Mental Disorders of Eskimos Seen at a Community Mental Health Center in Western Alaska

Abstract

The charts of 343 Eskimos seen at a community mental health center in northwestern Alaska were reviewed, and data on demographic characteristics, DSM-III-R diagnoses, and history of suicide attempts were collected. Substance use disorders were the most common group of mental disorders. Substance use patterns differed substantially according to age and gender. Both children and adults had high rates of attempted suicide (66 percent and 67 percent). Rates of bipolar disorder and eating disorders were substantially lower than those seen in mental health clinics serving the general U.S. population. .

Rapid sociocultural changes in Native American communities are reflected in the nature and extent of mental health problems in these populations (1). Several community surveys have reported high rates of psychiatric disorders. Using structured diagnostic interviews, Kinzie and associates (2) found that 69 percent of the adult population in an American Indian village had a definite or probable mental disorder, compared with 32 percent in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study of the general U.S. population (3). Rates of addictive diseases and depression are especially high (2,4,5). For example, lifetime prevalence rates of alcohol dependence or abuse within selected American Indian communities range from 27 to 51 percent (2,6).

Most epidemiological surveys in Native American populations have used problem checklists or questionnaires to measure psychopathology (4,5). Some have used structured diagnostic interviews to classify American Indian subjects using a modern diagnostic system (2,6), but sample sizes have been small and such studies have not been performed in Eskimo populations.

During his clinical work at the regional community mental health center in Nome, Alaska, one of the authors (RJG) noted a low rate of bipolar disorder (manic-depressive illness) and eating disorders among Eskimo patients attending the clinic. This observation, along with the lack of studies measuring rates among Eskimos of psychopathology according to our current diagnostic classification system, prompted the study described in this paper. We report the rates of psychiatric disorders among Eskimos attending a community mental health center in Western Alaska and offer possible explanations for these findings.

Methods

The Eskimos in the Bering Straits region of Alaska are members of four distinct ethnic groups: Inuit, Inupiat, Yupik, and Siberian Yupik. Although the people retain much of their traditional values and life style, almost all are literate in English.

Any person in the region is eligible to receive services at the community mental health center (CMHC) in Nome. Many patients are referred by their local medical provider.

The study population includes all Eskimo patients evaluated by the staff psychiatrist (RG) at the CMHC between October 1990 and April 1993. Charts were reviewed retrospectively, and data on demographic characteristics, DSM-III-R diagnoses, and history of suicide attempts were collected. Between-group differences were analyzed using two-tailed chi square tests with Yates correction.

Results

Over the two years of the study, 343 Eskimo patients—88 children and adolescents between the ages of six and 17 years and 255 adults age 18 and older—were evaluated. Among the children and adolescents there was a slight preponderance of females (N=49). The mean age of the children and adolescents was 14±2.3 years. The mean age of the adult patients was 37±15 years.

Most youths had problems with substance use disorders (N=49), but females most frequently used alcohol, and males surprisingly were more likely to have problems with inhalants. Eating disorders were infrequent (N=3).

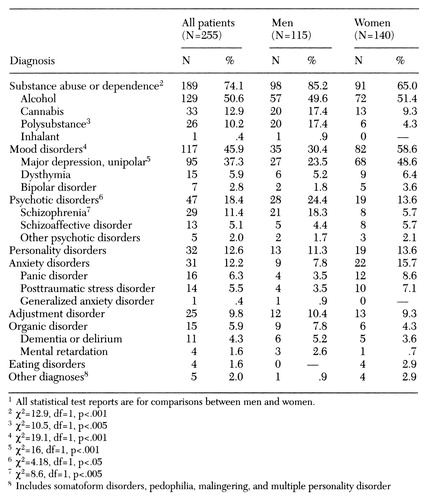

Table 1 outlines the distribution of diagnoses among the adult patients. Substance use disorders were prevalent, especially among men. Whereas inhalant use was much less frequent among adults compared with children, alcohol and cannabis use were much more frequent.

Most surprising was the low frequency of bipolar disorder (manic-depressive illness) and eating disorders. One would expect that approximately equal numbers of patients would have bipolar disorder as would have schizophrenia in a mental health clinic (7), but less than 3 percent of these Eskimo patients received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Sixty-six percent of the children and 67 percent of the adults reported a previous suicide attempt. An interesting finding was that the two age groups differed in the gender distribution of the suicide attempters (χ2= 11.6, df=1, p<.001), with females reporting higher rates among youths and adult men and women reporting approximately equal rates. This difference suggests that suicide may have different etiologies in different age groups.

Discussion and conclusions

Perhaps our most striking finding is the high prevalence of substance use disorders in both children and adults attending the mental health clinic. The substances of choice appeared to be alcohol, cannabis, and inhalants, and preference varied by age and by gender. Although striking, the finding was not unexpected, as high rates of substance use have been noted in surveys fairly consistently across Native American ethnic groups (8). Reasons for these consistent findings are unknown, but may include biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors (2,4).

Of concern was a 67 percent rate of reported suicide attempts. This rate compares with rates of 4 to 25 percent reported in other mental health clinics (7). Suicide rates vary widely among Native American tribes and subgroups (8). Acculturation and high rates of alcoholism have been the most common explanations given for Native American suicide (9), but a more recent study in this Eskimo population suggested that early parental loss and limited grieving mechanisms are important factors (10).

This study supported our prediction of low rates of eating disorders and bipolar disorder. In the general U.S. population, an outpatient mental health clinic might expect that approximately 8 percent of its adult patients would have bipolar disorder (7). In contrast, we found a rate of 3 percent in our clinic. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a low rate of bipolar disorder has been reported in a Native American population.

A low rate of eating disorders is easily explained by culturally based differences in attitudes towards body weight and appearance. It is more difficult to explain the low rate of bipolar disorder. One possibility is sampling bias—that is, the expected number of persons with bipolar disorder lived in the community, but they did not come to our clinic. We believe this explanation is unlikely given the disabling nature of the illness and the lack of alternative mental health resources in the region.

Another possible explanation is that our subgroup, or Native Americans as a whole, have low genetic loading for bipolar disorder or a different phenotypic expression of the illness. For example, high rates of cannabis use may have led to a psychotic diathesis of a bipolar predisposition, thereby causing a predominantly psychotic manifestation of bipolar illness. In support of this explanation, we found that cannabis use was highly correlated with assignment of a psychotic disorder (χ2=23.6, df=1, p<.001). In addition, our clinical observation was that many of the patients that were diagnosed with schizophrenia appeared to respond to mood stabilizers.

The limitations of the study include its use of retrospective analysis and assignment of diagnoses based on the clinical evaluations of a single psychiatrist. This study highlights the need for similar studies in other Native American clinic populations, as well as systematic community surveys employing structured diagnostic interviews and a modern diagnostic classification system.

Corrections

The Alcohol & Drug Abuse column by Robert M. Malow and others in the August 1998 issue (pages 1021-1022 and 1024) listed an incorrect name and academic degree for one of the authors. Shvawn McPherson Baker, Pharm.D., is the sevond author of "Adherence to Complex Complex Combination Antiretroviral Therapies by HIV-Positive Drug Abusers."

An editing change distorted the meaning of the second sentence of Philip Candilis' review of The Ethichal Way: Challenges and Solutions for Managed Behavioral Healthcare by H. Steven Moffic, M.D., in the August 1998 book review section (page 1101). The sentence should have read "The discussion of how to rein in costs and yet maintain good patient care has entered the fiction rack."

Dr. Aoun is a fellow in child psychiatry in the division of child and adolescent psychiatry of the department of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota Hospital and Clinics in Minneapolis. Dr. Gregory is associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the State University of New York Health Science Center, 750 East Adams Street, Syracuse, New York 13210.

|

Table 1. Psychiatric diagnoses of adult Eskimo patients evaluated at a community mental health center in Nome, Alaska1

1. Foulks EF, Katz S: The mental health of Alaskan Natives. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 49:91-96, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kinzie DJ, Leung PK, Boehnlein J, et al: Psychiatric epidemiology of an Indian village: a 19-year replication study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:33-39, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Tischler GL, et al: Affective disorders in five United States communities. Psychological Medicine 18:141-153, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Zebrowski PL, Gregory RJ: Inhalant use patterns among Eskimo school children in western Alaska. Journal of Addictive Diseases 15:67-77, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Gregory RJ: Screening for depression in Native Americans. Federal Practitioner 14:38-45, 1997Google Scholar

6. Shore JH, Manson SM, Bloom JD, et al: A pilot study of depression among American Indian patients with Research Diagnostic Criteria. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research 1:4-15, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Asnis GM, Friedman TA, Sanderson WC, et al: Suicidal behaviors in adult psychiatric outpatients: I. description and prevalence. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:108-112, 1993Link, Google Scholar

8. Manson SM, Walker RD, Kivlahan DR: Psychiatric assessment and treatment of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:165-173, 1983Google Scholar

9. Kettl PA, Bixler EO: Suicide in Alaskan Natives. Psychiatry 54:55-63, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gregory RJ: Grief and loss among Eskimos attempting suicide in western Alaska. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1815-1816, 1994Link, Google Scholar