Comparative Outcomes and Costs of Inpatient Care and Supportive Housing for Substance-Dependent Veterans

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the differential effectiveness and costs of three weeks of treatment for patients with moderately severe substance dependence assigned to inpatient treatment or to a supportive housing setting. Supportive housing is temporary housing that allows a patient to participate in an intensive hospital-based treatment program. Type and intensity of treatment were generally equivalent for the two groups. METHODS: Patients were consecutive voluntary admissions to the substance abuse treatment program of a large metropolitan Veterans Affairs medical center. Patients with serious medical conditions or highly unstable psychiatric disorders were excluded. Patients in supportive housing attended the inpatient program on weekdays from 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. They were assessed at baseline and at two-month follow-up. RESULTS: Baseline analyses of clinical, personality, and demographic characteristics revealed no substantive differences between the 62 patients assigned to inpatient treatment and the 36 assigned to supportive housing. The degree of treatment involvement and dropout rates did not differ between groups. Of the 55 inpatients completing treatment, 29 were known to be abstinent at follow-up, and of the 35 supportive housing patients completing treatment, 22 were abstinent. The proportion was similar for both groups, about 70 percent. The cost of a successful treatment for the inpatient group was $9,524. For the supportive housing group, it was $4,291. CONCLUSIONS: Given the absence of differential treatment effects between inpatient and supportive housing settings, the use of supportive housing alternatives appears to provide an opportunity for substantial cost savings for VA patients with substance dependence disorders.

Consistent with reviews suggesting that the treatment setting, such as inpatient, outpatient, or day hospital, has minimal impact on outcomes of treatment for substance dependence (1), current practice guidelines for the treatment of substance use disorders emphasize that treatment should be provided in the least restrictive setting possible (2). Considerations in the guidelines for selecting the appropriate setting include complicated withdrawal, acute and unstable medical conditions, history of treatment failure, presence of a comorbid psychiatric disorder, and evidence of dangerous behavior.

However, Finney and associates (3) have questioned the prevailing opinion on the effects of setting. They found that seven of 14 alcohol treatment studies revealed effects of the setting on at least one outcome variable, with five studies favoring inpatient over outpatient treatment. These authors made several recommendations about future comparative studies of effects of setting, two of which they discussed at length.

The first described the need for nonexperimental designs to address the problem of patient preselection—that is, the study of treatment effects only for individuals willing to accept randomized treatment assignment. The second was the need to explore options for settings within the general categories of inpatient and outpatient treatment. Examining outcomes of specific setting options is particularly important because significant numbers of substance abusers are homeless, which prevents their being treated in less expensive settings, such as outpatient facilities, that require participants to have a residence in the community. In addition, many substance abusers have comorbid disorders, which complicate treatment and often require inpatient care.

In this paper, we report the findings of a natural evaluation of the effectiveness and costs of rehabilitation for substance-dependent patients living in inpatient or supportive housing settings. Patients' characteristics strongly suggested a need for inpatient treatment under current treatment guidelines. These characteristics were previous treatment failure, high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, residential instability, unemployment, and use of multiple drugs. Supportive housing is temporary residential housing that allows a patient to participate in an intensive hospital-based treatment program.

The study used data obtained during the conversion of our long-standing inpatient treatment program to an outpatient program. During the transition, residential housing was provided to accommodate the demand for treatment, which presented an opportunity to examine the effects of setting. Although the study was conducted in a natural treatment setting and used only clinical data, the availability of both residential and inpatient resources allowed fairly stringent control of experimental parameters, including assignment of patients to treatment groups. All data were extracted from the clinical database maintained on all patients.

Methods

Subject selection

Subjects were consecutive voluntary admissions to the substance abuse treatment program of a metropolitan Veterans Affairs hospital for a period of six months, from July 1, 1996, to December 31, 1996. Patients were evaluated and admitted to the program in the order in which they applied for treatment. All patients met criteria for alcohol or drug dependence as defined by DSM-IV and had been rejected as candidates for outpatient treatment for one or more reasons—previous treatment failure, presence of symptoms suggesting a comorbid psychiatric disorder, use of multiple drugs, or homelessness.

For patients admitted to treatment, three exclusion criteria were applied to determine study eligibility: a serious medical disorder or a highly unstable psychiatric disorder, such as complicated withdrawal, a cardiovascular disorder, hallucinations, or suicide threats; ambulation problems requiring an inpatient setting; and female gender. Women were excluded from the study because supportive housing for them was unavailable. Patients excluded from the study were admitted directly to the inpatient treatment program.

Treatment conditions

Inpatient treatment.

The inpatient treatment program was an intensive three-week program with weekday activities from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. that included lectures, educational presentations, group therapy, individual counseling, 12-step assignments, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotic Anonymous (NA) meetings, family therapy, occupational therapy, and recreational activities. On weekends, patients completed assignments, attended AA or NA meetings, met with family and friends on hospital grounds, and received passes for short periods to meet with family or attend church services. Treatment plans were individualized and guided by a substance abuse counselor under the supervision of the treating psychiatrist.

Supportive housing.

Patients in the supportive housing program lived in apartments operated by a nonprofit agency and provided to the hospital on a contract basis. The apartment building was supervised by the agency staff 24 hours a day. On weekdays, supportive housing patients walked four blocks to the hospital by 7:30 a.m. and participated in the same therapeutic activities as did patients in the inpatient program until 5 p.m. In the evenings, these patients attended AA or NA meetings, housekeeping meetings, and group meetings at the residence.

On weekends, supportive housing patients worked on assignments and attended AA or NA meetings, but were otherwise free to use their time as they wished. These patients also had individualized treatment plans and received the same forms of treatment, under the same method of guidance and review, as did patients in the inpatient treatment program.

Assignment to treatment conditions.

We used a pseudorandom method of assignment based on the disparity in number of beds in the two conditions and the high demand for services. The inpatient program had 25 beds, and the supportive housing program had six beds. Study participants were accepted into treatment in the order of the date on which their admission evaluation was completed. Assignment was automatically made to the supportive housing condition if a bed was available. Otherwise patients were assigned to the inpatient condition. Patients ineligible for the study were always treated in the inpatient program. Although the assignment procedure was not random, it was dictated exclusively by conditions external to the control of the investigators.

Treatment program staff were not blind to the treatment conditions of the study. Patients were assigned to treatment staff based on a rotation system designed to equalize caseloads. This system was applied to all patients treated in the program, regardless of whether they were study participants.

Measures

Baseline measures.

Sociodemographic data were obtained for all patients. They completed a medical and substance abuse history and an axis I diagnostic interview. All patients were given a physical examination that included laboratory tests and x-rays. They also completed the Neuropsychological Screening Test (NST) (Vanderploeg R, Schinka J, unpublished, 1994) and the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) (4).

The NST is a neurocognitive screening test with known psychometric characteristics (5,6,7,8). Possible scores range from 0 to 289, with higher scores indicating better cognitive functioning. The PAI is a self-report psychopathology inventory that has been found to be a reliable and valid measure in the evaluation of substance abusers (9,10), Possible scores range from 30 to 115, with higher scores indicating greater psychopathology.

In-treatment measures.

Two measures were used to examine the degree of patients' treatment participation. The first was a count of patients who left treatment or who were terminated from treatment because of violations of program regulations. The second was the Treatment Involvement Rating Scale (TIRS) (11), a 15-item observer rating scale that provides a measure of involvement in treatment by querying behaviors such as participation in group therapy, affiliation with other patients, and commitment to abstinence. The TIRS has been shown to be reliable, unrelated to demographic and treatment variables, and independent of personality characteristics (11). Patients' counselors completed the TIRS on the day of discharge.

Follow-up measures.

At a scheduled 60-day follow-up appointment, patients underwent breath analysis and urine testing. They completed a brief structured follow-up interview with a research assistant who was blind to the treatment condition. If a patient failed to keep the follow-up appointment, the research assistant attempted to complete the interview by phone. For patients residing in structured settings in the community, such as halfway houses, who could not be contacted directly, interviews were conducted with staff counselors in adherence with a standard consent protocol.

Cost assessments.

The primary costs of substance abuse treatment are associated with personnel. We included in our personnel cost estimates all individuals who provided full- or part-time services, including professionals such as psychiatrists, nurses, and occupational therapists and support staff. The estimates included the cost of benefits and the differential pay between shifts. These costs were then proportionately allocated to each program (supportive housing and inpatient) based on the number of participating patients in each program for each shift.

Housing costs for inpatients were extracted from data provided by the VA national cost distribution report, which uses standardized accounting procedures to distribute both direct and indirect costs to each health care program at each VA facility. The housing cost estimate included costs related to bed occupancy, meals, and building management, maintenance, and utilities. The cost of treatment space (for example, group rooms) and staff offices were included. Patients in the supportive housing program received housing and meals—two each weekday and three each weekend day—at a fixed contract rate. Thus this element of housing costs reflected actual, rather than estimated, costs.

For subjects in supportive housing, we also included the costs of the five meals each week (lunch) that were provided by the medical center, and we added an estimate of the cost of treatment and staff office space. The estimate was based on calculations of the costs of operating the same treatment program in an equivalent facility in the community (annual rental, insurance, utilities, and maintenance).

Several small costs that would be expected to be equal for subjects in both treatment groups were not examined. They included costs for items such as chest x-rays and routine intake laboratory tests. Because most patients entering the treatment program had no substantive wage income in the previous months, lost wages were not examined in the cost estimates.

Results

Statistical analyses and sample size

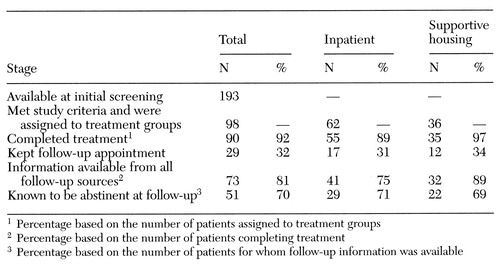

Group comparisons for categorical variables were conducted using chi square tests and Fisher's exact test; for continuous variables t tests and multivariate analyses of variance were used. In comparing groups on multiple baseline and in-treatment measures to determine if they were equivalent at successive stages of analysis, we set the significance level at .05 and did not adjust for the total number of analyses, which provided sensitive tests of group differences. However, because of the importance of finding differences between groups in outcome measures, we set the significance level at .10. Power analyses, as recommended by Cohen (12), revealed that the sample size was sufficient to provide power in the range of .67 to .80 or higher, depending on the N for any specific analysis. To facilitate the description of treatment comparisons, Table 1 shows the number of patients available at each stage of the study.

Sample characteristics

Of the 193 patients entering the treatment program during the six-month study period, 98 (54 percent) met study criteria for eligibility. The majority of ineligible patients had unstable psychiatric conditions (N=36) such as hallucinations or medical conditions (N=32) such as cardiac disorders. Comparison of the 98 eligible and 95 ineligible patients revealed no differences in employment status on admission, marital status, homelessness, ethnic group, history of previous treatment, years of education, overall psychopathology (mean of all PAI clinical scales), and involvement in treatment (TIRS total score).

However, ineligible patients were slightly older than eligible patients (mean±SD=47.2±10.6 years versus 43.8±8.20; t=2.50, df=1, p<.05). The ineligible patients also had lower NST scores (85.6±21.7 versus 97.2±18.1; t=4.10, df=19, p<.001) and were more likely to have a co-existing axis I psychiatric disorder (55 percent versus 32 percent; (χ2=10.50, df=1, p<.005). The findings for NST scores and the frequency of axis I psychiatric disorders are not surprising, given that patients with highly unstable psychiatric conditions were excluded from the study.

Sixty-two patients were assigned to inpatient treatment and 36 to supportive housing. Because approximately half of the 25 inpatient beds were filled by patients ineligible for the study, the ratio of patients to available beds was approximately the same for the two groups—62 patients per 12 beds for the inpatient group and 36 patients per six beds for the supportive housing group.

The inpatient and supportive housing groups were compared on all baseline and in-treatment variables. No differences were found between groups on any variable except the mean PAI score. Inpatients had a lower mean score than patients in supportive housing (mean±SD= 64.4± .7 versus 71.4±9.6; t=3.20, df=1, p<.01). Subsequent analyses revealed that this result was due to higher scores for mania among the supportive housing patients. However, despite this difference, scores for both groups were within the range interpreted as being clinically unremarkable (4).

Group differences

Eight patients were lost to the study due to voluntary termination or disciplinary discharge. No difference between groups was found in the proportion of patients lost or in the TIRS total score. Of the 90 subjects who completed treatment, 29 (32 percent) kept their follow-up appointment. The proportion of subjects who kept their appointment did not differ by treatment group. Examination of baseline variables revealed no differences between patients who kept their follow-up appointment and those who did not.

Examination of follow-up data for patients who kept their follow-up appointment revealed that only four of the inpatients had used alcohol or drugs during the follow-up period. Because three of these subjects had used alcohol or drugs on more than one occasion, we defined any use of drugs or alcohol as constituting relapse. Three of these patients failed breath analysis tests or urine drug screens at the time of their appointment. No patient who denied use of alcohol or drugs failed the breath analysis test or the urine drug screen. Although all patients who relapsed were in the inpatient group, the chi square test for differences in relapse rates between the two groups was not significant.

Outcome data from all sources—follow-up appointments, telephone interviews with patients, and interviews with staff in halfway houses—were available for 73 subjects (81 percent). Comparisons of the two treatment groups on baseline variables revealed no differences, with the exception of the difference in the mean PAI score discussed above. Of the 73 subjects with outcome data, 51 (70 percent) were abstinent at 60 days posttreatment. The proportion of subjects who had relapsed by 60 days posttreatment did not differ by treatment group.

Cost analyses

The weekly per-patient cost for patients in inpatient treatment was $1,674 ($719 for personnel costs and $955 for housing costs). For the supportive housing patients, the weekly cost was $899 ($624 for personnel costs and $275 for housing costs).

To estimate the cost of a successful treatment, we distributed the total costs of treatment for all patients completing treatment to patients who were found to be abstinent at the 60-day follow-up. Of the 55 inpatients who completed treatment, 29 were known to be abstinent. The average cost of a successful treatment for the inpatient group was $9,524. Of the 35 supportive housing patients who completed treatment, 22 were known to be abstinent at two months. The average cost of a successful treatment for the supportive housing group was $4,291. These estimates reflect upper boundaries of the cost of successful treatment because they do not include a count of subjects who may have been abstinent at follow-up but for whom no follow-up information could be obtained.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study we took advantage of changes in a substance abuse treatment program to examine the differential outcome and cost of hospital-based treatment for patients in an inpatient unit and those in a supportive housing setting. The sample appeared to be representative of those treated in VA settings in metropolitan areas. The sample was characterized by high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, residential instability, unemployment, use of illegal drugs, and previous treatment failure. All patients received three weeks of active treatment and were followed up two months after discharge.

The results of this study are relatively straightforward. Regardless of whether outcome was measured by a personal interview supported by drug screening or by less rigorous methods of obtaining follow-up data, the study found no difference in short-term outcome between patients treated in a traditional inpatient setting and those treated in a supportive housing setting. Furthermore, the percentage of patients abstinent at follow-up—approximately 70 percent of those for whom follow-up information was available—compares favorably with short-term results from other studies, given the severity of the substance dependence problems of our sample. For example, Walsh and colleagues (13) examined outcomes of patients in "mixed" treatment—approximately half inpatient and half outpatient. At three-month follow-up they found that approximately 70 percent of patients for whom information was available were abstinent.

It is notable that almost half (46 percent) of the patients considered for this study were excluded by the study criteria. Most were excluded because of unstable medical or psychiatric conditions that mandated inpatient admission. However, a large proportion of the patients who were included in the study had characteristics suggesting treatment in more restrictive settings. Thus we believe that the results of this study should be seen as generalizing to the moderately severe end of the spectrum of substance dependence. For the type of patient excluded from our study, future research should examine alternative treatment strategies, such as short-term stabilization followed by supportive housing, as a means of delivering effective and less expensive substance abuse treatment.

Not surprisingly, cost estimates for patients in the supportive housing treatment condition were substantially less than for those in the inpatient condition. This study was not immune to some of the shortcomings of research in natural settings. One concern was the effectiveness of the pseudorandom method of treatment assignment. However, analyses of patient characteristics at sequential stages of the study revealed no differences between treatment groups. Thus the method of assignment appeared to be effective in preventing bias, at least on the basis of the measured demographic, psychological, and treatment-involvement variables.

A threat to the validity of the study is that treatment staff were not blind to the patient's treatment condition during active treatment. However, two sources of evidence argue against the hypothesis that patients in the two conditions were treated differently. The first is that statistically equal proportions of the two patient groups completed treatment and kept follow-up appointments. Admittedly, treatment completion is a global indicator of treatment equivalence and does not address issues such as equal frequencies of counselor contact or the quality of the patient-counselor relationship. A second source of evidence is that TIRS scores were not found to differ between the groups at any stage of the study, suggesting that factors underlying treatment motivation and participation had no differential effect on the two groups.

The results obviously cannot be extended to the follow-up intervals recommended for outcome studies of this type (14). Because the study used existing resources to collect data during a transition in the treatment program, the resources required for long-term follow-up were not available. However, we believe that the results are still noteworthy because it has long been known that two-thirds of the risk for relapse in the first year following treatment occurs in the first three posttreatment months (15,16). Thus results limited to this critical short time frame should still be informative.

One important aspect of this study is that treatment intensity—the number and type of treatment experiences—for patients within each of the settings was largely equivalent, differing only in evening and weekend activities. Treatment intensity has been found to be associated with better outcomes (17,18). Thus the primary conclusion to be drawn from this study is that appreciable treatment cost savings can be achieved without sacrificing the key components of treatment success.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

When this work was done, all the authors were affiliated with the James A. Haley Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Tampa, Florida. Dr. Schinka is a clinical psychologist, Dr. Francis is chief of ambulatory psychiatric services, Dr. Hughes is chief of alcohol and drug abuse treatment, Mr. LaLone is a research associate, and Dr. Flynn was formerly chief of psychiatry. Dr. Flynn is now chief of psychiatry at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in Houston. The authors are also affiliated with the University of South Florida in Tampa. Dr. Schinka is associate professor, Dr. Francis is assistant professor, and Dr. Hughes is professor in the department of psychiatry, and Mr. LaLone is with the department of psychology. Send correspondence to Dr. Schinka at the Haley VA Medical Center, Psychology Service (116B), 13000 Bruce B. Downs Boulevard, Tampa, Florida 33612 (e-mail, [email protected]). An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association held August 5-16, 1997, in Chicago.

|

Table 1. Subjects available at stages of treatment in a study of veterans assigned to treatment in an inpatient setting and a supportive housing setting

1. McGrady B, Langenbucher J: Alcohol treatment and health care system reform. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:737-746,Google Scholar

2. Mirin S, Batki S, Bukstein O, et al: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Substance Use Disorders: Alcohol, Cocaine, Opioids. American Journal of Psychiatry 152(Nov suppl):1-80, 1995Google Scholar

3. Finney J, Hahn A, Moos R: The effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment for alcohol abuse: the need to focus on mediators and moderators of setting effects. Addiction 91:1773-1796, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Morey L: Personality Assessment Inventory. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1991Google Scholar

5. Retzlaff P, Vanderploeg R, Schinka J, et al: Feigned malingering and NST performance. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Aug 9-13, 1996Google Scholar

6. Schinka J, Vanderploeg, R: Validity of the NST in a drug-dependent sample. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, New York, Aug 11-15, 1995Google Scholar

7. Schinka J, Vanderploeg R, Retzlaff P, et al: NST and CVLT performance: a validity study. Presented at the annual meeting of the National Academy of Neuropsychology, Orlando, Fla, Nov 2-6, 1994Google Scholar

8. Vanderploeg R, Schinka J: The Neuropsychological Screening Test (NST): an initial validity study with an elderly population. Presented at the annual meeting of the National Academy of Neuropsychology, Orlando, Fla, Nov 2-6, 1994Google Scholar

9. Schinka J: PAI scale characteristics and factor structure in the assessment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Personality Assessment 64:101-111, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Schinka J: PAI profiles in alcohol-dependent patients. Journal of Personality Assessment 65:35-51, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Schinka J, Lucking R, Francis E: Development of a treatment involvement scale for substance abusers. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Aug 13-17, 1993Google Scholar

12. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

13. Walsh D, Wingson R, Merrigan S, et al: A randomized trial of treatment options for alcohol-abusing workers. New England Journal of Medicine 325:775-782, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Nathan P, Skinstad A: Outcomes of treatment for alcohol problems: current methods, problems, and results. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 55:332-340, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hunt W, Barnett L, Branch L: Relapse curves for individuals treated for heroin, smoking, and alcohol addiction. Journal of Clinical Psychology 27:455-456, 1971Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Marlatt G, Gordon J: Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York, Guilford, 1985Google Scholar

17. Feuerelein W, Kufner H: Prospective multicentre study of in-patient treatment for alcoholics:18- and 48-month follow-up. European Archives of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 239:144-157, 1989Google Scholar

18. Monahan S, Finney J: Explaining abstinence rates following treatment for alcohol abuse: a quantitative synthesis of patient, research design, and treatment effects. Addiction 91:787-805, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar