioning; and bodily pain. The remaining four domains are general mental health; emotional role, or the extent of role limitations due to emotional problems; vitality, or the extent to which the respondent feels tired and worn out or feels full of energy; and general health perceptions, or the respondent's view of his or her level of current and future health.

The second instrument was the Typology of Psychic Distress (PsyDis), a self-report questionnaire with 17 items about self-perceived emotional and cognitive state (19). The PsyDis provides a score indicating a high, medium-high, medium-low, or low likelihood of a diagnosable psychiatric disorder's being present. The PsyDis is divided into four scales that measure the level of depression, anergia, anxiety, and perceived cognitive difficulties.

A third instrument used in the study was the chronic disease score (CDS), a measure of the severity of chronic medical illness derived from the patient's level of use of prescription medications over a six-month period (20). This score has been shown to be stable over a one-year period and has a high correlation with physicians' ratings of severity of medical illness. The CDS has also been found to predict hospitalization and mortality in the year after assessment when the analysis controls for age, gender, and number of health care visits. The CDS was initially validated using automated pharmacy data (20). In this study data on patient's medications were supplied by patients' primary care providers.

Statistical analyses

T tests were used to determine if patients with high and low CDS scores and with high and low PsyDis scores differed on scores for the various domains measured by the SF-36. Pearson correlation analyses were done to determine the association between scores on the SF-36, the full PsyDis, and the PsyDis scales. In addition, for each of the domains of functioning measured by the SF-36, a multiple regression analysis was performed using high and low CDS and high and low PsyDis score as the independent variables.

Results

Patient characteristics

Completed surveys were obtained from 58 subjects. Forty-six subjects, or 79 percent, were female. The average age of the subjects was 46.2±15.4 years. Compared with the population served by the clinics, the study group included a slightly higher proportion of females. More than half the population served by the clinics was in the age range represented by the standard deviation for the mean age of study subjects.

Psychological distress and chronic disease severity

Thirty-four patients, or 58.6 percent, scored high or medium-high in psychological distress. In the analyses patients scoring high or medium-high were grouped together as having a high level of distress. Twenty-nine of the 34 patients, or 85 percent, were female, and five were male. Nine patients, or 16 percent, had a high CDS. This group included five female patients, or 56 percent of the group, and four male patients. Age was not a predictor of high scores on either the PsyDis or the CDS.

Of the 34 patients with high or medium-high psychological distress scores, 27, or 79 percent, had a low CDS, and seven, or 21 percent, had a high CDS. Of the 24 subjects with low or low-medium psychological distress scores, 22, or 92 percent, had a low CDS and two, or 8 percent, had a high CDS.

Psychological distress, chronic disease, and impairment

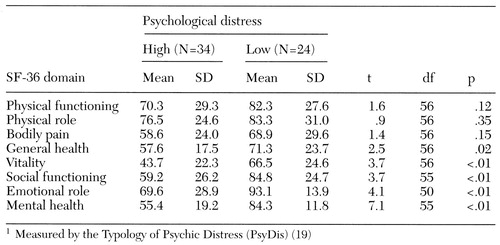

As Table 1 shows, subjects with high psychological distress were significantly more impaired in five of the eight SF-36 domains, compared with subjects with low psychological distress. The five domains were general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health. No significant differences between groups were found for physical functioning, physical role, and bodily pain.

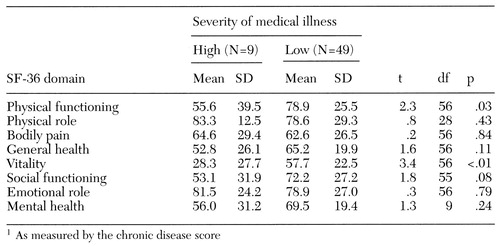

Table 2 shows scores on the eight SF-36 domains for subjects with high and low levels of severity of chronic medical illness, as measured by the CDS. Subjects with a high level of severity had significantly more impairment in three of the eight domains: physical functioning, vitality, and social functioning. Those with a high level of severity also tended to have a worse general health perception than those with a low level. No differences between subjects with high and low levels of severity of medical illness were found for the domains of physical role, bodily pain, emotional role, and mental health.

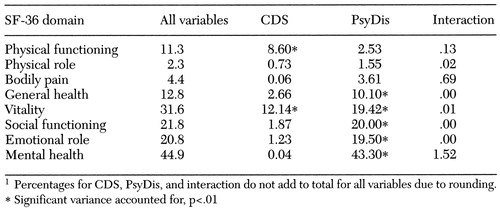

Regression analyses were performed to determine the proportion of the variance (r2) in scores on each impairment domain that was explained by the CDS and PsyDis scores. Table 3 shows the results of a full model regression using the high and low designations for both the CDS and the PsyDis. The table shows two kinds of results—first, the total variance in impairment explained by the CDS and the PsyDis scores together and, second, the variance in impairment explained by either the CDS or the PsyDis scores. The second set of results was determined by a backward elimination process.

As the second set of results shows, a high level of severity of chronic medical illness explained the significant variance in impairment scores for physical functioning and added to the variance in the impairment scores for vitality. On the other hand, a high level of psychological distress explained the significant variance in impairment scores for general health, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health and added to the variance in impairment scores for vitality. Psychological distress and severity of chronic medical illness did not explain significant variance in impairment for physical role or bodily pain.

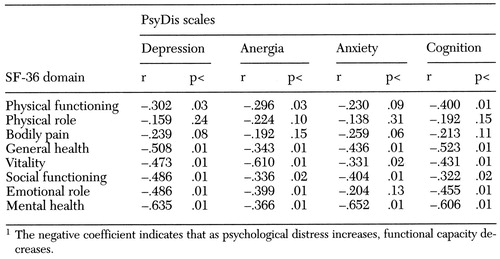

Table 4 shows the correlations between the scales of the PsyDis and the domains of self-rated impairment on the SF-36. A significant correlation was found between the PsyDis scale scores of depression, anergia, anxiety, and cognition problems and the scores for functional impairment in all SF-36 domains except physical role and bodily pain. The correlation was very strong (p<.01) between general health and depression and cognition, between vitality and anergia, between social functioning and depression, between emotional role and depression, and between mental health and depression, anxiety, and cognition.

Discussion

The majority of patients' self-rated functional impairment in general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health in the rural outpatient primary care population we studied was accounted for by the degree of psychological distress and not by the severity of chronic medical illness. On the other hand, the majority of self-rated functional impairment in physical functioning in the same clinic was accounted for by the severity of medical illness and not by psychological distress. However, those with severe medical illness tended to be psychologically distressed as well.

The interaction between psychological distress and chronic medical disease has a synergistic effect on functioning, particularly in the domain of vitality. The strong correlations between the functional impairment domains of the SF-36 and scales of the PsyDis suggest that the association between impairment and psychological distress in primary care is important and complex. In addition, the type of psychological distress experienced by the patient may affect some domains of functioning more than others.

Several factors must be taken into consideration when interpreting the study results. The SF-36 and PsyDis are self-reporting instruments, and their use may result in either under- or overreporting of symptoms and impairment. Sample selection may have been biased due to subjects' primary language, literacy, length of wait at the clinics, and individual inclination to participate. Physical distress during the clinic visit may have influenced whether a survey was completed. The strong association between functional impairment and psychological distress does not indicate a causal relationship, and one cannot conclude that a decrease in psychological distress would improve functioning. Also one cannot conclude that increased availability of traditional mental health services would reduce psychological distress.

The PsyDis and CDS have been validated as proxies for psychiatric disorders and chronic medical illness, respectively (19,20). In the current study the CDS was not determined from automated pharmacy data but from a six-month medication list supplied by physicians. A similar study using psychiatric and medical diagnoses to predict impairment may have different results.

However, our findings support those of other studies that have demonstrated a high burden of distress among primary care patients and increased impairment associated with mood, anxiety, and somatoform disorders, compared with many common medical illnesses (12). It is well established that patients with psychiatric disorders and psychological distress are frequent users of health care services (7,21,22). Social factors such as economic hardship, homelessness, and violence play an important role in psychological distress (23,24). Primary care patients are also significantly impaired by minor illnesses that are common, costly, and rarely understood (25,26).

Addressing the psychological distress associated with impaired functioning in primary care populations requires improved mental health care services in primary care settings. The high prevalence of psychiatric disorders in primary care has been repeatedly established (2,27,28,29), suggesting that at least one in four primary care patients has an impairing psychiatric disorder. Individuals who somatize psychological distress may do so for adaptive purposes, such as to allow occupation of the sick role in settings where psychological distress is stigmatized, to avoid blame, or to decrease the conscious experience of depression (30). The increased reliance on primary care providers in managed care also suggests the need to improve mental health services in primary care settings.

How to decrease the functional impairment associated with psychological distress and psychiatric disorders in primary care settings remains a challenge. To improve detection of psychiatric disorders, Goldberg (14) suggested a model for a brief psychological functioning examination that can be readily taught and used in primary care settings. For management, guidelines have been developed to help primary care providers deal with "persistent complainers" —those who have emotional disorders but present with somatic complaints (31)—and treat patients with psychiatric disorders (15,32).

However, the benefits of the interventions need further study. Katon and Gonzales (33) reviewed psychiatric treatment trials with randomly assigned subjects in primary care and noted that most patient outcomes were relatively unchanged when the goal was to increase mental health care by primary care providers. The exception was outcomes for severely ill patients in the care of well-trained, highly motivated primary care physicians; these patients benefited more, and specific interventions for specific disorders led to decreased medical costs. The authors noted that it is difficult to change physicians' practices, a finding corroborated in a recent study by Carr and colleagues (34).

Provision of mental health services by mental health professionals in the primary care setting is an alternative to changing the practice styles of primary care providers. Nickels and McIntyre (35) described the implementation of such a system in 12 primary care clinics in an urban area; care was provided by traveling therapists overseen by a psychiatrist who provided diagnostic assessment, consultation, and medication recommendations. The outcome of this program remains to be seen. In Williams and Balestrieri's review (36), psychiatric clinics in general practice settings reduced psychiatric admissions, particularly of nonpsychotic patients. However, other studies have indicated that helping primary care providers increase detection of psychiatric disorders alone does not improve patient outcomes (37). When social factors are a strong influence on psychological distress, it may be that broader social changes that affect economic status, substance abuse, and violence have a greater impact than providing individual mental health treatment.

Conclusions

In a rural primary care population, functional impairment was more strongly associated with psychological distress than with severity of medical illness. Decreasing psychological distress by providing mental health services in primary care settings may be a means of improving patients' functioning. However, further studies are needed to determine how effective current mental health services are in improving patients' functioning and to determine how best to implement mental health services to alleviate the considerable burden of psychological distress seen in rural primary care settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Helene Silverblatt, M.D., and E. H. Uhlenhuth, M.D.

When this work was done, Dr. Thurston-Hicks was a psychiatric resident in the department of psychiatry at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque, where Ms. Paine is a biostatistician. Dr. Thurston-Hicks currently is medical director of West Central Mental Health Center in Canon City, Colorado. Dr. Hollifield is assistant professor and director of the special problems and behavioral medicine clinic in the departments of psychiatry and family and community medicine at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 2400 Tucker Avenue, N.E., Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131. Address correspondence to Dr. Hollifield. This paper is one of several on rural psychiatry in this issue.

|

Table 1. Mean scores on domains of the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) of subjects in rural primary care clinics with high and low levels of psychological distress1

|

Table 2. Mean scores on domains of the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) of subjects in rural primary care clinics with high and low levels of severity of chronic medical illness1

|

Table 3. Regression analysis showing proportion of total variance in scores on the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) accounted for by severity of chronic medical illness (CDS), level of psychological distress (PsyDis), and the interaction of CDS and PsyDis, in percentages1

|

Table 4. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) showing relationships between scale scores of the Typology of Psychic Distress (PsyDis) and domains of the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)1

1. Giel R, Van Lujik JN: Psychiatric morbidity in a small Ethiopian town. British Journal of Psychiatry 115:149-162, 1969Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hollifield M, Katon W, Morojele N: Anxiety and depression in an outpatient clinic in Lesotho, Africa. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 24:179-188, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. VonKorff M, Shapiro S, Burke JD, et al: Anxiety and depression in a primary care clinic: comparison of Diagnostic Interview Schedule, General Health Questionnaire, and practitioner assessments. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:152-156, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Katon W, Schulberg H: Epidemiology of depression in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry 14:237-247, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Shapiro S, Skinner EA, Kessler LG, et al: Utilization of health and mental health services: three Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:975-978, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Campbell T, McDaniel S: Branching out: randomized trial of collaborative family health care for distressed high utilizers of the medical system. AFTA (American Family Therapy Academy) Newsletter 10:7-9, 1997Google Scholar

7. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Distressed high utilizers of medical care: DSM-III-R diagnoses and treatment needs. General Hospital Psychiatry 12:355-362, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Katon W, Berg AO, Robbins AJ, et al: Depression: medical utilization and somatization. Western Journal of Medicine 144:564-568, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

9. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al: Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:352-357, 1995Link, Google Scholar

10. Smith GR: The course of somatization and its effects on utilization of health care resources. Psychosomatics 35:263-267, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Klerman GL: Depressive disorders: further evidence for increased medical morbidity and impairment of social functioning. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:856-858, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, et al: Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders: results of the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 274:1511-1517, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hollifield M, Katon W, Skipper B, et al: Panic disorder and quality of life: variables predictive of functional impairment. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:766-772, 1997Link, Google Scholar

14. Goldberg D: Detection and assessment of emotional disorders in a primary-care setting. International Journal of Mental Health 8:30-48, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Hollifield M, Vogel A: The somatizing patient, in Medicine: A Primary Care Approach. Edited by Rubin R, Voss C, Derksen DJ, et al. Philadelphia, Saunders, 1996Google Scholar

16. Sullivan M, La Croix A, Baum C, et al: Functional status in coronary artery disease: a one-year prospective study of the role of anxiety and depression. American Journal of Medicine 103:348-356, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Harris LE, Luft FC, Rudy DW, et al: Clinical correlates of functional status in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. American Journal of Kidney Disease 21:161-166, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al: SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1993Google Scholar

19. Mellinger GD, Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH, et al: Evaluating a household measure of psychic distress. Psychological Medicine 13:607-621, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. VonKorff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K: A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 45:197-203, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Zoccolillo MS, Cloninger CR: Excess medical care of women with somatization disorder. Southern Medical Journal 79:532-535, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Mechanic D: Effects of psychological distress on perceptions of physical health and use of medical and psychiatric facilities. Journal of Human Stress 4:26-32, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Zima BT, Wells KB, Benjamin B, et al: Mental health problems among homeless mothers: relationship to service use and child mental health problems. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:332-338, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Wyshak G, Modest GA: Violence, mental health, and substance abuse in patients who are seen in primary care settings. Archives of Family Medicine 5:441-447, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Komaroff AL: "Minor" illness symptoms: the magnitude of their burden and of our ignorance. Archives of Internal Medicine 150:1586-1587, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kroenke K, Mangelsdorff AD: Common symptoms in ambulatory care: incidence, evaluation, therapy, and outcome. American Journal of Medicine 86:262-266, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Zung WWK: Prevalence of clinically significant anxiety in a family practice setting. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:1471-1472, 1986Link, Google Scholar

28. Katon W: Depression: somatization and social factors. Journal of Family Practice 27:579-580, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

29. Hoeper EW, Nycz GR, Cleary PD, et al: Estimated prevalence of RDC mental disorder in primary medical care. International Journal of Mental Health 8:6-15, 1979Google Scholar

30. Goldberg DP, Bridges K: Somatic presentations of psychiatric illness in primary care settings. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 32:137-144, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Giel R, Workneh F: Coping with outpatients who cannot cope: management of persistent complainers in an African country. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 74:475-478, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Kathol R, Katon W, Smith GR, et al: Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of depression for primary care physicians: implications for consultation-liaison psychiatrists. Psychosomatics 35:1-12, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Katon W, Gonzales J: A review of randomized trials of psychiatric consultation-liaison studies in primary care. Psychosomatics 35:268-278, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Carr VJ, Faehrmann C, Lewin TJ, et al: Determining the effect that consultation-liaison psychiatry in primary care has on family physicians' psychiatric knowledge and practice. Psychosomatics 38:217-229, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Nickels MW, McIntyre JS: A model for psychiatric services in primary care settings. Psychiatric Services 47:522-526, 1996Link, Google Scholar

36. Williams P, Balestrieri M: Psychiatric clinics in general practice: do they reduce admissions? British Journal of Psychiatry 154:67-71, 1989Google Scholar

37. Tiemens BG, Ormel J, Simon GE: Occurrence, recognition, and outcome of psychological disorders in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:636-644, 1996Link, Google Scholar