Training to Enhance Partnerships Between Mental Health Professionals and Family Caregivers: A Comparative Study

Abstract

A training program for mental health staff was collaboratively developed and delivered by family caregivers and professionals. It addressed calls for less blaming attitudes toward families and increased contact between professionals and families. Two levels of training were compared. Twenty-seven staff members completed a 30-hour extended 12-week program. Eighty-two percent of all eligible staff from area teams attended a brief program involving three or six hours of training. Self-ratings of competence and attitudes toward families improved only for staff receiving extended training. Contacts with families increased for those in the extended program but not for all types of teams, suggesting that length of training and service type may limit the impact of training.

Effective partnerships between professionals and family caregivers emphasizing shared knowledge and perspectives may assist mentally ill persons (1,2). Unhelpful attitudes of mental health practitioners toward families have been seen as barriers to development of such partnerships (3). The few research studies that have attempted to directly measure attitudes show that a majority of staff endorse family involvement in treatment. However, a minority of staff hold explicitly negative views, and the general level of staff contact with families is limited (4,5).

Reports of inservice training programs for mental health staff targeting attitudes and mutual understanding are scarce (6,7). Our project aimed at developing a training program for mental health professionals in Australia that would deepen their understanding of families of mentally ill persons, challenge family-blaming attitudes, and assist them to further involve families in the care and treatment of their relative. This evaluation report focuses on the impact of brief versus extended exposure to training on staff attitudes and level of family contact.

Methods

The project was initiated in 1993 by the Schizophrenia Fellowship of Victoria, a family caregiver organization that collaborated with a family services provider and a large public psychiatric service. The public psychiatric service agreed to implement the training in 1994.

Our strategy emphasized participation of family caregivers and used organizational change principles to address impediments to dissemination of training (8) and maximize lasting impact (9,,10). These principles included working with an area mental health system rather than with single agencies, participation of senior management, consultation with potential participants during development of the training, and design of a training schedule to enable all staff to participate in key workshops. Late in the planning process, the training was opened to family caregivers who were trained support workers and, like the professionals, had a responsibility to assist families.

Twelve weekly three-hour sessions were conducted, with two levels of participation. An extended training group comprising six family caregivers and 23 multidisciplinary staff from an acute ward, two community mental health centers (CMHCs), a mobile treatment team, a crisis team, and a disability support service enrolled for all sessions. Two of the original 29 members of the extended training group were unable to complete the course.

All area staff were encouraged to attend the first and final sessions, and they formed the comparison group of participants in brief training. Of 99 staff members who were eligible to participate in the brief training, 81 (82 percent) attended at least one session.

A family advocacy educator and a mental health professional acted jointly as facilitators for the sessions. Presenters included caregivers and professionals. A systemic understanding of staff-family-patient relationships was encouraged, and topics included understanding blame, practical family engagement, and challenges faced by both families and staff, such as loss of hope. Facilitated discussions highlighted beliefs and attitudes. In "practice research" activities, participants planned actions to try with families or to propose to their agency between training sessions. The facilitators promoted an expectation of mutual discovery, and nonblaming friendly relationships between staff and the family members attending the groups became evident.

The training was evaluated through a pretest-posttest-follow-up design augmented with qualitative feedback. Using pretraining and posttraining questionnaires, staff rated their own skills, knowledge, and experience in working with families. The rating scale for items ranged from 1 to 4, with higher ratings indicating greater skills, knowledge, and experience. An attitude scale with 30 items, the Opinions About Family Work Scale, was devised, using statements by Bernheim and Switalski (4). The rating scale for each item ranged from 1 to 5, with higher mean ratings indicating more positive attitudes to family caregivers. The scale was administered pre- and posttraining to all participants. Data about number of contacts with family and clients were collected from staff before training, after training, and at six-month follow-up.

Results

The extended training course was rated positively by 21 of 25 respondents, with four giving a neutral rating. Paired t tests showed that participants' ratings of their skill, knowledge, and experience with families were significantly higher after training. For skill, the pretraining rating was 2.38±.62, compared with 2.88± .62 after training (t=3.16, df=15, p= .006). For knowledge, the pretraining rating was 2.38±.50, compared with 2.94±.57 after training (t=4.39, df= 15, p=.001). For experience, the pre- and posttraining ratings were 2.38± .50 and 2.88±.62 (t=3.87, df=15, p= .002). The self-ratings of staff members who participated in the brief training showed no significant changes.

Before training, the mean scores of professionals on pro-family attitudes as measured by the Opinions About Family Work Scale did not differ between the brief and extended training groups. However, family members in extended training had a significantly higher mean score than the mean for professionals (4.06±.22 versus 3.34± .37; t=5.05, df=66, p<.001). After training, the mean score on pro-family attitudes for the professionals in brief training did not change. However, the mean score for professionals in extended training increased significantly after training, from 3.43±.48 to 3.70±.49 (paired t=3.33, df=16, p= .004). The posttraining mean score of professionals was not significantly different from the posttraining mean score of family members (3.95±.45).

The impact of the project on family contacts by the CMHC workers, mobile team, and crisis team was investigated by examining pooled data for all staff. (The other facilities participating in the project did not document comparable data on contacts in their recording systems.) Compliance with recording of contacts was 71 percent before training, 71 percent after training, and 55 percent at six-month follow-up.

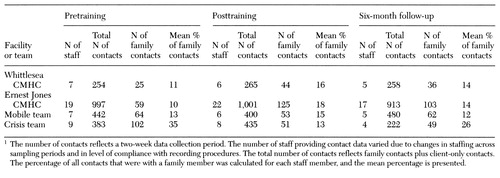

From patient and family contact records, the percentage of total contacts of staff members with family caregivers was calculated. This approach controlled for differences in the total volume of work between the three recording periods. As shown in Table 1, for workers at both the Whittlesea and the Ernest Jones CMHCs, the percentage of family contacts increased from pre- to posttraining; the percentage decreased at follow-up, although not to pretraining levels. The mobile team had little change in the percentage of family contacts.

The percentage of family contacts by the crisis team fell after training from a very high pretraining level; the percentage increased to a relatively high level at follow-up. Crisis staff stated that they experience wide variations in the proportion of clients in contact with families, and that the posttraining recording period was particularly busy. (Our data show that for the crisis team, total contacts per staff member with both families and clients increased by 23 percent from pre- to posttraining. For this reason, data for the crisis team were not analyzed further.)

One-way analyses of variance were performed on the percentage of family contacts across the pretraining, posttraining, and follow-up recording periods. A significant change was noted in the percentage of family contacts for CMHC participants in the extended training (F=4.14, df=2,17, p=.034). A post hoc Newman-Keuls test identified a significant increase from pretraining to posttraining (8 percent to 27 percent). The increase in the percentage of family contacts for the CMHC participants in brief training from pretraining to posttraining to follow-up was not significant (11 percent, 15 percent, and 13 percent, respectively.) The change in the percentage of family contacts for the mobile team staff as a whole was not significant.

Qualitative evaluation via written and videotaped feedback from training participants revealed enthusiastic optimism for collaborative work. Some services reported improvements in service provision; for example, a family visitors room was established in the inpatient ward, and another service reported increased referrals to family support services. Other reports suggested a change in perspective; for example, one participant described "seeing our clients as part of a family unit." Changes in family responses included gifts of "flowers and chocolates" to staff.

Discussion and conclusions

This study was limited by the small size of some teams and changes in personnel over time, with lower compliance in recording contact data during the follow-up period. However, the results suggest the extent of involvement in training that may be required for significant change. Attitude change was evident only with extended training. Significant increases in the percentage of family contacts were found among the CMHC workers who participated in extended training, while only trends of increased family contacts were noted among staff who received the brief training. Brief training involving one or two workshops may be insufficient to achieve measurable behavioral and attitude change.

Contact data suggest that the training may have been most relevant to CMHC workers, although the qualitative data highlighted changes on the inpatient ward. The more specialized work of the crisis and mobile services and their higher percentage of family contacts before training may mean that training that targets family issues for workers in these services is required. The posttraining drop in family contacts for the crisis team was in a period of greater workload, suggesting that work with families suffers when staff members are busier.

We partly attribute the positive outcomes of this project to collaboration between caregivers and professionals at all levels in the areas of planning, training, and group facilitation. Whether the dual role of our family caregiver participants as support workers for families as well as caregivers themselves was an important factor is not clear. Staff are not necessarily accepting of trainers who are family caregivers (7). In our project, inclusion of family caregivers as participants as well as trainers may have usefully changed the relationship dynamics. The shared role of working with families certainly helped staff and family caregiver participants learn together. We suggest that our attention to process issues and emphasis on shared learning led to respect and partnership.

Training to help mental health professionals work more collaboratively with family caregivers can be successfully implemented through genuine partnerships between family members and professionals in the areas of planning, teaching, and participation. However, attitude changes and improvements in level of service may require more than brief training.

Acknowledgments

Both the training program and the evaluation were supported by grants to the Schizophrenia Fellowship of Victoria from the mental health branch of the Department of Human Services, Victoria, Australia.

Mr. Farhall is consultant clinical psychologist with the North Western Health Care Network in Melbourne, Australia, and senior lecturer in the School of Psychological Science at La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria, Australia 3083 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Webster is a research associate in the School of Psychological Science. Ms. Hocking is executive director of SANE Australia in Melbourne. Dr. Leggatt is senior research fellow at Deakin University in Melbourne and president of the World Schizophrenia Fellowship in Toronto. Dr. Riess is director and Mr. Young is a clinical psychologist at Bouverie Centre at La Trobe University. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual Mental Health Services Conference of Australia and New Zealand, held September 5-7, 1995, in Auckland, New Zealand.

|

Table 1. Percentage of contacts with families among staff at two community mental health centers (CMHCs), a mobile team, and a crisis team who received training in working with clients' families1

1. Hatfield AB: Help-seeking behavior in families of schizophrenics. American Journal of Community Psychology 7:563-569, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Solomon P: Families' views of service delivery: an empirical assessment, in Helping Families Cope With Mental Illness. Edited by Lefley H, Wasow M. New York, Gordon & Breach, 1994Google Scholar

3. Holden DF, Lewine RRJ: How families evaluate mental health professionals, resources, and effects of illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:626-633, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Bernheim KF, Switalski T: Mental health staff and patients' relatives: how they view each other. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:63-68, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Castaneda D, Sommer R: Mental health professionals' attitudes toward the family's role in care of the mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1195-1197, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Bernheim KF, Olewniczak JR: Sensitizing mental hygiene therapy aides to the needs of patients' relatives. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1013-1015, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Zipple A, Spaniol L, Rogers ES: Training mental health practitioners to assist families of persons who have a psychiatric disability. Rehabilitation Psychology 35:121-129, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Kavanagh DJ, Clark D, Piatowska O, et al: Application of cognitive-behavioural family intervention for schizophrenia in multidisciplinary teams: what can the matter be? Australian Psychologist 28:181-188, 1993Google Scholar

9. Corrigan PW, McCracken SG: Refocusing the training of psychiatric rehabilitation staff. Psychiatric Services 46:1172-1177, 1995Link, Google Scholar

10. Curry L, Farhall J: The shift from psychiatric nurse to manager: the design, implementation, and evaluation of an action learning program. Therapeutic Communities 16:215-228, 1995Google Scholar