Depression Screening Scores During Residential Drug Treatment and Risk of Drug Use After Discharge

Abstract

Depression is a highly prevalent disorder among patients in residential drug treatment, and the pragnosis for recovery from chemical dependency among depressed persons is uncertain. This report presents one-year follow-up data on alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana use among patients who completed the center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) during their inpatient stay in one of 12 residential treatment programs in the Midwest. At 12-month follow-up, CES-D scores in the depressed range were significantly associated with risk of relapse for alcohol and marijuana use, but not for cocaine use.

Patients in treatment for drug abuse often report feelings of depression (1). Unfortunately, the prognosis for recovery from chemical dependency among depressed persons remains unclear and may vary by severity of depression and drug preference (2,3,4,5).

During a randomized community intervention trial involving 575 patients in 12 residential drug treatment centers in Iowa, Kansas, and Nebraska, an opportunity arose to test hypotheses about the likelihood of relapse to use alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine among patients who met or did not meet screening criteria for depression while in treatment. This report presents data on associations between self-reported depression during treatment and postdischarge drug use over one year of follow-up. To our knowledge, similar longitudinal findings from a large sample of community-based treatment programs have not been reported previously.

Methods

The primary study was undertaken to test the safety and efficacy of encouraging smoking cessation early in alcohol treatment. The research protocol and primary findings have been detailed elsewhere (6). Briefly, a low-intensity smoking cessation intervention was provided in six residential treatment centers, while standard care alone was provided in six closely matched programs.

About 50 patients from each of the 12 centers were recruited for a one-year follow-up study. Eligible patients were adult daily smokers with a history of serious problems with alcohol who were willing to complete an enrollment questionnaire and a follow-up questionnaire at one, six, and 12 months after treatment discharge. A $10 incentive was offered for the return of each questionnaire. Collateral contact data were collected for a randomly selected subset of respondents (27 percent). Saliva cotinines were obtained from 70 percent of those who reported no longer smoking at follow-up.

Part of the self-administered enrollment battery was the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The CES-D is a 20-item questionnaire that has been shown to distinguish depressed from nondepressed alcoholics (7). The standard cutoff point is 16, with scores at or above that value suggesting current depression. Several studies have reported improved specificity and fewer false positives with use of higher cutoff points (8,9). Other components of the enrollment battery included the Self-Administered Alcoholism Screening Test (SAAST), the Timeline Followback Drinking Calendar, the Decisional Balance Scale for Smoking, and the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (6).

Drug use at follow-up was assessed with 15 dichotomous, Likert-scaled items previously validated in work with similar populations. For example, participants reported alcohol use between their date of discharge and six-month follow-up by indicating whether or not they had "even one alcoholic drink," "more than one alcoholic drink," or "several drinks on one occasion" or if they "drank heavily for at least one or two days."

Data analysis first dichotomized CES-D scores to compare relapse rates among participants with scores of 16 or higher with those who had scores of 15 or lower. Subsequent analyses explored the effect of raising the CES-D cutoff point by dividing scores into those that were greater than or equal to the higher cutoff points of 24 and 32, those below the new cutoff points but at or above 16, and those 15 or lower. All results compare participants with scores at or above the upper cutoff points with those whose scores were 15 or lower. Confounding by gender, race, marital status, drug treatment history, and participation in the intervention or standard-care arm of the study was assessed using stratified analyses and Mantel-Haenszel adjusted rate ratios (relative risks). Findings for the one-month follow-up were similar to those at six and 12 months and have been omitted to conserve space.

Results

The 288 intervention-site patients did not differ significantly from the 287 standard-care patients on 20 baseline demographic and drug history variables. Six- and 12-month response rates were 82 percent and 77.2 percent, respectively. When follow-up responders and nonresponders were compared on 20 baseline variables, only race was significantly associated with response at 12 months (81 percent for whites, compared with 70 percent for nonwhites; χ2=7.81, df=1, p=.005).

As for demographic characteristics, 67 percent of the sample were men. The mean±SD age of the sample was 33±9.1 years, with a range from 19 to 77 years. About 33 percent of the sample identified themselves as members of a racial or ethnic minority. Twenty-one percent were married.

Patients' mean±SD score on the SAAST was 22±5.4, well above the standard cutoff point of 10 for alcohol dependence. The mean reported number of drinks per drinking day was 12. Most respondents reported alcohol consumption on two of every three days. About 64 percent had used illicit drugs, most often marijuana or cocaine, in the previous year. The mean number of cigarettes per day at enrollment was 20±11.7.

Overall relapse rates at six months were 55 percent for alcohol, 28 percent for cocaine, and 46 percent for marijuana. Twelve-month rates were 64 percent, 33 percent, and 55 percent, respectively, with 92 percent of respondents reporting daily tobacco use. Stratified rates for intervention and standard-care patients have been reported elsewhere (6).

On average, CES-D data were obtained 15 days after treatment admission. Scores were normally distributed, with a mean of 24.8±12.2. Using 16 as the cutoff point, 75.3 percent scored in the depressed range. CES-D scores were inversely correlated with the number of days since last alcoholic drink (r=-.138, p=.001). Among the 319 participants who were abstinent from alcohol for 21 days or more immediately before the assessment, the mean score was 22.9, with 70.8 percent scoring 16 or higher.

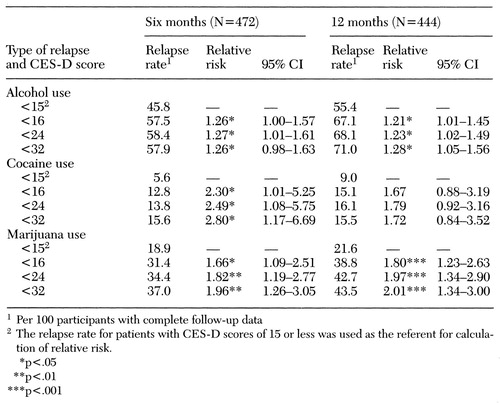

At six months, elevated relapse risks were observed for use of alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana among participants with CES-D scores of 16 or higher (see Table 1). At 12 months, risks were significantly increased for alcohol and marijuana, but the 95 percent confidence interval for cocaine included the null value. Raising the CES-D cutoff point to 24 or 32 resulted in higher relapse rate ratios for marijuana and cocaine, but not for alcohol. Mantel-Haenszel adjusted relative risks yielded no evidence of confounding by race, gender, marital status, drug treatment history, or participation in the intervention or standard-care arm of the study (data not shown).

Discussion and conclusions

The analyses reported here underscore the need to assess depression status in all patients in treatment for alcohol or drug abuse, even though mood and affect often improve with sustained abstinence. Three of every four participants in this study self-reported depression during alcohol treatment. The observed 21 to 28 percent increase in risk for alcohol relapse among depressed patients may appear modest in the context of an individual patient. The finding gains importance, however, when viewed from a public health perspective, given the high prevalence of depression in the drug treatment population.

At six months, elevated depression scores appeared to double the risk of relapse for cocaine use and increase the risk for marijuana use by at least 66 percent. At 12 months, relative risks for cocaine use were lower and no longer statistically significant, but corresponding values for marijuana use had both increased and remained statistically significant. Because we found some evidence that individuals with scores at or above the higher CES-D cutoff points of 24 and 32 faced even greater risks of a relapse to cocaine or marijuana use, it may be worthwhile to consider the score itself, as well as whether or not the score exceeds the traditional cutoff point of 16.

However, interpretation of study findings is limited by several factors. The CES-D is a screening tool, not a diagnostic inventory for depression (10). Increased risk of depression among smokers is well documented, and the percentage of smokers in this study (100 percent by design) is greater than traditionally reported among samples of patients in alcohol treatment (80 to 90 percent). Despite these caveats, we recommend screening all alcohol or drug treatment patients for depression, and, where indicated, providing comprehensive assessment and treatment of this significant comorbid disorder.

Change of Address

Authors of papers under peer review or being prepared for publication in Psychiatric Services are reminded to notify the editorial office at 202-682-6070, or send updated information by fax to 202-682-6189 or by e-mail to [email protected].

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grant AA09233 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to Dr. Bobo.

At the time of the study, all of the authors are affiliated with the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, where Ms. Leed-Kelly is research coordinator in the department of preventive and societal medicine and Dr. McIlvain is associate professor in the department of family medicine. Address correspondence to Dr. Bobo, now an epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Mailstop K-55, 4770 Buford Highway, N.E., Atlanta, Georgia 30341.

|

Table 1. Relative risk of relapse to use of alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana at six and 12 months after discharge from residential drug treatment, by patients' score on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) during residential treatment

1. Dackis CA, Gold MS: Psychiatric hospitals for treatment of dual diagnosis, in Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Edited by Lowinson JH, Ruiz P, Millman RB, et al. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1992Google Scholar

2. Davidson KM, Ritson EB: The relationship between alcohol dependence and depression. Alcohol and Alcoholism 28:147-155, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ziedonis DM, Kosten TR: Depression as a prognostic factor for pharmacological treatment of cocaine dependence. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 27:337-343, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hall SM, Munoz RF, Reus VI, et al: Nicotine, negative affect, and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61:761-767, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Musty RE, Kaback L: Relationships between motivation and depression in chronic marijuana users. Life Sciences 56:2151-2158, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bobo JK, McIlvain HE, Lando HA, et al: Effect of smoking cessation counseling on recovery from alcoholism: findings from a randomized community intervention trial. Addiction, in pressGoogle Scholar

7. McDowell I, Newell C: Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

8. Zich JM, Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK: Screening for depression in primary care clinics: the CES-D and the BDI. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 20:259-277, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Schulberg HC, Saul M, McClelland M, et al: Assessing depression in primary medical and psychiatric practices. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:1164-1170, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, et al: Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. American Journal of Epidemiology 106:203-214, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar