Implementing Publicly Funded Risk Contracts With Community Mental Health Organizations

Abstract

The study analyzed the experience of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health with implementation of new contractual arrangements for services for patients with severe mental illness. The arrangements shifted the financial risk for treatment to community organizations and paid a fixed annual rate per enrolled patient without further adjustment for severity of illness. Patients were assigned to the program based on high prior treatment costs. The new contractual approach enhanced programs' flexibility and accountability and increased their emphasis on principles of psychosocial rehabilitation. Challenges in implementation included disenrollment of the majority of assigned patients by the community organizations at risk for high treatment costs. Prior treatment costs for continuing cases, while high, were lower than those for disenrolled cases. Existing information systems provided limited clinical and cost data, making it difficult to monitor providers' performance. Risk contracting required substantial clinical, fiscal, and management changes at community organizations and the mental health authority. The analysis suggests that mental health authorities that are planning to institute risk contracts need to balance fiscal incentives with performance guarantees and to pay particular attention to information systems requirements and to the severity of patients' illness. Although risk contracts present challenges, they can lead to improvements in service delivery that persist beyond the implementation phase.

Public mental health authorities are increasingly applying managed care technologies to the treatment of individuals with severe and persistent mental illness. These technologies include clinical management mechanisms such as prospective utilization review, organizational structures such as maintenance of a panel of independent providers, and financial arrangements, such as risk contracting. This paper presents a case study of risk contracting with community organizations, a contractual arrangement whereby the community organization assumes some of the risk for the treatment costs of a given population and is responsible for delivering and managing clinical services (1). Capitation is a widely discussed form of risk contract.

Among all managed care arrangements, shifting the risk for treatment costs to providers is undoubtedly the arrangement that clinicians are most concerned about (2,3,4,5). However, relatively few studies have examined the effect of implementing risk contracts for publicly funded mental health care. Policy makers need to understand the challenges they can expect to face during implementation of specific managed care mechanisms, such as risk contracting, so that they can rationally develop interventions to improve mental health services (6).

Although implementation of managed care can substantially reduce treatment costs, concerns have been raised about its potential effect on severely ill populations (7,8,9). However, "managed care" is a term applied loosely to a variety of mechanisms, including gatekeeping, utilization review, and financing, and most reports do not specify exactly which mechanisms or combinations of mechanisms were studied.

These problems aside, experiments in Rochester, New York, and Massachusetts resulted in reduced costs without apparent negative effects on access or quality (10,11), and the Medical Outcomes Study found overall similar outcomes for depressed patients under fee-for-service or prepaid care (12). On the other hand, in the Medical Outcomes Study, more severely depressed patients had worse outcomes under prepaid than under fee-for-service care (13), and in the Hennepin County, Minnesota, experiment, patients with schizophrenia who were treated in HMOs had declines in some outcome measures and the largest contractor withdrew from the project (14). Thus translating managed care approaches from corporate insurance plans, where enrollees typically suffer from depression and anxiety, to the public mental health system, where consumers are often chronically disabled and more severely ill, may present a challenge (15,16,17).

This paper describes challenges encountered during the first year of implementation of the Los Angeles County Partners Program. The Partners Program shifted the financial risk for treatment of severely ill patients to community organizations. Patients were selected based on a history of high treatment costs, and community organizations were paid a fixed annual rate per enrollee without further adjustment for severity of illness. This case study uses qualitative data from direct observation and discussions with key informants and quantitative data on patient characteristics, enrollment, and treatment costs from administrative databases.

The Los Angeles Partners Program

In the fiscal year ending in 1993, the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health oversaw a treatment network that included two state hospitals, two county hospitals, 28 directly operated adult programs, and 410 mental health contracts with 100 community agencies; funding for the network was more than $275 million (18). During this year the county department of mental health served approximately 70,000 individuals. Sixty-three percent were of ethnic minority background: 27 percent were Hispanic, 27 percent were African American, 5 percent were Asian-Pacific Islander, .5 percent were American Indian, and 3.5 percent had other ethnic minority backgrounds.

In the decade leading to the Partners initiative, the county department of mental health experienced repeated budget cuts, resulting in the closing of numerous programs, although the population of Los Angeles County continued to grow. Hospital costs were a particular burden, despite efforts to increase the proportion of care provided in community settings. In 1993 an opportunity emerged for the department of mental health to shift funds from the support of 200 hospital beds to a new, intensive, community-based treatment program for 500 high-cost patients. The county budget process and concerns about political opposition meant that the implementation of the program had to proceed quickly, with limited time for planning and little opportunity to clinically assess patients before enrollment.

Community organizations submitted proposals in response to the county's announcement of this project. Six private, not-for-profit organizations were selected, each of which was to provide care to either 50 or 100 selected patients. All but one of these organizations had previous contracts with the county department of mental health to provide community care to individuals with severe mental illness.

The selected organizations were paid on a per-patient basis, at rates of between $14,000 and $21,000 per patient per year, depending on their original application bid. Although the majority of this payment was fixed, a proportion of the per-patient amount (less than 25 percent overall) was contingent on revenue from Medicaid. The community organizations continued, therefore, to bill for Medicaid-eligible community-based services, such as mental health care and rehabilitation.

These new programs were called integrated service agencies, because they agreed to facilitate, directly provide, or contract for mental health care, housing, social and vocational rehabilitation, medical care, and dental care. Available services were to include 24-hour crisis response, transportation, substance abuse treatment, and active family participation. All services were to be provided within a model emphasizing patient choice and empowerment. The integrated service agencies were to be held financially responsible for treatment across all institutional, crisis, and outpatient settings operated or contracted for by the county department of mental health, with the exception of pharmaceuticals and acute hospitalizations paid for by fee-for-service Medicaid. Any revenue in excess of expenses was to be reinvested in the treatment program.

The first patients were enrolled in June 1993. They were chosen using computerized administrative records maintained by the county department of mental health. The enrollees were restricted to a pool of individuals between 18 and 64 years old who had received treatment from the county department of mental health for at least three of the past five years and who had been high utilizers of county fiscal resources. To be selected, a patient needed to have used an average of more than $30,000 worth of services per year over the past five years and be in the top 15 percent of all utilizers of mental health funds.

The costs used to determine a patient's eligibility for participation in the Partners Program were computed from billing rates for services provided at facilities operated or contracted for by the department of mental health, including outpatient facilities, chronic care hospitals, and acute care hospitals. Cost data were not yet available for the year before program implementation, so assignment was based on services used between 1987 and 1992. Unlike the patients enrolled in some other managed care experiments, the enrollees in the Partners Program could not be clinically screened before assignment because the existing management information system had insufficient clinical data, and funding was not available for in-person assessment.

This selection approach resulted in a pool of 2,576 eligible individuals. These individuals were stratified into three "cost bands" based on their utilization of services during the most recent year for which data were available. Patients were identified as "very high cost" if utilization over that year was equal to or greater than $50,000, "high cost" if utilization was between $30,000 and $50,000, and "moderate cost" if utilization was less than $30,000.

Each integrated service agency was assigned an equivalent proportion of patients from each of the three cost bands. No other contractual provision was made to protect the agencies from expenses that might result from a small number of very expensive patients. The agencies could, however, refuse to accept responsibility for treating patients who met certain criteria, including a history of hospitalization of more than 300 days per year for the past four years, an IQ below 65, or a history of repeated dangerous behavior.

Patients' enrollment in the integrated service agencies was voluntary. If a patient refused to be enrolled or met disenrollment criteria, an agency could petition to have the individual disenrolled. A panel reviewed each request for disenrollment using clinical information provided by the agency and administrative records. The county department of mental health did not have the resources to investigate many disenrollments in great detail; however, the panel made the best use possible of available information to ensure a fair enrollment process. Disenrolled patients returned to the usual treatment services provided by the county department of mental health.

It is noteworthy that the Partners Program targeted patients who had a history of being exceedingly expensive to treat, usually because of repeated or prolonged use of hospital or crisis services. These individuals represent less than 1 percent of all patients who received services from the county department of mental health, and they may constitute a very different population from that found in other programs. For instance, the states of Massachusetts and Iowa have contracted with private vendors to manage care for most or all Medicaid recipients. These populations would be expected to be more diverse, including many people with moderately severe or acute mental disabilities, and capitation of these populations may produce different results.

Experience of the Partners Program

The eligibility criteria resulted in a pool of patients with a history of treatment costs that in some instances exceeded $100,000 per year. Because of limitations in available data, there was little systematic information about why patients had been so difficult to treat or what obstacles would be encountered by the integrated service agencies in attempting to reduce treatment costs.

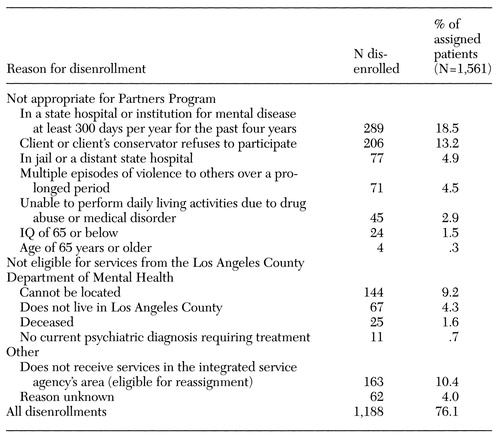

After patients started to be assigned to the integrated service agencies, agency staff learned that some individuals would be quite difficult to move to lower levels of care. Some patients had long histories of hospitalization and extremely difficult clinical situations, such as treatment-refractory schizophrenia with concurrent brittle diabetes or uncontrollable violence. Agencies were allowed to disenroll patients for the reasons shown in Table 1. As patients were disenrolled, replacement patients were selected from the same cost band as the disenrolled patient to minimize financial incentives for disenrollment.

It quickly became apparent that the integrated service agencies were disenrolling many more patients than had been anticipated. Over the first year of the implementation, 1,188 of 1,561 assigned patients were disenrolled. As Table 1 shows, 716 patients were disenrolled because they were not appropriate for the Partners Program; the most frequent reasons for disenrollment were prolonged hospitalization or the patient's refusal to participate. An additional 247 were disenrolled because they were not eligible for services provided by the county department of mental health; the most frequent reason was that they could not be located. Another 163 were disenrolled because they had been assigned to an integrated service agency in the wrong geographic area.

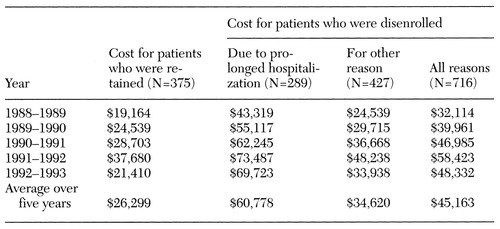

The pool of patients assigned to integrated service agencies had costs during the 1991-1992 fiscal year ranging from $6,095 to $143,472. As shown in Table 2, historical average annual treatment costs for patients retained by the integrated service agencies were highest in 1991-1992 at $37,680 and were substantially lower in 1992-1993, the year before implementation of the Partners Program. Fiscal year 1991-1992 was the most recent one for which cost data were available at start-up, and it is possible that the cost of some clients regressed towards the mean cost between 1992 and assignment to programs in 1993. However, these cost changes are difficult to fully understand, given the small number of research studies that have examined year-by-year costs in populations of patients with severe mental illness (19).

Although the integrated service agencies had a variety of reasons for requesting patient disenrollment, many disenrollments appeared to be due to concerns that the agency would not be able to successfully maintain the patient outside of a hospital or chronic care facility. Being at full financial risk for care at these facilities and facing reimbursement rates that were substantially below prior treatment costs, the agencies had a strong incentive to disenroll high-cost patients.

As shown in Table 2, patients retained by the integrated service agencies had average costs during the year before assignment that were not far above the per-patient contract rates ($21,410), whereas patients disenrolled as inappropriate for the Partners Program had average costs that were substantially higher ($48,332). Not surprisingly, patients disenrolled due to a history of prolonged hospitalization had an average cost that was much higher than that of patients disenrolled for other reasons ($60,778 versus $34,620). The high rate of disenrollment might have been reduced by adjusting the amount paid to integrated service agencies to account for differences in historical cost (risk adjustment) (20) or by sharing the cost of services for high-cost outliers. However, as may be the case with other mental health authorities, the computerized management systems of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health could not produce the data necessary for risk adjustment or cost sharing for Partners patients.

Implementing the Partners Program also led to the identification of political challenges related to the broader network of care for patients with severe mental illness. Existing large mental health systems inevitably have stakeholders who gain from it and who oppose changes. Within the first few months of the Partners project, several systems-level obstacles to implementation emerged. Like problems that developed in the Rochester capitation demonstration (21), they originated less with the Partners Program itself, but rather from the larger network of stakeholders.

For example, one charge of the integrated service agencies was to move patients from more restrictive to less restrictive residential placements. Within the community this often meant moving patients from locked institutions into unlocked residential facilities or private apartments. These locked institutions include state hospitals and privately owned chronic care facilities, referred to in California as institutions for mental disease. The institutions for mental disease and the state hospitals have an incentive not to discharge patients, because unused beds either remain vacant, with loss of revenue, or are filled with more severely ill patients from acute hospitals who are likely to be more expensive to treat.

As integrated service agencies began to plan for discharging patients from locked facilities, it became clear that the locked institutions would actively resist any such effort if this might mean a loss of revenue for them. The institutions for mental disease in Los Angeles County requested, through political channels, that patients be moved out of these facilities if, and only if, replacement patients were offered. Family members and clinicians also expressed concern about whether some patients could be adequately cared for in less restrictive environments.

The department of mental health was able to overcome some of these obstacles through education of patients and families and negotiation with providers. However, this process made it clear that many patients, families, and providers had concerns about changing the patient's treatment, even if the current treatment resulted in frequent hospitalization and the new treatment program offered an enhanced range of services and higher level of individual attention.

Discussion

The design of a managed care contract is critical because it determines provider incentives and the economic efficiency of the program. Particular attention needs to be paid to how incentives to reduce costs and incentives to provide high-quality care are balanced and whether there are opportunities to "game" the system by shifting costs outside the contract.

Contractual issues raised by the Partners implementation include risk sharing and targeting of services to the appropriate population. The Partners Program was a full-risk contract that shifted the responsibility for treatment costs to the community organization. Although full risk creates strong incentives for providers to reduce costs, it also creates strong incentives to avoid responsibility for treating high-cost patients (22). The resulting provider behaviors have been well documented in the economic literature, where they have been referred to as "dumping" (23,24).

Several approaches have been used to attenuate risk and thereby reduce the incentive for dumping. The Health Care Financing Administration's prospective payment system developed methods for identifying outlier patients to reduce the incentive to avoid these patients (25). Similarly, intermediate risk-sharing arrangements exist in which the provider organization is responsible for costs within a given range, but extreme deviations are shared between the purchaser and the provider (26,27). The overall risk of a contract can also be reduced through stop-loss insurance or by creating a "corridor" of risk for the provider, outside of which the purchaser assumes further fiscal responsibility (28). For instance, the provider may be allowed to retain no more than 5 percent of the contract fee if costs are less than expected, or lose no more than 5 percent of the fee if costs exceed expectations.

Risk has also been reduced by combining features of traditional reimbursement with prospective payment (29). Economic theory suggests that optimal contracts between payers and providers should contain features of prospective payment and cost reimbursement when quality or amount of services provided to ill patients cannot be perfectly monitored (30,31,32). Intermediate arrangements used in private-sector employer contracts include cost reimbursement with performance guarantees and financial penalties if the managed care organization fails to achieve the targets. Performance guarantees can include service-quality targets, although there is uncertainty about the best methods for measuring quality of care for patients with severe mental illness (33,34,35).

To be successful, risk contracts should ensure that treatment of the target population is feasible within the terms of the contract and that incentives to selectively enroll lower-cost patients or disenroll higher-cost patients are counterbalanced by other contractual features. In the Partners Program, annual historical mental health treatment cost per patient ranged from about $6,000 to more than $100,000. In contrast to large insurance companies that manage risk over hundreds of thousands of people, the integrated service agencies were not large enough to ensure that extremely high-cost patients would be balanced with low-cost patients. Also, the capitation rate was set substantially below historical costs, requiring large cost reductions to avoid deficits. The agencies therefore had strong incentives to avoid extremely expensive patients.

Several mechanisms exist for decreasing selective enrollment, including varying the reimbursement rate according to the expected cost of treatment based on measures of severity of illness (20,36). It is also possible to adjust reimbursement rates according to past service use, perceived health status, and level of disability, although the ability to predict future mental health costs from existing case-mix adjustments is limited (37).

The potential for selective enrollment and disenrollment becomes especially problematic when mental health authorities assign patients to provider organizations through their administrative data files rather than through clinical screening. When patients are assigned administratively, the provider organization knows more than the mental health authority about the patients' severity of illness and appropriateness for the program, and it becomes difficult to detect when providers avoid higher-cost patients or preferentially select lower-cost ones. This state of "information asymmetry" may be reduced if a payer panel or board reviews the clinical status of each potential enrollee before selection (38).

The high rate of disenrollment during this implementation can also be understood as a response to the clinical status of the patients. The patients selected for this program constituted an extraordinarily ill population with high rates of comorbid disorders and behavioral problems and historically poor compliance with traditional services. Most of the integrated service agencies had successfully delivered publicly funded clinical services to a diverse array of patients. However, they had limited experience with the profoundly ill individuals encountered in the Partners Program and may not have anticipated the dramatic changes in service delivery that can be required to work with this population (39). In addition to using exclusion criteria to shape treatment populations, mental health authorities may wish to facilitate retention of severely ill patients by increasing training and organizational consultation to their contractors.

For a public mental health agency that covers the costs of disenrolled patients, risk contracts that allow selective enrollment can actually increase the agency's overall costs. A good example is the experience of Medicare and health maintenance organizations (HMOs). The capitation rate for HMO patients was set slightly below the mean Medicare cost, but because the HMO programs enrolled patients who were significantly less costly, this form of risk contracting in combination with biased selection has actually increased total Medicare expenditures (40,41).

Conclusions

Risk contracting provided the opportunity for the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health to implement new clinical programs with enhanced accountability and flexibility and an increased emphasis on psychosocial rehabilitation principles. Integrated service agencies successfully enrolled 500 high-cost patients, and none of the agencies withdrew from the project. It is quite possible that the treatment provided by these agencies was more efficient and cost-effective than usual services. However, the Partners Program also demonstrated that the implementation phase of risk contracts can be very challenging and that contract design can have a substantial effect on program efficiency.

Some adaptation of private-sector managed care interventions will be necessary for populations of patients with serious mental illness, yet many fundamental economic principles apply directly and may not be widely known. Unfortunately, in many cases implementation of public-sector managed care is proceeding without unbiased, meaningful evaluation. In Partners, however, policy makers in the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health encouraged independent evaluation efforts, and thereby acquired information that they can use to improve service delivery.

Mental health authorities that implement managed care programs need to be aware of the incentives of stakeholders and work to establish the stakeholders' "buy-in" before program implementation. Also, to continue advocating for their patients, authorities should prepare to assume a far greater role in monitoring care than ever before. As they shift their role from provider to contractor and "watchdog," new skills and tools will be needed. In particular, authorities may need to spend substantially more on performance monitoring and management information systems that provide current, accurate, and detailed fiscal and clinical data. Despite these challenges, new approaches to organizing and financing public mental health care offer great promise.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Ernst Van Loben Sels Charitable Foundation, the Zellerbach Family Fund, a Young Investigator award to Dr. Young from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, and grant P50 MH-54623 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the UCLA-Rand Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders. The authors thank Areta Crowell, Ph.D., R. W. Burgoyne, M.D., Eydie Dominguez, Janet Abreu, and Ron Florendo. The opinions expressed are the authors'.

Dr. Young and Dr. Sullivan are consultants, Dr. Sturm is a behavioral scientist, and Dr. Koegel is a senior behavioral scientist with the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica, California. Dr. Young is also assistant clinical professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Sullivan is also associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. Mr. Murata is chief of the planning and mental health management information systems divisions of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health. Address correspondence to Dr. Young, UCLA Health Services Research Center, 10920 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 300, Los Angeles, California 90024. This paper is one of several in this issue on mental health services research conducted by new investigators.

|

Table 1. Reasons for disenrollment of patients from integrated service agencies during the first year of the Partners Program

|

Table 2. Average annual treatment cost per patient during the five years before assignment to an integrated service agency

1. Frank RG, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP: Risk contracts in managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):50-64, 1995Google Scholar

2. Relman AS: Dealing with conflicts of interest. New England Journal of Medicine 313:749-751, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Relman AS: Salaried physicians and economic incentives. New England Journal of Medicine 319:784, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Financial incentives to limit care: implications for HMOs and IPAs, in Code of Medical Ethics: Report of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs of the American Medical Association. Chicago, American Medical Association, 1990Google Scholar

5. American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs: Ethical issues in managed care. JAMA 273:330-335, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Essock SM, Goldman HH: States' embrace of managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):34-44, 1995Google Scholar

7. Mechanic D, Schlesinger M, McAlpine DD: Management of mental health and substance abuse services: state of the art and early results. Milbank Quarterly 73:19-55, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Miller RH, Luft HS: Does managed care lead to better or worse quality of care? Health Affairs 16(5):7-25, 1997Google Scholar

9. Chang CF, Kiser LJ, Bailey JE, et al: Tennessee's failed managed care program for mental health and substance abuse services. JAMA 279:864-869, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cole RE, Reed SK, Babigian HM, et al: A mental health capitation program: I. patient outcomes. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1090-1096, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Callahan JJ, Shepard DS, Beinecke RH, et al: Mental health/substance abuse treatment in managed care: the Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Health Affairs 14(3):173-184, 1995Google Scholar

12. Wells KB, Sturm R, Sherbourne CD, et al: Caring for Depression. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

13. Rogers WH, Wells KB, Meredith LS, et al: Outcomes for adult outpatients with depression under prepaid or fee-for-service financing. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:517-525, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Lurie N, Moscovice IS, Finch M, et al: Does capitation affect the health of the chronically mentally ill? Results from a randomized trial. JAMA 267:3300-3304, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hogan MF: Managing the whole system of care. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 72:13-24, 1996Google Scholar

16. Cuffel BJ, Snowden L, Masland M, et al: Managed care in the public mental health system. Community Mental Health Journal 32:109-124, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Wagner EH: Managed care and chronic illness: health services research needs. Health Services Research 32:702-714, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

18. Annual Report to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, 1993Google Scholar

19. Frank RG, McGuire TG, Bae JP, et al: Solutions for adverse selection in behavioral health care. Health Care Financing Review 18:109-122, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

20. Sharfstein SS: Prospective cost allocations for the chronic schizophrenic patient. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:395-400, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Babigian HM, Marshall PE: Rochester: a comprehensive capitation experiment. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 43:43-54, 1989Google Scholar

22. Mechanic D: Mental health services in the context of health insurance reform. Milbank Quarterly 71:349-364, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Ansell DA, Schiff RL: Patient dumping: status, implications, and policy recommendations. JAMA 257:1500-1502, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Schlesinger M, Dorwart R, Hoover C, et al: The determinants of dumping: a national study of economically motivated transfers involving mental health care. Health Services Research 32:561-590, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

25. Keeler EB, Carter GM, Trude S: Insurance aspects of DRG outlier payments. Journal of Health Economics 7:193-214, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Sturm R: How does risk sharing between employers and managed behavioral health organizations affect mental health care? Working Paper 113. Los Angeles, Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders, 1997Google Scholar

27. Ma CA, McGuire TG: Costs and incentives in a behavioral health carve-out. Health Affairs 17(2):53-69, 1998Google Scholar

28. Frank RG, Huskamp HA, McGuire TG, et al: Some economics of mental health "carve-outs." Archives of General Psychiatry 53:933-937, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Newhouse JP, Buntin MB, Chapman JD: Risk adjustment and Medicare: taking a closer look. Health Affairs 16(5):26-43, 1997Google Scholar

30. Ellis RP, McGuire TG: Provider behavior under prospective reimbursement: cost sharing and supply. Journal of Health Economics 5:129-151, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Ellis RP, McGuire TG: Optimal payment systems for health services. Journal of Health Economics 9:375-396, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Ma CA: Health care payment systems: cost and quality incentives. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 3:93-112, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Bachman SS: Monitoring mental health service contracts: six states' experiences. Psychiatric Services 47:837-841, 1996Link, Google Scholar

34. Salzer MS, Nixon CT, Schut LJA, et al: Validating quality indicators: quality as relationship between structure, process, and outcome. Evaluation Review 21:292-309, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Young AS, Sullivan G, Burnam MA, et al: Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:611-617, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Scheffler R, Grogan C, Cuffel B, et al: A specialized mental health plan for persons with severe mental illness under managed competition. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:937-942, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

37. Taube C, Lee ES, Forthofer RN: DRGs in psychiatry: an empirical evaluation. Medical Care 22:597-610, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Hargreaves WA: A capitation model for providing mental health services in California. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:275-279, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

39. Essock SM, Kontos N: Implementing assertive community treatment teams. Psychiatric Services 46:679-683, 1995Link, Google Scholar

40. Leibowitz A, Buchanan JL, Mann J: A randomized trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a Medicaid HMO. Journal of Health Economics 11:235-257, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Morgan RO, Virnig BA, DeVito CA, et al: The Medicare-HMO revolving door: the healthy go in and the sick go out. New England Journal of Medicine 337:169-175, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar