Health Status and Health Care Costs for Publicly Funded Patients With Schizophrenia Started on Clozapine

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined the effect of clozapine treatment on the health care costs and health status of people with schizophrenia who are supported by public funds. METHODS: Thirty-three patients with schizophrenia hospitalized in a state facility were interviewed within one week of starting clozapine and six months later. Health status was assessed with four clinical rating scales measuring severity of psychopathology, negative symptoms, depression, and quality of life. Cost and health care utilization data were collected for the six months before and after initiation of clozapine. RESULTS: Only 52 percent of the subjects stayed on clozapine for six months. Subjects who continued on clozapine were more likely to be discharged within six months than those who did not continue. Six months after clozapine was started, health care costs showed a savings of $11,464 per person, even after adjustment for pretreatment costs, and health status was improved. CONCLUSIONS: For subjects who continued on clozapine for six months, clozapine treatment was associated with reduced days of psychiatric hospital care, reduced overall costs despite increased outpatient treatment and residential costs, and improved health status.

Michigan has included reduction in days of psychiatric hospital care as a public health criterion (1). However, reduction in hospital stay does not guarantee nor necessarily reflect improved health status.

Patients with schizophrenia that is refractory to traditional treatments have a high hospitalization rate. This patient group, representing 10 to 20 percent of all patients with schizophrenia (2), incurs a large proportion of the total annual estimated cost of treatment for schizophrenia—$33 billion in 1990 dollars (3). One approach to reducing days of psychiatric hospital care for this group is the use of novel antipsychotic medications such as clozapine. Pharmacoeconomic evaluations of clozapine have indicated cost reductions as a result of reduced use of psychiatric hospital care as well as improved health status (4,5,6,7,8,9). However, a concern has been raised (8), and recently confirmed (10), that these gains may be offset by increased use of other parts of the service system, such as intensive outpatient services and supervised residential living.

This study used a prospective cohort design to examine the effects of clozapine treatment on the health care costs and health status of people with schizophrenia who are supported by public funds.

Methods

Inpatients who began clozapine treatment between September 1993 and March 1995 at two long-term state hospitals were consecutively referred by treating psychiatrists for this study. These facilities serve the urban Detroit area and had an average daily census during the study's enrollment period of 510 and 128 patients.

During the 18-month enrollment period, 212 patients initiated clozapine treatment at the two facilities, but only 45 patients met eligibility criteria. The criteria were no previous clozapine treatment within six months of baseline, no participation in any other research protocol, ability to be interviewed within one week of beginning clozapine treatment, Wayne County residency with support by public funds, and informed consent of the patient and guardian, when applicable. There were no exclusionary criteria based on physical or mental comorbidities, including substance abuse. Of the 45 patients referred to the study, 12 refused to be interviewed, a 27 percent refusal rate.

Signed informed consent was obtained at baseline—that is, within one week of beginning clozapine—and again at six months. The six-month interviews were conducted in person where the subject was located, whether in the hospital, a residential facility, or jail. The interviewer at the six-month interview was not aware of whether the subject was taking clozapine. To facilitate tracking subjects for the six-month follow-up, subjects were instructed to call an 800 number biweekly. They received $5 per telephone call and $50 per interview.

Health status was measured at baseline and six months using four clinical rating scales. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (11) was used to rate severity of psychopathology, the Negative Symptom Assessment scale (NSA) (12) was used to measure negative symptoms, the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) (13) was used to measure depression, and the Quality of Life Scale (QLS) (14) was used to determine level of functioning. Ratings were made by a trained doctoral-level psychologist with extensive clinical experience with patients with schizophrenia.

After all the interviews were completed, the interviewer reviewed the hospital medical records of all subjects for a 12-month period beginning six months before the starting date for clozapine treatment and ending six months after the starting date. Patients' demographic and clinical characteristics and information on the course of clozapine treatment were obtained from the medical records.

To assess costs of services from the perspective of public funds, data on patients' service utilization and residential status were collected. The course of each subject's clozapine treatment as described in the medical records was verified using the clozapine national registry system maintained by the U.S. manufacturer of clozapine. Residential status was tracked using a 365-day timeline and was verified using all databases, self-report, and interviews with family members when necessary.

The calculations took into consideration the variation between facilities of charges or government costs. Costs of all medications and blood monitoring were included in inpatient and Medicaid costs, but data for these costs were not available for outpatient mental health services. Medicaid costs also included treatment of physical illness. Pharmacies and nonpsychiatric hospitals were not checked for completeness of reporting to Medicaid. Thus Medicaid costs may be underestimated. Due to the short follow-up period, costs are reported in unadjusted numbers, primarily reflecting 1993 dollars.

SPSS was used for all statistical analyses. Analysis of covariance was used to control for baseline values for health status and costs when the outcome was continuous. Global significance of changes in health status as measured by the four clinical rating scales was obtained using multivariate analysis of variance and, given the small sample size, was confirmed using O'Brien's test (15), a nonparametric test. Because of the small sample size, our ability to detect associations was limited to those with large effect sizes.

Results

Sample characteristics

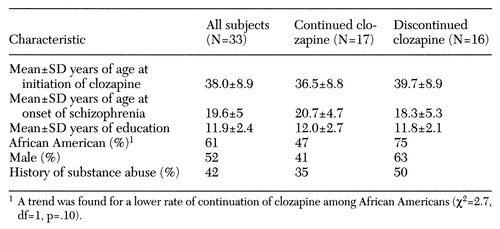

The sample was composed of 33 subjects. Information on health status was available for 29 subjects; four declined the six-month interview. Information on costs was available for all 33 subjects. All subjects met DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia, ascertained from interview and chart review, and all had a disorder that was refractory to at least two different standard antipsychotic medications, according to medical records. They all had been hospitalized multiple times. Demographic and clinical data for the sample are shown in Table 1.

After clozapine was initiated, 17 subjects (52 percent) continued with the medication for six months, and 16 subjects (48 percent) discontinued at a median time of 50 days after initiation (range from five to 164 days). Four subjects who discontinued also did not complete the six-month interview. All but one of the subjects who discontinued were taken off clozapine while hospitalized. Medical records indicated that only one of 16 discontinuations was due to a decrease in white blood cell count; the other patients discontinued the drug for a variety of reasons. Patients who discontinued clozapine were started on diverse antipsychotic medications, both typical and atypical, with no single medication predominant.

The continuation and discontinuation groups showed no differences in demographic or clinical characteristics except for a trend of a lower rate of continuation of clozapine among African Americans (χ2 =2.7, df=1, p= .10). No large differences between continuation and discontinuation groups were found on individual clinical rating scales at baseline except for a trend for subjects who continued on clozapine to have had higher baseline NSA scores (t=1.86, df=27, p=.07). This difference was not due to confounding by race, as there was no association between race and NSA scores.

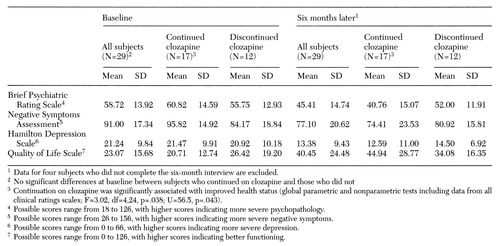

Health status

Table 2 shows subjects' scores on clinical rating scales at baseline and follow-up. Use of global parametric and nonparametric tests on all ratings scales together showed that continuation on clozapine was significantly associated with improved health status (F=3.02, df=4,24, p=.038; U=56.5, p=.043). On the individual scales, the continuation group improved significantly more on the BPRS score after six months of clozapine, even after baseline values were controlled (F= 6.39, df=1,26, p=.018).

Patients who continued clozapine were more likely to be discharged within six months after initiation of the drug than those who discontinued (χ2 =6.44, df=1, p=.01). The median number of days of psychiatric hospital care was 77 for the continuation group. Thirteen of 15 discharged subjects who continued clozapine went to state-funded supervised residential care. Five subjects who continued clozapine started working as volunteers or pursued higher education within the six-month follow-up period.

Costs

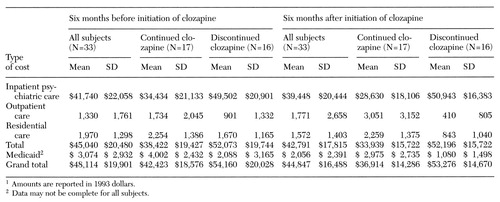

Table 3 summarizes the mean service utilization costs for all subjects and for the continuation and discontinuation groups during the 12-month period. The mean total direct Medicaid costs for all subjects were $92,961 per person—$48,114 per person for the six months preceding clozapine treatment and $44,847 per person for the six months after—for a total of more than $3 million for 33 subjects. The decline in costs per person over the period for the entire sample was not statistically significant.

The group who continued on clozapine incurred lower mean per-person costs during the last six months of the study period, compared with the discontinuation group, even when costs during the prior six months were controlled. These lower mean per-person costs were found regardless of whether costs reflected only inpatient care (F=8.10, df=1,30, p=.008); inpatient, outpatient, and residential care together (F=6.42, df=1,30, p=.017); or all of those types of care plus Medicaid costs (F=6.60, df=1,30, p=.015). The inpatient costs as a percentage of total costs represented 78 percent of all direct costs for the group who continued clozapine, compared with 96 percent of the costs for the discontinuation group. The continuation group incurred additional costs for residential care and outpatient services, compared with the discontinuation group.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that continued clozapine treatment was associated with reduced days of psychiatric hospital care, reduced costs even after including increased costs for outpatient treatment and residential costs, and improved health status for subjects who continued on clozapine for a period as brief as six months. Detailed cost data combined with health status data were obtained for all subjects for the period before and after clozapine initiation, whether the subject continued treatment or not. Thus they complement the findings of randomized clinical trials (10,16) and retrospective chart reviews that have reported the effectiveness of clozapine (6,7,9,17). Systematic differences between the subjects who continue clozapine and those who do not may exist, but we could not definitively identify any differences.

The high rate of discontinuation from clozapine—48 percent—reflects discontinuation of medication while in the hospital for all but one of the 16 subjects who were no longer taking clozapine at six months. This rate is greater than the dropout rates of 35 percent reported in retrospective chart reviews (6,7) but is similar to that observed in clinical trials (10). These differences could be due to sample size, patient population, or the facilities' experience with and support available for treating patients with clozapine, or they could be due to psychiatrists' caution or experience using clozapine (18).

The major limitations of the study include its small sample size, short follow-up period, nonexperimental design, and possible effects of trends in practice during the study period. It is not clear whether our findings from 1993 to 1995 are applicable to treatment practices in 1998. For example, shifting resources, from inpatient to outpatient care, would preclude the relatively long inpatient stays incurred by our subjects.

Conclusions

Clozapine treatment was associated with reduced psychiatric hospital days of care, reduced costs even after including increased costs for outpatient and residential services, and improved health status for subjects who continued on clozapine for six months. The findings are consistent with Michigan's goal of reducing days of psychiatric hospital care and show that clozapine was associated with improved health status for this group of patients.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from the Detroit-Wayne County Community Mental Health Agency.

Dr. Blieden, Dr. Flinders, Dr. Reid, and Dr. Arfken are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences and Dr. Hawkins is with the department of economics at Wayne State University in Detroit. Dr. Hawkins is also with Blue Cross-Blue Shield Michigan in Detroit, and Dr. Reid is also with the Detroit-Wayne County Community Mental Health Agency. At the time of the study Dr. Alphs was with the department of psychiatry at Wayne State University. He currently is with Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation in East Hanover, New Jersey. Address correspondence to Dr. Arfken, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Wayne State University, 9B UHC, 4201 St. Antoine, Detroit, Michigan 48201 (e-mail, [email protected]). An earlier version of this work was presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, held November 9-13, 1997, in Indianapolis.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of publicly supported patients with schizophrenia started on clozapine who did and did not continue the medication for six months

|

Table 2. Mean scores on clinical rating scales at baseline (within one week of initiating clozapine treatment) and six months later of publicly supported patients with schizophrenia who did and did not continue the medication for six months

|

Table 3. Health care costs per person six months before and after initiation of clozapine among publicly supported patients with schizophrenia who did and did not continue the medication for six months1

1. Michigan Critical Health Indicators. Lansing, Michigan Department of Community Health, 1996Google Scholar

2. Health care reform for Americans with severe mental illnesses: report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1448-1465, 1993Google Scholar

3. Rupp A, Keith SJ: The costs of schizophrenia: assessing the burden. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 16:413-422, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Meltzer HY, Cola PA: The pharmacoeconomics of clozapine: a review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55(suppl B):161-165, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fitton A, Benfield P: Clozapine: an appraisal of its pharmacoeconomic benefits in the treatment of schizophrenia. Pharmacoeconomics 4:131-156, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Meltzer HY, Cola PA, Way L, et al: Cost effectiveness of clozapine in neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1630-1638, 1993Link, Google Scholar

7. Revicki DA, Luce BR, Weschler JM, et al: Cost-effectiveness of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:850-854, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Hargreaves WA, Shumway M: Pharmacoeconomics of antipsychotic drug therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 9):66-76, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

9. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC, Cole JO, et al: Hospitalization rates among clozapine-treated patients: a prospective cost-benefit analysis. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 4:247-250, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Weichun X, et al: A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 337:809-815, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Alphs LD, Summerfelt BS, Lann HS, et al: The Negative Symptom Assessment: a new instrument to assess negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 21:159-163, 1989Google Scholar

13. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 6:278-296, 1967Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon ET, Carpenter WT Jr: The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenia deficit syndrome. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10:388-398, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. O'Brien PC: Procedures for comparing samples with multiple endpoints. Biometrics 40:1079-1087, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kane JM, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:789-796, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Reid WH, Mason M, Toprac M: Savings in hospital bed-days related to treatment with clozapine. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:261-264, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Carpenter WT, Conley RR, Buchanan RW, et al: Patient response and resource management: another view of clozapine treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:827-832, 1995Link, Google Scholar