Program Directors' Views of the Effect of Managed Care on Substance Abuse Programs in Los Angeles County

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study sought information about the effect of managed care on substance abuse treatment programs through a survey of program directors. METHODS: Fifty program directors who supervised a total of 134 substance abuse treatment programs in Los Angeles County completed a survey during the period from January to May 1997 on program changes made in response to managed care, major concerns, the advantages and disadvantages of managed care, and plans for further program changes to succeed in the managed care environment. RESULTS: Program directors reported that the most frequent change made in response to managed care was increased outreach and marketing. Their greatest concern in the managed care environment was being forced to provide the least costly service, rather than the best care for patients. Respondents identified an increased focus on outcomes as an advantage of managed care and restrictions on services due to contractual agreements as a disadvantage. Planned program changes addressed the areas of program structure, types of programs offered, staff composition, revenue generation, referral sources, prevention, outcome measures, relationships with other organizations, and accreditation and certification. CONCLUSIONS: Although some substance abuse treatment programs seem to be reducing their scope or preparing to close in response to managed care, others are developing strategies to survive and even thrive in this new economic environment.

Providers of mental health and substance abuse treatment are experiencing a rapid shift from operating as relatively autonomous units to being part of managed care systems. This move is fueled by community and national demand to provide treatment for mental illness and substance abuse to a broader base of clients at lower cost (1).

The transition to managed care is creating turmoil among administrators and providers in treatment programs for alcohol and drug abuse. Utilization review, control of admissions, and shortened lengths of stay have reduced revenue to both private and public treatment programs (2). As a result, some programs may not survive, while others may survive but with major changes, and still others may thrive. The effect of managed care on the survival of treatment centers is a significant concern, as alcohol and drug abuse is estimated to cost U.S. society about $166 billion annually in crime, loss of productivity, and health care and estimated to result in more than 120,000 deaths per year (3). Further, alcohol and drug abuse treatment has been shown to decrease the use of addictive substances as well as increase lifetime productivity and decrease related costs (4). This paper reports the results of a descriptive survey that sought to identify how managed care is affecting substance abuse treatment programs in Los Angeles County and to determine how these programs have responded, or are planning to respond, to these changes.

Background

Managed care is providing an increasing proportion of the treatment of psychiatric and substance abuse disorders (5). However, the impact of managed care structures and processes on substance abuse treatment is not well understood. Many experts have documented the need for research to identify the impact of managed care on access to substance abuse treatment and on the quality and outcomes of that treatment (1,6,7,8).

More information is available on the impact of managed care on the treatment of psychiatric illness. Managed care has reduced the overall cost of mental health care (9). However, clinicians claim that this reduction has been accomplished by denying needed services and that reducing mental health care costs may result in higher medical and surgical expenditures (10).

Within substance abuse treatment, managed care has shifted the emphasis to less expensive formats such as outpatient care and group work and to the use of less costly therapists (1,11,12). A survey of 11 treatment programs found that staff members believe managed care, as presently structured, will result in treatment programs that are less comprehensive, less accessible, and less effective (13).

In contrast, Bartlett (5) asserted that research has demonstrated the effectiveness of partial hospitalization and non-hospital-based treatment—treatment alternatives for which managed care stimulated payment. Other researchers reported a series of studies that found similar outcomes for substance abuse treatment in day treatment programs versus inpatient settings (14). Another study, based on 1,594 patient records, reported that recidivism rates were no higher for patients in managed care programs than for patients in non-managed care arrangements (11).

We could find no studies that reported perceptions of how groups of substance abuse treatment programs are being affected by managed care and could find no indications of how substance abuse treatment programs, as an aggregate, are responding to managed care. The survey described in this paper was undertaken to address these gaps.

Methods

The UCLA Drug Abuse Research Center conducted an extensive study of 247 treatment programs in Los Angeles County, published in 1995 (15). Between January and May 1997, we attempted to contact these programs by mail and phone to ask for their participation in this study. Twenty-five programs had closed or could not be located, and many programs had merged with other programs. A total of 156 organizations were contacted, and 50 program directors, representing 134 different programs, responded. The response rate was approximately 32 percent, but could not be determined exactly because returns were anonymous.

The questionnaire, created specifically for this study, contained 22 items requesting information on the type of program the respondent represented; changes in programs since 1994 as a result of managed care; and major concerns about the influence of managed care on substance abuse programs, as well as advantages and disadvantages of managed care. Respondents were also asked to identify changes planned to increase their ability to succeed clinically and financially. Types of change included those affecting structure, program, sources of referral, staff composition, revenue generation, focus on prevention, focus on outcomes, types of outcomes measured, relationships with other organizations, and legal, accreditation, or certification status. Six items requested information on the demographic characteristics of the program director, such as gender, age, education, professional background, years employed in substance abuse treatment, and years in the present position. Forced-choice options followed each question.

Questionnaire items were drawn from the literature and the suggestions of a panel of ten experts in the field of substance abuse treatment and research. The panel examined the questionnaire to determine face and content validity and the appropriateness of the structure and wording of the items. Feedback from the panel was used for revising the questionnaire. Reliability was assessed by comparing responses to items that measured similar content. Agreement ranged from 76 to 84 percent, showing satisfactory consistency.

Participants were asked to check all appropriate responses from the list of forced-choice options. Most questions asked that respondents indicate the most important response, to provide data that could be clearly quantified. A category for "other," with room for description was included in each major category to collect qualitative data and to encourage respondents to provide all relevant information. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

Results

Respondents supervised 134 different programs, including 30 outpatient programs (22 percent of programs), 16 day treatment programs (12 percent), 14 inpatient programs (10 percent), 12 residential programs (9 percent), 11 drug diversion programs (8 percent), nine recovery homes (7 percent), eight crisis intervention programs (6 percent), and seven inpatient detoxification programs (5 percent). The remaining programs were early intervention, outpatient detoxification, methadone maintenance, residential detoxification, community recovery center, and "other" types of programs.

Fifty-eight percent of the program directors were female. The 50 directors ranged in age from 25 to 65 years, with an average of 48 years. Education ranged from high school to advanced degrees, with 28 directors, or 56 percent, holding master's or doctoral degrees. As for professional background, 11 directors had certification in alcohol and drug counseling (22 percent), nine were chemical dependence professionals without such certification (18 percent), eight had a business background (16 percent), and seven had master's degrees in social work or qualifications as a licensed clinical social worker (14 percent). Nine directors identified themselves as recovering from substance abuse. Other backgrounds included training as a minister, nurse, or physician and degrees or certification in marriage and family counseling. More than half of the respondents (26 respondents, or 52 percent) had worked in substance abuse treatment 11 or more years, but 34 (68 percent) had been in their present position less than ten years. Data on the ethnicity of the program directors were not collected.

This paper reports program directors' responses to questions about changes made in their treatment programs or planned for the future in response to managed care. Directors' responses to questions about their feelings about managed care are also reported. Some qualitative data are reported in the text.

Changes made

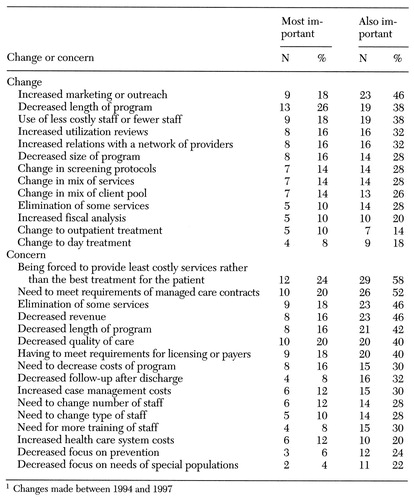

Program directors were asked to identify the most important change in their treatment programs since 1994 as a result of managed care. As Table 1 shows, the most commonly identified changes were increased outreach and marketing, decreased length of the treatment program, reduction in staff or use of less costly staff, increased utilization review, and increased relations with a network of providers.

One respondent commented, "We moved from the private into the public sector." Three believed county-funded programs would not be affected by managed care, and one said managed care required the director to work in an illegal and unethical manner.

Concern about possible impact

Directors were asked to identify their greatest concern about the possible impact of managed care on their programs. As Table 1 shows, the greatest concern most commonly identified by directors was that they would be forced to provide the least costly rather than the best treatment for patients. Others indicated that their greatest concern was meeting the requirements of managed care contracts, elimination of services, decreased revenue, decreased length of the treatment program, and decreased quality.

In their written comments, directors expressed fears of being swallowed up by managed care and of being excluded from managed care contracts or bypassed in the treatment referral process. They also expressed concern about the lack of care for indigent people and undocumented immigrants.

Disadvantages and advantages

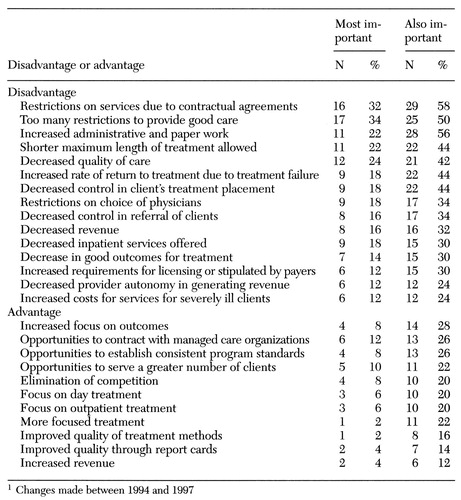

Respondents were most likely to identify the restrictions created by contractual agreements as the greatest disadvantage of managed care. Other factors identified as the greatest disadvantage were the presence of too many restrictions to provide good care, increased administrative work and paper work, and restrictions on the length of treatment. Other respondents identified decreased quality of care, increased rate of return due to treatment failure, and decreased control over client treatment as the greatest disadvantage.

Directors' written comments expressed concern about the lack of support for methadone maintenance, the decrease in community resources due to the closing or downsizing of programs, and general chaos, secondary to "bureaucracy and to discouragement on the part of providers." One director wrote, "Agencies no longer have quality-of-care options. They are system driven, system compliant. A few years ago 'agency variance' was a mark of quality, and funds could be used in creative ways. Now, treatment processes and ancillary services are restricted by budget constraints."

The directors were asked to identify the greatest advantage managed care may create for their treatment program. As Table 2 shows, they identified an increased focus on outcomes, the opportunity to contract with managed care providers, and the establishment of consistent program standards. The opportunity to serve a greater number of clients, elimination of competition, and a focus on day and outpatient treatment were also mentioned.

Plans for responding to managed care

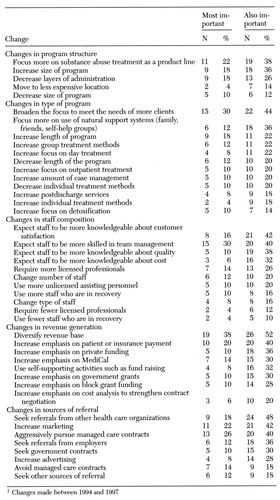

Table 3 shows changes that were planned to increase programs' ability to succeed financially and clinically under managed care.

Changes in structure.

Plans for changes in program structure included focusing on substance abuse treatment as a product line, increasing the size of treatment programs, and decreasing layers of administration.

One respondent commented that structural change would be difficult, indicating that "there are no layers of administration to cut." Another remarked, "We will seek grants, charge a higher fee-for-service, and change the demographics of our client base." One indicated a need to make alliances with medical providers to ensure that clients have "more access to medical care." Another emphasized plans to target the program to particular client groups. One wrote, "We will continue our mission of serving battered women and preventing violence." Another wrote, "We will serve those not served elsewhere."

Changes in type of program.

Directors planned to broaden their program to meet the needs of more clients; to increase or decrease the length of the treatment program; to focus on clients' natural support systems such as family, friends, and self-help groups; and to increase the use of group treatment methods.

Changes in staff composition.

Directors wanted staff to become more skilled in team management, more knowledgeable about customer satisfaction, more focused on quality, and more knowledgeable about cost. Some directors wanted to employ more licensed professionals, and some expected to change the type and number of staff. One director commented that the program staff were excellent and did not plan to make changes, but another said that the program needed more licensed professionals instead of "recovering" peer staff.

Changes in revenue generation.

An emphasis on diversifying the revenue base was indicated by more than half of the directors, and several respondents indicated this activity would be their top priority. Some planned to rely more on private insurance, MediCal, government grants, or block grants. Strategies to secure private funding, contract negotiation, and self-supporting activities were planned by others. Specialization in treatment of dual diagnosis or of heroin and opiate addiction was also identified, and others planned greater financial restrictions or refused to work with government contracts or managed care.

Changes in sources of referral.

Many directors planned to aggressively pursue managed care contracts, to seek referrals from other health care organizations, and to increase marketing activities. Others planned to increase referrals by seeking referrals from employers, pursuing government contracts, or increasing advertising. Some directors said they would avoid managed care contracts altogether.

Comments indicated that referrals would be sought from the entertainment industry, churches, homeless shelters, private methadone programs, other private sources, and family members. One program planned to increase school-based referrals in the community using various fund-raising mechanisms. One director expressed concern that only populations meeting certain criteria would receive services and that many more persons could die as a result of substance abuse.

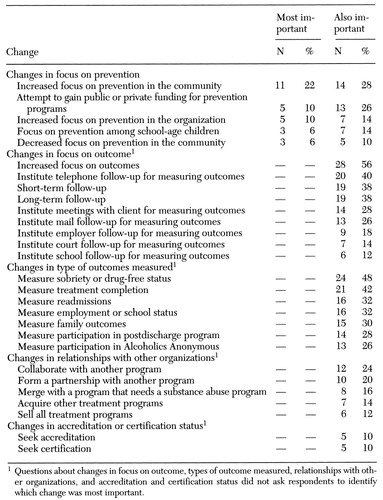

Additional changes

Table 4 shows additional changes planned in response to managed care.

Changes in the focus on prevention.

Some program directors indicated that their program would focus on prevention within the program or in the community. Others planned to obtain funding for prevention, including prevention activities among school-age children. Comments were diverse, expressing both support of prevention activities and skepticism about their value.

Changes in focus and type of outcomes.

Several directors planned to increase their focus on outcomes through short-term or long-term follow-up. Strategies for follow-up by telephone or mail and through meetings with clients were planned, as were procedures for obtaining data on outcomes through clients' employers or schools and the court system. Planned outcome measures included measures of clients' drug-free status, treatment completion, readmission, and employment or school status. Some directors planned to measure clients' family outcomes, participation in a postdischarge program, or participation in Alcoholics Anonymous. Some treatment programs targeted for veterans planned to use the Addiction Severity Index to measure outcome. Another program planned to use a life satisfaction measure and a measure of psychiatric hospital days.

Changes in relationships with other organizations.

Many respondents planned to forge a relationship with an organization that needed substance abuse treatment through collaboration, partnership, or merger. Other directors planned to increase their program's financial viability by acquiring other treatment programs. Six program directors mentioned plans to sell their treatment programs. Twelve respondents wrote comments about partnering with other agencies or organizations, including schools, mental health programs, other health care organizations, inpatient programs, outpatient clinics, residential treatment facilities, hospitals, not-for-profit organizations, a facility needing detoxification services, health maintenance organizations, and methadone treatment programs. Several mentioned the need to offer services covering the continuum of care, and one described a collaborative arrangement among 20 organizations to provide several types of programs, including early intervention, children's care, residential treatment, and dual-diagnosis treatment services. However, another complained of lack of community support due to program closure.

Changes in accreditation or certification status.

Plans included seeking state certification or seeking accreditation by the Commission on the Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities or the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Two respondents mentioned plans for their program to become licensed for methadone treatment or to treat clients referred by the courts. Another planned to be approved by MediCal, and one was scheduled to work with the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) and had to meet that agency's program requirements.

Discussion

The substance abuse treatment programs in Los Angeles County represented in this survey have experienced considerable turmoil in meeting the challenges of managed care, yet most program directors reported planning changes they feel will help their programs persevere in the managed care environment. Many directors expressed a strong commitment to substance abuse treatment and to the clientele they serve, and some expressed fears about the threat of managed care to the survival of the addicted individual. A few felt managed care would not affect their organization, or that its effects could be avoided, but the vast majority were attuned to changes that have occurred and are likely to occur in the future.

Frustrations about managed care centered on the challenge of trying to provide good care in the face of increased restrictions and requirements. Although few respondents would admit to a decreased quality of care, some expressed concern about treatment failure, poor outcomes, and decreased control of quality. Most directors expressed concerns about the impact of managed care on their programs.

Although many respondents expressed negative feelings about managed care, several respondents reported strategies for living with it, or even capitalizing on it. Directors planned changes to decrease costs and increase their program's ability to contract with managed care organizations. They planned to provide substance abuse treatment as a product line, to offer more services over the continuum of care, and to serve the needs of more types of clients. Decreasing layers of administration, increasing group treatment methods, using family and community support systems, and focusing on day treatment, outpatient care, and case management were all identified as strategies to improve care while minimizing costs.

Increasing the referral and revenue base was an important priority for many respondents. Their plans included increasing marketing and advertising, seeking managed care contracts, attracting referrals from other health care providers and employers, and seeking government contracts. Some indicated they were already part of a network of providers, and others planned to pursue more network relationships.

Although respondents less often identified advantages of managed care, they did mention the value of an increased focus on outcomes. Program directors also viewed managed care as an opportunity to establish consistent program standards, to expand services, to serve more clients, and to eliminate competition.

Survey respondents indicated that substance abuse treatment programs are clearly in the throes of network building with complementary organizations. Partnering, merging, acquiring, buying, and selling were all actions planned for the future. Another strategy was to expand the program's legal or certification status to be able to increase the diversity of clientele and revenue sources. However, some programs planned to downsize, close, or change from providing substance abuse treatment services to providing some other type of service.

Substance abuse programs have clearly been affected by the customer-oriented focus of the 1990s. Directors wanted staff members to be more knowledgeable about customer satisfaction, team management, quality, and costs—the same factors that are driving other industries (16) and other health care organizations. The directors anticipated needing more, rather than fewer, licensed personnel because of the additional regulatory requirements associated with managed care.

Conclusions

Data from this survey suggest the variation in treatment programs' reactions to the drastic changes caused by managed care. Although the study results have limited generalizability due to the nature of the sample, the findings may help in planning for the spread of managed care throughout the country. Some substance abuse treatment programs appeared to be withdrawing and preparing for closure, while others were strategizing about ways to survive, and even thrive, in the new economic environment. Many of these programs in Los Angeles County probably have the resourcefulness to survive the changes created by managed care, but little is known about the influence of the changes these programs are making to survive. As one program director said, as substance abuse treatment becomes more system driven, "variability disappears, homogeneity occurs, and redundancy is eliminated." Will managed care eliminate excellent programs, as well as weak programs, or will it result in higher standards and better outcomes overall?

Multiple studies have shown the financial, personal, and societal value of substance abuse treatment. More research is needed to examine substance abuse treatment outcomes under managed care, both in the aggregate to influence policy and at the individual program level to evaluate the quality of treatment.

First-Person Accounts Invited for Column

Patients, former patients, family members, and mental health professionals are invited to submit first-person accounts of experiences with mental illness and treatment for the Personal Accounts column of Psychiatric Services.Maximum length is 1,600 words. The column appears every other month.

Material to be considered for publication should be sent to the column editor, Jeffrey L. Geller, M.D., M.P.H., at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester, Massachusetts 01655. Authors may publish under a pseudonym if they wish.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly funded by grants from the UCLA School of Nursing and the UCLA Faculty Senate. The author thanks Wayne Sugita, Lydia Becerra, Yih-Ing Hser, Ph.D., Christine Grella, Ph.D., Margaret Polinsky, Ph.D., Richard Rawson, Ph.D., Beverly Quaye, R.N., M.N., Brenda Kuhn, R.N., Ph.D., Anne Dechairo, R.N., M.S., Elaine Alvarez, Ph.D., Rosario Pineda-Miller, M.S.N., Nga Vuu, Mary Crook, M.S.N., Lynn Brecht, Ph.D., and Adeline Nyamathi, Ph.D.

Dr. McNeese-Smith is assistant professor and coordinator of the nursing administration graduate program in the School of Nursing at the University of California, Los Angeles, Box 956917, 700 Tiverton Avenue, Los Angeles, California 90095 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Changes made in response to managed care and concerns about managed care identified as most important and also important by 50 directors of substance abuse treatment programs in Los Angeles County1

|

Table 2. Disadvantages and advantages of managed care identified as most important and also important by 50 directors of substance abuse treatment programs in Los Angeles County1

|

Table 3. Program changes planned in response to managed care identified as most important and also important by 50 directors of substance abuse treatment programs in Los Angeles County1

|

Table 4. Clinical and administrative changes planned in response to managed care identified as important by 50 directors of substance abuse treatment programs in Los Angeles County

1. Mechanic D, Schlesinger M, McAlpine D: Management of mental health and substance abuse services: state of the art and early results. Milbank Quarterly 73:19-55, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Iglehart J: Health policy report: managed care and mental health. New England Journal of Medicine 334:131-135, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rouse B (ed): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Statistics Sourcebook. Tiburon, Calif, CentraLink, 1997Google Scholar

4. Mueller M, Wyman J: Study sheds new light on the state of drug abuse treatment nationwide. NIDA (National Institiute on Drug Abuse) Notes 12(5):1,4-8, 1997Google Scholar

5. Bartlett J: The emergence of managed care and its impact on psychiatry. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 63:25-34, 1994Google Scholar

6. Dorwart R: Managed mental health care: myths and realities in the 1990s. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1087-1091, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Tarlov A, Ware J, Greenfield S, et al: The Medical Outcomes Study: an application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. JAMA 262:928-943, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Wells K, Astrachan B, Tischler G, et al: Issues and approaches in evaluating managed mental health care. Milbank Quarterly 73:57-75, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Olsen D, Rickles J, Travlik K: A treatment-team model of managed mental health care. Psychiatric Services 46:252-256, 1995Link, Google Scholar

10. Fuller M: More is less: increasing access as a strategy for managing health care costs. Psychiatric Services 46:1015-1017, 1995Link, Google Scholar

11. Renz E, Chung R, Fillman T, et al: The effect of managed care on the treatment outcome of substance use disorders. General Hospital Psychiatry 17:287-292, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Thompson J, Burns B, Goldman H, et al: Initial level of care and clinical status in a managed mental health program. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:599-603, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

13. French M, Dunlap L, Galinis D, et al: Health care reforms and managed care for substance abuse services: findings from eleven case studies. Journal of Public Health Policy 17:181-203, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Schneider R, Herbert M: Substance abuse day treatment and managed health care. Journal of Mental Health Administration 19:119-124, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Polinsky M, Hser Y, Anglin D, et al: Drug treatment programs in Los Angeles County. Los Angeles, UCLA Drug Abuse Research Center, 1995Google Scholar

16. Hellriegel D, Slocum J: Management, 7th ed. Cincinnati, South-Western College Publishing, 1996Google Scholar