Service Use for Mental Disorders and Unmet Need: Results From the Israel Survey on Mental Health Among Adolescents

The Israel Survey on Mental Health Among Adolescents (ISMEHA) is the first psychiatric epidemiological survey conducted nationwide with a representative sample of adolescents. Its purpose was to determine the prevalence of mental disorders and use of mental health services by adolescents and their parents to enable rational planning of preventive and curative services.

Studies in North America ( 1 , 2 , 3 ), Europe ( 4 , 5 ), and Australia ( 6 ) have reported that between 7% and 30% of children use some mental health services in a given year. The likelihood of a child's receipt of mental health services has been strongly linked to the presence of problem behaviors, parental perceptions of their severity, and their burden to the family ( 7 , 8 ). Sociodemographic characteristics have also been linked with use of services ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ) and with increased use among females and children of single parents, whereas service underutilization has been associated with racial-ethnic minority status ( 13 , 14 , 15 ).

Surveys on unmet needs have shown that between 60% and 85% of those needing services, as defined by the presence of a psychiatric disorder, do not seek help or do not receive help from a professional or informal source ( 16 , 17 , 18 ), and part of this treatment gap may be attributed to lack of available services ( 19 ). Unmet needs are higher for internalizing disorders, which are less burdensome for parents, than for externalizing disorders ( 20 ). However, when service use was examined among the adolescents themselves, they reported that depression and internalizing disorders, rather than externalizing disorders, were stronger indicators of need for treatment ( 20 ).

High rates of unmet needs are of great concern to all agents involved in child psychopathology, and it is crucial to understand factors promoting or discouraging help seeking in different populations ( 21 ). The ISMEHA has provided the two data sets necessary to determine unmet needs, namely prevalence of psychiatric disorders, which serves as an indicator of need for mental health services, and prevalence of service utilization. The study reported here aimed to determine the 12-month prevalence rate of service use for mental health problems; identify demographic factors, psychopathology, and learning disabilities associated with service use; and assess unmet needs.

Methods

A summary of the ISMEHA's methods is presented here. A detailed description of the sample, data collection, procedures, and instruments has been published elsewhere ( 22 ).

Sample and procedures

The sample included 957 adolescents aged 14–17 and their mothers. The sampling frame used was the National Population Register (NPR), which included the names of all legal residents of Israel born between July 2, 1987, and June 30, 1990, regardless of whether they were in school (N=317,604). Because of budgetary constraints on the study, only settlements with more than 2,000 inhabitants were included, and they constituted 90% of the target population. Only one child per family was included in the sample. Between 2004 and 2005, mothers and adolescents were interviewed separately at home by two trained lay interviewers, in Arabic, Hebrew, or Russian, as participants preferred. The interviews took 45–90 minutes.

The sample included 24 clusters, and it was extracted in two steps. To sample the settlements, the 11 largest cities were enrolled directly, and the 218 remaining ones were stratified according to type of locality (Jewish and mixed Arab-Jewish cities or mainly Arab cities) and sampled with a probability proportional to size, resulting in selection of 23 Jewish or mixed cities and ten Arab cities.

Sampling within settlements was done through the NPR. Adolescents from the largest cities were chosen proportionately to city size, and 30 adolescents from each of the smaller cities were selected via a systematic random sampling procedure. There were no replacements.

Of the total sample (N=1,402), 15% (N=207) of potential respondents could not be located, and 17% (N=238) refused to participate. Thus the response rate was 80% in the located sample (N=1,195) and 68% in the total sample. Nonresponse was higher among Jews (24%, N=218) than among Arabs (7%, N=20), whereas no significant differences by gender or immigrant status were noted. The results were weighted back to the total population to compensate for clustering effects and nonresponses.

Parents provided written informed consent for their own and their child's participation in the study, as approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the Schneider Children's Medical Center of Israel. Confidentiality was ensured.

Assessment of service utilization

Several questions assessed use of services in the 12 months preceding the interview for emotional and behavioral problems of the adolescent. Adolescents were asked about their use of school sources for advice: "In the past school year, did you consult someone in school regarding problems not connected to the learning material, such as problems with peers, at home, trouble with concentration, etc.? If yes, whom did you consult?" The list included school counselor, teacher, psychologist, friend, and school nurse, plus an option for writing in other sources. With this option, adolescents indicated their school principal and youth movement guide. Six percent (N=54) of the adolescents declared that they were not presently in school or did not answer the question asking whether they were in school and were not included in these analyses.

Mothers' use of services was assessed with the following questions: "In the past 12 months, did you think you should talk to a professional about your child's behavioral or emotional problems (or maybe drug problems)? If yes, did you talk to one of the people in the following list (family practitioner or pediatrician; other medical specialist; adolescent health clinic; psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or psychiatric nurse; school counselor; classroom or other teacher; special education teacher; other school staff; school nurse; hotline staff; self-help group; spiritual leader; alternative medicine agent; probation officer; other)?"

Diagnostic assessment of mental disorders was conducted with the Development and Well-Being Assessment Inventory (DAWBA) ( 23 ). This multi-informant interview combines structured and open-ended questions about psychiatric symptoms and their impact on the adolescent's life and on his or her family. Responses to the structured questions were used to generate a computerized diagnosis, according to DSM-IV criteria ( 24 ), clinically verified by senior child psychiatrists. The specific disorders were categorized into internalizing and externalizing disorders. Learning disability assessment was based on mothers' report of learning disability, as diagnosed by a specialist.

Sociodemographic information included gender, population group (Israel-born Jews and Jewish immigrants, or Muslim and Christian Arabs and Druze), type of locality (Jewish or mixed Jewish-Arab locality or mainly Arab locality), birthplace, maternal education (less than 12 years of schooling, 12 years of schooling with matriculation exams, or more than 12 years of schooling with some university education), maternal marital status, number of children in the family, paternal employment status, and welfare status. Data regarding gender, population group, and type of locality of residence and birthplace were based on the NPR and, therefore, are provided for the 957 respondents. The remaining sociodemographic data were provided by respondents, and thus the denominators differ slightly for each variable. Data on marital status, family size, and employment conformed to known population averages taken from reliable Central Bureau of Statistics sources.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with an SPSS-14 complex sample analysis module. Prevalence rates of adolescent and parental use of services, according to sociodemographic factors, are presented as percentages with standard errors. The tables present raw numbers and weighted percentages. The associations between service utilization and sociodemographic and clinical-diagnostic characteristics were analyzed with logistic regression analysis and presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Rao-Scott chi squares were calculated to correct for complex sample design and weighting. The adjusted F is a variant of the second-order Rao-Scott adjusted chi squares, and significance tests are based on the adjusted F and its degrees of freedom.

Results

Study population

Table 1 shows that 51% of the sample were boys, 77% were Jewish and 23% Arab or Druze, 80% lived in a Jewish or mixed Jewish-Arab locality, and 40% had a mother with a post-high school education. Fourteen percent lived with a single, divorced, or widowed parent, and more than 75% lived in families with three or more children. Twenty-three percent had fathers who were not in the workforce, and 14% of families were receiving welfare benefits.

|

Service use estimates

In the 12 months before the survey, 22% of adolescents consulted someone in school for personal or emotional problems unrelated to the school's learning curriculum. Eleven percent of the adolescents consulted, not exclusively, the school counselor, 8% their classroom teacher, 1% the school's psychologist, 1% a friend, and less than 1% the school nurse.

Among mothers, 11% perceived a need to seek help and actually consulted a professional or informal source regarding any behavioral or emotional problem of their child. An additional 2% perceived a need for treatment but did not seek care. Among the latter, two had a child with a mental disorder. Hereafter, and for clarity's sake, our analyses will not include these 17 mothers and will refer only to mothers who actually consulted someone regarding their child's behavioral or emotional problems.

Six percent of mothers consulted the school's counselor, 6% a teacher, 4% a mental health specialist, and 4% a primary care practitioner or pediatrician. The rest of the sources were each consulted by less than 1% of the mothers.

As noted elsewhere ( 25 ), 12% of adolescents in the sample had any mental disorder, 8% had an internalizing disorder, and 5% had an externalizing disorder. There were no significant differences in prevalence of mental disorders between those attending school and those who were not.

Univariate analyses

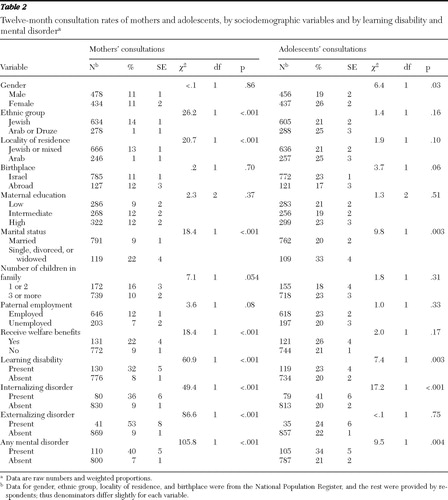

There were significantly more adolescent consultations among girls; among those living with a single, divorced, or widowed mother; and among those with a learning disability or an internalizing disorder or both ( Table 2 ). No differences in adolescents' consultations by ethnic group or locality of residence were found.

|

Maternal consultation rates varied by ethnic group and locality of residence, marital status, welfare status, and the presence of a diagnosed learning disability or mental disorder. Consultation rates were higher among Jewish mothers, mothers who were not married, those with fewer children, those receiving welfare services, and those with a child with a learning disability or an internalizing or externalizing disorder.

Multivariate analyses

We performed logistic regression analyses to determine factors associated with maternal and adolescent consultation patterns, controlling for the other variables in the model ( Table 3 ). Like their mothers, adolescents were more likely to seek help in school if they lived with a single, divorced, or widowed mother (OR=2.9) or if they had a diagnosed learning disability (OR=1.7) or an internalizing disorder (OR=2.2). In contrast with their mothers, adolescents were more likely to consult if they resided in exclusively Arab localities (OR=1.6), or if their father was employed (OR=1.7). Adolescents' gender was not found to be a differentiating factor in help-seeking practices of either mothers or adolescents. Diagnosis of an externalizing disorder was not associated with help seeking for adolescents.

|

Like their children, mothers were more likely to seek help for their child if they were not married (OR=3.1) or had a child with a learning disability (OR=4.5) or an internalizing disorder (OR=6.4). In contrast with their children, mothers were much more likely to seek help for their child if they lived in a Jewish or mixed Arab-Jewish locality (OR=18.1) or had a child with an externalizing disorder (OR=8.2).

Unmet needs

In order to determine unmet needs, we calculated how many adolescents with mental disorders or their mothers did not seek help from either professional or informal service providers. We examined unmet needs by selected sociodemographic characteristics ( Table 4 ). According to adolescents' reports, unmet needs were not significantly associated with any of the sociodemographic variables studied, except for children of divorced or single parents who presented lower rates of unmet need, whereas according to mothers' reports, among those who lived in Jewish or mixed localities 54% (CI=42.2–65.0) had unmet needs, compared with 91% among those residing in Arab localities. No significant differences were found by gender, marital status, or paternal employment.

|

In order to further understand help-seeking practices, we selected adolescents with a mental disorder (N=114) and calculated the overlap between the adolescent and the maternal reports. We found that for 12% (N=12) of these adolescents, both adolescents and their mothers consulted someone, although we do not know whether they consulted jointly or independently.

Discussion

This study explored 12-month rates for adolescent-related mental health consultations, independently reported by adolescents and their mothers, and the gap between the adolescents' needs and actual service use. Our objective was to assess help seeking from all professional and informal sources available in the community, rather than exclusively from specialized mental health services. Although this strategy allows a more complete assessment of help-seeking practices, it may lead to underestimation of unmet needs, because effective treatment may have been lacking in many of the informal consultations reported.

Service use and selected sociodemographic factors

The main findings show that 22% of adolescents and 11% of mothers sought help regarding emotional or behavioral problems of the adolescent in the 12 months preceding the survey. The results are similar to the North American, European, and Australian figures, which range from 7% to 30% ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ).

An important feature of our study is that we obtained independent reports on help-seeking practices from both adolescents and their mothers. We asked adolescents only about help seeking in school, assuming that children's and adolescents' access to mental health care is mainly dependent on parents to access the system, make appointments, transport them, and pay for services and that only when school-based services are available can children independently seek help ( 26 , 27 ). Studies have shown that exclusive reliance on parents' information may underreport school services use ( 28 ); therefore, these independent reports contributed to a more complete understanding of the role of school services as a resource.

Consultations by adolescents and their mothers were associated with distinct sociodemographic factors. Residing in an Arab locality was strongly associated with higher consultation rates in school among adolescents, whereas among their mothers, it was linked with lower consultation rates, compared with those residing in a Jewish or mixed locality. Among the adolescents internalizing disorders were associated with higher consultation rates, whereas among mothers of children with externalizing disorders the consultation rates were higher. There were common risk factors as well: we found a threefold increase in help-seeking rates among unmarried mothers as well as among their children, and diagnosed learning disability was associated with increased consultation rates among both mothers and adolescents. In contrast to studies reporting that girls use services more often than boys ( 10 , 11 ), in this study we found no gender differences in help-seeking rates of either mothers or adolescents, after controlling for the other variables in the regression model. Our finding that parents of one or two children had higher rates of consultation than parents of three or more children could be explained by the fact that parents of single children tend to be more worried and perceive the child's behavior as more problematic than parents of two or more children ( 21 ).

Service use and ethnic minority status

The literature refers to the lower-than-average use of services by minority populations in many countries. In Israel, locality of residence is strongly associated with ethnic minority status because more than 91% of Israeli Arabs reside in almost exclusively Arab localities and a small percentage live in mixed Jewish-Arab cities such as Haifa and Lod ( 29 ). Arab localities have fewer municipal resources and higher poverty rates than Jewish ones. Locality of residence and ethnic group are highly correlated in Israel and were found to be the strongest factors associated with unmet needs, which according to mothers' reports were 54% among those living in Jewish or mixed localities, compared with 91% among those in Arab localities. Attempts to explain service underutilization among the Arab minority in Israel emphasize, on the one hand, structural elements, such as referral bias or lack of access to or availability of mental health specialists or family counseling services in the Arab localities, as well as lack of Arabic-speaking mental health professionals. On the other hand, cultural elements, such as pessimistic attitudes about treatment of mental disorders ( 30 ), failure to acknowledge the problem, or reluctance to use services because of the stigma that will be attached to the adolescent and his or her family, may also play a part. Both structural and cultural elements contribute to the fact that in Israel families in ethnic minority groups seek help much less than others, even when they need help ( 15 , 17 ). Studies carried out in Arab countries also have found ambivalence and shame concerning use of mental health services to be associated with low use of services ( 31 , 32 ).

The case among minority adolescents, however, seems to be different, because we found higher school consultation rates among adolescents living in Arab localities than among those living in Jewish or mixed localities. The Arab adolescents in our sample seemed to have higher awareness of their need for help than their more conservative parents and thus sought it from accessible, Arabic-speaking school sources, made available by the Ministry of Education of Israel, which invests equally in all populations, insofar as school counseling staff is concerned. These findings are consistent with studies of rural youths in the United States that found that African-American youths were as likely as white youths to receive mental health services through schools but were only half as likely to receive care from specialty mental health settings, usually accessed through parents ( 33 ).

Use of services for subthreshold conditions

Although most studies show that the severity of psychopathology is the strongest predictor of service use ( 34 ), a great proportion of those who need care do not seek help. We found the opposite phenomenon as well, namely, that adolescents without a diagnosed disorder seek help. In our study, 21% of adolescents without a diagnosed mental disorder consulted in school, compared with 34% of those with a mental disorder. This finding could reflect a lack of statistical power to detect an association between having a disorder and use of services, but it more likely refers to a considerable proportion of children with subthreshold problems who seek help before a full-fledged problem arises ( 7 ). Among mothers, only 7% consulted someone in the absence of a psychiatric disorder, compared with 40% of those whose child had a mental disorder. Thus mothers are either more discriminating and consult only when clinical severity merits it or they are not aware of their adolescents' subthreshold mental or internalizing disorders. Another possibility is that mothers and adolescents understood differently the questions regarding "need to seek help for mental problems of the adolescent." The concept of help seeking has been found to be affected by the way a problem is defined, perception of its causes, and anticipated prognosis ( 35 ). Further research is needed to examine methodological and conceptual problems related to different interpretations of these questions.

Unmet needs

From a mental health policy perspective, the most important of the ISMEHA findings are those pertaining to unmet need for treatment: 66% and 60% according to reports of adolescents and their mothers, respectively. Although our data include consultation of informal as well as professional sources, unmet needs in our population are still higher than the 50% reported in Puerto Rico ( 36 ) and the 30% reported in a British study ( 4 ). Other studies report a wide range of unmet need, between 29% and 84% ( 37 ), but comparisons between the studies are problematic because of their different time frames and type of sources consulted.

Most studies distinguish between types of disorders for which adolescents and their mothers seek help and show that service use is higher among mothers of adolescents with externalizing disorders, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, which impose a heavy burden on parents ( 38 ) and teachers, and lower for internalizing disorders, which distress the child without resulting in much social impairment for the child or burden for others ( 20 ). Our study confirmed these findings: 53% of mothers whose child had an externalizing disorder consulted a service provider, compared with 36% whose child had an internalizing disorder. Among adolescents, however, the opposite pattern was true: 41% with an internalizing disorder consulted in school, compared with only 24% of those with an externalizing disorder.

These findings emphasize the importance of school-based mental health services, particularly for adolescents who are in a minority group and have internalizing disorders and live in Arab localities, among whom 50% consulted in school, whereas only 7% of their mothers sought help. As well, one must pay heed to studies that point to the protective effect of counseling by school sources for girls from minority groups ( 39 ). However, important questions remain regarding the actual "potential of school personnel with limited mental health expertise to respond adequately to the clinical needs of emotionally and behaviorally disturbed youth" ( 40 ).

Although it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss whether all distressed children need professional mental health care ( 41 ), it is noteworthy that some experts claim that conduct disorders should be dealt with mainly by means of parent training and school-based programs that would relieve mental health services and enable such services to focus their treatments on the minority of children whose disorders call for special mental health expertise ( 42 ). However, other experts suggest that considerable investment in this clinical population has resulted in multiple evidence-based treatments and has identified interventions that can ameliorate or effect significant change in psychiatric disorders and therefore conclude that treatment is the best choice ( 43 , 44 ).

The role of schools and primary health care

In this study, school counselors and teachers were the most frequently consulted sources by both adolescents and their mothers. This finding strengthens the common knowledge that schools are an ideal and opportunistic setting to identify and refer children and adolescents with mental problems or, if specialized staff is present, to provide mental health care ( 26 ). The relatively high rates of use of school-based services point to the need for the implementation of strategies to include specialized mental health professionals and school counselors in every school and to upgrade the counseling expertise and identification and referral skills of teachers and school nurses. Less than 1% of adolescents consulted the school nurse, although 77% reported that there was a nurse in their school. It is clear that the role of the school nurse, vis-à-vis the emotional and behavioral concerns of adolescents and their families, should be revised.

The primary health care system, which functions in Israel in the framework of universal national health insurance, is underutilized as a source of consultation for emotional and behavioral problems of adolescents, as shown by the fact that only 4% of mothers consulted a primary care physician, who in other studies has been identified as important in the pathway to care ( 28 ). Although the potential role of primary health providers with regard to the mental health care of adolescents should be examined more carefully, it is possible that general practitioners need skills and training and updating of their job description in order to include routine screening for mental disorders among children and adolescents.

As in other countries ( 45 ), in Israel there seems to be a lack of clarity regarding the role and responsibility of each of the agencies involved in provision of mental health care for children and adolescents and the ways these agencies could complement each other. To meet the multiple and complex mental health, social, and educational needs of young people, strong interagency partnerships must be formed ( 41 ).

Limitations

A potential limitation of this study is the possibility of selection bias. For example, the level of mental health service use would be underestimated if mothers who suspected that their adolescent child had a mental health problem or who consulted someone for their own or their child's mental health problems were less likely than other mothers to participate in the survey.

Another limitation is that we did not collect data on actual differences in quality, availability, and accessibility of mental health services for the different population groups. Therefore, conclusions regarding the relative weight of structural or cultural factors on the use of services cannot be offered.

Conclusions

Overall, our results suggest that adolescents and their mothers have different consultation rates and patterns and that the majority did not seek help in the 12 months before the interview even in the presence of mental health care needs. Compared with their mothers, more adolescents with internalizing disorders consulted school sources. Among adolescents with externalizing disorders, more mothers consulted a professional or informal service provider. The large gap in help seeking between Jewish and Arab mothers who have a child with a mental disorder requires a better understanding of the underlying structural and cultural factors that undermine use of services in the Arab Israeli population.

Several tasks confront the adolescent mental health policy makers and specialists working with different population groups. The main one is the strengthening the skills of school counselors and training of other school staff who serve as the most common consultation sources. Collaboration schemes among the educational establishment, primary health care, and mental health services should be developed to improve access to mental health care. As well, there is a need to develop infrastructure, plan culturally appropriate services, and increase and promote professional training of Arabic-speaking mental health professionals in order to provide the needed services for the Arab population. Finally, government measures to remedy the effects of poverty on large segments of the child and adolescent population should be a national priority as a first mental health preventive measure.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This survey was supported by the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research, the Association for Planning and Development of Services for Children and Youth at Risk and Their Families (ASHALIM), the Englander Center for Children and Youth of the Brookdale Institute, and the Rotter Foundation of the Maccabi Health Services, Israel. Dr. Ponizovsky was supported in part by the Ministry of Immigrant Absorption of Israel. The authors also acknowledge the important contribution of Robert Goodman, Ph.D., F.R.C.Psych., to the completion of this project; of Jane Costello, Ph.D., in the planning of this project; of Rasim Kanaaneh, M.D., for his diagnostic assessment; of Olga Goraly, M.D., in the Russian translation; and of Anneke Ifrah, M.A., M.P.H., and Anat Shemesh, M.A., M.P.H., in the preparation of this article.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Costello EJ, Famer EMZ, Angold A: Psychiatric disorders among American Indian and white youth in Appalachia: the Great Smoky Mountains Study. American Journal of Public Health 87:827–832, 1997Google Scholar

2. Simpson GA, Cohen RA, Pastor PN, et al: Use of Mental Health Services in the Past 12 Months by Children Aged 4–17: United States, 2005–2006. NCHS Data Brief 8. Atlanta, Ga, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Sept 2008. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db08.htm Google Scholar

3. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al: Mental health service use in a nationally representative Canadian survey. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:753–761, 2005Google Scholar

4. Meltzer H, Gatward R, Corbin T, et al: Persistence, Onset, Risk Factors and Outcomes of Childhood Mental Disorders. London, Office for National Statistics, 2003Google Scholar

5. Heiervang E, Stormark KM, Lundervold AJ, et al: Psychiatric disorders in Norwegian 8- to 10-year-olds: an epidemiological survey of prevalence, risk factors, and service use. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 46:438–447, 2007Google Scholar

6. Sawyer M, Arney P, Baghust J, et al: The mental health of young people in Australia: key findings from the child and adolescent component of the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 35:806–814, 2001Google Scholar

7. Ford T, Hamilton H, Goodman R, et al: Service contacts among the children participating in the British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Surveys. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 10:2–9, 2005Google Scholar

8. Teagle SE: Parental problem recognition and child mental health service use. Mental Health Services Research 4:257–266, 2002Google Scholar

9. Tick NT, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC: Ten-year increase in service use in the Dutch population. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 17:373–380, 2008Google Scholar

10. Kahan-Strawczynski P, Konstantinov V, Yurovich L: Adolescent Girls in Israel: An Analysis of Data From Selected Studies. RR no 485-06. Jerusalem, Israel, Engelberg Center for Children and Youth, 2006Google Scholar

11. Tishby O, Turel M, Gumpel O, et al: Help-seeking attitudes among Israeli adolescents. Adolescence 36:249–264, 2001Google Scholar

12. Zimmerman FJ: Social and economic determinants of disparities in professional help-seeking for child mental health problems: evidence from a national sample. Health Services Research 40:1514–1533, 2005Google Scholar

13. Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB: Unmet need for mental health care among US children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1548–1555, 2002Google Scholar

14. Wu P, Hoven CW, Cohen P, et al: Factors associated with use of mental health services for depression by children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services 52:189–195, 2001Google Scholar

15. Al Krenawi A: Mental health service utilization among the Arabs in Israel. Social Work in Health Care 35:577–589, 2002Google Scholar

16. Zachrisson HD, Rödje K, Mykletun A: Utilization of health services in relation to mental health problems in adolescents: a population based survey. BMC Public Health 6:34, 2006Google Scholar

17. Naon D, Morginstin, B, Schimmel M, et al: Children With Special Needs: An Assessment of Needs and Coverage by Services. RR-355-00. Jerusalem, Israel, Brookdale Institute, Center for Research on Disabilities and Special Populations, 2002Google Scholar

18. Costello EJ, Copeland W, Cowell A, et al: Service costs of caring for adolescents with mental illness in a rural community, 1993–2000. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:36–42, 2007Google Scholar

19. Levav I, Jacobsson L, Tsiantis J, et al: Psychiatric services and training for children and adolescents in Europe: results of a country survey. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 13:395–401, 2004Google Scholar

20. Wu P, Hoven CW, Bird HR, et al: Depressive and disruptive disorders and mental health service utilization in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1081–1090, 1999Google Scholar

21. Verhulst FC, van der Ende J: Factors associated with child mental health service use in the community. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:901–909, 1997Google Scholar

22. Mansbach-Kleinfeld I, Levinson D, Farbstein I, et al: Israel Survey of Mental Health Among Adolescents: Aims, Methods, Strengths and Limitations. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, in pressGoogle Scholar

23. Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, et al: The Development and Well-Being Assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 41:645–655, 2000Google Scholar

24. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

25. Farbstein I, Mansbach-Kleinfeld I, Levinson D, et al: Prevalence and Correlates of Mental Disorders in Adolescents: Findings from the Israel Survey on Mental Health Among Adolescents (ISMEHA). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry Epub ahead of print, Oct 27, 2009Google Scholar

26. Rickwood DJ, Deane FP, Wilson CJ: When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Medical Journal of Australia 187:35–39, 2007Google Scholar

27. Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A: 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. methods and public health burden. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44:972–986, 2005Google Scholar

28. Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, Phillips SD, et al: Pathways into and through mental health services for children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services 54:60–66, 2004Google Scholar

29. Manna A (ed): Arab Society in Israel: Population, Society, Economy. Jerusalem, Israel, Van Leer Jerusalem Institute/Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 2008Google Scholar

30. Ponizovsky AM, Geraisy N, Shoshan E, et al:Treatment lag on the way to the mental health clinic among Arab- and Jewish-Israeli patients. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences 44:234–243, 2007Google Scholar

31. Eapen V, Ghubash R: Help-seeking for mental health problems of children: preferences and attitudes in the United Arab Emirates. Psychological Reports 94:663–667, 2004Google Scholar

32. Youssef J, Deane FP: Factors influencing mental health help seeking in Arabic communities in Sydney, Australia. Mental Health, Culture and Religion 9:43–66, 2006.Google Scholar

33. Angold A, Erkanly A, Famer EMZ, et al: Psychiatric disorder, impairment and service use in rural African American and white youth. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:893–901, 2002Google Scholar

34. Ford T, Hamilton H, Meltzer H, et al: Predictors of service use for mental health problems among British schoolchildren. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 13:32–40, 2008Google Scholar

35. Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Riedel-Heller SG: Whom to ask for help in case of a mental disorder? Preferences of the lay public. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:202–210,1999Google Scholar

36. Canino G, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipec M, et al: The DSM-IV rates of child and adolescent disorders in Puerto Rico: prevalence, correlates, service use, and the effects of impairment. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:85–93, 2004Google Scholar

37. Ford R, Hamilton H, Meltzer H, et al: Child mental health is everybody's business: the prevalence of contact with public sector services by type of disorder among British school children in a three-year period. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 12:13–20, 2007Google Scholar

38. Sayal K, Goodman R, Ford T: Barriers to the identification of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 47:744–750, 2006Google Scholar

39. Borowsky IW, Ireland M, Resnick MD:Adolescent suicide attempts: risks and protectors. Pediatrics 107:485–493, 2001Google Scholar

40. Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, et al: Children's mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs 14(3):147–159, 1995Google Scholar

41. Vostanis P: Mental health of looked after children. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 9:256–257, 2003Google Scholar

42. Goodman R: Child mental health: an overextended remit. British Medical Journal 314:813–814, 1997Google Scholar

43. Kazdin AE: Evidence-based treatment and practice: new opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. American Psychologist 63:146–159, 2008Google Scholar

44. Lochman JE, Wells KC: The Coping Power program at the middle-school transition: universal and indicated prevention effects. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 16:S40–S54, 2002Google Scholar

45. Goodman R: Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services: Reasoned Advice to Commissioners and Providers. Maudsley Discussion Papers no 4. London, King's College, Institute of Psychiatry, 1997Google Scholar