Changes in Public Psychiatric Hospitalization in Oregon Over the Past Two Decades

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: In 1988 a governor's commission in Oregon recommended dramatic changes in the state's approach to public psychiatric hospitalization. To evaluate the effect of the recommendations, this study examined characteristics of hospitalization for patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in public psychiatric facilities between 1981 and 1984 and between 1991 and 1994. METHODS: Patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (N=621) were identified as part of a larger study that examined civil commitment in one of Oregon's state hospitals in 1986. Data on the patients' hospitalizations were obtained from a statewide computerized mental health information system. RESULTS: The legal status of hospitalized patients differed between the two time periods, with voluntary hospitalizations overrepresented in 1981-1984 and civil commitments overrepresented in 1991-1994. The locus of hospitalization varied greatly between the two time periods. All hospitalizations in 1981-1984 took place in one of Oregon's three state hospitals. In 1991-1994, subjects were hospitalized in 13 different institutions, including state and community hospitals and specially designed nonhospital inpatient facilities. CONCLUSIONS: Patterns of inpatient hospitalization for public psychiatric patients changed dramatically from 1981-1984 to 1991-1994. The extensive use of community and nonhospital facilities raises questions about monitoring of quality of care in these diverse and decentralized facilities.

The last 50 years have seen the inexorable movement toward the elimination of the state hospital as the cornerstone of inpatient psychiatric care in the United States. From the time of the creation of the National Institute of Mental Health after World War II to the publication of the report of the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health in 1961 (1) and the subsequent establishment of the community mental health centers program (2), the state mental hospital has been targeted for replacement (3,4).

Changes in public mental health service delivery in Oregon mirrored changes on the national level (5). With the introduction of psychotropic medications, state hospital populations declined rapidly from the high levels of the 1950s. Community mental health centers developed in most Oregon counties in the 1970s. During the same period, community hospitals, particularly those in urban areas, developed inpatient psychiatric services. However, up until very recently the state hospitals remained the major provider of inpatient services for public psychiatric patients in Oregon.

In 1988 the governor of Oregon appointed a commission to examine the provision of inpatient psychiatric care to citizens with severe and chronic mental illnesses. The commission's charge was "to recommend a comprehensive plan for the development of improved services" (6). It found significant deficiencies in Oregon's state hospitals, including antiquated facilities, overcrowding, and understaffed units. The commission also noted that acutely ill patients were unable to gain needed hospital-level care on a voluntary basis, resulting in their further deterioration and entry into the civil commitment system. The commission also found that community resources were inadequate to provide community-level care for all patients with chronic mental illness who needed such care.

To rectify these problems, the commission recommended that the state government take immediate steps to improve conditions in state hospitals and redefine the role of the state hospitals to focus on medium- to long-term care. The commission's key recommendation for short-term hospitalization was that the state establish emergency inpatient care in local communities. Hand-in-glove with the recommendation for development of regional acute care facilities was a recommendation to increase residential, crisis, and general outpatient mental health and substance abuse services in the community.

This study examined the impact of the commission's recommendations on psychiatric hospitalization in Oregon by focusing on hospitalization of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The study examined hospital utilization for this group in two four-year time periods before and after the commission's report.

Methods

Subjects were identified as part of a larger study of all patients civilly committed to one of Oregon's three state hospitals in 1986 (N=901). The larger study compared committed patients who went through an administrative override process for treatment refusal with those who did not (7). We obtained data on mental health service utilization for all 901 patients from the computerized statewide mental health information system. The system includes records on hospital episodes dating from the mid-1970s and on community treatment from 1981. For this project we collected data on hospital utilization from January 1980 to November 1995. This paper reports on mental health services received by these subjects in two distinct time periods before and after the commission's report, 1981 through 1984 and 1991 through 1994.

We divided the sample by diagnosis using a diagnostic hierarchy based on information from the records of all hospital episodes for each subject. A subject who had ever received a diagnosis of mental retardation or an organic mental disorder was classified in one of those categories. Among the remaining subjects, those who had received a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder during more than 50 percent of their hospitalizations were classified in one of those categories. This study focuses on subjects with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Results

Sample characteristics

The final sample consisted of 621 patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Fifty-four percent were male. The group was overwhelmingly Caucasian (88 percent), although 7 percent of the subjects were African American. In 1986 a total of 13 percent of subjects were married, 37 percent were divorced, and 50 percent had never been married.

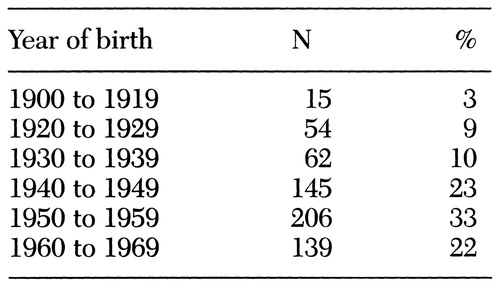

The average age of the group in 1986 was 37 years. Table 1 shows the decades in which the 621 subjects were born. Most subjects were born in the 30-year time span between 1940 and 1969.

A total of 383 subjects, or 62 percent, had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and 238 subjects, or 38 percent, had bipolar disorder. The two diagnostic groups differed significantly in age in 1986. The mean±SD age of the group with schizophrenia was 36±11.8, compared with 40±14 for the group with bipolar disorder (t= 3.695, df=619, p<.001).

Gender and diagnosis were significantly associated. Fifty-two percent of the patients with bipolar disorder were women, and 57 percent of the patients with schizophrenia were men (χ2=5.38, df=1, p=.02). The difference in marital status between the diagnostic groups was highly significant. In the bipolar disorder group, 148 patients, or 65 percent, were either married or previously married, and 81 patients, or 35 percent, had never married. Among the patients with schizophrenia, 147 subjects, or 40 percent, were married or previously married, and 219 subjects, or 60 percent, had never married (χ2= 33.74, df=1, p<.001).

Hospital services

A total of 390 subjects (63 percent of the sample) were hospitalized in either of the two study periods or in both periods. These subjects accounted for 1,627 hospital episodes, with an average of 4.17 hospital episodes per individual. Of the 1,627 episodes, 1,067 episodes, or 66 percent, occurred in 1981-1984 and 560 episodes, or 34 percent, took place in 1991-1994. (Six hospital episodes are missing from this analysis due to missing data on dates of admission and discharge.)

Legal status

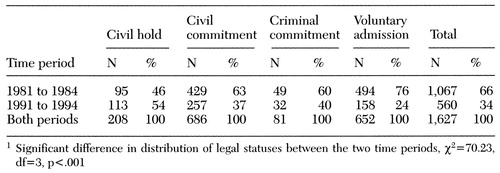

Subjects were hospitalized with one of four legal statuses—voluntary admission or one of three types of involuntary admission. Two of the involuntary categories are components of the Oregon civil commitment process (8)—emergency civil holds (9) and civil commitment itself (10). The third category is a criminal court commitment, used with subjects who are found to be either incompetent to stand trial (11) or guilty except for insanity (12) and who are committed to the jurisdiction of the Psychiatric Security Review Board (13). Overall, 55 percent of the hospitalizations were under the civil commitment statute, 40 percent were voluntary, and 5 percent represented criminal court commitments.

Table 2 shows the legal status for subjects' 1,627 hospital episodes during the two time periods. The percentages of civil and criminal court commitments reflect the proportions of the subjects who were hospitalized during each period—66 percent in 1981-1984 and 34 percent in 1991-1994. However, voluntary subjects are overrepresented in 1981-1984, and civilly committed subjects are overrepresented in 1991-1994. These differences were highly significant.

Locus of hospitalization

The variety and types of settings for hospitalization differed greatly between the two time periods. All of the 1,067 hospitalizations in 1981-1984 took place in Oregon's three state hospitals. The average length of stay for these admissions was 61 days. Forty-six percent were voluntary admissions, 40 percent were for civil commitments, 9 percent were for emergency civil holds, and 5 percent were for criminal court commitments.

By 1991-1994 this situation had changed dramatically. The 560 hospital episodes during that period were divided among 13 different inpatient settings. The settings were the three state hospitals used in 1981-1984; seven general hospital psychiatric inpatient units, including one unit in a university hospital; and three nonhospital inpatient facilities. The nonhospital facilities were originally designed to treat patients who were civilly committed in communities where the general hospitals were not interested in admitting such patients. They now function in a manner similar to general hospital inpatient units.

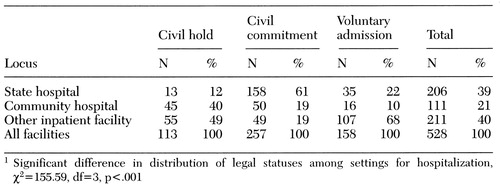

To present these findings more clearly, we combined data from 1991-1994 on the number of patients hospitalized and the length of hospital stay for each of three types of inpatient facilities—state hospitals, community hospitals, and other inpatient facilities.

Table 3 presents data on the number of hospital episodes by hospital type and subjects' legal status. Hospitalizations resulting from criminal court commitments were dropped from these comparisons because they represented a small number of individuals (N=32) and because these hospitalizations took place primarily in the forensic unit of one state hospital during both time periods.

Highly significant differences were found between the groups. Only 39 percent of hospitalizations in 1991-1994 were in the state hospital, 21 percent were in community hospitals, and 40 percent were in nonhospital facilities. The state hospital continued to be the major locus of hospitalization of civilly committed patients, accounting for 61 percent of those hospitalizations for civil commitment. Voluntary hospitalization, which accounted for 46 percent of the total number of hospitalizations in 1981-1984, had fallen to 30 percent of the hospitalizations in 1991-1994. The locus of voluntary hospitalizations also shifted away from the state hospital. In 1991-1994, a total of 68 percent of such episodes took place in nonhospital facilities.

Length of stay

The length of hospital stay in 1991-1994 varied within each legal status and hospital type. For emergency civil holds, the mean±SD length of stay was 5±2.3 days in state hospitals, 6±5 days in community hospitals, and 10±7.7 in other inpatient facilities. For civil commitments, the mean±SD length of stay was 143±175 days in state hospitals, 21±13 days in community hospitals, and 17±12.8 in other inpatient facilities. For voluntary admissions, the mean±SD length of stay was 164±221.9 days in state hospitals, 9±10 days in community hospitals, and 12±9.7 days in other inpatient facilities. Analysis of variance showed that within-group comparisons of average length of stay were highly significant (F=74.244, df=2,506, p<.001).

Hospital services and diagnosis

The number of hospitalizations for patients with schizophrenia did not differ significantly from the number for patients with bipolar disorder. However, patients with schizophrenia had significantly longer hospital stays in both study periods. In 1981-1984 their average length of stay was 124±216.3 days, compared with 68±131.6 days for patients with bipolar disorder (t=3.64, df=619, p<.001, two-tailed). In 1991-1994 their average length of stay was 65±182.8 days, compared with 37±125.4 days for patients with bipolar disorder (t=2.09, df=614, p=.037, two-tailed). The two groups also differed in average length of stay in both time periods combined—subjects with schizophrenia spent an average of 186±323.4 days in the hospital, compared with 105±192.5 days for subjects with bipolar disorder (t=3.51, df=614, p<.001).

Discussion and conclusions

This study focused on hospital services received in two time periods by individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Data for the two periods were drawn from a larger study that examined civil commitment and treatment refusal. Because this study was derived from another project, subjects were not specifically or randomly chosen for representation in the two time periods. Rather, they form a convenience sample of persons with serious illness, and many of them received services in both of the study periods. The data we present do not necessarily reflect general patterns of psychiatric hospitalization in the time periods we studied, but they do provide important leads for further investigation of hospitalization for persons served in Oregon's public mental health system.

Although the main goal of the paper was to describe hospital services in two distinct time periods, the data also show some differences between patients with schizophrenia and those with bipolar disorder. For example, patients with bipolar disorder were more likely to be married. Patients with schizophrenia spent more time in a hospital in both study periods. We have no clear explanation for the finding that significantly more men had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and significantly more women had bipolar disorder; we found a similar distribution of diagnoses in a population of civilly committed patients who had refused treatment (14).

The data allow us to examine the effects of the recommendations of the governor's commission on psychiatric inpatient services in Oregon. The commission's main recommendation—that the state establish emergency inpatient care in local communities—was carried out. In 1981-1984 hospitalizations took place in state hospitals. By 1991-1994 more than 60 percent of hospitalizations took place outside of state hospitals, although longer hospital stays, mainly for patients who had been civilly committed, continued to be the responsibility of the state hospitals.

Other recommendations of the commission, however, have not been implemented. Voluntary hospitalizations, seen by the commission as a way to prevent further deterioration of acutely ill patients, did not become more readily available. The proportion of hospitalizations that were voluntary fell from 46 percent in 1981-1984 to 28 percent in 1991-1994.

In addition, hospital stays for emergency civil holds increased from 9 percent of all hospitalizations in 1981-1984 to 20 percent in 1991-1994. It is possible that voluntary hospitalization occurred outside of the state system. However, we know anecdotally that the whole Oregon system had shifted in the direction of involuntary treatment. If our findings reflect an actual shift in this direction, they raise questions about the consequences of decreased voluntary admissions and an increase in civil holds. The effects of this shift constitute an important area for follow-up. Certainly entry into the civil commitment process carries a great deal more stigma than does a voluntary psychiatric admission.

Changes in the locus of hospitalization also raise important questions. Sixty-one percent of hospitalizations took place outside of the state hospital in 1991-1994, and the majority of these hospitalizations—66 percent—were in nonhospital inpatient facilities. Only 34 percent took place in community hospitals. These findings are noteworthy because of concerns about the quality of care in nonhospital facilities. Community hospitals must meet the standards of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, but nonhospital facilities are regulated according to state rather than national standards. Some of the same problems that the state had in maintaining the quality of care in state hospitals may now exist in community-based nonhospital facilities. As nonhospital facilities replace state hospitals as the main locus of care and inpatient care becomes more decentralized and perhaps less subject to oversight, quality-of-care issues in nonhospital facilities deserve careful attention.

Differences in length of stay by legal status and type of inpatient facility also need further investigation. Are the differences among facilities related to patient selection or to differences in treatment philosophy? If treatment philosophy is a prominent feature, then questions of quality and consistency of treatment approach should also be examined.

The growth in the number of regional inpatient units raises new problems in relation to the role and responsibility of the state in oversight. These problems are common in our time, where state oversight of publicly oriented programs is replacing federal oversight and where privatization is the rule. Such activities are not inherently good or bad. They merely present us with a whole new set of questions for examining the quality of public mental health care.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Oregon Mental Health and Developmental Disability Services Division for help in developing this project.

The authors are affiliated with the office of the dean and the department of psychiatry at the School of Medicine, Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland. Dr. Reichlin is also affiliated with Oregon State Hospital in Salem. Address correspondence to Dr. Bloom, School of Medicine, Oregon Health Sciences University, 3181 Southwest Sam Jackson Park Road, Portland, Oregon 97201.

|

Table 1. Years of birth of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (N=621) for whom data on public psychiatric hospitalization in Oregon were available

|

Table 2. Legal status of patients (N=390) with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder during 1,627 episodes of hospitalization in public psychiatric facilities in Oregon, 1981 to 1984 and 1991 to 19941

|

Table 3. Locus of hospitalization of patients on emergency civil holds, civilly committed patients, and voluntary admissions during 528 episodes of hospitalization, 1991 to 19941

1. Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health: Action for Mental Health. New York, Basic Books, 1961Google Scholar

2. Foley HA, Sharfstein S: Madness and Government. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1983Google Scholar

3. Solomon HC: The American Psychiatric Association in relation to American psychiatry, in New Directions in American Psychiatry, 1944-1968. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1986Google Scholar

4. Greenblatt M, Glazier E: The phasing out of mental hospitals in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry 132:1135-1139, 1975Link, Google Scholar

5. Bloom JD, Cutler DL, Faulkner LR, et al: The evolution of Oregon's Public Psychiatry Training Program. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 44:113-121, 1989Google Scholar

6. Improving the Quality of Oregon's Psychiatric Inpatient Services. Salem, Governor's Commission on Psychiatric Inpatient Services, 1988Google Scholar

7. Bloom JD, Williams MH, Hornbrock M, et al: Treatment refusal procedures and service utilization. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 25:349-357, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

8. Oregon Revised Statutes, Chpt 426: Mentally Ill and Sexually DangerousGoogle Scholar

9. Faulkner LR, McFarland BM, Bloom JD: An empirical study of emergency commitment. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:182-187, 1989Link, Google Scholar

10. Bloom JD, Williams MH: Oregon's civil commitment law:140 years of change. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:466-470, 1994Google Scholar

11. Oregon Revised Statutes 161.360-161.370Google Scholar

12. Oregon Revised Statutes 161.290Google Scholar

13. Bloom JD, Williams MH: Management and Treatment of Insanity Acquittees: A Model for the 1990s. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

14. Godard SL, Bloom JD, Williams MH, et al: The right to refuse treatment in Oregon: a two-year statewide experience. Behavioral Sciences & the Law 4:293-304, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Deci PA, McDonel EC, Semke J, et al: Downsizing state psychiatric hospitals, in Innovative Approaches for Difficult-to-Treat Populations. Edited by Henggeler SW, Santos AB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar