Reasons and Determinants for Not Receiving Treatment for Common Mental Disorders

On a global scale, anxiety and depression are the most common mental disorders. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported a community prevalence of anxiety ranging from 2% (Shanghai) to 18% (United States) and a prevalence of depression ranging from .8% (Nigeria) to 9.6% (United States) ( 1 ). Comparable figures have been replicated in other studies ( 2 , 3 ).

Mental disorders have disabling effects on physical, social, and personal functioning ( 4 , 5 ). The economic costs of minor and major depression are estimated at U.S. $160 and $190 million per million inhabitants, respectively ( 6 ).

Considering the consequences of anxiety and depression, it is remarkable that these mental disorders remain untreated for many persons. According to WHO, treatment rates range from .8% in Nigeria to 15.3% in the United States ( 1 ). Other research has revealed that 26% to 33% of patients receive professional help for their problems in the Netherlands ( 7 , 8 ), Europe ( 8 ), and Australia ( 9 ).

Patients who are more inclined to use health services for their psychiatric problems are middle-aged women and persons who have a relatively high education level, are not or are no longer married, are unemployed, live in an urban area, have comorbid conditions, and have a high level of disability. Furthermore, health care is more often sought by patients who tend to perceive themselves as having a mental problem, and they have a more positive evaluation of their mental health care provider and have greater trust in professional help and greater distrust in lay help ( 3 , 7 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ). However, these studies were primarily concerned with a comparison of treated versus nontreated patients, without considering patients' reasons for not being treated.

The study presented here aimed to contribute to the debate on undertreatment by focusing on the patients' perspective, and it consequently distinguished three groups of patients with an untreated DSM-IV diagnosis: patients who do not perceive having a mental problem, patients who perceive having a mental problem but do not report any need for care, and patients who perceive having a mental problem and express a need for care. These three groups were then compared with patients with a DSM-IV diagnosis who received treatment.

This study focused on reasons for not seeking treatment for anxiety or a depressive disorder. Furthermore, this study examined which sociodemographic characteristics and clinical and functional status measures are related to treatment and to the different reasons for nontreatment.

Methods

Sampling and data collection

All data used in this study were derived from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), which was started in 2004. The rationale, objectives, and methods of NESDA are described in detail elsewhere. The study protocol was approved centrally by the Ethical Review Board of the VU University Medical Centre, and subsequently by local review boards of each participating center ( 14 ).

Respondents were recruited from 65 general practitioners, using a three-stage procedure. First, a random selection of 23,750 patients aged 18–65 years who consulted their general practitioner in the past four months, regardless of the reason for their visit, were sent a Kessler-10 screening questionnaire ( 15 ) to measure psychological distress along with five additional questions on anxiety. A total of 10,706 screens were returned (45%). Persons who screened positive were screened by telephone with a short form of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) ( 16 ). Respondents with a probable diagnosis of anxiety or depression who were fluent in Dutch and agreed to take part in NESDA were included. Written informed consent was obtained after the procedure had been fully explained. Baseline assessment included a full CIDI interview, conducted by specifically trained research staff. Only respondents with a six-month anxiety disorder or affective disorder were selected for this study (N=743).

Measurements

Classification of reason for no treatment. Four patient groups were formed: untreated patients who did not perceive having a mental problem, untreated patients who perceived having a mental problem but did not report any need for care, untreated patients who perceived having a mental problem and expressed a need for care, and treated patients.

This classification was created by the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ) ( 17 ). The PNCQ is a fully structured interview that assesses the patient's perception of the presence of a mental problem, the perceived need for care, and the patient's utilization of health care services—that is, whether the patient consulted a general practitioner, specialist, occupational physician, social worker, psychologist, psychiatrist, psychotherapist, or mental health institution for a mental problem. Patients who confirmed contact with at least one health care provider were considered to be "treated." Patients who did not were considered to be "untreated." Treatment refers to care received from the health care providers mentioned above, because only professional care was assessed in this study.

Patients' self-reported perceived need for care from a professional was assessed for each of five types of care: information (about mental illness, its treatments, or available services), medication, counseling (psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or counseling), practical support (help with housing or money problems, to improve the ability to work, or to use time in other ways), and skills training (help to improve the ability to look after oneself or one's home or help to meet people for support and company). For this study, referral to a mental health care specialist was added. Respondents who perceived an unmet need for care were presented with a series of possible reasons for not seeking treatment and were asked which reason applied to their situation.

Small adaptations were made to the original PNCQ to make it applicable to the Dutch health care system.

Determinants. In keeping with the study of Verhaak and colleagues ( 13 ), three kinds of determinants for help-seeking behavior, based on Andersen's behavioral model ( 18 , 19 ), were distinguished: predisposing factors, factors that enable the use of services, and factors that determine the need for care.

Predisposing factors. During the baseline assessment, information was gathered concerning sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, gender, education level, country of birth, marital status, and household composition. Social support was addressed by one item assessing the size of the respondent's social network. The Loneliness Scale ( 20 ) measures the amount of loneliness a respondent experiences by citing 11 statements, such as "I often feel rejected."

Enabling factors. The perceived accessibility of health services was measured on a 4-point Likert scale by the item "I was able to make an appointment within two days," from the QUOTE instrument (QUality Of care Through the Eyes of the patient), which addresses the evaluation of care received for depression and anxiety ( 21 ). The income level and employment status of the respondent were ascertained during the interview.

Clinical need factors. Symptom severity was assessed by the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS) ( 22 ) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) ( 23 ). Furthermore, we also used the WHO Disability Assessment Scale II (WHODAS-II) ( 24 ), which addresses functional disability. Comorbidity was defined as having more than one anxiety or depressive disorder. To create an index of somatic health, an inventory was constructed to assess the number of chronic somatic diseases for which medical treatment was received.

Statistical analysis

First, we analyzed the reasons patients reported for not receiving treatment, resulting in the three categories mentioned above. Second, we compared these three groups of patients and the treated patients on their predisposing characteristics and enabling and need factors, using chi square analyses for categorical variables and one-way analyses of variance followed by Bonferroni tests for continuous variables. All continuous variables were normally distributed. A multinomial logistic regression model was used to determine which of the previously mentioned characteristics predicted the four treatment categories when all significant variables were considered simultaneously, using respondents who received treatment as a reference group. However, because the symptom severity (BAI and IDS) and disability (WHODAS-II) measures showed very strong intercorrelations, only the disability measure was added. The BAI and IDS address the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively, and thus relate to a specific disorder, whereas the WHODAS-II measures general disability. All analyses were carried out with SPSS, version 14.0.

Results

Characteristics of the study sample

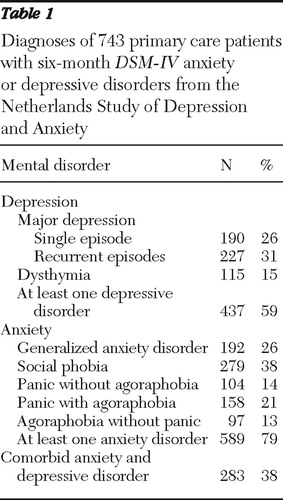

The sample consisted of 525 women (71%). Respondents were on average 44.9±12.1 years old (range 18 to 65 years). Participants received on average 11.8±3.4 years of education, and 652 (88%) were native Dutch. The vast majority of patients had an anxiety disorder (N=589, 79%), 437 (59%) had depression, and 283 (38%) had both depression and anxiety. Table 1 lists respondents' diagnoses.

|

Reasons for not seeking treatment

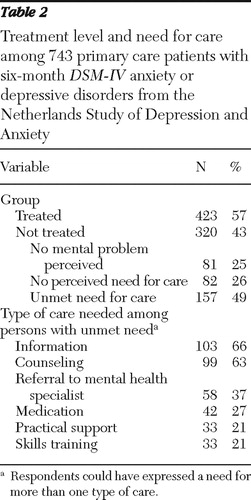

Table 2 shows the number of respondents with an anxiety or depressive disorder in each of the four groups and the types of care needed among those with unmet needs. More than half (57%) of the respondents received treatment, whereas 43% did not receive professional help for a mental disorder. Of these nontreated patients, 25% did not perceive having a mental problem and 26% perceived a mental problem but did not express any need for care. The remaining 49% of nontreated respondents expressed a need for care but did not receive treatment. Among persons with unmet need, information and counseling was most needed, followed by a need for referral to a mental health specialist. Twenty-two percent (N=34) of these respondents perceived a need for only information, practical support, or skills training, which are forms of care that may be considered as nontraditional (data not shown).

|

Patients with a perceived need for care were asked about their reasons for not seeking treatment. The results are shown in Table 3 . For all forms of care, preferring to manage the problem themselves was the main reason reported. Between 21% and 36% of untreated patients believed information, medication, referral, and counseling would not be effective in their case. Respondents in need of practical support and skills training frequently reported not knowing where to find it.

|

Differences between the four groups

Table 4 compares patients from the four groups on predisposing characteristics, enabling factors, and clinical need factors.

|

Bonferroni tests showed that patients born in a country other than the Netherlands were more likely to perceive an unmet need for care than untreated patients without a need for care or treated patients (p<.05). Patients who did not perceive having any mental problem were healthier than other untreated and treated patient groups: they reported less severe symptoms of anxiety and depression, experienced fewer functional restrictions, and were less likely to have a comorbid disorder (p<.05). Patients who perceived having a mental problem but expressed no need for care reported slightly more severe symptoms of anxiety and depression than patients who perceived no mental problem (p<.05). Treated patients and untreated patients with a perceived need for care had the severest consequences of a mental disorder: they reported more severe symptoms of anxiety and depression and experienced more functional disability than the other two untreated patient groups (p<.001). However, there were no significant differences in clinical need factors between these two groups of patients. Treated patients and untreated patients with a perceived need for care reported less social support than patients who perceived themselves as mentally healthy (p<.05). Notably, patients with an unmet need for care experienced the most loneliness, compared with the other three groups (p=.01).

Additionally, a multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed, using treated patients as a reference group. The results are shown in Table 5 . When the analysis controlled for all other significant variables, disability was a significant predictor of treatment status (p<.05): patients who reported many restrictions in daily functioning were more likely to receive care. Additionally, compared with those who received treatment, those with an unmet need for care were more likely to be born outside the Netherlands and to experience loneliness (p<.05).

|

Discussion

The results of the study presented here show that 43% of primary care patients with an anxiety or depressive disorder were not treated. Of these nontreated patients, 25% perceived themselves as mentally healthy, another 26% had no perceived need for any type of care, and 49% perceived a need for care which was not met.

Two main reasons were found for not receiving care among patients who perceived a need: First, most patients preferred to manage their problem themselves. Care providers can still promote mental health among patients with this viewpoint by promoting patient empowerment, so that patients can ultimately deal with their problems themselves. Second, respondents considered commonly used interventions not effective in their case. Although it may sound strange that patients would perceive that they need a form of help that they do not find effective, this viewpoint is likely an expression of general feelings of pessimism or cynicism. A relatively small portion of patients did not receive treatment because of barriers such as being afraid to ask for help or asking but not receiving help. Only a few patients indicated not receiving care because they could not afford it. The results point to a number of predisposing and need factors in determining the reasons for not receiving treatment. Specifically, both the treated patients and untreated patients who expressed a need for care suffered the severest consequences of anxiety and depression: compared with patients without a perceived need for care, they reported more severe symptoms of their disorders, greater disability, more loneliness, and less social support.

Main findings

Our finding that nearly half of the respondents with a mental disorder did not receive treatment is in accordance with the literature ( 12 , 25 ). Also, we found that 22% of patients with an anxiety or depressive disorder did not perceive a need for care, which is supported by previous studies. Prins and colleagues ( 26 ) concluded in a literature review that estimates of unperceived need range between 16% and 51%. Considering the relatively mild symptoms of these patients, they are probably right to try to solve their problems themselves.

Unique to this study is the fact that for each type of care, untreated patients with a perceived need were questioned about their reasons for not using a particular kind of service. It is interesting that a considerable number of respondents expressed a perceived lack of effectiveness for commonly used types of treatment, which can be understood by examining other studies: Priest and colleagues ( 27 ) found that only 46% of lay people believed antidepressants to be effective. Jorm and colleagues ( 28 ) verified that the helpfulness of a psychiatrist, psychologist, or psychotherapist, as well as of antidepressants, was substantially more negatively rated by the public than by health professionals. Also, studies demonstrated that the public has fragile trust in mental health care workers ( 12 , 29 ).

Few studies have compared the characteristics of treated and nontreated patients; the additional subdivision of patients by perception of having a mental disorder and perceived need for care in this study is relatively new. Our finding that a greater clinical need was associated with a higher probability of having a perceived need for care is in line with previous research ( 1 , 3 , 30 , 31 ). Also, it confirms the association between clinical status and perceived need, as mentioned by Codony and colleagues ( 32 ). Our findings imply that most patients make an adequate estimation of their need for care: untreated patients without a self-perceived need had relatively mild symptoms of anxiety and depression and were probably capable of solving their problem themselves. Those in need of care suffered from more severe consequences and could benefit from treatment. Yet the most interesting findings of this study are related to the identification of a worrisome group of patients—namely, those who perceived a need for care and experienced serious consequences of anxiety and depression but did not receive treatment.

Compared with treated patients, those with an unmet need for care were more likely to be born outside the Netherlands. Persons from ethnic minority groups in the Netherlands face migrant-specific barriers to health care consumption caused by cultural stigmas associated with mental health problems and their treatment and by insufficient knowledge of Dutch society and its health care system ( 33 ). Furthermore, these patients experienced more loneliness than those who received treatment. The association between loneliness and depression has been noted before ( 34 , 35 , 36 ). Recently, a longitudinal study of middle-aged and older adults showed a causal relationship: loneliness predicted depressive symptoms in subsequent years, independent of depressive symptoms and psychosocial factors at baseline ( 37 ). Our findings indicate that loneliness is also associated with an unmet need for care among patients with an anxiety or depressive disorder.

Strengths and weaknesses

An important strength of this study consists in the comprehensive measurement of perceived need for different types of treatment for a mental disorder by the use of the PNCQ ( 17 ). However, we do acknowledge the study's limitations. First, data on professional health care utilization was assessed by using self-report measures. Although this is the most common procedure in health care research, there is some evidence showing that patients with depression overreport their health care utilization, probably because of recall bias ( 38 ). Second, our study was cross-sectional, which means that causal relations between the predictors and different reasons for nontreatment could not be determined. Also, diagnoses were established by research staff with the CIDI. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that a research definition of an anxiety and depressive disorder was used, instead of a clinical definition.

A final limitation concerns the generalizability of our findings. Because respondents were recruited from the vicinity of three large cities, people from these highly urbanized regions were overrepresented in our sample. Furthermore, two patient groups were underrepresented in the NESDA study: patients who rarely or never visited their general practitioner and therefore could not be approached to take part in this study during the four months of recruitment and patients who were not fluent in Dutch. Because NESDA used a convenience sample of primary care patients and because being fluent in Dutch was an inclusion criterion, patients who were born in the Netherlands were overrepresented. In addition, findings were based on patients' experiences with the Dutch health care system. It is important for future research to confirm whether our results can be replicated in other countries.

Clinical implications

The most common reasons for patients not to receive treatment for their psychiatric problems included patients' preference to manage the problem themselves and a perceived lack of effectiveness of commonly used types of treatment. Research among general practitioners who reported reasons for depressed patients' failure to receive guideline-concordant care showed that physicians attribute 76% of the barriers to patient-centered factors, including psychosocial circumstances and patient attitudes and beliefs about depression and depression treatment ( 39 ). However, it is important to recognize that the reported explanations for not initiating treatment are not entirely patient centered. For instance, care providers make a substantial contribution to patients' attitudes and beliefs about anxiety and depression treatment. This implies that interventions for improving undertreatment of patients with a mental disorder should be aimed at both the care provider and the patient.

Furthermore, when considering care that is truly patient centered, it is important to differentiate between individual patients who have different reasons for not seeking treatment. For instance, more than half of the patients who perceived a need for care indicated a preference for managing the problem themselves. A way of meeting this preference is by implementing patient empowerment among patients with a mental problem. Empowerment is defined by Gibson ( 40 ) as "a social process of recognizing, promoting, and enhancing people's abilities to meet their own needs, solve their own problems, and mobilize the necessary resources in order to feel in control of their own lives." This concept of empowerment is already being used in care of patients with diabetes ( 41 ) and rheumatoid arthritis ( 42 ). Emerging studies determining the effectiveness of self-help treatment for mental disorders, such as bibliotherapy, in which the patient works more or less independently through a standardized treatment in book form or on a computer, and Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (with or without professional support), have shown promising results ( 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ).

Patients who perceive a lack of effectiveness in commonly used types of treatment could benefit from better information. To support patients in making an informed decision on treatment, it is important that information provided by mental health care workers should address not only the success but also the sometimes limited effectiveness of some types of treatment. For instance, a study among antidepressant users who received an educational flyer that included information about depression and its treatment has demonstrated that informed patients sought additional help from a psychotherapist more often than uninformed patients ( 47 ).

Conclusions

The results from our study point to a group of people at risk of not receiving treatment even though they perceive a need for care. Primary care physicians should pay considerable attention to patients with a mental disorder who were born in a foreign country, report loneliness, receive little social support, and experience substantial clinical impairment. They are at risk of not receiving treatment, although they could benefit from it.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant 20076240 from Fund Psychische Gezondheid (mental health fund). The infrastructure for the NESDA (Nederlandse Studie naar Depressie en Angst) study ( www.nesda.nl ) is funded through the Geestkracht program of the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw, grant number 10-000-1002) and is supported by participating universities and mental health care organizations: VU University Medical Center, GGZ inGeest, Arkin, Leiden University Medical Center, GGZ Rivierduinen, University Medical Center Groningen, Lentis, GGZ Friesland, GGZ Drenthe, Scientific Institute for Quality of Healthcare (IQ Healthcare), Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL), and Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction (Trimbos).

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al: Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291:2581– 2590, 2004Google Scholar

2. Bijl RV, van Zessen G, Ravelli A: Psychiatric morbidity among adults in the Netherlands: the NEMESIS-Study. II: prevalence of psychiatric disorders: Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study [in Dutch]. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde 141:2453–2460, 1997Google Scholar

3. Hamalainen J, Isometsa E, Sihvo S, et al: Use of health services for major depressive and anxiety disorders in Finland. Depression and Anxiety 25:27–37, 2008Google Scholar

4. Ormel J, Petukhova M, Chatterji S, et al: Disability and treatment of specific mental and physical disorders across the world. British Journal of Psychiatry 192:368–375, 2008Google Scholar

5. Wittchen HU, Kessler RC, Beesdo K, et al: Generalized anxiety and depression in primary care: prevalence, recognition, and management. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63(suppl 8):24–34, 2002Google Scholar

6. Cuijpers P, Smit F, Oostenbrink J, et al: Economic costs of minor depression: a population-based study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 115:229–236, 2007Google Scholar

7. Bijl RV, Ravelli A: Psychiatric morbidity, service use, and need for care in the general population: results of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. American Journal of Public Health 90:602–607, 2000Google Scholar

8. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al: Use of mental health services in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplementum 47–54, 2004Google Scholar

9. Andrews G, Issakidis C, Carter G: Shortfall in mental health service utilisation. British Journal of Psychiatry 179:417–425, 2001Google Scholar

10. Lepine JP, Gastpar M, Mendlewicz J, et al: Depression in the community: the first pan-European study DEPRES (Depression Research in European Society). International Clinical Psychopharmacology 12:19–29, 1997Google Scholar

11. Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Hiripi E, et al: The prevalence of treated and untreated mental disorders in five countries. Health Affairs 22(3):122–133, 2003Google Scholar

12. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, et al: The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research 36:987–1007, 2001Google Scholar

13. Verhaak PFM, Prins MA, Spreeuwenberg P, et al: Receiving treatment for common mental disorders. General Hospital Psychiatry 31:46–55, 2008Google Scholar

14. Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Smit JH, et al: The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): rationale, objectives and methods. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 17:121– 140, 2008Google Scholar

15. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al: Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:184–189, 2003Google Scholar

16. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Geneva, World Health Organization, 1990Google Scholar

17. Meadows G, Harvey C, Fossey E, et al: Assessing perceived need for mental health care in a community survey: development of the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:427–435, 2000Google Scholar

18. Andersen R, Newman J: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 51:95–124, 1973Google Scholar

19. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model on access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

20. Jong-Gierveld J, Kamphuis F: The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Applied Psychological Measurement 9:289– 299, 1985Google Scholar

21. Sixma HJ, Kerssens JJ, Campen CV, et al: Quality of care from the patients' perspective: from theoretical concept to a new measuring instrument. Health Expectations 1:82–95, 1998Google Scholar

22. Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, et al: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine 26:477–486, 1996Google Scholar

23. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al: An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 56:893–897, 1988Google Scholar

24. Chwastiak LA, Von Korff M: Disability in depression and back pain: evaluation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS II) in a primary care setting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 56:507–514, 2003Google Scholar

25. Andrews G, Sanderson K, Slade T, et al: Why does the burden of disease persist? Relating the burden of anxiety and depression to effectiveness of treatment. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78:446– 454, 2000Google Scholar

26. Prins MA, Verhaak PF, Bensing JM, et al: Health beliefs and perceived need for mental health care of anxiety and depression—the patients' perspective explored. Clinical Psychology Review 28:1038–1058, 2008Google Scholar

27. Priest RG, Vize C, Roberts A, et al: Lay people's attitudes to treatment of depression: results of opinion poll for Defeat Depression Campaign just before its launch. British Medical Journal 313:858–859, 1996Google Scholar

28. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, et al: Helpfulness of interventions for mental disorders: beliefs of health professionals compared with the general public. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:233–237, 1997Google Scholar

29. Van Weert CMC, Bongers IMB, Van de Goort LAM, et al: Trust in the Dutch health care services [in Dutch]. Tijdschrift voor Gezondheidswetenschappen 84:238– 240, 2006Google Scholar

30. Meadows G, Burgess P, Bobevski I, et al: Perceived need for mental health care: influences of diagnosis, demography and disability. Psychological Medicine 32:299–309, 2002Google Scholar

31. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al: Perceived need for mental health treatment in a nationally representative Canadian sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:643– 651, 2005Google Scholar

32. Codony M, Alonso J, Almansa J, et al: Perceived need for mental health care and service use among adults in Western Europe: results of the ESEMeD project. Psychiatric Services 60:1051–1058, 2009Google Scholar

33. Kamperman AM, Komproe IH, de Jong JTVM: Migrant mental health: a model for indicators of mental health and health care consumption. Health Psychology 26:96– 104, 2007Google Scholar

34. Luanaigh C, Lawlor B: Loneliness and the health of older people. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 23:1213–1221, 2008Google Scholar

35. Heinrich L, Gullone E: The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. Clinical Psychology Review 26:695–718, 2006Google Scholar

36. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Ahrens C: Age differences and similarities in the correlates of depressive symptoms. Psychology and Aging 17:116–124, 2002Google Scholar

37. Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, et al: Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging 21:140–151, 2006Google Scholar

38. Rhodes AE, Fung K: Self-reported use of mental health services versus administrative records: care to recall? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:165–175, 2004Google Scholar

39. Nutting PA, Rost K, Dickinson M, et al: Barriers to initiating depression treatment in primary care practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine 17:103–111, 2002Google Scholar

40. Gibson CH: A concept analysis of empowerment. Journal of Advanced Nursing 16:354– 361, 1991Google Scholar

41. Funnel MM, Anderson RM: Empowerment and self-management of diabetes. Clinical Diabetes 22:123–127, 2004Google Scholar

42. Arvidsson SB, Petersson A, Nilsson I, et al: A nurse-led rheumatology clinic's impact on empowering patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Nursing and Health Sciences 8:133–139, 2006Google Scholar

43. Cuijpers P: Bibliotherapy in unipolar depression: a meta-analysis. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 28:139–147, 1997Google Scholar

44. Bower P, Richards D, Lovell K: The clinical and cost-effectiveness of self-help treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in primary care: a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice 51:838–845, 2001Google Scholar

45. Den Boer PC, Wiersma D, Van den Bosch RJ: Why is self-help neglected in the treatment of emotional disorders? A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 34:959– 971, 2004Google Scholar

46. Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklicek I, et al: Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 37:319–328, 2007Google Scholar

47. Azocar F, Branstrom RB: Use of depression education materials to improve treatment compliance of primary care patients. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 33:347–353, 2006Google Scholar