Pathways to Inpatient Mental Health Care Among People With Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders in South Africa

Mental health care systems in low- and middle-income countries are underresourced ( 1 , 2 ). In order to maximize the available resources, it is important to understand service utilization patterns, particularly the manner in which service users gain access to care in these countries. Service utilization data, such as pathways to care, delays in treatment, and access to specialist services, are seldom gathered routinely and yet are vital for service planning ( 3 , 4 ).

Service access and use are important issues in the province of the Western Cape in South Africa, which has been undergoing deinstitutionalization since the mid-1990s, in keeping with international trends ( 5 , 6 ). In 1995 there were 61 beds per 100,000 population in psychiatric hospitals in the province, excluding beds for people with intellectual disabilities ( 7 ). By 2000 this ratio had fallen to 49 beds per 100,000, and by 2005 it had decreased further to 39 per 100,000, a total reduction of 36% in ten years ( 8 ). However, as in many other countries, the reduction of bed numbers in psychiatric institutions has not been accompanied by the development of adequate community mental health services ( 8 , 9 ). Recent data indicate high rates of relapse and a "revolving door" pattern of care, described as repeated readmissions following brief periods in the community, particularly among people with severe mental illness ( 10 ). Patterns of service utilization in the Western Cape have also been influenced by an escalating demand for services because of the impact of HIV-AIDS and methamphetamine dependence ( 11 , 12 ). Reforms in the legislative environment—through the Mental Health Care Act (2002)—require that mental health services should be integrated into primary and secondary care and that patients should use tertiary care (psychiatric hospitalization) as a last resort.

Studies from high-income countries have demonstrated marked differences in service utilization patterns among high- and low-frequency service users ( 13 ). In the context of deinstitutionalization in low- and middle-income countries, it is important to track service needs and access to care among high-frequency service users to assess the ability of community services to support people with a high need for mental health services outside of hospital settings. Little is known about the differences in service utilization between high- and low-frequency service users in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in Africa.

The purpose of this study was to report on service utilization patterns and pathways to specialist mental health services among individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in the Western Cape, South Africa. A secondary purpose was to examine the differences between high- and low-frequency service users in this context.

Methods

Setting

The study took place at the three psychiatric hospitals in the Western Cape Province of South Africa: Lentegeur, Stikland, and Valkenberg Hospitals. Each caters to a catchment area containing approximately 1,500,000 people ( 14 ). Each catchment area consists of two regions, one in the Cape Town metropolis and one in a contiguous rural region. Public-sector mental health services in the urban areas are provided at community mental health clinics situated in community mental health centers (primary care), district (general) hospitals (secondary care), and the three psychiatric hospitals mentioned above (tertiary care). Each community mental health clinic is staffed by a professional nurse four days per week and by a psychiatric registrar (resident physician) three hours per week. When possible, patients with stable conditions are discharged from the mental health clinic and receive the required mental health services in general community health services, located in clinics and community health centers. In these resource-limited clinics, regular follow-up of patients who default from treatment is often not possible, and long waiting times are common. Patients requiring admission to a psychiatric hospital typically present first to a community mental health clinic. Thereafter, they are referred either to a district hospital for medical assessment and a 72-hour observation in accordance with the Mental Health Care Act (2002) or directly to the psychiatric hospital if they have recently been discharged from such a hospital. Behaviorally disturbed patients in the community are often brought to the psychiatric hospital by police services. Although the policy guidelines detail the steps that persons can use to receive mental health services, the guidelines do not provide for those who require intensive community support. In addition to these service constraints, the Cape Town urban population is generally marked by economic deprivation, with high levels of poverty, crime, and violence ( 15 ).

Sample

Individuals who were consecutively admitted to any of the three psychiatric hospitals in the Western Cape from February 2007 to January 2008 were interviewed. In order to be included in the study, participants had to be aged 18 to 59 years; have a current diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or schizoaffective disorder; require treatment with antipsychotic medication in the opinion of the investigators; and be able to give written, informed consent to participate. Exclusion criteria were the presence of moderate or severe intellectual disability, admission because of a severe medical illness other than a psychiatric diagnosis, and a finding that the patient did not expect to reside in the Cape Town metropolis in the following year.

Procedure

Data were gathered from service users, their relatives or associates, and hospital files. All service users and other informants were interviewed by using a semistructured interview to establish the following: demographic information; personal, medical, and family history; psychiatric history, including number of relapses; initial and current diagnosis; age of onset of psychosis; history of previous admissions and treatment; current treatment; treatment adherence and reasons for a lack thereof; and any comorbid medical conditions. Data collected from the hospital files were largely of a clinical nature. Concordance between respondents and hospital files was not formally evaluated, but there was a reasonable level of concordance. Where there was discordance between the self-report and file information, the respondent report was taken as the more accurate for personal or demographic data, and the file was taken as the best source for clinical data. In addition, questionnaires eliciting data on substance abuse and pathways to care were administered. The box on the next page shows the questions used to determine the pathways to care.

Questions used to determine the pathways to care for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in the Western Cape, South Africa

All settings

What was the duration of the index episode of untreated psychosis until first contact with

Health services?

Mental health services?

First admission?

First treatment with antipsychotic medication?

Who initiated the help seeking for the current episode?

What prompted help seeking?

Did the user consult a nonmedical practitioner (such as a traditional or faith healer) before admission?

Primary care services

Was the user seen at this level?

Did the user receive treatment at this level?

What was the nature of the treatment?

Was the user admitted to a district hospital, and if so, for how long? a

Was there a delay of more than 24 hours in referral from the primary care level to the next level of care?

Secondary care services

Was the user seen at this level?

Was the user admitted to a hospital facility at this level?

Tertiary care services

Did the user bypass lower levels of care?

Who was the referring agent?

What was the main reason for referral?

Did admission occur during office hours?

Were the police involved in bringing the user to the hospital?

Was the user accompanied by a caregiver?

Was there a bed available?

How was the user classified on admission?

Was the hospital informed of the pending admission before arrival?

Did the user have a referral letter?

How long had it been since the user's previous admission (in days)?

Was the user discharged as an emergency discharge on the last admission?

a District hospitals are the first point of inpatient hospital admission within the primary care system.

Any of the above information that could not be gathered as a result of the user's mental state at admission was gathered at a later stage during the hospital admission, up to the date of discharge. All participants were classified as high- or low-frequency users of psychiatric services according to a modified version of the revolving-door criteria of Weiden and Glazer ( 13 ). Although the Weiden and Glazer criteria require admission resulting from exacerbation of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and at least one previous admission in the past 12 months or two previous admissions in the past three years, our criteria were somewhat more strict in terms of the frequency of previous admissions. Our criteria included any of the following: first, three or more admissions in the past 18 months or five or more in the past 36 months; second, two or more admissions in the past 12 months and treated with clozapine; and third, two or more admissions in the past 12 months and 120 days in the hospital or longer. These criteria were used per recommendations from clinicians from all three psychiatric hospitals because, compared with countries where community services are relatively well developed, in South Africa patients have poor support in the community and are more likely to be admitted to a hospital.

Analysis

All data were entered into a database. The two groups (high- and low-frequency users) were compared in relation to the above listed putative risk factors. Categorical variables were compared by using chi square analysis or Fisher's exact test. In multivariate analysis, the model was adjusted for gender, ethnic group, marital status, education, residential area, and main source of income. Continuous variables were compared using Student's t tests. Correlations between continuous variables were calculated using Spearman's rank order correlation coefficients. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a significance level of .05 was used throughout.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference of Harmonisation's Good Clinical Practice guidelines ( 16 ) and the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written, informed consent before discharge. If users were unable to give consent because of illness, data were still gathered and consent sought from users when possible. If the user did not give consent by the time of discharge, study information for that user was not entered into the database and was deleted. When possible, a caregiver or associate of the user also signed the informed consent as a witness. To ensure confidentiality each patient was allocated a study number, which was the only identifying information entered into the database. Patient identifiers, linked to the study participant number, were kept in a separate, password-protected file that could be deleted once data processing was completed. The study was approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of Cape Town and the Faculty of Health Sciences Committee for Human Research at Stellenbosch University.

Results

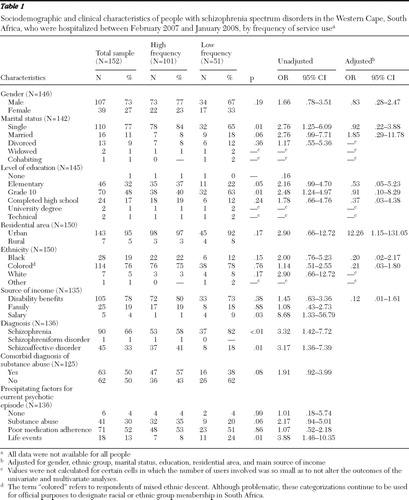

The sample consisted of 101 high-frequency users and 51 low-frequency users (N=152) ( Table 1 ). The mean± SD age for the sample was 35.03± 10.10 years. High-frequency users were significantly younger than low-frequency users (33.57±10.00 years versus 37.80±9.77 years) (p=.02). High-frequency users were significantly more likely to be single, but this association was no longer significant in the multivariate analysis. The mean monthly income of the sample was R766±388 (approximately $79 in the United States), and high-frequency users had significantly lower income than low-frequency users (R715±340 versus R872±460) (p=.03). High-frequency users also tended to rely more on disability benefits for their income, although this difference was not statistically significant. High-frequency users were more than eight times less likely to earn a salary. Low-frequency users were almost four times more likely to have experienced a life event as a precipitating factor in their admission. High-frequency users were significantly more likely to have a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and low-frequency users were significantly more likely to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

|

The majority of service users in the sample were seen at the primary care level before admission to a psychiatric hospital (N=84, 62%). (All data were not available for all people.) However, only 35 (26%) received any form of treatment there, with the most common treatment being anxiolytics (N=20, 14%). Very few received antipsychotic medication at the primary care level. A similar trend was noted at the district and regional hospital level (secondary care level), where 38 patients (28%) were seen, but only 29 (21%) were admitted. Of the total sample, 30 (22%) were admitted directly to the psychiatric hospital, bypassing other treatment options. Low-frequency users were more likely to be seen at the primary care level (N=33, 73%), whereas high-frequency users were more likely to bypass other levels of care and go to the psychiatric hospital directly (N=26, 29%) (p=.009).

More than 48 (36%) admissions occurred after hours, the most likely cause of which was delays at the primary care level (N=20, 43%). The vast majority of patients (N=123, 90%) were involuntarily admitted. Police were involved in 69 (51%) admissions. Poor medication adherence was the most likely precipitant for the episode of illness, followed by substance abuse (in the case of high-frequency users) and life events (in the case of low-frequency users).

There were a number of important differences between high- and low-frequency users in access to and delays in treatment ( Table 2 ). High-frequency users were admitted sooner after their first symptoms. Although high-frequency users tended to live further away from the hospital in which they received care, they tended to get to help sooner—that is, delays in treatment were shorter. High-frequency users were more likely to have been classified as an "emergency discharge" at their last admission. Emergency discharge occurs when the patient has residual symptoms and is not well enough to be discharged in the opinion of the clinician but is discharged because of the needs for limited beds and because he or she is less unwell than service users waiting to be admitted.

|

Discussion

The study highlights the inadequacy of the current system of primary mental health care in providing for the needs of service users, particularly high-frequency users, in Western Cape, South Africa. Although the majority of patients were seen at the primary care level, very few received appropriate treatment at this level. Thus although services at the primary care level are accessible, they are clearly not equipped to be the main source of mental health care for people with severe mental illness. This finding points to crucial training needs among primary care staff and the importance of developing resources and capacity for mental health care at this level. The findings also underscore the need to strengthen community mental health services, including assertive community treatment (ACT) teams, particularly for high-frequency users.

Several patients were seen at the district or regional hospital level and not admitted. This is striking in light of the provisions of the Mental Health Care Act (2002), which requires that unless a patient has been recently discharged, he or she should be admitted for 72 hours of observation before referral to psychiatric hospitals. It is clear from these findings that the provisions of the act are not being implemented, either because staff do not have the skills or capacity to admit patients or because facilities are not available. Routine information systems to monitor these trends need to be strengthened.

The study also points to important differences between high- and low-frequency service users in access to treatment and delays in seeking such treatment. These findings are consistent with other studies, which have found that predictors of high-frequency service use include more previous admissions, longer length of stay, and a diagnosis of schizophrenia ( 17 , 18 ). In this study reasons for the more direct access to psychiatric hospitals by high-frequency users include the possibility that this group of users was known to both caregivers and service providers as having more severe symptoms and that caregivers or service users who are familiar with services could gain access to tertiary care more readily. There is agreement among service providers that users who have been discharged more recently may be referred directly to psychiatric hospitals and are not required to enter care at the primary care level. A more formal designation of what constitutes a high-frequency user may therefore be desirable to improve access to the appropriate level of care. Given the evidence of increased substance abuse among high-frequency users in this study, there is a need for interventions that target substance abuse in community service settings.

Internationally, the findings of this study indicate important differences between (and within) African countries in pathways to care ( 19 , 20 ). In the Western Cape province there are relatively well-resourced public-sector mental health services, compared with other provinces in South Africa and other African countries ( 2 , 8 , 21 ). However, the preponderance of psychiatric hospitals as a locus of care in the Western Cape leads to a tendency for service users to be referred directly to these facilities, particularly when services are not available at the primary or secondary levels.

The high level of police involvement and the high proportion of involuntary admissions also indicate the need for training among the police regarding the provisions of the Mental Health Care Act and working with persons with mental illness.

The leading role of poor medication adherence in precipitating illness episodes for both high- and low-frequency users may indicate the potential benefits of community mental health services, such as ACT, in monitoring and supporting service users in the community and preventing relapse. ACT teams have been found to be particularly effective in meeting the needs of high-frequency users in other countries, reducing length of hospital stay by up to 50% according to one meta-analysis ( 22 ). In the Western Cape, early evaluations of the newly established ACT program show a reduction in inpatient admissions and length of stay, as well as improved user, family, and staff satisfaction ( 23 ).

There are several limitations to the study. First, the small sample means that any conclusions drawn from the study should be interpreted with caution. Second, some of the exclusion criteria (such as being a resident outside the Cape Town metropolis) may have biased the sample characteristics and access to services. Third, the survey was conducted with service users who were admitted to a psychiatric hospital. The findings regarding service utilization patterns therefore cannot be generalized to those who have not been admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Fourth, the retrospective nature of some of the data implies that they may have been subject to recall bias. This bias was minimized by using multiple sources of data.

Conclusions

Although the majority of service users in this study received health care services at the primary care level, very few of them received adequate mental health care at this level and tended to find mental health care at the specialist level. The study highlights the inadequacy of current community mental health services in providing for the needs of people with severe mental illness. This study also shows important differences between high- and low-frequency users, namely that high-frequency users were younger, had lower income, tended to rely more on disability benefits, and were more likely to bypass other levels of care and be admitted directly to a psychiatric hospital.

In South Africa, as in many other middle-income countries, there is an urgent need to develop community-based care. In the case of the Western Cape province these services are needed to supplement a relatively well-established psychiatric hospital infrastructure. This finding is consistent with previous South African mental health services research ( 8 , 9 ). It is also consistent with challenges facing middle-income countries that have been identified by the World Health Organization, namely the need to provide community care facilities, integrate mental health into primary health care, and ensure availability of essential psychotropic drugs in all health care settings ( 6 ).

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study forms part of a wider assertive community treatment research program, funded by the Provincial Government of the Western Cape Health Department. Dr. Lund was funded by the Department for International Development, as part of the Mental Health and Poverty Project. The director of the Associated Psychiatric Hospitals, Linda Hering, M.B.Ch.B., has been instrumental in supporting this initiative. The authors are grateful to Martin Kidd, Ph.D., for his assistance with the statistical analysis. The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the funders.

Dr. Stein has received research grants or consultation honoraria from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Orion, Pfizer, Pharmacia, Roche, Servier, Solvay, Sumitomo, Takeda, Tikvah, and Wyeth. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, et al: Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity and inefficiency. Lancet 370:878–889, 2007Google Scholar

2. Atlas: Mental Health Resources in the World. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005Google Scholar

3. Gater R, De Almeida E, Sousa B, et al: The pathways to psychiatric care: a cross-cultural study. Psychological Medicine 21:761–774, 1991Google Scholar

4. Mental Health Information Systems: Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005Google Scholar

5. Geller JL: The last half-century of psychiatric services as reflected in Psychiatric Services. Psychiatric Services 51:41–67, 2000Google Scholar

6. World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2001Google Scholar

7. Ensink K, Leger PH, Robertson BA: Mental health services in the Western Cape. South African Medical Journal 87:1183–1210, 1997Google Scholar

8. Lund C, Kleintjes S, Kakuma R, et al: Public sector mental health systems in South Africa: inter-provincial comparisons and policy implications. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, Epub ahead of print, Jun 9, 2009Google Scholar

9. Lund C, Flisher AJ: Community/hospital indicators in South African public sector mental health services. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 6:181–187, 2003Google Scholar

10. Temmingh H, Oosthuizen P: Pathways to care and treatment delays in first and multi episode psychosis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43:727–735, 2008Google Scholar

11. The Western Cape Antiretroviral Programme: Monitoring Report, 2006/7. Cape Town, South Africa, Provincial Government of the Western Cape, Department of Health, 2007Google Scholar

12. Pluddemann A, Myers BJ, Parry CD: Surge in treatment admissions related to methamphetamine use in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for public health. Drug and Alcohol Review 27:185–189, 2008Google Scholar

13. Weiden P, Glazer W: Assessment and treatment selection for "revolving door" inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly 68:377–392, 1997Google Scholar

14. Statistics South Africa. Census 2001. Pretoria, Statistics South Africa, 2001. Available at www.statssa.gov.za/census01/HTML/default.asp Google Scholar

15. Ndegwa D, Horner D, Esau F: The links between migration, poverty and health: evidence from Khayelitsha and Mitchell's Plain. Social Indicators Research 81:223–234, 2007Google Scholar

16. Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R1). Geneva, International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, 1996. Available at www.ich.org/cache/compo/276-254-1.html Google Scholar

17. Fisher S, Stevens RF: Subgroups of frequent users of an inpatient mental health program at a community hospital in Canada. Psychiatric Services 50:244–247, 1999Google Scholar

18. Korkeila JA, Lehtinen V, Tuori T, et al: Frequently hospitalised psychiatric patients: a study of predictive factors. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:528–534, 1998Google Scholar

19. Abiodun OA: Pathways to mental health care in Nigeria. Psychiatric Services 46:823–825, 1995Google Scholar

20. Bekele YY, Flisher AJ, Alem A, et al: Pathways to psychiatric care in Ethiopia. Psychological Medicine 39:475–483, 2009Google Scholar

21. Flisher AJ, Lund C, Funk M, et al: Mental health policy development and implementation in four African countries. Journal of Health Psychology 12:505–516, 2007Google Scholar

22. Bond GR, McGrew JH, Fekete DM: Assertive outreach for frequent users of psychiatric hospitals: a meta-analysis. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:4–16, 1995Google Scholar

23. Botha U, Koen L, Oosthuizen P, et al: Assertive community treatment in the South African context. African Journal of Psychiatry 11:272–275, 2008Google Scholar