Relationship of Cocaine and Other Substance Dependence to Well-Being of High-Risk Psychiatric Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The co-occurrence of substance dependence disorders was determined in a sample of 160 frequently hospitalized adults with severe mental illness, and the relationship between substance dependence and psychosocial functioning and well-being was examined. METHODS: A structured interview was used to assess subjects for co-occurring current DSM-III-R substance dependence disorders during an acute psychiatric hospitalization. They were administered a structed interview that included the subscales of the Addiction Severity Index, the Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale, Lehman's Quality of Life Interview, Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale, the Mastery Scale, and questions about service needs. RESULTS: Seventy-eight of the subjects (48.8 percent) were diagnosed as having at least one current substance dependence disorder. Most subjects with comorbid substance dependence were polysubstance dependent (55.1 percent), and almost half (44.9 percent) met criteria for cocaine dependence. Subjects who were substance dependent were significantly overrepresented among those diagnosed with bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, and major depression. When the analysis controlled for demographic characteristics and primary diagnosis, comorbidity was related to depressive symptoms, adverse life conditions, and diminished life satisfaction in several domains. Substance-dependent subjects were significantly more likely to have been arrested and jailed than nondependent subjects. Cocaine-dependent subjects were significantly less satisfied than all other subjects with their living situation and personal safety and more likely to request assistance for their drug and alcohol use problems. CONCLUSIONS: The findings corroborate high rates of co-occurring substance dependence disorders among frequently hospitalized patients with severe mental illness. They also reveal a high prevalence of cocaine dependence and a dramatic pattern of negative correlates of cocaine dependence. The findings suggest that successful interventions for substance dependence may improve these patients' life circumstances and that psychiatric patients may be particularly receptive to such interventions during hospitalization.

Substance use disorders are widespread among psychiatric patients. The Epidemiological Catchment Area study estimated a 29 percent rate of lifetime substance use disorders among persons meeting criteria for a lifetime mental disorder. Rates of co-occurring substance dependence disorders among individuals with lifetime diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression have been estimated at 47 percent, 56 percent, and 27 percent, respectively (1).

A literature review estimated that between 20 and 40 percent of persons with schizophrenia have co-occurring current substance dependence disorders (2), and a review of studies conducted from 1960 to 1991 concluded that rates of alcohol and stimulant abuse among adults with severe and persistent mental illness may be increasing (3). Several recent studies have indicated that cocaine abuse has become increasingly common among psychiatric patients (4,5).

Substance use disorders often exacerbate adverse life conditions for psychiatric patients. Compared with psychiatric patients who do not have substance use disorders, those with comorbid disorders may experience more depression (6,7); be less likely to obtain aftercare services (8); have higher rates of rehospitalization, incarceration, and medication noncompliance (7); and be at greater risk for suicide and violence (9,10,11).

A burgeoning literature points to research needed to fill gaps in our knowledge. For example, studies generally have not assessed the full range of substance dependence disorders in samples representing the full range of severe mental disorders. Comprehensive research diagnostic assessments that make formal distinctions between abuse and dependence and current and lifetime disorders have been infrequently used. Standardized instruments with known psychometric properties have been infrequently used to obtain data on drug use patterns and well-being. Few studies have compared adults with severe mental illness who meet dependence criteria for different substances and those who do not.

This study examined substance dependence disorders co-occurring with severe and persistent mental disorders in a sample of frequently hospitalized psychiatric patients. Relationships between comorbidity and patients' characteristics, alcohol and drug use patterns, psychosocial functioning, perceptions of well-being, and negative life events were investigated, with a focus on specific drug dependence disorders and their correlates.

Methods

Subjects

The sample consisted of 160 consecutively admitted, frequently hospitalized adults with severe and persistent mental illness recruited during an acute psychiatric hospitalization at San Francisco General Hospital, a county general hospital and teaching service of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) (12). Patients included in the study had at least one psychiatric hospitalization during the 12 months before the index hospitalization, were between the ages of 18 and 59, were not participating in intensive community-based services, were discharged to a community location in the San Francisco metropolitan area, and were sufficiently coherent to complete the interview. Study procedures were approved by the UCSF committee on human research.

Procedures

Subjects provided written informed consent. To determine substance dependence status, subjects completed a computerized version of the drug and alcohol use sections of the Quick DIS III-R (QDIS3R) (13), which maps onto the Diagnostic Interview Schedule III-R. (The version mapping onto DSM-IV had not been released at the time of the study.) Use of all drugs included in the DSM-III-R , except nicotine and caffeine, was assessed. Subjects completed a structured intake interview following the QDIS3R. Interviews were administered between 1994 and 1996 by trained master's-level research associates.

Measures

Subjects were classified as having a comorbid disorder if they had a current substance dependence disorder; these subjects met lifetime diagnostic criteria for a substance dependence disorder and had at least one symptom of dependence in the past 12 months based on QDIS3R results. The 78 subjects found to have comorbid substance dependence disorders were divided into three subgroups. In the first group were 35 subjects dependent on cocaine, some of whom were dependent on additional substances. In the second group were 15 subjects dependent on alcohol and not dependent on any other substance. In the third group were 28 subjects dependent on one or more substances but not on cocaine. Creation of these groups isolated cocaine-dependent and "pure" alcohol-dependent subjects from all other subjects.

Each subject's primary DSM-IV diagnosis for the target episode was determined by the attending psychiatrist at hospital discharge and was obtained from the hospital chart. Secondary diagnoses were not included in data collection because not all subjects received a secondary diagnosis, and many had deferred secondary diagnoses.

The intake interview included several instruments. The drug and alcohol sections of the fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (14) were administered. We generated a dichotomous variable (use versus nonuse) for each drug category in the ASI from subjects' reported frequency of drug and alcohol use in the 30 days before hospitalization. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D) (15), the Self-Esteem Scale (16), and the Mastery Scale (17) were integrated into the interview. The CES-D assesses depressive symptoms. Subjects report the frequency of experiencing each of 20 symptoms, with item scores ranging from 0, rarely, to 3, almost all of the time. Possible scores range from 0 to 60. The coefficient alpha reliability estimate for our sample was .90 for this scale.

The ten-item Self-Esteem Scale measures self-worth and self-acceptance. Possible scores range from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem. Reliability for our sample was estimated at .73. The Mastery Scale is a seven-item instrument that addresses whether subjects regard events in their lives as being under their control (self-efficacy). Each item is rated on a 4-point scale, from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Scores range from 7 to 28, with higher scores reflecting more self-efficacy. Reliability for our sample was estimated at .68.

Well-being was measured during the intake interview using Lehman's Quality of Life Interview (QOLI) (18), developed for this population. Satisfaction with living situation, finances, work, safety, daily activities, health (modified for our sample), and social relations were assessed. Satisfaction is rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1, terrible, to 7, delighted. In our sample, internal consistency of scales ranged from .76 to .81. Well-being was also assessed by asking subjects whether and how many times they had been homeless, arrested, jailed, and victimized in the previous six months. These variables were dichotomized (for example, homeless versus not homeless) for purposes of statistical analyses.

Finally, life circumstances for which subjects desired assistance were surveyed using ten face-valid items we developed. Responses were dichotomized as desiring some assistance and desiring no assistance.

Data analysis

Differences between subjects who were substance dependent and those who were not were assessed using t tests and chi square tests of association. Hierarchical multivariate regression or multivariate logistic regression, based on the dependent variable—continuous or categorical, respectively—were used in complex model testing that investigated differences among the three groups of subjects with comorbid substance dependence and those without comorbid dependence. Based on theoretical importance and first-order associations in the data, all models controlled for effects of age, gender, education, race, and primary diagnosis. To facilitate interpretation, age was dichotomized at less than 40 years or 40 years and older. Education was dichotomized as completion of high school (or general equivalency diploma) or noncompletion, and race was dichotomized as African American or not.

Odds ratios were calculated in conjunction with significant results of logistic regressions. They indicate the likelihood of one group of subjects having the characteristic compared with all other subjects after the effects of the covariates were controlled. Analyses were conducted using SAS-PC, version 6.11.

Results

Most of the 160 subjects were male (97 subjects, or 60.6 percent), unemployed (135 subjects, or 84.4 percent), and not married (150 subjects, or 93.8 percent). More than two-thirds of subjects reported that they completed high school or a general equivalency diploma (105 subjects, or 65.6 percent). The sample was racially and ethnically diverse, consisting of 63 European Americans (39.4 percent), 33 African Americans (20.6 percent), 28 Latinos (17.5 percent), 18 Asian-Pacific Islanders (11.2 percent), nine Native Americans (5.6 percent), and nine others (5.6 percent). Subjects' mean±SD age was 36.96±9.83 years, and their mean age at first psychiatric hospitalization was 23.64±9.70 years.

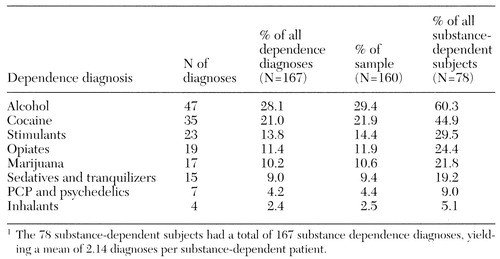

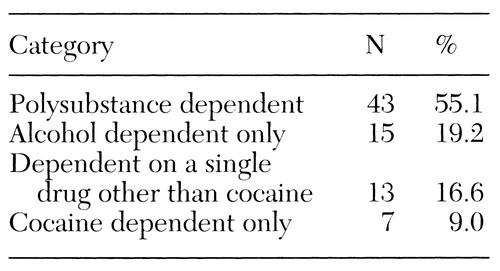

Based on the QDIS3R, almost half of the subjects (78 subjects, or 48.8 percent) were assessed to have at least one current substance dependence disorder, and 43 of these subjects (55.1 percent) were dependent on more than one drug. Table 1 indicates the frequency of drug dependence diagnoses. Table 2 shows the distribution of diagnoses among subjects with comorbid disorders. Polysubstance-dependent subjects had a mean of three dependence diagnoses and a median of two.

The most prevalent primary diagnoses at discharge from the target episode were schizophrenia (55 subjects, or 34.4 percent) and bipolar disorder (52 subjects, or 32.5 percent), followed by psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (21 subjects, or 13.1 percent) and major depression (18 subjects, or 11.2 percent). Fourteen subjects (8.8 percent) had other diagnoses—eight had adjustment disorders (three with depressed mood and three with mood-conduct disorder), two subjects had an affective disorder attributed to HIV disease, two had drug-induced disorders, one had posttraumatic stress syndrome, and one had obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. All subjects had been diagnosed as having a major mental disorder in treatment episodes before or after the target episode.

A significant overall association was found between substance dependence status and discharge diagnosis (χ2 =13.42, df=4, p<.01). Tests by diagnostic group indicated that substance-dependent subjects were overrepresented among subjects with bipolar disorder (χ2 =6.16, df=1, p<.02), psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (χ2 =4.97, df=1, p<.03), and major depression (χ2 =4.47, df=1, p<.05).

Comparisons of subjects with and without comorbidity

Sociodemographic characteristics.

The mean age of subjects who were substance dependent was not significantly different from that of the subjects who were not substance dependent. Mean±SD ages ranged from 34.81±10.62 years, for subjects who were dependent on substances other than cocaine, to 41.20±8.62 years, for subjects dependent only on alcohol. The mean±SD age at first psychiatric hospitalization was 22.33±8.31 years for subjects with comorbid dependence and 24.88±10.78 years for those with no comorbidity, which was also not a significant difference.

No difference was found between groups in gender, marital status, and employment status. However, significant relationships were found between substance dependence and educational status (χ2 =8.51, df=3, p<.05) and race-ethnicity (χ2 =18.22, df=9, p<.05). These results indicate that subjects who were not substance dependent were overrepresented in the group that had completed high school, and that African-American subjects were overrepresented in the cocaine-dependent group and underrepresented in the group that was not substance dependent.

Drug and alcohol use.

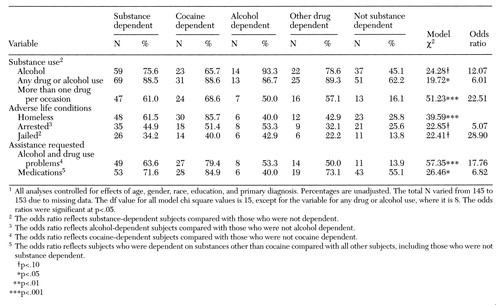

Multivariate logistic regression analyses controlling for effects of covariates were conducted for each drug use indicator. Of the 14 indicators of substance use in the previous 30 days, three had a significant relationship with comorbid status—alcohol use, any substance use, and polysubstance use (use of more than one substance on a single occasion). As the odds ratios in Table 3 show, compared with subjects who were not substance dependent, those who were substance dependent were 12 times more likely to report drinking alcohol, six times more likely to report using any substance, and almost 23 times more likely to report polydrug use. All of the odds ratios are significant at the .05 level. However, due to wide 95 percent confidence intervals for the odds ratios, the values are most conservatively interpreted as indicating a significant difference in the likelihood of having the attribute rather than as reflecting literal degrees of likelihood. This interpretation should apply to all the odds ratios reported.

Clinical status.

The analyses of the relationships between comorbidity and depression, self-esteem, and self-efficacy indicated that scores on the CES-D were related to comorbid status (partial F=11.25, df=9,129, p<.001; beta for comorbidity=6.62) after controlling for the covariates. Substance-dependent subjects had significantly higher scores, indicating more depressive symptoms, than subjects who were not dependent (mean ±SD scores=34.10±13.80 and 23.84± 12.88). No relationship was found between comorbidity and self-esteem and self-efficacy.

Adverse life circumstances.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses completed to test for the association of comorbidity and homelessness, arrests, being jailed, and being a victim of violent or nonviolent crime in the past six months indicated a significant relationship to the first three variables, after controlling for covariates. As Table 3 shows, for homelessness the overall model was significant. The association between homelessness and cocaine dependence approached significance (p<.06). However, the odds ratio for cocaine dependence was not significant. The logistic regression analysis for being arrested indicated that alcohol-dependent subjects were five times more likely to report having been arrested than all other subjects.

The logistic regression for having been jailed indicated that substance-dependent subjects were almost 29 times more likely to report having been jailed than nondependent subjects. However, within the group of substance-dependent subjects, those who were dependent on drugs other than cocaine were only 14 percent as likely to report spending time in jail (data not shown).

Service needs.

Help with alcohol and drug problems and help with medications were the only service requests associated with comorbidity. Two of the multivariate logistic regression analyses showed significant effect. As shown by the odds ratios in Table 3, cocaine-dependent subjects were almost 18 times more likely than all other subjects to request help with alcohol and drug use problems. They also were 13 times more likely to request assistance with medications. Subjects dependent on substances other than cocaine were almost seven times more likely than all other subjects to request assistance with medications.

Life satisfaction.

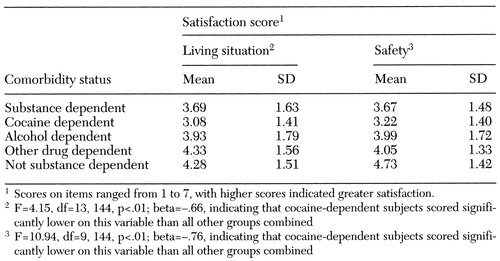

Satisfaction scores on two life domains had significant associations with cocaine dependence. As Table 4 shows, cocaine-dependent subjects had significantly lower satisfaction ratings for living situation and personal safety than all other subjects. For living situation, cocaine-dependent subjects' mean rating was 3.08±1.41, whereas for all other subjects it was 4.25±1.55. For personal safety, cocaine-dependent subjects' mean rating was 3.22±1.40 versus a mean of 4.49±1.47 for all other subjects.

Discussion

The rate of comorbidity in this sample (48.8 percent) corroborates results of other studies of co-occurring substance dependence among frequently hospitalized adults with severe and persistent mental illness (1,2,3,4,5). Moreover, our data show that among subjects with comorbid substance dependence, dependence on more than one substance was the norm (55.1 percent), and simultaneous use of multiple drugs on any single occasion was widespread (60.5 percent) during the previous 30 days.

In this study, comorbid major mental and substance dependence disorders were associated with negative life circumstances and dissatisfaction. Substance-dependent subjects were more likely than nondependent subjects to experience being arrested and jailed. Substance-dependent subjects reported less satisfaction with their living situation and safety than nondependent subjects. In addition, it is notable that cocaine-dependent subjects reported the least satisfaction with living situation and safety of all subjects and were the most likely to request assistance with alcohol and drug problems.

The results of this descriptive study suggest several research directions. Our findings of a pattern of negative correlates of comorbidity, and especially of cocaine dependence, warrant replication. If confirmed, further studies should be designed to address the association of comorbid substance dependence disorders in general, and of comorbid cocaine dependence in particular, with increased life adversity and decreased life satisfaction.

The biochemical properties of cocaine and other drugs may wreak particular havoc on the brain chemistry of patients with major mental disorders, whose brain chemistry may already be impaired. The stimulant properties of cocaine may be particularly attractive to certain subgroups of persons with severe mental illness who are already predisposed for negative consequences. More knowledge about these issues should contribute to the design of interventions for patients with co-occurring severe mental disorders and substance dependence disorders.

The findings have important implications for mental health services providers. The correlates of comorbidity suggest that successful interventions for substance dependence in the severely mentally ill population may improve their life circumstances. Other data gathered in this study, such as subjects' requests for assistance and for certain services including alcohol and drug treatment, suggest that frequently hospitalized patients with severe mental illness may be particularly receptive to interventions during hospitalization. It is noteworthy that cocaine-dependent subjects, who generally reported the most severe circumstances, were also the most likely to express a desire for services. Given other research indicating that severely mentally ill patients with comorbid substance use disorders are less likely to receive aftercare and are more likely to be rehospitalized than those without substance use problems (2,3), a psychiatric hospitalization may be an opportune time to initiate substance abuse treatment.

Several studies have suggested promising inpatient strategies for providing treatments to adults with severe mental illness and co-occurring cocaine dependence. They include a cocaine treatment referral program for psychiatric patients initiated during a psychiatric hospitalization (4), a day treatment program for cocaine abusers within a psychiatric service of a general hospital (5), and a substance abuse consultation-liaison team that leads inpatient dual diagnosis groups and facilitates postdischarge linkages to outpatient substance abuse treatment (19). Other studies have suggested that when included in standard drug treatment programs, some psychiatrically impaired drug users can achieve outcomes comparable to those of drug users without psychiatric disorders (20,21).

It is apparent that severely mentally ill adults with comorbid substance use disorders need substance abuse interventions. Findings suggest that substantial benefits may be realized by initiation of treatment during an inpatient hospitalization, a period when patients' lives are regulated and their basic needs for shelter, food, safety, and medication are met.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant MH-50856 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and grant DA-10836 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Arns was an NIMH postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, San Francisco, when this work was initiated. The authors acknowledge the contributions to data collection of David Fariello, M.S.W., Aline Wommack, R.N., M.S., and Joanne Wile, M.S.W., and the contributions to data analysis of Sharon Boles, Ph.D., Jennifer Long, M.S., and Lori Quigley, Ph.D.

Dr. Havassy is adjunct professor in the department of psychiatry and director of the treatment outcome research group at the University of California, San Francisco, 74 New Montgomery Street, Suite 440, San Francisco, California 94105 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Arns is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at Harbor-University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center. Portions of this work were presented at the annual scientific meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence held June 10-15, 1995, in Scottsdale, Arizona, and at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association held October 29 to November 2, 1995, in San Diego.

|

Table 1. Prevalence of substance dependence diagnoses among 160 frequently hospitalized adults with severe mental illness1

|

Table 2. Categories of substance dependence for the 78 subjects with co-occurring dependence disorders

|

Table 3. Variables associated with substance dependence among 160 adults with severe mental illness, by comorbidity status1

|

Table 4. Mean satisfaction scores in two life domains among 160 adults with severe mental illness, by comorbidity status1

1. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 264:2511-2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Levinson DF, et al: Prevalence of substance abuse in schizophrenia: demographic and clinical correlates. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:31-56, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Cuffel BJ: Prevalence estimates of substance abuse in schizophrenia and their correlates. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:589-592, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Galanter M, Egelko S, De Leon G, et al: Crack/cocaine abusers in the general hospital. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:810-815, 1992Link, Google Scholar

5. Galanter M, Egelko S, De Leon G, et al: A general hospital day program combining peer-led and professional treatment of cocaine abusers. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:644-649, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Cuffel BJ, Heithoff KA, Lawson W: Correlates of patterns of substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:247-251, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Drake RE, Osher FC, Wallach MA: Alcohol use and abuse in schizophrenia: a prospective community study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:408-414, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Solomon P: Receipt of aftercare services by problem types: psychiatric, psychiatric/substance abuse, and substance abuse. Psychiatric Quarterly 58:180-188, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Barry KL, Fleming MF, Greenly JR, et al: Characteristics of persons with severe mental illness and substance abuse in rural areas. Psychiatric Services 47:88-90, 1996Link, Google Scholar

10. Mulvey EP: Assessing the evidence of a link between mental illness and violence. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:663-668, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Safer D: Substance abuse by young adult chronic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:511-514, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Havassy BE, Chafetz L, Miller JV, et al: Impact of alcohol and drug dependence on service needs of seriously mentally ill adults. Presentation at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, San Diego, Oct 29-Nov 2, 1995Google Scholar

13. Marcus S, Robins LN, Bucholz KK: Quick Diagnostic Interview Schedule III-R, Version 1.0. St Louis, Washington University, Department of Psychiatry, 1990-1991Google Scholar

14. McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:199-213, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385-401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Rosenberg M: Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1965Google Scholar

17. Pearlin LI, Lieberman M, Menaghan E, et al: The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22:337-356, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lehman AF: A Quality of Life Interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Greenfield SF, Weiss RD, Tohen M: Substance abuse and the chronically mentally ill: a description of dual diagnosis treatment services in a psychiatric hospital. Community Mental Health Journal 31:265-277, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Galanter M, Egelko S, Edwards H, et al: Can cocaine addicts with severe mental illness be treated along with singly diagnosed addicts? American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 22:497-507, 1996Google Scholar

21. Saxon AJ, Calsyn DA: Effects of psychiatric care for dual diagnosis patients treated in a drug dependence clinic. American Journal Drug and Alcohol Abuse 21:303-313, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar