Public Expenditures Related to the Criminal Justice System and to Services for Arrestees With a Serious Mental Illness

A recent estimate suggests that nearly one million people with serious mental illnesses are arrested each year ( 1 ). Many are arrested for minor offenses ( 2 ). When these individuals return from prison or jail, many communities are unprepared to offer needed treatment and other services, which often results in their return to the criminal justice system ( 3 ). This movement in and out of the criminal justice, health, and social service systems generates significant and recurring expenditures. Although several studies have estimated the criminal justice components of these expenditures, few have attempted to capture total expenditures ( 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ).

Our purpose was to identify as many of these expenditures as possible using a variety of state and local administrative data sets and to examine whether aggregate expenditures vary among demographic and diagnostic subgroups.

Methods

This research was conducted with all necessary approvals from the institutional review board of the University of South Florida. The Pinellas County Criminal Justice Information System (CJIS) was used to identify all individuals under age 65 who were arrested and spent time in the Pinellas County jail system from July 1, 2003, to June 30, 2004. For purposes of analysis it was assumed that each arrest resulted in at least one day in jail, because all arrestees are booked at the Pinellas County Jail.

The CJIS system does not include diagnostic information. Therefore, to identify which arrestees had a diagnosis of serious mental illness, the arrestee data file was matched against several Pinellas county and statewide data sets that contain an assigned diagnosis. The data sets included the Florida Medicaid claims files, the service event data set maintained by the Florida State Mental Health and Substance Abuse Authority, and three additional county-specific data sets (health and social services, homeless, and emergency medical services). Diagnoses used as indicators of serious mental illness included four that were combined for analysis into a single category of psychotic disorder diagnoses—schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorders, and other psychotic disorders—bipolar I disorder, and major depressive or other bipolar and mood disorders. Link-King probabilistic-deterministic linking and unduplication software ( www.the-link-king.com ) was used to match the arrestee data set with the data set containing diagnoses. A total of 3,769 participants with a serious mental illness were identified through this method, representing 10.1% of all arrestees for the 12-month period.

The CJIS and Florida Department of Law Enforcement data systems were then used to identify all arrests and jail days experienced by these individuals in Pinellas County during the 12 months preceding the year used to identify the arrestee pool (July 1, 2002, to June 30, 2003) and the 24 months after (July 1, 2004, to June 10, 2006). The Florida Department of Corrections information system was used to identify all individuals in the sample who entered the state prison system at any time during the four-year study period along with the associated dates and durations of prison stays. Average expenditures per day in the Pinellas County jail system and in the Florida Department of Corrections prison system were used to calculate the criminal justice expenditures for each participant. State Medicaid claims and managed care encounter data, State Mental Health and Substance Abuse Authority service data, and model costs were used to estimate general medical and mental health expenditures. Expenditures associated with specific services funded by Pinellas County were used to estimate local health and social services expenditures made on behalf of study participants during the four-year period.

Independent variables included age (coded as 20 years or younger, 21–39, 40–50, and 51–64), sex, race-ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, and other nonwhite), mental health diagnosis (coded as described above), number of felonies and misdemeanors, homelessness (yes or no), involuntary psychiatric hospitalization (yes or no), diagnosis of a substance use disorder (yes or no), and number of mental health contacts, defined as emergency room and inpatient combined and outpatient. Because the variables measuring mental health contacts were skewed, we stratified each variable into three categories: the frequency of emergency room and inpatient mental health contacts was measured as none (N=1,481, 39% of the sample), one to three (N=1,261, 34%), or more than three (N=1,027, 27%), and the frequency of outpatient mental health contacts was measured as none (N=1,356, 36%), one to 12 (N=1,178, 31%), or more than 12 (N=1,235, 33%).

Participants had resided in Pinellas County for a mean±SD of 3.44±.76 of the four years of the study. In all, 2,225 participants (59%) were in residence for all four years. Because not all participants were in Pinellas County for the entire period, criminal justice and mental health services were recorded longitudinally across 16 90-day time periods or quarters. If a person was recorded as having a Pinellas County contact in one of four quarters in a given year, the person was considered for analysis for all four quarters of the year. On the basis of this method, participants averaged 13.8±3.1 quarters of eligibility. The results were adjusted for the number of eligible quarters and the total number of months in the community per individual. The outcome (aggregate expenditures) included expenditures associated with mental health and social services, general medical services, jail and prison stays, emergency room services, inpatient services, outpatient services, pharmacy, and emergency medical services.

Multiple regression adjusting for all study variables was used. Because the outcome variable was highly skewed, which influenced the results, log-transformed expenditures were used in the final analyses. In addition to estimating results for the entire sample, we separately considered those enrolled in Medicaid at least at some point during the study (N=1,138, 30%) and those not enrolled (N=2,631, 30%). Of the possible 16 quarters, Medicaid-enrolled participants were enrolled in Medicaid for a mean of 7.2±4.7 quarters.

Results

The mean age of the 3,769 participants was 36±10 years; 243 (6%) were 20 years of age or younger, 1,962 (52%) were between 21 and 39 years, 1,245 (33%) were between 40 and 50 years, and 319 (9%) were between 51 and 64 years. The sample included 2,277 (59%) men, and 2,808 participants (75%) were white, 744 (20%) were black, 171 (5%) were Hispanic, and 46 (1%) were from another racial-ethnic group. A total of 1,154 participants (31%) had major depressive disorder, 1,111 (30%) had bipolar I disorder, 813 (22%) had psychotic disorders, and 685 (18%) had other bipolar and mood disorders. A total of 509 (14%) were homeless (measured as a dichotomous variable), 1,645 (44%) had undergone at least one involuntary psychiatric examination under Florida's civil commitment law, 2,521 (67%) had a diagnosis of a substance use disorder, 2,153 (57%) had at least one felony arrest, and 3,233 (86%) had at least one misdemeanor arrest.

Aggregate expenditures for the cohort were $94,957,465 over the four-year period, with a median expenditure per person of $15,134. The mean aggregate expenditures per eligible quarter for the 3,769 individuals were $1,830±$3,732 (median=$365). Overall, 48% of the expenditures were associated with arrests and jail and prison stays, 39% with mental health services, 12% with general medical services, and 1% with social services.

Regression models also were estimated for participants who were enrolled in Medicaid at some point in the four years and those who were not. Among enrollees, the aggregate expenditures were $40,676,232, with a median of $22,037 per person. The mean aggregate expenditures per eligible quarter were $2,447±$4,797 (median=$656). Expenditures associated with arrests, jail stays, and prison stays accounted for 34% of the expenditures, mental health services for 50%, general medical services for 16%, and social services for less than 1%. Among those not enrolled in Medicaid, aggregate expenditures were $54,281,233, with a median of $12,776 per person. The mean aggregate expenditures per eligible quarter were $1,539±$3,063 (median=$248). Overall, 59% of the expenditures were associated with arrests, jail stays, and prison stays; 31% with mental health services; 9% with general medical services; and 1% with social services. As this comparison indicates, the median expenditures for Medicaid-enrolled individuals were nearly $10,000 higher than for those not enrolled ($22,037 versus $12,776), and the percentage of expenditures for criminal justice for Medicaid-enrolled individuals was substantially lower than for those not enrolled (34% versus 59%).

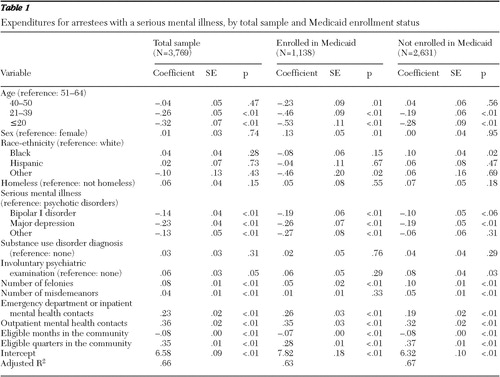

Regression results are presented in Table 1 . Study variables accounted for 66% of the variance in aggregate expenditures for the entire sample, 63% for those enrolled in Medicaid, and 67% for those not enrolled. Aggregate expenditures were similar for those between 51 and 64 and those between 40 and 50 years of age and then were progressively lower in the younger age groups. Psychotic disorders were associated with higher expenditures than diagnoses of bipolar I disorder, major depression, and other bipolar and mood disorders. A substance use disorder diagnosis, at least one involuntary psychiatric examination, and homelessness at any time during the study period were also associated with higher expenditures, as were felony and misdemeanor arrests. Finally, more mental health contacts and eligible quarters were associated with higher expenditures, whereas more months in the community (rather than in jail or prison) were associated with lower expenditures.

|

Variations in expenditures for participants with different characteristics were substantial. For example, the 83 participants over 40 years of age with a psychotic disorder, at least one involuntary psychiatric examination, more than three emergency room or inpatient contacts, and 12 outpatient mental health-related contacts incurred a median expenditure per quarter of $1,543—more than four times the sample median. For this subgroup the distribution of expenditures was quite different from that for the overall cohort, with 72% of the expenditures associated with mental health services, 19% with criminal justice, 8% with general medical services, and 1% with social services. When this group was further restricted to include only those with at least one felony (N=42), median quarterly expenditures increased to $1,782, with 72% associated with mental health, 23% with criminal justice, 4% with general medical, and 1% with social services.

Diagnosis also had a substantial influence on total expenditures. The median quarterly expenditure for those with a psychotic disorder was $2,921, whereas it was $1,752 for those with bipolar I disorder, $1,338 for those with major depression, and $1,419 for those with other diagnoses.

Discussion and conclusions

These data show that individuals with a serious mental illness and criminal justice involvement generated substantial aggregate public expenditures. However, expenditures were concentrated in a relatively small subgroup of arrestees with identifiable characteristics and service utilization patterns. For example, individuals with psychotic disorders who were at least 40 years old, who had experienced an involuntary psychiatric evaluation, and who had more arrests and mental health contacts had significantly higher aggregate expenditures. Patterns were similar when the sample was divided into those who were enrolled in Medicaid at some point during the four years and those who were not. Male gender was significantly associated with higher expenditures only among the Medicaid enrolled. In addition, black race, a history of one or more involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations, and higher arrest rates were more strongly associated with higher expenditures for those enrolled in Medicaid than for those who had never been enrolled.

Individuals enrolled in Medicaid at some point also generated higher expenditures overall than those who were never enrolled in Medicaid. The distribution of expenditures was also different, with a greater proportion of expenditures devoted to mental health services among Medicaid enrollees and to criminal justice services among those who were never enrolled. The finding of higher treatment expenditures among Medicaid enrollees may be attributable to a variety of factors, including the fact that Florida eligibility standards for Medicaid, like those of most states, rely on the definition of disability found in the federal Social Security regulations. That definition requires that the individual have a severe mental or physical condition that has been disabling for at least 12 months. Therefore, those enrolled in Medicaid may have more serious and persistent illnesses than those not enrolled, along with financial eligibility for services.

Overall, among individuals who had the highest total expenditures, the proportion of expenditures was greater for mental health services and less for criminal justice services, compared with their peers who had lower total expenditures. This finding suggests that an important focus for policy makers who want to reduce expenditures associated with this population may be the nature and effectiveness of expenditures on mental health services.

This study had several limitations. For example, court processing costs and police expenditures were not available in calculating criminal justice costs, nor were probation-related costs. Jail pharmacy data were not available, nor were pharmacy data for those not enrolled in Medicaid. Therefore, the reported expenditures represent most but not all publicly funded criminal justice and health expenditures. Second, analyses reflect the amounts paid for health and social services rather than actual direct and indirect costs, which may or may not be different. Third, average expenditures for jail and prison days were used rather than actual costs, which may also have led to underestimates. However, because this study utilized and integrated more administrative data sets than most previous studies and examined expenditures over four years, it is among the most comprehensive reports to date of expenditures incurred over time by arrestees with serious mental illnesses.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by funding from Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, L.L.C.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Morrissey JP, Cuddeback GS, Cuellar AE, et al: The role of Medicaid enrollment and outpatient service use in jail recidivism among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 58:794–801, 2007Google Scholar

2. Lamberti JS: Understanding and preventing criminal recidivism among adults with psychotic disorders. Psychiatric Services 58:773–781, 2007Google Scholar

3. Draine J, Herman DB: Critical time intervention for reentry from prison for persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 58:1577–1581, 2007Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, et al: Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry 165:703–711, 2008Google Scholar

5. Clark RE, Ricketts SK, McHugo GJ: Legal system involvement and costs for persons in treatment for severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 50:641–647, 1999Google Scholar

6. Domino ME, Norton EC, Morrissey JP, et al: Cost shifting to jails after a change to managed mental health care. Health Services Research 39:1379–1401, 2004Google Scholar

7. Wolff N, Helminiak TW, Diamond RJ: Estimated societal costs of assertive community mental health care. Psychiatric Services 46:898–906, 1995Google Scholar