A Comparison of Federal Definitions of Severe Mental Illness Among Children and Adolescents in Four Communities

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Using data from an epidemiological survey, the study compared existing definitions of severe mental illness and serious emotional disturbance among children and adolescents to demonstrate the range of prevalence rates resulting from application of different definitions to the same population. METHODS: Three definitions of severe mental illness and serious emotional disturbance were applied to data from the Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders survey, with a sample of 1,285, conducted in 1991-1992 by the National Institute of Mental Health. The resulting proportions of cases identified, demographic characteristics, service use, and perceived need for services were compared. RESULTS: From 3 to 23 percent of the sampled youth met criteria for severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance. From 40 percent to as many as 78 percent of the defined youth used a mental health service in the year before the survey. School and ambulatory specialty settings were used most frequently. Generally, more than half of the parents of children with severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance thought that their child needed services. CONCLUSIONS: The prevalence and characteristics of severe mental illness and serious emotional disturbance among children are sensitive to the definition used and its operationalization. Care should be taken by policy makers and service planners to avoid either over- or underestimating the prevalence of impaired youth in need of intensive interventions.

Children with severe mental illness and serious emotional disturbance have long been targeted as having special service needs in the mental health and education service sectors (1,2,3,4,5). Efficient planning for these services requires a solid foundation in epidemiologic data. These data can provide population-based estimates of the prevalence of mental disorders, disabilities, and competencies, as well as service use across a variety of settings (6,7,8,9). In the United States, the absence of quantitative information on the rates associated with different definitions of need has been a hindrance to organizing and providing appropriate services (4,10).

Epidemiologic data could be used in the empirical development and testing of definitions of severe mental illness and serious emotional disturbance. Several definitions have been developed for children and adolescents by various agencies for different purposes (11,12). In the study reported here, several definitions of severe mental illness and serious emotional disturbance were applied to data from the Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) survey conducted by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to demonstrate the range of rates resulting from the application of different definitions to the same population (13).

The definitions used

Three definitions of severe mental illness and serious emotional disturbance among children and adolescents are in wide use for clinical and policy purposes. The first is the definition of severe mental illness set forth by the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations in the appropriations bill for the Department of Health and Human Services for fiscal year 1993. The bill states: "Severe mental illness is defined through diagnosis, disability and duration, and includes disorders with psychotic symptoms such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, manic depressive disorder, autism, as well as severe forms of other disorders such as major depression, panic disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder." This definition was used in the 1993 National Advisory Mental Health Council report entitled "Health Care Reform for Americans With Severe Mental Illnesses" (1).

Since the publication of this report, the MECA collaborators have refined the report's basic diagnostic and service use algorithms for use in the survey. The results reported in this paper are therefore updates of the preliminary estimates included in the advisory council's report.

The second definition is based on the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (P.L. 94-142), originally passed in 1975, which is used in educational settings to define emotional disturbance. This definition has been criticized for its vagueness and outmoded terminology, and some states have developed criteria based on IDEA that are more specific and easier to put into practice (12,14,15). This study used the criteria developed for the Texas Interagency Children's Mental Health Initiative (16). To meet criteria for serious emotional disturbance, the child or adolescent:

"Must have (I, II, & III) or (I, II, & IV) or V

I. Diagnosis—DSM-III R axis I or II diagnosis, except a single diagnosis of psychoactive substance use disorder, developmental disorder, or V code. Organic mental disorders are included only while behaviors are a danger to self or others.

II. Risk of or separation from family

1. Chronic family dysfunction involving a mentally ill and/or inadequate caretaker, or multiple agency contact, or changes in custodial adult; or

2. going to, residing in, returning from any out-of-home placement, e.g., psychiatric hospital, short-term inpatient, residential treatment, group or foster home, corrections facility, etc.

III. Functional impairments or symptoms. Must have A or B:

A. Functional impairment. Must have substantial impairment in two of the following capacities to function (corresponding to expected developmental level):

1. Autonomous functioning.

2. Functioning in the community.

3. Functioning in the family or family equivalent

4. Functioning in school/ work.

B. Symptoms. Must have one of the following:

1. Psychotic symptoms.

2. Suicidal risk.

3. Violence. At risk of causing injury to person or significant damage to property, due to mental illness.

IV. History. Without treatment, there is imminent risk of decompensation or separation from family in Section II above.

V. Special education students. Special education students who have been assessed as being seriously emotionally disturbed and have identified mental health needs in their individualized education plans."

Third is the definition of serious emotional disturbance contained in the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration Reorganization Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-321), which employs a concept of diagnosis plus functional impairment: "children with a serious emotional disturbance are persons from birth to age 18 who currently or at any time during the past year have had a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder of sufficient duration to meet diagnostic criteria specified within DSM-III-R that resulted in functional impairment which substantially interferes with or limits the child's role or functioning in family, school, or community activities." The ADAMHA Reorganization Act also includes among seriously emotionally disturbed children those "who would have met functional impairment criteria during the referenced year without the benefit of treatment or other support services."

Methods

The MECA Survey

The Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) survey was conducted in 1991-1992 through a cooperative agreement between NIMH and four universities: Columbia University in New York City, Emory University in Atlanta, the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan, and Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. The main purpose of the study was to develop and test instruments and methods suitable for future large-scale epidemiologic studies of mental disorders among children and adolescents (13). The four survey areas were chosen for their diversity in socioeconomic characteristics, culture, and ethnicity, as well as for their geographic convenience to the university sites.

The target population at each site was all youths age nine to 17 years residing in housing units within the geographic area. Youths residing in institutions were therefore excluded from the sample. If more than one eligible youth resided at a selected housing unit, one was randomly chosen. Both youth and adult respondents (parents) were required to speak English or Spanish as their primary language. More than 99 percent of households contacted at each site agreed to be enumerated. Overall, 84.4 percent of the eligible youth-parent pairs were interviewed. The combined sample size for the four field sites was 1,285 youth-parent pairs. The development of the instruments used in the study and their psychometric characteristics have been outlined in previous publications (17,18,19,20,21).

Diagnoses of mental and addictive disorders were obtained by computer algorithms using symptom data from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, 2nd version, revised (DISC-2.3), a structured psychiatric interview suitable for administration by lay interviewers in community settings (18). Diagnostic criteria were set forth in DSM-III-R (22). Diagnoses were based on an algorithm that combined data from parents' and youths' responses to the DISC-2.3. A positive symptom report from either the parent or the youth counted toward the diagnosis (18).

The DISC-2.3 did not include a specific module for schizophrenia but instead included screening questions for psychosis. Respondents who gave an affirmative response to a screening question about a psychotic symptom were asked an open-ended question that requested more information about the symptom. MECA clinicians subsequently read the responses and judged whether the respondents' descriptions represented a probable, possible, or unlikely psychotic symptom. Only the symptoms coded as probable by the MECA clinicians were used in the computer algorithm module for psychosis.

In addition to the questions about impairment included in the DISC-2.3, the Child Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) (17) was used as a measure of functional impairment in some analyses. The CGAS score is chosen from a continuous scale ranging from 1, extremely impaired, to 100, doing very well. The CGAS score used was the lower of the two scores reported by the parents' interviewer and the youths' interviewer, a convention used in previous MECA data analyses.

Data on services used in the past year were grouped by sector: ambulatory and inpatient specialty mental health and addiction services, general medical services, school-based services, and human services (19,23,24). The specialty mental health and addiction services sector and the general medical services sector were grouped together and referred to as the health systems sector (23,24). Parents' perception of their child's need for mental or addictive services was assessed through the question, "Do you think [name of youth] currently needs any kind of help for emotional or behavior problems, or for the use of alcohol or drugs?"

Application of definitions to MECA data

The choice of diagnoses and severity criteria for the operationalization of the Senate Appropriations Committee's definition was based on previously published work (1). As a proxy for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, the DISC-2.3 screen for psychosis was used in the analyses. Autism was not measured in the DISC-2.3.

Children who had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, or who met criteria on the psychosis screen, were considered severely mentally ill if there was further evidence of severity. Severity criteria included one or more of the following within the past year: any inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, any outpatient mental health treatment in a specialty mental health or general medical setting, psychotic symptoms (corresponding to criterion A of DSM-III-R schizophrenia, which was contained in the psychosis module), use of antipsychotic medication, or a CGAS score of 50 or less ("obvious problems"). Children with major depressive disorder, panic disorder, or obsessive compulsive disorder were considered severely mentally ill if one or more of the following severity criteria were met: inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, psychotic symptoms, use of antipsychotic medication, or a CGAS rating of 50 or less.

The operationalization of the second definition, which is based on the Texas Mental Health Initiative's application of IDEA, required the use of multiple scales and questions from the MECA interviews (18,21). A list of the items used for the analyses is available from the first author.

In the third definition of serious emotional disturbance, which was contained in the ADAMHA Reorganization Act, diagnosis with substantial interference or limitation in functioning was operationalized as the presence of a DISC-2.3 diagnosis with a specified level of global impairment on the CGAS. Youths were characterized into three groups on the basis of their CGAS scores. The first group had CGAS scores of 70 or less ("some problems"), the second group had scores of 60 or less ("some noticeable problems"), and the third group had scores of 50 or less ("obvious problems"). To account for youths who would have met functional impairment criteria if they were not receiving treatment or other support services, youths with any DISC-2.3 disorder in the past six months who used any services within the past year but who did not meet the specified CGAS cutoff were also considered to meet the definition for serious emotional disturbance.

Statistical analysis

Unweighted data from all MECA study sites were combined for use in the analyses. Age and gender distribution, race or ethnicity, household income, and the youths' insurance status were determined for each of the three definitions of severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance. The distribution of each demographic factor for each definition was compared to the distribution of the overall MECA sample using a chi square goodness-of-fit test (25).

We tabulated the percentage of the MECA sample to whom each of the three definitions applied, as well as the percentage of the sample in each major diagnostic category. Mental health service use in the past year and parent's perceived level of need for mental health or substance use treatment services for the child were calculated. Comparisons across definitions were made using McNemar's test; for the diagnostic comparisons of the three ADAMHA Reorganization Act groups, one-tailed binomial z tests were used (26).

Results

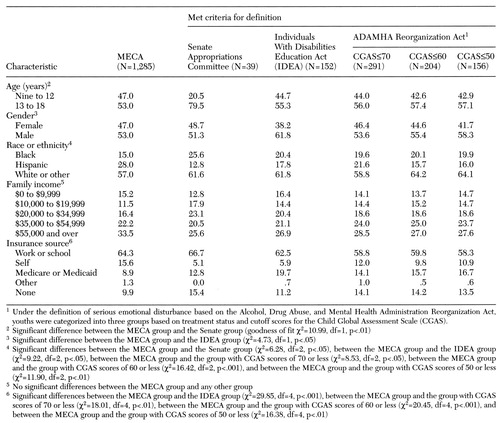

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the overall MECA sample and the five groups that met criteria for severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance based on the various definitions considered in the study. More than 55 percent of the youths in each group were in the 13- to 18-year age range; 80 percent of the youths who met the Senate criteria were in this age group. Males accounted for 50 to 60 percent of each group, with a significantly higher percentage of males meeting IDEA criteria. Compared with the distribution of racial and ethnic groups in the MECA sample, Hispanics were relatively underrepresented, and blacks and, to a lesser degree, whites were overrepresented across all the study groups.

The proportion of youths with insurance coverage was significantly different between the MECA sample and four of the five study groups. Although a majority of the children with severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance had insurance coverage through their parents' work or school, relatively more of those children were insured through Medicare or Medicaid, or were uninsured, compared with the overall MECA sample. There were no significant differences in income distributions between the five groups.

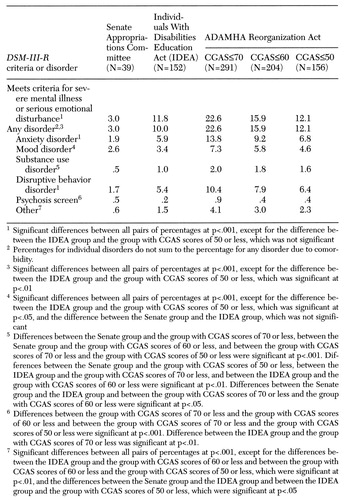

The percentage of youths in the MECA sample who met the criteria in each definition of severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance is presented in Table 2. As expected, significantly fewer children met the criteria of the Senate Appropriations Committee for severe mental illness (3 percent), compared with the percentage who met criteria in the other four groups. Approximately 12 percent of the sample met the IDEA criteria for severe emotional disturbance. A similar percentage met the criteria in the ADAMHA Reorganization Act and had a CGAS score of 50 or less.

With progressively lower CGAS cutoff scores, the percentage of children meeting the criteria in the ADAMHA Reorganization Act declined from 22.6 percent for CGAS scores of 70 or less to 12.1 for CGAS scores of 50 or less. The group who met the criteria for this definition included unimpaired children who were in treatment. Children in treatment who did not meet the CGAS impairment cutoff contributed relatively more to the overall prevalence of serious emotional disturbance as the CGAS cutoff became more stringent.

For example, when the CGAS cutoff point was set at 70, a total of 7 percent (19 of 291) of the children who met the ADAMHA criteria for serious emotional disturbance had scores above the CGAS cutoff point but met the definition because they were receiving treatment. When the CGAS cutoff point for the definition was set at 60, the unimpaired but treated group constituted 27 percent (55 of 204) of the children who met the criteria. When the CGAS cutoff point was set at 50, this group increased to 54 percent (85 of 156) of the children who met the criteria.

Table 2 also shows that all children who met criteria for severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance also had a DISC-2.3 disorder within the previous six months except for 24 children (1.8 percent of the MECA sample) in the IDEA group; they were included in the group solely due to meeting criterion V of the Texas definition, that is, enrollment in special education programs. Because of the lower overall prevalence associated with the Senate definition, this group had significantly lower prevalences of anxiety, mood, disruptive behavior, and "other" disorders. Overall, few children had a positive psychosis screen, with the ADAMHA group with a CGAS score of 70 or less having a significantly higher rate (.9 percent) than the other groups.

As for the distribution of each diagnostic grouping, anxiety disorders and disruptive behavior disorders were the predominant disorders in each group. An exception was the group who met the Senate criteria for severe mental illness. Mood disorders were found among more than 87 percent of this group. In other groups, mood disorders were found among 30 to 40 percent of the youths. Substance use disorders were less frequent, ranging from 15.4 percent of the group who met Senate criteria to 8.6 percent of the group who met the IDEA criteria. Psychosis was found in varying percentages of each group, from 1.3 percent of the youths in the IDEA group to 15.4 percent of the youths in the Senate group.

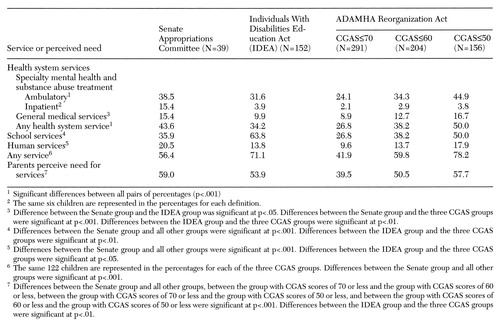

Table 3 shows mental health service use in the past year by the youths in each group and parents' perception of current need for mental health or substance use treatment services. The percentage of children using any mental health service ranged from 78 percent (youths who met the ADAMHA criteria who had a CGAS score of 50 or less) to 42 percent (youths who met the ADAMHA criteria who had a CGAS score of 70 or less). Ambulatory specialty services were used by 24 to 45 percent, and school-based services were used by 27 to 64 percent.

Six children used inpatient services in the past year. They met criteria for each definition of severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance. Because of the differing base rates of each definition, the six children represent different proportions of the five study groups, from 15.4 percent of the children meeting Senate criteria to 2.1 percent of children meeting the ADAMHA criteria with a score of 70 or less. As expected, youth in the IDEA group had higher rates of school service use. None of the groups had a utilization rate of more than 17 percent for general medical services for mental health reasons, surprisingly low compared with usage rates by adults with severe mental illness (1). Among the group who met the ADAMHA criteria, the percentage of children with service use in all sectors decreased as the CGAS score increased. This trend was due to the addition of children not in treatment as the CGAS cutoff increased, because the same 122 children who received treatment are represented in the percentages for each of the three ADAMHA groups.

More than half of interviewed parents saw a current need for services for their child, except for parents of youth in the group with a CGAS score of 70 or less, of whom 40 percent saw a need for services. All comparisons of perceived need between the study groups were statistically significant.

Discussion

First, limitations of the MECA data set should be mentioned. Although each MECA site comprised a random probability sample of a defined geographic area, differences in sampling methods between sites prevented weighting of pooled data. Hence, the proportions resulting from these unweighted data are not representative of a larger population. Time frames differed for diagnosis (past six months) and service use (past year), with the result that children with a diagnosis in the first, but not the second, six months of the year may not have been counted in the analyses. The new DISC-4 incorporates a one-year time frame that better accommodates most service planning needs. Finally, the DISC-2.3 psychosis screen provided only a rough estimate of psychotic syndromes. Still, after clinician judgments of symptom veracity and the severity criteria in the definitions of severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance were used, plausible estimates in the range of .5 percent or less were obtained.

The proportions of the MECA sample meeting criteria for one of the categories of severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance generally fell within the range of previous studies. The U.S. Center for Mental Health Services, in a review of various population-based child and adolescent mental health surveys, concluded that 9 to 13 percent of children and adolescents aged nine to 17 could be characterized as seriously emotionally disturbed, with a more stringent definition of impairment lowering the prevalence to 5 to 9 percent (27). These estimates did not specifically include children with mental disorders who were in treatment but did not meet the CGAS cutoff points used in the analyses.

In our operationalization of criteria in the ADAMHA Reorganization Act, we attempted to include children who were in treatment but did not meet the CGAS cutoff points. We found that they contributed substantially to the overall prevalence of serious emotional disturbance, particularly those with a CGAS cutoff score of 50 or less. There is no way to determine from these data how many of the children in this group would have a CGAS score of 50 or less if treatment were withdrawn, so our estimate of 6.6 percent of the total MECA sample (85 of 1,285) is likely to be an overestimate. However, policy makers and mental health planners should be aware that the potential for underestimation of need exists when these children are excluded.

The estimated prevalence of serious emotional disturbance as defined by IDEA among subjects in the MECA survey, 11.8 percent, differs by an order of magnitude from school-based estimates of less than 1 percent to 2 percent (3,5,28). Part of this difference may be attributed to an overly inclusive operationalization of IDEA for the MECA analyses. However, another explanation is that school-based estimates of children with serious emotional disturbance tend to be based on treated prevalence rather than on random survey samples of schoolchildren. With limited resources available to most school districts, it is likely that only the most visibly disabled or disturbing children are identified by schools as needing services, leaving a large number of impaired but unidentified schoolchildren.

It is well known that only a minority of persons with any mental disorder seek treatment (24) and that this minority is even smaller in the case of children and adolescents, particularly for treatment in the specialty mental health sector (8,29). Our findings show that a similar adult-child disparity exists among those with severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance.

To use the most directly comparable example, among adults and children who met criteria for severe mental illness defined by the Senate, 62 percent of the adults sought treatment in the health systems sector in a one-year period, compared with 44 percent of the children. In none of the groups that met criteria for the other definitions did the percentage treated in the health systems sector rise above 50 percent. The overall number of children in treatment does rise when human services and schools are added, but it is questionable whether the services provided in these sectors alone are adequate to treat children meeting criteria for the more severe definitions—that is, the Senate definition and the ADAMHA definition plus a CGAS score of 50 or less.

Conclusions

It is esential for child health policy makers to be aware of the full clinical, service use, and cost implications of their definitions of severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance. This study has provided an objective comparison of the implications of multiple definitions in the same population of children and adolescents.

Definitions of severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance should be inclusive enough to identify children who are in need of intensive services. However, a careful examination of the criteria for functional impairment is critically important to ensure that broader definitions, such as those in the ADAMHA Reorganization Act, do not include children for whom a lower intensity of services is sufficient. On the other hand, strict criteria for impairment such as those in the operationalization of the Senate definition have the potential to exclude children with psychiatric diagnoses and functional impairment who could benefit from the use of more intensive mental health services.

Future epidemiologic and health services research studies should be cognizant of the policy context in which children are receiving mental health and educational services and assure that relevant variables used in defining the need for services are included in the research design. Of greatest help would be longitudinal studies that prospectively examine the longer-term outcome of children with and without specialty services.

Journal Seeks Short Items About Novel Programs

Psychiatric Services invites short contributions for Innovations, a new column to feature programs or activities that are novel or creative approaches to mental health problems. Submissions should be between 350 and 750 words. The name and address of a contact person who can provide further information for readers must be listed.

A maximum of three authors, including the contact person, can be listed. References, tables, and figures are not used. Any statements about program effectiveness must be accompanied by supporting data within the text.

Material to be considered for Innovations should be sent to the column editor, Francine Cournos, M.D., at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Drive, Unit 112, New York, New York 10032. Dr. Cournos is director of the institute's Washington Heights Community Service.

Acknowledgments

The MECA program is supported by grants UO1-MH46725, UO1-MH46718, UO1-MH46717, and UO1-MH46732 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank John Bartko, Ph.D., for statistical consultation.

Dr. Narrow and Dr. Regier are affiliated with the office of the associate director for epidemiology and health policy research, Mr. Rae and Ms Roper are with the division of services and intervention research, and Ms Bourdon is with the division of mental disorders, behavioral research and AIDS at the National Institute of Mental Health in Rockville, Maryland. Dr. Goodman is affiliated with the department of psychology at Emory University in Atlanta. Dr. Hoven and Dr. Moore are with the department of psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and the New York State Psychiatric Institute in New York City. Address correspondence to Dr. Narrow at the National Institute of Mental Health, 31 Center Drive, Room 4A52 (MSC 2475), Bethesda, Maryland 20892 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of children in the Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) survey sample and survey participants who met criteria for three definitions of severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance, in percentages

|

Table 2. Percentage of the MECA survey sample (N=1,285) who met criteria for three definitions of severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance and who met DSM-III-R criteria for various mental disorders

|

Table 3. Percentage of children who met criteria for three definitions of severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance who used services in the past year and whose parents perceived a current need for services

1. National Advisory Mental Health Council: Health care reform for Americans with severe mental illnesses: report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1447-1465, 1993Link, Google Scholar

2. Dougherty DM, Saxe LM, Cross T, et al: Children's Mental Health Problems and Services: A Report by the Office of Technology Assessment. Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 1987Google Scholar

3. Knitzer J, Steinberg Z, Fleisch B: At the Schoolhouse Door: An Examination of Programs and Policies for Children With Behavioral and Emotional Problems. New York, Bank Street College of Education, 1990Google Scholar

4. Forness SR, Hoagwood K: Where angels fear to tread: issues in sampling, design, and implementation of school-based mental health services research. School Psychology Quarterly 8:291-300, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

5. To Assure the Free Appropriate Public Education of All Children With Disabilities: Sixteenth Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC, US Department of Education, 1994Google Scholar

6. Morris JN: Uses of Epidemiology. Edinburgh, Livingstone, 1970Google Scholar

7. Zahner GEP, Pawelkiewicz W, DeFrancesco JJ, et al: Children's mental health service needs and utilization patterns in an urban community: an epidemiological assessment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 31:951-960, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Costello EJ, Burns BJ, Angold A, et al: How can epidemiology improve mental health services for children and adolescents? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 32:1106-1113, 1993Google Scholar

9. Caring for People With Severe Mental Disorders: A National Plan of Research to Improve Services. DHHS pub ADM 91-1762. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1991Google Scholar

10. Costello EJ, Tweed DL: A Review of Recent Empirical Studies Linking the Prevalence of Functional Impairment With That of Emotional and Behavioral Illness or Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, March 1994Google Scholar

11. Davis M, Yelton S, Katz-Leavy J: State Child and Adolescent Mental Health: Administration, Policies, and Laws. Tampa, Florida Mental Health Institute, 1995Google Scholar

12. Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law: Federal Definitions of Children With Serious Emotional Disturbance. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Dec 1993Google Scholar

13. Lahey BB, Flagg EW, Bird HR, et al: The NIMH Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) study: background and methodology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:855-864, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Gonzalez P: A Comparison of State Policy to the Federal Definition of "Serious Emotional Disturbance." Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Directors of Special Education, May 1991Google Scholar

15. National Mental Health Association: New definition of children with emotional disorders published: education department needs to hear support for change. Legislative alert 103-1. Alexandria, Va, National Mental Health Association, 1993Google Scholar

16. Joint Texas Education Agency-Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation Task Force on Emotional Disturbance: Education and Mental Health: Profitable Conjunction. Austin, Texas Education Agency, 1991Google Scholar

17. Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al: A Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Archives of General Psychiatry 40:1228-1231, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan M, et al: The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:865-877, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Leaf PJ, Alegria M, Cohen P, et al: Mental health service use in the community and schools: results from the four-community MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:889-897, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Schwab-Stone ME, Shaffer D, Dulcan MK, et al: Criterion validity of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children version 2.3 (DISC-2.3). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:878-888, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Goodman SH, Hoven CW, Narrow WE, et al: Measurement of risk for mental disorders and competence in a psychiatric epidemiologic community survey: the NIMH Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:162-173, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

23. Narrow WE, Regier DA, Rae DS, et al: Use of services by persons with mental and addictive disorders: findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area program. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:95-107, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Steel RGD, Torrie JH: Principles and Procedures of Statistics. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1960Google Scholar

26. Fleiss JL: Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 2nd ed. New York, Wiley, 1981Google Scholar

27. Friedman RM, Katz-Leavy, JW, Manderscheid RW, et al: Prevalence of serious emotional disturbance in children and adolescents, in Mental Health, United States, 1996. DHHS pub SMA 96-3098. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1996Google Scholar

28. Zill N, Schoenborn CA: Developmental, learning, and emotional problems: health of our nation's children, United States, 1988, in Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics, No 190. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 1990Google Scholar

29. Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Fielding B, et al: Representativeness of clinical samples of youths with mental disorders: a preliminary population-based study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 106:3-14, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar