Psychosocial Characteristics of Pregnant and Non pregnant HIV-Seropositive Women

Abstract

Thirty-three HIV-positive women, 12 of whom were pregnant, participated in semistructured interviews to define areas of psychosocial need. Eighty-eight percent of the subjects reported current unemployment. A history of substance abuse was reported by 82 percent, suicide attempts by 52 percent, and sexual problems by 43 percent. Approximately 30 percent reported elevated levels of depressive symptoms on standardized symptom inventories. The pregnant women appeared psychologically healthier than the nonpregnant group. HIV-positive women face multiple psychosocial stressors and may experience significant psychological distress.

Compared with men who are HIV positive, HIV-positive women are more likely to be members of ethnic minority groups, welfare recipients, and socioeconomically disadvantaged (1). Often victims of poverty and inner-city chaos as well as HIV, these women constitute an underserved, underecognized subgroup among the population affected by the HIV epidemic. The psychosocial experience of HIV-positive women is further complicated by the increased risk for depression among women (2); by dilemmas posed by pregnancy, including potential vertical transmission of HIV and risk of maternal mortality before offspring reach maturity; and by peri- and postpartum depression (3).

Systematic reports of psychiatric symptoms among HIV-positive women are few. Brown and Rundell (4) found high rates of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (41 percent) and depressive disorders (16 percent) in an atypical sample of 20 primarily white, employed, and drug-free military women. Lipsitz and colleagues (5) assessed 39 HIV-positive and 37 HIV-negative women who used intravenous drugs and found elevated rates of depressive disorders in both groups (26 percent and 30 percent, respectively). They concluded that drug use may predict depression better than HIV. In a study of 15 obstetric patients who were HIV positive, James (6) described elevated rates of mood disorders (20 percent), substance abuse and dependence (87 percent), and prior suicide attempts (27 percent).

The study reported here compared psychosocial characteristics of pregnant and nonpregnant HIV-positive women. We hypothesized that both groups would experience socioeconomic deprivation, impaired sexual functioning, and elevated rates of depressive symptoms but that the pregnant group, facing additional emotional and social burdens, would experience greater psychosocial impairment and depressive symptomatology.

Methods

Thirty-three female subjects, 12 of whom were pregnant, were recruited from advertisements at self-help organizations and a tertiary care hospital in New York City. Exclusion criteria—inability to speak English or to travel to our research setting—eliminated only one potential subject. After providing written informed consent, subjects participated in a semistructured interview that requested information about their demographic, medical, obstetrical, and psychiatric history. (Copies of the interview instruments are available from the authors.) Subjects were interviewed a second time a mean±SD of 5.4±3.9 months after the first interview. All subjects who were pregnant at the first interview participated in the second interview after they had given birth. Subjects received $20 compensation for each interview.

The 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D) (7), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (8), the Global Assessment Scale (GAS), and the Sexual Function Questionnaire (Goggin KJ, Rabkin JG, unpublished manuscript, 1995) were administered at both interviews. On the Ham-D and BDI, higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. On the GAS, lower scores indicate poorer functioning. Data expressed as means were compared with t tests, and differences in frequencies of categorical measures were tested with chi square or Fisher's exact tests.

Results

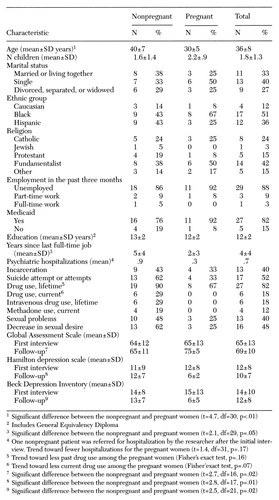

As Table 1 shows, subjects were typically African American or Hispanic, unemployed, single, receiving medical assistance, and living with at least one child. The pregnant and nonpregnant women did not differ on any measure, except that the pregnant group was a mean of a decade younger and reported shorter intervals since the last full-time job. Rates of unemployment were similar in the two groups.

The pregnant women tended to be more likely to return for the second interview than the nonpregnant women. Ten of the 12 pregnant women, or 83 percent, and 13 of the 21 nonpregnant women, or 62 percent, returned for the follow-up (Fisher's exact test=.26).

Subjects were relatively healthy with few HIV-related medical problems. Their mean time since receiving a diagnosis of HIV was 3.5 years, with a range from .1 to 12 years. Twenty-nine subjects, or 88 percent, reported contracting the virus sexually, through unsafe sex or sex work for drugs. Pregnant and nonpregnant subjects did not differ on medical health or HIV-risk variables.

Subjects reported elevated rates of substance abuse, mood symptoms, suicide attempts, and prior psychiatric hospitalizations. Pregnant subjects tended toward fewer psychiatric hospitalizations and tended to be less likely to report past or current drug use, compared with nonpregnant subjects.

We used cutoff scores of 15 on the Ham-D and 17 on the BDI to indicate moderate to severe levels of depressive symptoms. At the initial interview, nine subjects, or 27 percent, had elevated scores on the Ham-D, and ten subjects, or 30 percent, had elevated scores on the BDI. At follow-up, six subjects, or 26 percent, and five subjects, or 22 percent, had elevated scores on the two instruments. Mean initial Ham-D, BDI, and GAS scores did not differ between the pregnant and nonpregnant groups. At follow-up, the postpartum group had significantly lower Ham-D and BDI scores and significantly higher GAS scores.

Ham-D and BDI scores did not change significantly within either group from initial interview to follow-up. However, Ham-D and BDI scores tended to drop in the pregnant group (t=1.8, df=7, p=.12 for the Ham-D, and t=2, df=7, p=.08 for the BDI). GAS scores rose significantly in the pregnant group from intake to follow-up (t=2.6, df=7, p=.04).

Discussion and conclusions

For many women in the study, HIV is not the most pressing problem in their lives, a finding that supports earlier research (1). The challenges of living with HIV can seem small next to the stresses of unemployment, single parenthood, inadequate education, social isolation, and drug addiction. The subjects helped identify several themes to consider when treating HIV-positive women.

Socioeconomic status.

Eighty-eight percent of the subjects were unemployed Medicaid recipients, and 61 percent were caring for at least one child. These findings suggest that this population requires aggressive social and financial support to minimize the impact of socioeconomic deprivation. Assistance with entitlements and child care and vocational counseling may be invaluable.

Substance abuse.

In this sample, 82 percent reported prior drug use, including use of cocaine, heroin, crack, marijuana, and hallucinogens. Because active substance abuse complicates the courses of both HIV and pregnancy, treatment of addictions and their sequelae may be indicated for many patients.

Depression.

The prevalence of major depressive disorders has been estimated at 6 percent in a general sample of women (2) and 5 to 8 percent among HIV-positive men (9). By contrast, the women in the sample showed elevated rates of depressive symptoms—22 to 30 percent—as established by two standard, independent measures, albeit not diagnostic measures. This finding is probably multiply determined: women carry twice the lifetime risk for depression as men (2,3), mood disorders are highly comorbid with substance abuse (5), and lower levels of income and education are correlated with depression (2).

Sexual dysfunction.

Subjects reported decreased sexual desire and high rates of nonspecific sexual problems, findings that support those of Brown and Rundell (4). The psychology of contracting or transmitting HIV through sexual intercourse may exacerbate depression-related decreases in libido.

Participation.

The high rate of attrition between the two interviews (30 percent) is typical of our experience with HIV-positive women. In medical settings and psychotherapy research trials, HIV-positive women also have difficulty attending regularly scheduled appointments (10). Despite tenacious efforts to recruit subjects for second interviews, we recorded multiple late, rescheduled, and ultimately missed appointments. The instability of the subjects' schedules suggests that successful treatment for HIV-positive women may be especially challenging.

Effects of pregnancy.

The pregnant subjects appeared to be psychologically healthier than the nonpregnant subjects. They had briefer periods of unemployment, lower Ham-D and BDI scores and higher GAS scores at follow-up, and trends toward less psychiatric hospitalization, drug use, and attrition. A possible explanation is that the sample was skewed toward more intact individuals who had successfully gained access to tertiary-level medical services. Perhaps the individuals who were most overwhelmed—too distressed to volunteer for a research study—remained undetected by our sampling procedures.

Among the study's limitations are the small sample size and high attrition rate, which limit statistically meaningful comparisons. Lack of formal psychiatric diagnoses precluded definitive determination of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Because the sample was relatively healthy, these findings might not generalize to a medically sicker cohort.

Despite these limitations, the study findings offer further evidence that pregnant and nonpregnant women who are HIV positive face psychosocial challenges that complicate the already impressive demands of a chronic, debilitating illness.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a fund established in the New York Community Trust by DeWitt Wallace and by grants MH-46250 and MH-49635 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Ellen Landsberger, M.D., and Kathleen McGuiness, C.N.P., M.P.H.

Dr. Swartz is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Dr. Markowitz is associate professor of clinical psychiatry and Dr. Sewell is research associate in psychiatry at Cornell University Medical College. Address correspondence to Dr. Swartz at the Depression and Manic Depression Prevention Program, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 3811 O'Hara Street, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Psychosocial characteristics of 21 nonpregnant women and 12 pregnant women who are HIV positive1

1. Ward MC: A different disease: HIV/AIDS and healthcare for women in poverty. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 17:413-430, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, et al: The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the national comorbidity survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:979-986, 1994Link, Google Scholar

3. Weissman MM, Olfson M: Depression in women: implications for healthcare research. Science 269:799-801, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Brown GR, Rundell JR: A prospective study of psychiatric aspects of early HIV disease in women. General Hospital Psychiatry 15:139-147, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lipsitz JD, Williams JBW, Rabkin JG, et al: Psychopathology in male and female intravenous drug users with and without HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1662-1668, 1994Link, Google Scholar

6. James ME: HIV seropositivity diagnosed during pregnancy: psychosocial characterization of patients and their adaptation. General Hospital Psychiatry 10:309-316, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 25:56-62, 1960Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelsohn M, et al: An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 4:561-571, 1961Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Atkinson JH, Grant I: Natural history of neuropsychiatric manifestations of HIV disease. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 17:17-33, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Swartz HA, Markowitz JC: Interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of depression in HIV-positive men and women, in American Psychiatric Press Review of Psychiatry, vol 17. Edited by Oldham JM, Riba MB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1998Google Scholar