Preventive Health Care for Mentally III Women

Abstract

Utilization of preventive medical care was compared for two low-income groups—47 women with serious mental illness in an urban mental health center and 17 women patients at a primary care center. Appropriate preventive care was defined as at least one physical examination, a Pap test, and a breast examination in the past five years and a mammogram if the patient was over age 40. Receipt of preventive care by women in both settings was similar. Histories of physical and sexual abuse were prevalent in both groups, and a history of abuse was associated with less frequent receipt of preventive care. Results indicate that procedures to identify and provide services to women with abuse histories should be further developed.

Women's health issues have become a prominent focus of attention in the medical literature and lay press. Areas of heightened scrutiny include the risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy and the use of mammograms for women in their 40s. Although the National Cancer Institute has only recently recommended yearly or biannual mammograms for women between the ages of 40 and 50 (1), it has been standard practice for women over age 40 to receive at least one screening mammogram (2).

The health status of women with mental illness has also gained attention in recent years (3,4,5). It has been clearly established that women with severe mental illness are sexually active and need specialized services that address family planning, HIV risk reduction, pregnancy, and childrearing (6,7,8). Although the reproductive needs of women with severe mental illness are being identified and addressed in some settings, it is less clear that other types of routine preventive women's health care are receiving an appropriate level of attention.

For example, in 1985 Handel (9) reported that pelvic examinations of psychiatric inpatients were avoided unnecessarily and that the gynecological needs of mentally ill women warranted further investigation. More than a decade later, it remains unclear whether female psychiatric patients are receiving the basic screening examinations for female cancer—breast and pelvic examinations, Pap tests, and mammograms. These tests are well established as routine health care in the general population, and chronic psychiatric patients may be at increased risk for developing breast cancer (10).

This preliminary study was conducted in an urban community mental health center to determine if female psychiatric patients were receiving preventive health care comparable to that provided to low-income women in a local medical clinic. The purpose of this study was to evaluate access to and utilization of preventive health care to develop mechanisms by which gaps in service could be addressed. Our hypothesis was that women from the mental health center would have less access to routine medical care than other low-income women. We also believed that patients who had been physically abused at any age, sexually abused in childhood, or sexually assaulted as an adult would be less likely to use appropriate health care services.

Methods

The survey was conducted at the Connecticut Mental Health Center, which offers comprehensive inpatient and outpatient psychiatric services to individuals who are indigent and who have serious and prolonged mental illness. The human investigation committee of the affiliated medical school approved the study, which was designed to survey a sample of women receiving psychiatric services and women from a nearby primary care center. Patients from the mental health center and primary care center are drawn from the same impoverished urban environment. A random list of female patients was obtained from five representative clinical programs within the mental health center and two separate programs within the primary care center.

After the researchers received permission from each patient's primary clinician, the patients were approached by an interviewer who was a psychiatric or medical clinician. If patients gave informed consent, the survey instrument was completed during the course of a private interview. The survey included questions on demographic characteristics (age, marital status, health insurance, and number of children), history of preventive health care, history of physical abuse at any age, history of childhood sexual abuse and adult sexual assault, and psychiatric status. Interviews were conducted in 1995.

Data were analyzed using chi square tests and logistic regression analysis with SAS software. Analyses were designed to test two hypotheses: first, that patients of the mental health center would have different patterns of preventive health care than patients of the primary care center, and, second, that women who reported a history of abuse and violence would have different patterns of health care than women who had no history of such abuse. Because these were preliminary data and the sample was small, the significance level was set at p=.10.

Results

Interviews were completed for 71 women—54 from the mental health center and 17 from the primary care center. The mean±SD age was 41.3±12.8 years for the participants from the mental health center and 34.2±15.7 for those from the primary care center. All of the women at the primary care center were insured through Medicaid or Medicare programs. In the sample from the mental health center, 47 women (87 percent) were covered through either Medicaid, Medicare, or a city-run general assistance medical program, and seven (13 percent) had no coverage. Only the psychiatric patients with medical insurance (Medicaid or Medicare) were included in the final sample to ensure that both groups were comparable. Thus the final sample included 64 women.

Patients of the mental health center were compared with patients of the primary care center using chi square tests and odds ratios (OR), which reflect the relative odds of a particular health outcome between the two samples. Patients of the mental health center were more likely than those of the primary care center to have had a general physical examination within the past five years (46 patients, or 98 percent, versus 17 patients, or 94 percent; χ2=6.012, df=1, p=.049). However, for all other preventive care, the rates did not differ between groups.

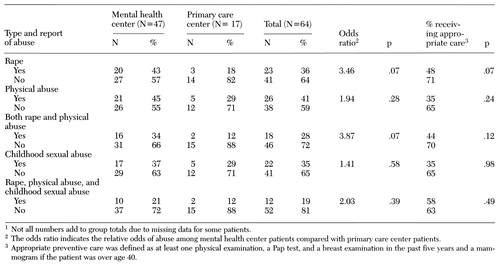

Table 1 shows the associations between various types of abuse and receipt of appropriate preventive care, which was defined in this study as a physical examination, a Pap test, and a breast examination in the past five years and a mammogram if the patient was over age 40. Rape during adulthood was reported by 23 women in the sample (36 percent), with a significantly higher rate among patients of the mental health center than among patients of the primary care center (43 percent versus 18 percent).

Physical abuse was reported by 26 women in the sample (41 percent), and childhood sexual abuse was reported by 22 women (35 percent). Mental health center patients were more likely to report both types of abuse than primary care center patients, but the differences were not significant. Eighteen women in the sample (28 percent) reported the occurrence as adults of both physical abuse and rape. The mental health center patients were nearly four times more likely to report this combination.

Women who had been raped as adults were significantly less likely to receive preventive medical care than those who had not been raped (48 percent versus 71 percent; χ2=3.298, df=1, p=.07). Women who reported both rape and physical abuse were also less likely to receive care than those who did not make such reports (20 percent versus 70 percent), although the difference was not significant.

The 36 women who reported any of the three types of abuse (rape as an adult, physical abuse at any age, and childhood sexual abuse) were half as likely to have received appropriate preventive care as the 28 women who did not report any type of abuse. However, the difference was not significant.

Discussion and conclusions

Access to medical care for the severely mentally ill women at the mental health center was not found to be limited. Most of our center's patients had medical coverage, and contrary to our assumptions, many were receiving appropriate preventive medical care that was comparable to the care received by low-income women seen in a nearby medical clinic. Although seven women in the mental health center sample (13 percent) had no coverage for medical care, they had received physical examinations at the mental health center.

The most pertinent findings were the associations between a history of physical and sexual abuse and a lack of routine preventive health care. The prevalence of all types of abuse—physical abuse, childhood sexual abuse, and rape as an adult—was high in the sample, but mental health center patients were more likely to report one or more forms of abuse than primary care center patients. Although it is heartening that many psychiatric patients receive appropriate medical care, it is alarming to find that regardless of psychiatric history, women who had been victimized were less likely to receive health care services. More detailed examination of this finding with a larger sample is warranted.

The results have important implications for program development and treatment planning. Staff in both mental health and primary care settings should identify women who may have been physically or sexually abused and develop procedures to engage them in the health care system and ensure that appropriate services are utilized.

Dr. Steiner is associate professor of psychiatry, Dr. Hoff is assistant professor of psychiatry, and Dr. Rosenheck is clinical professor of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Ms. Moffett is a program instructor, Ms. Reynolds is associate professor, and Ms. Mitchell is associate clinical professor at Yale University School of Nursing. Send correspondence to Dr. Steiner at the Connecticut Mental Health Center, 34 Park Street, Room 148, New Haven, Connecticut 06508 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper is one of several in this issue focused on women and chronic mental illness.

|

Table 1. Associations between types of abuse and receipt of appropriate preventive care among patients in a mental health center and patients in a primary care center1

1. Kolata G: Another group switches on frequency of mammograms. New York Times, Mar 28, 1997, p A16Google Scholar

2. Sickles EA, Lopans DB: Mammographic screening for women aged 40 to 49 years: the primary care practitioner's dilemma. Annals of Internal Medicine 122:534-538, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Coverdale JH, Bayer TL, McCullough LB, et al: Sexually transmitted disease prevention services for female chronically mentally ill patients. Community Mental Health Journal 31:303-315, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Handel MH, Bennett NM: Development of a program to improve the care of chronically mentally ill women, in Treating Chronically Mentally Ill Women. Edited by Bachrach LL, Nadelson CC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1988Google Scholar

5. Miller LJ, Finnerty ME: Sexuality, pregnancy, and childrearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 47:502-506, 1996Link, Google Scholar

6. Abernethy V, Grunebaum H, Clough L, et al: Family planning during psychiatric hospitalization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 46:154-162, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Coverdale MB, Aruffo JA, Grunebaum H: Developing family planning services for female chronic mentally ill outpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:475-478, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Apfel RJ, Handel MH: Madness and Loss of Motherhood. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

9. Handel M: Deferred pelvic examinations: a purposeful omission in the care of mentally ill women. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:1070-1074, 1985Medline, Google Scholar

10. Halbreich U, Shen JS, Panaro V: Are chronic psychiatric patients at increased risk for developing breast cancer? American Journal of Psychiatry 153:559-560, 1996Google Scholar