A Comparison of the Life Goals Program and Treatment as Usual for Individuals With Bipolar Disorder

Although many patients with bipolar disorder have been helped by the rapid expansion of pharmacopoeia for the treatment of bipolar disorder ( 1 ), treatment effectiveness remains suboptimal. Rates of treatment nonadherence are variable, but they are generally substantial and in the order of 12% to 64% ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ). Although mood stabilizers are the cornerstone of treatment for bipolar disorder, previous studies have demonstrated that psychotherapies, including psychoeducational interventions specific to bipolar disorder, may enhance pharmacotherapy and improve clinical outcome ( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). It has been suggested that various psychoeducational interventions from briefer stepped-care packages ( 10 , 11 ) to more comprehensive group packages ( 6 ) also can aid in treatment adherence. However, effects of psychosocial approaches, including psychoeducation, on treatment adherence are not consistent, and there is a need to identify core components of psychosocial interventions that most affect treatment adherence because of the resource limitations found in many clinical settings ( 12 ).

The Life Goals Program (LGP) is a manual-driven structured group psychotherapy program for individuals with bipolar disorder ( 13 ). LGP is focused on systematic education and individualized application of problem solving in the context of mental disorder to promote illness self-management ( 13 ). It has been demonstrated that patients with bipolar disorder participating in LGP may significantly improve their knowledge about bipolar disorder ( 13 ), and the LGP developers have suggested that medication adherence could be improved with LGP ( 13 ). Interestingly, clinical characteristics usually associated with poor outcome, such as substance abuse, have not been reported to correlate with diminished LGP participation or success. Moreover, collaborative chronic care management models that have been adapted for bipolar disorder and that include LGP have shown significant improvements in clinical outcome ( 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ), function ( 15 ), and quality of life ( 15 ) in long-term, multisite, randomized controlled trials.

Previously published trials have used LGP within the context of a combined care approach ( 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ), and there are no published data on how LGP may specifically affect treatment adherence in populations of persons with bipolar disorder. A randomized controlled, multicomponent intervention study (that included LGP among the multiple components) conducted in a managed care setting did not specifically evaluate medication adherence ( 16 ). A randomized, controlled collaborative care model (CCM) study by the Department of Veterans Affairs that included LGP as one of the multiple components and evaluated medication adherence as a secondary outcome did not find a difference between the CCM group and the control group ( 17 ), but because the CCM study had several components it was not possible to separate effects of LGP from those of other activities, such as nurse care management ( 14 , 15 ). To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous studies using a controlled methodology that tested LGP as a stand-alone intervention.

This randomized controlled study examined 164 outpatients with bipolar disorder in a community mental health center who were randomly assigned to standardized psychoeducation (LGP) or treatment as usual to see whether there were differences between the groups in treatment adherence attitudes and behaviors. We anticipated that patients who received LGP would demonstrate improvement in treatment adherence attitudes as well as improvement in bipolar symptoms and functional status.

Methods

This project was a randomized, controlled study that determined the effects on treatment adherence attitudes and behaviors when a standardized psychoeducational intervention (LGP) was added to treatment as usual among outpatients with bipolar disorder treated at a community mental health center. Patients who qualified for study entry were randomly assigned to treatment as usual or to treatment as usual plus LGP and were assessed at baseline and then at the three-, six-, and 12-month follow-ups.

Study population

Eligible study participants had type I or type II bipolar disorder as confirmed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Inventory ( 18 ). In order to obtain a real-world generalizable sample of patients with bipolar disorder, we established minimal exclusion criteria (inability to provide informed consent and inability to be rated on psychiatric rating scales), similar to prior randomized controlled trials of collaborative care management models ( 14 , 17 ). The study was approved by the local institutional review board. Study participants were recruited through clinician referrals, or they were self-referred in response to posted advertisements. The study was conducted from July 11, 2002, to June 6, 2007.

LGP

LGP is based on behavioral principles from social learning and self-regulation theories that underlie a collaborative practice model ( 13 ). LGP is supported by explicit manuals; uses a preset script, topic focus, and topic sequence; and was delivered by research staff trained in its use by the program developers and study principal investigators (MS and MAD). LGP is organized in two phases—phase I and II, which cover illness education, management, and problem solving. Phase I of LGP, which was the core psychoeducational intervention in this study, was delivered as six weekly, interactive group sessions. The content and format of the psychoeducational groups have been described in detail elsewhere ( 13 , 19 ). Group size was generally six to eight members. After completion of the six weekly psychoeducational sessions, participants were encouraged to attend optional phase II monthly group sessions that addressed goal setting and problem solving in an unstructured format as described by Bauer and McBride ( 13 ).

Adherence issues are specifically targeted in phase I of LGP ( 13 ). In session 3 the therapist helps members to recognize the role of medication nonadherence (and other ineffective coping behaviors) in perpetuating the "high" of mania or in triggering a manic episode. In session 5 the therapist helps members to consider adherence to medication as an adaptive coping response to the signs and symptoms of depression and triggers of depressive episodes. Finally, in session 6 the therapist addresses individualized adherence issues when assisting patients with their personal care plan.

The LGP intervention was administered by the study co-principal investigator (MAD), a doctorate-level registered nurse, and a psychiatric counselor (master's level) supervised by the study co-principal investigator. In addition to use of the LGP treatment manual ( 13 ), LGP training consisted of a one-day intensive onsite training and ongoing telephone support by the developers of LGP. Fidelity to the intervention was assessed by a co-principal investigator who attended the first six months of the psychiatric counselor-led LGP sessions. The co-principal investigator (MAD) then delivered feedback on key LGP format and content issues at the end of each session. LGP was administered in addition to treatment as usual. Staff working for the study investigators made reminder telephone calls to LGP participants before the weekly group sessions. Individuals who were not reachable through telephone were sent reminder letters. Because LGP was delivered in a group format, the LGP sessions did not always occur on the same days that individuals had their regular treatment-as-usual appointments. Staff of the community mental health center were generally very supportive and welcoming with respect to the LGP process, and they offered the use of a "group room" at the community mental health center for staff working for study investigators to hold the LGP sessions.

Treatment as usual

Treatment-as-usual services for patients with bipolar disorder at the community mental health center typically include medication management by a psychiatrist, psychosocial therapy and counseling by mental health clinicians (Ph.D. psychologists, mental health nurses, or psychiatric social workers), and access to social services or case management for individuals who require more intensive assistance. Data were not collected on specific treatment-as-usual services for study participants.

Measures

Sociodemographic and clinical information. Sociodemographic and clinical information, including age, gender, education, occupation, social class ( 20 ), ethnicity, age of onset of illness, and psychiatric comorbidity, were collected from participants and confirmed by medical record. Self-reported history of sexual and physical abuse was also collected because of its reported relationship to treatment adherence among adults with serious mental illness ( 21 ).

Treatment adherence. Adherence attitudes were measured by the ten-item Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI). Although not a direct measure of adherence behavior, the DAI has been demonstrated to be associated with degree of adherence with psychotropic medication among individuals with serious mental illness ( 22 ), and it is known to be relatively unaffected by psychiatric symptom severity ( 23 ). The DAI is a simple, true-false format questionnaire that assesses domains of patients' attitudes, including positive and negative experience, locus of control, and attitudes toward medication. Possible scores range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating better attitudes toward medication. Responses are scored on a euphoric-dysphoric continuum ( α =.93), with higher scores corresponding to the euphoric end of the spectrum.

Treatment adherence behaviors were evaluated by self-reported treatment adherence behaviors (SRTAB) within the past 30 days, similar to self-reported adherence methods reported in other trials with persons with bipolar disorder ( 24 ). Only psychotropic medications were assessed for adherence, and individuals were asked to provide an estimate (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, or 100%) that was closest to their average adherence with all prescribed psychotropics combined. Participants were informed that their information was confidential and would not be shared with treatment providers, with the exception of circumstances in which the individual was an acute risk of harm to self or others.

Symptoms, global psychopathology, functional status, and substance abuse. Symptoms were measured with the 24-Item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) ( 25 , 26 ) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) ( 27 ). Functional impairments caused by illness were assessed with the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) ( 28 ). Substance abuse comorbidity was assessed as a continuous measure using a portion of a standardized instrument, the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) ( 29 ).

Possible scores on the HAM-D range from 0 to 74, with higher scores indicating more severe depression. Possible scores on the YMRS range from 0 to 44, with higher scores indicating more severe mania. Possible scores on the GAS range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher functional status. Possible scores on the ASI range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more severe substance abuse.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis of the data was performed with standard univariate techniques available in SPSS software. Categorical data were compared with chi square analysis or Fisher's exact test. Continuous data were compared with Student's t test. Because this was a first study of LGP as a stand-alone intervention, sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the effect of the intervention with respect to completer analyses, last observation carried forward, and outcome by LGP participation intensity, as well as with respect to patient-specific variables (age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, social class, suicide history, substance abuse history, history of abuse, psychosis, depression and mania severity, functional status, and past hospitalizations). Mixed-model repeated-measures analysis was used to test for differences in DAI scores between the three subgroups with different levels of LPG attendance (no sessions, one to three sessions, or four to six sessions) and the treatment-as-usual group, after the analysis adjusted for covariates. SAS PROC MIXED software was used to assess the model that included subgroups (the three subgroups with different levels of LPG attendance) and the treatment-as-usual group and time as fixed effects; baseline HAM-D, YMRS, and GAS scores as covariates; and DAI scores as the repeated measure. Study participants were treated as random components in the model. A compound symmetry variance-covariance matrix was used to express the correlational structure of the repeated DAI measurements. The influence of the covariates on DAI scores was determined by the significance, magnitude, and sign of the appropriate estimated coefficient of the covariate.

Results

Baseline status

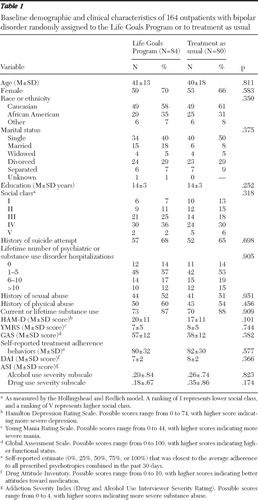

Initially, 166 individuals met study entry criteria. Two were not enrolled because of subsequently identified study exclusion criteria; therefore, 164 individuals were enrolled in the study. Eighty-four individuals were randomly assigned to LGP plus treatment as usual and 80 individuals were randomly assigned to treatment as usual. Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups. The two groups were closely matched at baseline, and there were no significant differences between the groups in demographic or clinical variables.

|

Baseline scores on DAI and SRTAB were also similar between the two groups. The sample had good representation of participants from racial and ethnic minority groups (over 40%) and a preponderance of female participants (nearly 70%). The group overall demonstrated moderately severe depressive symptoms (mean±SD HAM-D score=18.6±11.3), minimal to moderate manic symptoms (mean YMRS score=7.4±5.4), and impaired functioning (mean GAS score=57.4±12.2). In the total sample, 52 (32%) had current mania or hypomania, and 50 (30%) had current psychotic symptoms. Comorbid substance abuse, either current or lifetime, was seen in 87% (N=143) of the total sample, and 2% (N=3) of the sample had at least moderately severe levels of current substance abuse, as evaluated by the ASI. The study did not deliberately focus on individuals with known nonadherence, and baseline attitudes toward medication were moderately good (mean DAI score=7.4±2.3). On average, study participants reported that they took 81% of their prescribed bipolar medication treatments.

Study outcomes

Study participation. Overall, 128 participants—63 (75%) in the group assigned to LGP plus treatment as usual and 65 (81%) in the treatment-as-usual group—participated in baseline assessment and at least one follow-up rating. Among participants in the group assigned to LGP plus treatment as usual, slightly less than half (N=41, 49%) participated in most or all (four to six sessions) of the phase I LGP sessions, another 14% (N=12) participated in one to three of the sessions, and 37% (N=31) never participated in the group sessions. After completion of the core LGP phase I psychoeducation, fewer than 10% (N=8) of participants chose to attend the phase II unstructured groups.

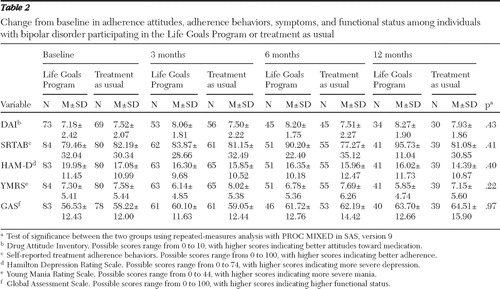

Adherence attitudes and other outcome measure. There was no significant difference in DAI scores over time between the group assigned to LGP plus treatment as usual and the treatment-as-usual group. Similarly, there were no significant differences between the groups in SRTAB, symptom measures, psychopathology, or functional status at any of the follow-up points. Selected outcomes of the two groups are presented in Table 2 . Although there was a significant temporal pattern of improvements in adherence attitudes and behaviors, symptoms, and functional status of all patients over time, there was not a statistically significant difference between the groups.

|

Exploratory analyses

Given the high rates of nonparticipation in LGP, we conducted a secondary analysis of the change in DAI score from baseline by comparing three subgroups with different levels of LPG attendance (no sessions, one to three sessions, or four to six sessions) and the treatment-as-usual group. As indicated in Figure 1 , individuals with partial and full participation appeared to have improved attitudes toward medication at both the three- and six-month follow-ups; however, by the one-year follow-up, there was no difference in scores between the three LGP subgroups. Effect sizes at three months were .07 for persons attending no LGP sessions, .16 for persons attending one to three sessions, and .59 for persons attending four to six sessions. At six months, effect sizes were .35, .35, and .49, respectively ( Figure 1 ).

An emerging body of literature suggests that some psychosocial treatments are not as effective among individuals who are more ill or who have had more past mood episodes ( 28 ). We thus assessed whether individuals with more symptoms, psychosis, substance abuse, lower functional status, or more previous hospitalizations for psychiatric or substance abuse indications had differences in outcome in LGP plus treatment as usual versus treatment as usual. A mixed-model repeated-measures analysis for tests of fixed effects ( Table 3 ) found that there was a trend (p=.056) for higher levels of depressive severity at baseline (as measured by the HAM-D) to predict more negative attitudes toward bipolar medications over time (as measured by DAI), and more time in any treatment predicted more positive attitudes toward bipolar medications over time (as measured by DAI); other variables were not significant.

|

As noted in the Methods section, additional analyses were conducted to evaluate the effect of the intervention with respect to completer analyses, last observation carried forward, and patient-specific variables. When we compared persons in the LGP group who did not go to any sessions and those who participated in some sessions, those who did not go to any sessions were younger (mean age 37.2±8.4 years versus 44.5±11.2 years, p=.004) and had less education (mean years of education 12.5±2.3 years versus 14.0±2.7 years, p=.010). Other demographic and clinic factors were not significantly different.

Finally, we conducted an additional secondary analysis that excluded individuals who self-reported very high rates of treatment adherence (over 75%) at baseline to evaluate whether LGP had effects among individuals who were known to be nonadherent or partially adherent at baseline. There was no treatment effect in this subsample (only a treatment-by-time interaction). However, it must be noted that a relatively small number of participants met this criterion and had enough complete data to conduct an analysis.

Discussion

This was the first randomized controlled trial of LGP plus treatment as usual versus treatment as usual. The study was conducted with 164 adults with bipolar disorder receiving care in a community mental health center and found that all patients improved over the one-year study duration. Although study results did not show a statistically significant difference between treatment groups at the 12-month follow-up, it must be emphasized that fewer than half of patients randomly assigned to LGP actually participated fully in the intervention. Relatively low rates of study participation and similarly low rates of LGP attendance underscore the difficulties in conducting controlled trials with individuals with bipolar disorder in community mental health center settings. Despite these limitations, secondary analyses give some indication that LGP plus treatment as usual had an effect in the expected direction (more positive attitudes toward medication treatment); however, this effect appeared to disappear over time in the absence of structured and ongoing intervention. Although most individuals self-reported taking approximately 80% of prescribed bipolar medication treatments at baseline, DAI scores suggested that individuals had mixed attitudes toward medications. Additionally, individuals with depressive symptoms that were more severe at baseline trended to have lower DAI scores (indicating poorer attitudes toward medication) at the end of the study.

The suboptimal participation in LGP sessions in our study contrasts sharply with the approximately 80% of participants who attended 75% or more of LGP sessions in the two prior effectiveness trials of collaborative care models that included the LGP intervention ( 14 , 15 , 16 ). It may be that these patients differed systematically in some way from the patients in our study: the study by Bauer and colleagues ( 14 , 15 ) involved veterans and the study by Simon and colleagues ( 16 ) involved members of a managed care health organization (HMO). The Department of Veterans Affairs care setting and culture may facilitate higher participation and retention rates in clinical trials, whereas managed care populations are often healthier and less impaired. As might be expected from a public-sector care population, this group of individuals with bipolar disorder was quite ill at baseline, with relatively low functioning. Approximately 75% of our sample had a history of suicide attempts, with an average of one to five previous hospitalizations for mental disorders or substance abuse. It is possible that attitudes toward medication (and perhaps psychosocial therapies) in this sample might have been shaped by the experience of rather severe ongoing symptoms, as well as by a history of extensive family and personal trauma. It has been suggested that individuals with more severe symptoms or a longer duration of illness may respond less well to psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder, compared with individuals with illness of more recent onset or those who are euthymic ( 6 , 30 ). Alternatively, there may be factors related to receiving care for bipolar disorder in a community mental health center that impede treatment, that are not found in the Department of Veterans Affairs ( 14 , 15 ) or in staff model HMOs ( 16 ).

The most notable difference between other trials ( 14 , 15 , 16 ) and the study presented here is that LGP was a stand-alone treatment in our study, whereas in other trials it was part of an integrated care management package. Nonetheless, there appeared to be a progressive increase in effect size with LGP "dose," indicating either that sufficient participation in LGP, even without an integrated care model, can achieve the desired effect or that participants who participate adequately in the intervention are the ones who will have the greatest benefit.

Challenges to participation in our study often centered on group time scheduling, transportation problems getting to the clinic, and competing life demands, such as work or child care. A number of individuals did not own a car and relied on public transportation, which was not always readily available during the times the group sessions were scheduled, despite the fact that group leaders tried to optimize the timing of group sessions for participants. An additional impediment to the implementation of psychoeducation in some cases was the group process itself. Although LGP groups can be supportive and motivating for some individuals with bipolar disorder ( 30 ), in other instances, variations within the group, such as the presence of individuals with psychotic symptoms, can be disruptive. The heterogeneity within LGP groups, such as differences in cultural and educational background or health literacy could contribute to isolation of some group members. De Andrés and colleagues ( 31 ) conducted an uncontrolled prospective study of LGP taught in a group format, noting that individuals participating in LGP had improvements in depressive symptoms and self-reported stabilization of mood. As with the study presented here, the study by De Andrés and colleagues ( 31 ) had better participant retention in phase I (80%) and comparatively lower participation in phase II (38%). However, without a comparison group it is difficult to assess whether symptom improvement was simply related to improvement that might have occurred in the course of usual clinical care or was a unique effect of LGP.

Simple feasibility issues such as scheduling can make the LGP group format more difficult, thus attenuating in a real-world application any benefit that may accrue from the mutual learning, support, and destigmatization that are benefits of the group format ( 13 ). Accordingly, LGP has been reformatted and manualized as an individual treatment option to facilitate dissemination to those who cannot or will not participate in groups ( 32 ). Alternative methods to work around scheduling and transportation problems include the use of telephone-based LGP, as has been used by some groups of investigators ( 33 , 34 ).

Findings and recommendations based on study results should be interpreted while acknowledging that the study sample included mainly patients with depressive symptoms and was drawn entirely from a community mental health center. Although depression is the predominant mood state among individuals with bipolar disorder and the community mental health center represents a typical real-world setting in which many bipolar patients receive care, findings may not be generalizable to populations with bipolar disorder symptoms of mania or those receiving treatment in other mental health care settings. Also, the sample was predominantly female. It is possible that the nature of a group psychotherapy intervention is more acceptable to women than men. An uncontrolled study of LGP among individuals with bipolar disorder conducted in Switzerland similarly enrolled a preponderance of female patients ( 31 ). Additional limitations include the fact that reliance on self-report may underestimate treatment adherence, there were no direct quantitative measures of fidelity to the LGP intervention, study raters were not blinded to treatment assignment, and data were not collected on number of visits or types of services in treatment as usual for study participants—there may have been differences between study groups in the treatment as usual. Finally, LGP in this study was a stand-alone intervention. Integration of LGP with other interventions, such as nurse-delivered case management, as part of a package of care might have led to more robust improvements in attitudes toward medication treatment ( 14 , 15 ).

Conclusions

Outcomes related to patients' drug treatment attitudes were not significantly different at the 12-month follow-up between patients who received LGP plus treatment as usual and those who received treatment as usual. Effects of the short-term LGP intervention may become lost over time without some form of ongoing intervention that addresses drug treatment attitudes. Depressed individuals with bipolar disorder may have reduced response to LGP. Logistic problems for patients with bipolar disorder who receive care within a community mental health center may limit the applicability of group-format psychoeducation. Finally, an intervention specifically focused on treatment adherence or LGP combined with other types of interventions might be needed to effectuate attitudinal change in the long term.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Career Development Award K23-MH-065599-01A (Dr. Sajatovic), by grant P20-MH-066054-01 (Dr. Calabrese, Dr. Davies, Dr. Ganocy, and Mr. Hays) from the NIMH, and by the Woodruff Foundation (Dr. Sajatovic and Dr. Davies).

Dr. Sajatovic has received research grants from GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca, and she has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, the Cognition Group, and United BioSource Corporation. Dr. Calabrese has served on advisory boards for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Forest Laboratories, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Organon, Ortho-McNeil, Repligen Corporation, Servier Pharmaceuticals, Solvay and Wyeth, and Supernus Pharmaceuticals. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Goldberg JF: Treatment guidelines: current and future management of bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:12–18, 2000Google Scholar

2. Gitlin M, Cochran S, Jamison K: Maintenance lithium treatment: side effects and compliance. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 44:127–131, 1989Google Scholar

3. Lee S, Wing YK, Wong KC: Knowledge and compliance towards lithium therapy among Chinese psychiatric patients in Hong Kong. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 26:444–448, 1992Google Scholar

4. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al: Factors associated with pharmacologic noncompliance in patients with mania. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:292–297, 1996Google Scholar

5. Weiss RD, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, et al: Medication compliance among patients with bipolar disorder and substance use disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59:172–174, 1998Google Scholar

6. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, et al: A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:402–407, 2003Google Scholar

7. Craighead WE, Microwatts DJ: Psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder. Clinical Psychiatry 61:58–64, 2000Google Scholar

8. Huxley NA, Parikh SV, Baldessarini RJ: Effectiveness of psychoeducational treatments in bipolar disorder: state of the evidence. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 8:126–140, 2000Google Scholar

9. Sajatovic M, Chen PJ, Dines P, et al: Psychoeducational approaches to medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 15:181–192, 2007Google Scholar

10. Cochran SD: Preventing medical noncompliance in outpatient treatment of bipolar disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 52:873–878, 1984Google Scholar

11. Scott J, Tacci MJ: A pilot study of concordance therapy for individuals with bipolar disorders who are non-adherent with lithium prophylaxis. Bipolar Disorders 4:386–392, 2002Google Scholar

12. Sajatovic M, Chen PJ, Dines P, et al: Psychoeducational approaches to medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. Disease Management and Health Outcome 15:181–192, 2007Google Scholar

13. Bauer MS, McBride L: The Life Goals Program: Structured Group Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder. New York, Springer, 2003Google Scholar

14. Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al: Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: part I. intervention and implementation in a randomized effectiveness trial. Psychiatric Services 57:927–936, 2006Google Scholar

15. Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al: Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: part II. impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs. Psychiatric Services 57:937–945, 2006Google Scholar

16. Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Bauer MS, et al: Long-term effectiveness and cost of a systematic care management program for bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:500–508, 2006Google Scholar

17. Sajatovic M, Biswas K, Kilbourne A, et al: Factors associated with prospective long-term treatment adherence among individuals with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 59:753–759, 2008Google Scholar

18. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(suppl 20):22–33, 1998Google Scholar

19. Bauer MS, Williford WO, Dawson EE, et al: Principles of effectiveness trials and their implications in VA Cooperative Study #430: "reducing the efficacy-effectiveness gap in bipolar disorder." Journal of Affective Disorders 67:61–78, 2001Google Scholar

20. Mollica RF, Milic M: Social class and psychiatric practice: a revision of the Hollingshead and Redlich model. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:12–17, 1986Google Scholar

21. Lecomte T, Spidel A, Leclerc C, et al: Predictors and profiles of treatment non-adherence and engagement in services problems in early psychosis. Schizophrenia Research 102:295–302, 2008Google Scholar

22. Awad AG: Subjective response to neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 19:609–618, 1993Google Scholar

23. Sajatovic M, Rosch DS, Sivec HJ, et al: Insight into illness and attitudes toward medications among inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 53:1319–1321, 2002Google Scholar

24. Sajatovic M, Bauer MS, Kilbourne AM, et al: Self-reported medication treatment adherence among veterans with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 57:56–62, 2006Google Scholar

25. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 23:56–62, 1960Google Scholar

26. Williams JB: Standardizing the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: past, present and future. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 251(suppl 2):II6–II12, 2001Google Scholar

27. Young RC, Briggs JT, Ziegler VE: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity, and sensitivity. British Journal of Psychiatry 133:429–435, 1978Google Scholar

28. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766–771, 1976Google Scholar

29. McLellan AT, Luborsky LL, Woody GE: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26–33, 1980Google Scholar

30. Scott J, Paykel E, Morris R, et al: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for severe and recurrent bipolar disorders-randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 188:313–320, 2006Google Scholar

31. De Andrés RD, Aillon N, Bardiot MC, et al: Impact of the life goals group therapy program for bipolar patients: an open study. Journal of Affective Disorders 93:253–257, 2006Google Scholar

32. Bauer MS, Ludman E, Greenwald DE, et al: Overcoming Bipolar Disorder: A Comprehensive Workbook for Managing Your Symptoms and Achieving Your Life Goals. Oakland, Calif, New Harbinger, 2009Google Scholar

33. Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Nossek A, et al: Service delivery in older patients with bipolar disorder: a review and development of a medical care model. Bipolar Disorders 10:672–683, 2008Google Scholar

34. Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Nossek A, et al: Improving medical and psychiatric outcomes among individuals with bipolar disorder: a randomized, controlled trial. Psychiatric Services 59:760–768, 2008Google Scholar